Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

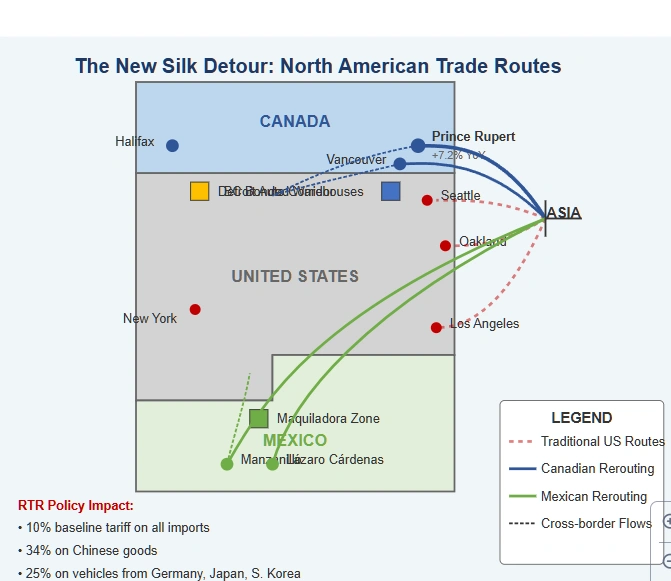

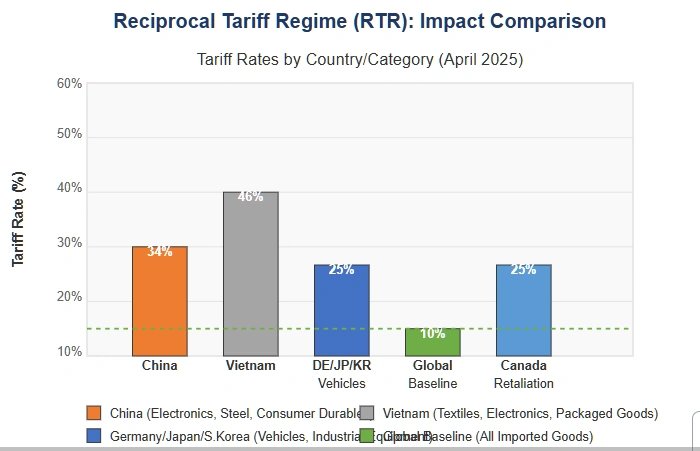

On April 2, 2025, President Donald J. Trump announced a sweeping new trade policy branded as “Liberation Day”, launching the Reciprocal Tariff Regime (RTR). The directive imposes a 10% baseline tariff on all imported goods entering the United States, with escalated rates targeting countries with large trade surpluses. That includes a 34% tariff on Chinese goods, a 46% tariff on Vietnamese exports, and 25% blanket tariffs on vehicle and industrial equipment imports from Germany, Japan, and South Korea. The policy went into effect in two stages: April 5 (baseline tariffs) and April 9 (targeted surcharges).

In response, Canada announced a 25% retaliatory tariff on U.S.-made vehicles that fail to comply with the USMCA’s North American content rules. That measure also came into force on April 9, 2025, and is expected to affect over $35 billion CAD in U.S. exports, particularly in the automotive corridor spanning the upper Midwest.

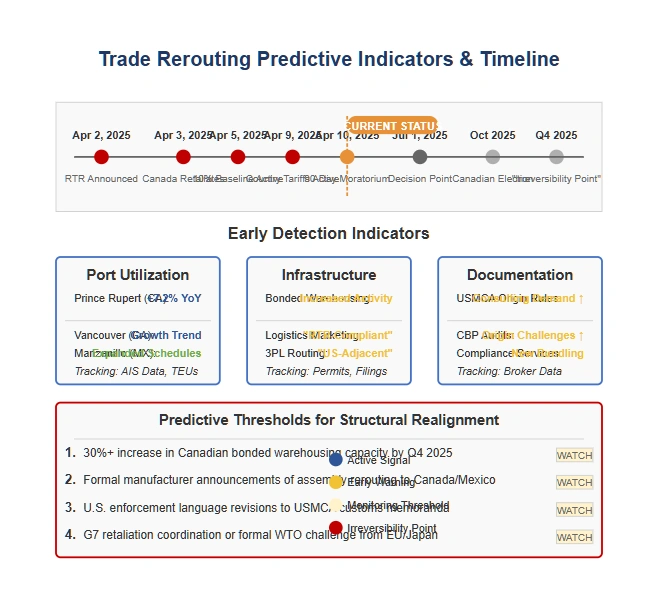

This is no longer a bilateral dispute or a standard trade war. It is a structural break — the de-integration of the U.S.-led trade architecture, triggered by a combination of executive discretion, policy volatility, and retaliatory pressure. There is no dispute resolution mechanism in use. There are no active WTO channels. What began as a unilateral escalation now signals something deeper: systemic withdrawal of trust from U.S.-centric trade infrastructure. After a stock market bloodbath, Trump has imposed a 90 day moratorium on his own tariffs except for those imposed on Canada, Mexico, and China.

As of this writing, there is no confirmed mass shift in shipping routes or declared supply chain realignments by major multinational firms. However, a pattern of early-stage repositioning is now detectable:

This intelligence brief does not claim a rerouting revolution is underway. It states that the conditions now exist for that process to begin in earnest — and that the next 90 days will determine whether the U.S. remains a gateway or becomes a choke point.

The world does not need to abandon American markets.

It only needs to avoid depending on American ports.

And it’s already started to plan for that.

On April 2, 2025, President Trump announced the Reciprocal Tariff Regime (RTR) as a unilateral overhaul of U.S. trade policy. Presented during a nationally televised speech dubbed “Liberation Day”, the policy was framed as the “rebalancing of decades of economic subjugation.” The program introduced two tiers of enforcement:

Key components of RTR include:

The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) confirmed that no WTO consultations were initiated, and that the tariff regime would remain in place “indefinitely, until trade parity is restored.” No clear metrics for defining “parity” were published.

The policy rollout occurred on a compressed timeline:

The immediate international response included formal statements of concern from:

However, the most substantial response came from Canada. On April 3, Prime Minister Mark Carney announced a 25% retaliatory tariff on all U.S.-made vehicles failing USMCA origin rules, effective April 9. The measure applies to approximately $35.6 billion CAD in affected imports and is legally justified under Article 232 of the Canadian Customs Tariff Act. Unlike previous trade spats, Canada did not pursue WTO arbitration or bilateral negotiations. The retaliatory measure was presented as defensive and indefinite.

As of April 10, there are no confirmed retaliatory tariffs from the European Union, Japan, or Vietnam. However, official channels in each case have signaled that reciprocal reviews are underway.

If RTR remains in effect beyond June 30, 2025, without exemptions or bilateral accommodations:

This event does not mark the start of a trade war. It marks the end of the presumption that the U.S. is operating under multilateral constraint based on the Trump Doctrine. The shift is not tactical. It is doctrinal.

Prior to April 2025, the dominant supply chain response to U.S. trade volatility was redundancy. Multinationals built parallel facilities, secured alternate sourcing contracts, and maintained contingency shipping plans — not to abandon the U.S. market, but to buffer against periodic policy disruptions.

This strategy was most visible between 2018 and 2020, during the first round of U.S. tariffs under Section 301. Manufacturers shifted some production from China to Vietnam or Thailand, and others rerouted sensitive goods through South Korea or Taiwan. The changes were significant, but largely temporary, because trade enforcement itself remained rule-bound and reversible.

That assumption no longer holds.

The Reciprocal Tariff Regime (RTR) introduced on April 2, 2025, is not linked to a legislative process, not embedded in a multilateral framework, and not subject to scheduled review. The unpredictability of enforcement — both in terms of criteria and escalation — introduces what logistics planners describe as a systemic incoherence premium: the cost of designing around a node that may enforce retroactively, arbitrarily, or at executive whim.

That’s the operational shift. And early signals suggest that redundancy is giving way to structural rerouting — not as a theory, but as an emergent pattern in port data, platform positioning, and logistics design.

These developments are not, in isolation, proof of full-scale rerouting. But collectively, they describe a logistics environment preparing for prolonged U.S. exposure mitigation:

This is not speculation. This is already being advertised by freight brokers as “compliance strategy” and “tariff-avoidance alignment.” The rerouting logic is operational — even if adoption remains at the early stages.

If U.S. RTR tariffs remain active without a formal exemption process by July 1, 2025, then:

At that point, what has been an adaptive response becomes embedded infrastructure — and rerouting moves from exception to design logic.

On April 3, 2025, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney announced a 25% retaliatory tariff on U.S.-made vehicles that fail to meet the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) content thresholds. The tariff, implemented on April 9, affects approximately C$35.6 billion in U.S. auto exports, targeting vehicles assembled outside North America or using insufficient North American content.

This was not a symbolic response. It was a targeted measure, legally grounded in the retaliatory mechanisms allowed under Canadian law (Customs Tariff Act, s.53(2)), and structured to maintain trade flow with Mexico while directly pressuring U.S. manufacturers. There was no accompanying WTO complaint, nor any bilateral negotiation window offered — only a declarative shift.

Carney’s public statement on April 3 framed the response as proportional, stating:

“The old relationship we had with the United States — as a trusted, rules-based partner — is over. We will build new pathways, and we will protect Canadian workers.”

This marks a break from previous Canadian trade posture. Where prior governments responded to U.S. tariffs with caution and diplomatic restraint, the current Canadian strategy is openly designed to construct alternatives — not in rhetoric, but in logistics.

Canada now occupies a rare role:

This triangulation enables Canada to act as a high-trust staging ground for exporters attempting to maintain access to the U.S. market without entering the U.S. directly.

Observed behaviors:

If RTR remains in place without exception through Q3 2025:

For now, Canada remains aligned with U.S. security structures.

But in logistics? It’s already diverging.

Unlike Canada, Mexico does not signal divergence through rhetoric. Its approach to the Reciprocal Tariff Regime (RTR) has been quiet, transactional, and infrastructural. That silence is not passivity — it’s functionality. Mexico’s value in the emerging North American rerouting landscape is not built on trust or alignment. It is built on elasticity.

The maquiladora system, established in the 1960s and expanded under NAFTA and USMCA, already provides a pre-authorized mechanism for transforming foreign-origin components into tariff-compliant finished goods. Under USMCA, goods that meet regional value content (RVC) thresholds are eligible for duty-free export to the United States. For many firms, especially in electronics, automotive, and apparel, this means that minor final assembly in Mexico qualifies the product as North American.

This system is already functioning at high capacity. As of Q1 2025:

These are not signs of abuse. They are signals of the system performing exactly as designed.

Mexico offers three advantages that make it central to U.S. rerouting behavior:

Large manufacturers are already positioned to exploit these advantages. But now, mid-tier firms and contract manufacturers — particularly those sourcing from Southeast Asia — are moving to evaluate Mexican partnerships not as redundancy, but as first-line routing.

Mexico’s flexibility comes with vulnerabilities:

If RTR remains in place through Q3 2025, and Canada’s tariff shield begins drawing U.S. scrutiny, firms with low-margin, high-volume goods (apparel, home goods, electronics) will likely:

In this context, Mexico is not a bridge between systems.

It is the system that allows the bypass to function.

As of Q2 2025, no country has formally announced supply chain realignment away from the United States. There have been no high-profile rerouting declarations, no multilateral blocs calling for decoupling, and no coordinated trade bypass efforts. But this lack of official messaging is not a sign of stasis — it’s a feature of how logistical restructuring occurs.

Supply chains don’t realign through political statements. They shift through:

The following indicators are operationally active and serve as baselines for monitoring the hardening of bypass architecture in Canada and Mexico.

These are non-confirmed but trackable conditions that would indicate structural realignment is occurring:

If these thresholds are reached or exceeded, the system will have crossed into logistics irreversibility — where bypassed routing logic becomes not just available, but default.

The United States has not lost market dominance. It remains the world’s largest importer of goods and services, the anchor of the dollar system, and the primary destination for North American freight. But as of Q2 2025, it is beginning to lose operational visibility — and with it, enforcement leverage.

The shift is not geopolitical. It is infrastructural. And it is already underway.

When a good enters the U.S. directly:

When the same good is imported into Canada or Mexico, modified, and re-exported:

This creates a blind spot — not in scale, but in fidelity. The U.S. retains macro visibility, but loses granularity on supply origin, corporate routing logic, and tariff evasion strategy.

Prior to 2025, U.S. market access was enforced by three primary mechanisms:

RTR functionally disables two of these. There is no WTO process underway. Exclusion waivers no longer exist. U.S. Customs is now operating under a regime that leaves no incentive to comply and no procedural appeal.

This removes the predictability of compliance — the very feature that made the U.S. system globally sticky. Without it, trade partners do not resist. They reroute.

If reassembly and rerouting become normalized:

In that context, the U.S. does not appear protectionist.

It appears unpredictable.

That perception — not the tariff levels — is what drives systemic avoidance.

As of April 2025, global trade rerouting remains informal, partial, and plausibly deniable. But several identifiable flashpoints could accelerate or harden this shift into permanent infrastructure.

If the U.S. deems Canadian routing strategies a form of circumvention, it could:

This would fracture the current buffer architecture — and may force Canada to choose between regulatory independence and U.S. alignment.

Trigger condition: Public accusation from USTR or CBP regarding systemic Canadian facilitation of RTR bypass

Trigger condition: Shift in customs policy language, rollback of Carney-era tariff retaliation, cancellation of bonded zone permits or FDI incentives

As of Q2, neither the EU nor Japan has issued formal trade retaliation. If either escalates:

Trigger condition: EU or Japan announces retaliatory tariffs or joint G7 trade position opposing RTR

These flashpoints are not speculative.

They are active variables in the system now.

Each one tightens or unravels the viability of the detour.

That change is not ideological — it’s mechanical.

And it’s irreversible if current patterns hold.

RTR didn’t break the system. It just clarified its fault lines.

It proved what many logistics planners, customs brokers, and regional partners had already begun to assume: that the U.S. is now a risk factor, not a neutral trade platform.

What follows isn’t decoupling. It’s circumvention — by design.

Canada and Mexico are not replacements for the United States.

They are pressure valves, now being hardened into permanent corridors.

What began as “resilience” has become detachment architecture — slow, boring, logistics-first realignment with no fanfare and no public treaties.

The future of North American trade is still trilateral on paper.

But increasingly, it is bifurcated by enforcement logic:

This brief has not predicted collapse. It has documented divergence.

And that divergence is already being built into how goods move, how certificates are filed, how warehousing is planned, and how risk is priced.

The U.S. is not being left behind.

It’s being routed around.