Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

For nearly two decades, the F-35 Lightning II was sold to NATO as more than just a fighter jet. It was a symbol of unity, interoperability, and American technological dominance—a warplane so advanced that to refuse it was to invite obsolescence.

But that illusion is cracking.

In March, Portugal became the first NATO country to cancel its F-35 order outright, citing instability in U.S. foreign policy and growing doubts about Washington’s long-term reliability. Within 24 hours, Canada followed suit—not with a cancellation, but with something more dangerous to Lockheed Martin: a full-spectrum contract review of its $19 billion commitment, publicly confirmed by Prime Minister Mark Carney on April 15.

That wasn’t a trial balloon. That was a declaration of strategic uncertainty.

The timing couldn’t be worse for the United States. President Donald Trump has escalated tariffs on Canada and the European Union, threatened to cripple NATO, and openly floated the idea of annexing Canada as a path to eliminate trade friction. European leaders, meanwhile, are accelerating their “Buy European” defense initiative, and pushing for a procurement realignment that could leave U.S. contractors—and influence—in the cold.

This isn’t a policy adjustment. This is the beginning of a continental shift.

The age of guaranteed American dominance in NATO air power is over. The only question now is what replaces it—and how fast.

Let’s break it down.

Sometimes geopolitical ruptures don’t come with fanfare—they come with a press release, a shrug, and a phone call no one wants to answer. That’s what happened when Portugal backed out of the F-35 program.

The move was surgical, intentional, and grounded in the cold math of strategic self-preservation. On March 12, Lisbon quietly informed NATO partners that it was cancelling its planned F-35 acquisition, citing three clear reasons:

Hours later, the situation escalated.

On March 13, Canadian Defence Minister Bill Blair went public in an interview with CBC, confirming that Canada was “actively reassessing” its 88-jet commitment. He referenced the first 16 planes—already paid for and in production—but emphasized that the remainder of the order was “under full strategic review.” He cited value-for-money concerns, national sovereignty, and alternative European platforms as key variables.

Then things moved fast.

The message is clear: this is no longer hypothetical. The F-35’s dominance in NATO procurement is being challenged—methodically, publicly, and from both sides of the Atlantic.

And the pace is accelerating.

What began as a procurement contract has evolved into a geopolitical referendum.

When Prime Minister Mark Carney confirmed on April 15 that Canada’s Department of National Defence had formally launched a review of the F-35 program, it didn’t just shake up Lockheed Martin’s stock price—it signaled the most serious reconsideration of U.S. defense reliance in Canadian history.

Let’s be clear: Canada isn’t canceling the program (yet). The first 16 jets are still inbound. But the remaining 72—the lion’s share of the $19 billion deal—are up for negotiation, restructuring, or even redirection. And Ottawa is already talking to other suppliers.

Carney, still in caretaker mode following his recent swearing-in, made one thing obvious: this review isn’t about “delays” or “technical tweaks.” It’s about national sovereignty and economic autonomy. Speaking from Dorval, Quebec, he declared that Canada was committed to “getting value for money” and maximizing domestic economic participation in any future defense deal.

That’s a direct rebuke of the F-35’s limitations: no local assembly, no tech transfer, and tightly controlled software access governed from the Pentagon.

Enter Saab.

Now that matters.

Why? Because if Canada goes with Saab, it won’t just be buying jets—it will be rebuilding its own aerospace industrial base, which was gutted during decades of outsourcing to U.S. suppliers.

And Carney knows it. He’s already hinted that Canadian companies could become part of a new transatlantic supply chain through EU procurement pacts—something only possible if Canada pivots away from an all-F-35 fleet.

France’s Dassault Rafale is also circling. Paris has already offered Rafales to Portugal as a post-F-35 alternative, and Macron has privately pitched the aircraft to Carney. While pricier than the Gripen, the Rafale offers nuclear capability, combat-proven versatility, and no software kill switches—a growing concern among NATO buyers.

This is no longer a question of procurement logistics. It’s a question of whether Canada defines itself as a sovereign actor in defense—or remains tethered to a fragile alliance led by a volatile United States.

And so far, the Carney government is acting like it wants options.

If Canada is cautiously reconsidering its F-35 future, Europe is already halfway out the door.

Over the last six weeks, the European Union has accelerated what it long hinted at: a strategic divorce from U.S.-led defense procurement. The trigger wasn’t just Trump’s tariff salvos or his threats to pull funding from NATO. It was a deeper realization—one that Macron has articulated with increasing bluntness: the transatlantic defense relationship is no longer reliable.

And for once, he’s not alone.

In a press conference with Carney on March 17, Macron argued that Europe must “control the tools of its own security.” Days later, the European Commission unveiled a €150 billion defense procurement pact, encouraging member states to prioritize interoperable European platforms and consolidate manufacturing within EU borders.

This is the same policy playbook the U.S. has used for decades—but now, Brussels is running it in reverse.

France’s Dassault Rafale is the tip of this spear. Combat-proven and NATO-compatible, the Rafale has already seen exports to India, Egypt, Greece, and Indonesia. But its biggest opportunity might be inside Europe itself—as the alternative to the F-35.

Portugal has reportedly entered informal talks with Dassault to fill the capability gap left by its F-35 cancellation. Spain and Belgium—both wrestling with political backlash over U.S. weapons dependency—are watching closely.

Macron’s pitch is straightforward:

And it’s landing.

Germany is in the most conflicted position of all.

A procurement pivot from Berlin would carry more weight than Lisbon or Ottawa combined. And it’s not unthinkable.

Europe’s not just shifting away from the F-35—it’s drawing a blueprint for a post-American defense architecture.

And with U.S. instability rising, more countries may decide it’s time to follow the plan.

For decades, the U.S. didn’t have to sell the F-35—it just had to offer it. The promise of stealth dominance, NATO interoperability, and exclusive access to next-gen tech made it irresistible.

But now, as allies back away, Washington is reaching for the only tools it has left: pressure, punishment, and narrative warfare.

Trump’s preferred weapon isn’t subtle—it’s economic. Since returning to office, he’s levied new tariffs on Canadian and European aerospace components, targeting sectors that coincidentally overlap with F-35 production and its rival platforms.

If Canada or any EU state fully exits the F-35 pipeline, expect this pressure to intensify. Washington won’t say it’s retaliation. But it won’t have to.

The more potent threat may not come from Trump—it may come from Lockheed Martin and the Pentagon.

The F-35 isn’t just a jet. It’s a software-defined platform controlled through encrypted systems that require U.S. approval for updates, diagnostics, and mission programming.

Allied nations don’t own the code. They rent access to it.

If a country starts scaling back or tries to pivot away from the F-35 mid-program, the U.S. has a range of options:

In effect, Washington can make it painfully difficult for a halfway-out nation to continue operating the jets it already owns.

Expect the U.S. State Department and NATO command to lean hard on one central message: F-35 interoperability is non-negotiable.

The script will be familiar:

“If you’re not flying F-35s, you’re not truly integrated. You’re putting your pilots—and the alliance—at risk.”

It’s not just about jets. It’s about who gets a seat at the table during real-time mission planning. Countries operating outside the F-35 ecosystem may find themselves politically isolated within NATO command structures.

That’s the subtext: Buy American, or stay in the kiddie pool.

The message is clear: leaving the F-35 program comes at a cost. And Washington intends to make that cost unmistakably painful.

But for many allies, the question is no longer if there will be consequences—it’s whether they’re finally willing to pay them.

The F-35 program has always been a paradox: the most expensive weapons system in history, sold on the promise that the more countries bought in, the cheaper it would become.

That logic worked—until it didn’t.

Now, with Portugal gone, Canada reevaluating, and Germany hedging, the financial equation behind the F-35 is looking dangerously brittle. The entire program is built on economies of scale. If NATO partners start dropping out, that foundation cracks—and Lockheed Martin’s cost model begins to collapse under its own weight.

At its core, the F-35 is a shared risk investment. Each NATO buyer helps spread the cost of:

If just one major buyer reduces its order—let alone cancels—it doesn’t just shrink Lockheed’s revenue; it raises the per-unit cost for every remaining country.

Portugal’s exit was small but symbolic. If Canada scales back, it’s financial. If Germany or Spain follows, it’s existential.

Recent internal forecasts (unpublished but leaked via industry analysts) suggest:

This is the nightmare scenario: a cost death spiral where every buyer’s departure accelerates the collapse of the pricing model.

Lockheed Martin can:

None of these are sustainable.

The F-35 program was built on mass adoption. Now, as nations exit or stall, that mass is evaporating—and with it, the jet’s economic viability.

In the arms race of 21st century geopolitics, the F-35’s greatest threat may not be Chinese stealth or European competition. It may be its own shrinking coalition of buyers.

The F-35 isn’t just facing criticism—it’s facing competitors. Real ones.

As NATO’s faith in the American-built stealth fighter wanes, two European warplanes are stepping into the vacuum with increasing legitimacy: Sweden’s Saab Gripen E and France’s Dassault Rafale.

Neither has the stealth profile of the F-35. But both offer something the F-35 can’t: freedom. Freedom from U.S. software control. Freedom from remote diagnostics and hidden override code. Freedom from a defense ecosystem that punishes deviation with economic pain.

And that freedom is suddenly very attractive.

Dassault’s Rafale is the elder statesman of Europe’s air platforms—but it’s not aging out. It’s aging into a new geopolitical moment.

With nuclear-capable variants, multirole agility, and a combat-proven track record from Mali to Syria, the Rafale brings immediate credibility to any country looking to pivot away from U.S. control without sacrificing performance.

Macron is using it as a soft-power tool, personally pitching it to Portugal, Spain, and even Carney’s Canada. The message?

“Buy from Paris, not from a country that just threatened to annex you.”

In diplomatic terms, that’s a hell of a sales pitch.

Saab’s Gripen E is leaner, cheaper, and arguably more relevant for mid-tier NATO allies. Designed for rugged environments, short runways, and modular upgrades, it’s tailor-made for Arctic powers like Canada or nations with limited infrastructure.

But the real killer app? Technology transfer and local assembly.

Sweden’s deal with Canada included:

For countries like Canada or Portugal, that’s not just appealing—it’s strategic. It means rebuilding domestic aerospace capacity while breaking Lockheed’s monopoly.

The F-35 may still be the stealthiest jet on the planet, but right now? Gripen and Rafale are the fastest-moving.

And in the geopolitical race to escape U.S. defense control, speed might matter more than stealth.

The F-35’s moment of reckoning isn’t a distant theoretical—it’s unfolding in real time. Allies are moving. Markets are reacting. Washington is posturing. Europe is organizing.

Now the question becomes: what happens next?

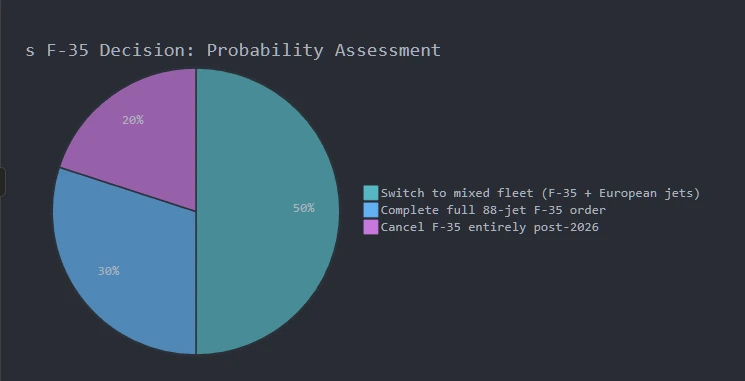

At Prime Rogue Inc., we assess geopolitical defense transitions not just by sentiment, but by scenario mapping. Based on current declarations, procurement data, and alliance dynamics, here’s what the next 6–12 months are likely to look like across NATO:

Probability: 50%

Canada adopts a mixed fleet. Germany delays future F-35 commitments. Spain exits the discussion entirely. The result is a fragmented NATO air posture—with some flying U.S. stealth, others flying French or Swedish jets, and command interoperability suffering as a result.

Interoperability breaks down. F-35 loses its monopoly. NATO cohesion weakens.

Probability: 30%

The U.S. applies enough pressure to keep allies in line, offering limited concessions like spare part guarantees or training offsets. Canada keeps all 88 jets, but at the cost of domestic political backlash. EU allies stall but don’t defect.

F-35 survives intact—but resentment simmers under the surface.

Probability: 20%

Trump escalates dramatically: harsher tariffs, threats to exit NATO, tech blackmail. In response, key allies accelerate European alignment. Canada cancels remaining F-35 orders. EU launches legal framework for a Buy European Pact. Lockheed begins to scale back production forecasts.

A new European defense bloc forms in open defiance of U.S. arms control.

One defection can be explained. Two raise eyebrows. But three or more within 12 months? That’s not drift.

That’s a breakaway.

The F-35 was supposed to be the unifying symbol of NATO’s next-generation air power—a marvel of stealth and software binding U.S. allies into one interoperable network. For a time, it was.

But in 2025, that consensus is gone.

Portugal has already walked. Canada is halfway out the door. Germany and Spain are looking for exits. The European Union is crafting new procurement doctrine. And Washington, instead of recalibrating, is doubling down on pressure, punishment, and loyalty tests.

This isn’t a story about fighter jets. It’s a story about who controls the future of Western defense.

And increasingly, it looks like NATO will fracture into two camps:

For Canada, the F-35 review isn’t just a procurement audit—it’s a geopolitical litmus test. Does Ottawa continue outsourcing defense to an increasingly erratic ally? Or does it hedge, diversify, and rebuild capacity at home?

The decision will echo across Europe, the Arctic, and NATO itself.

The skies are still filled with F-35s—for now.

But in the silence behind the afterburners, you can hear the machinery of realignment starting to hum.