Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

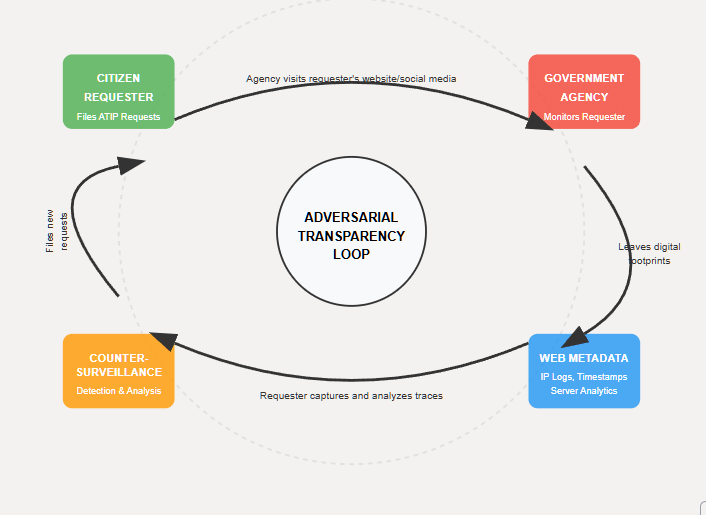

In Canada’s freedom-of-information arena, an unexpected feedback loop has emerged. Citizens file Access to Information (ATIP) requests seeking government records, but evidence shows that federal institutions may respond by quietly monitoring those very requesters through web metadata. Server logs, IP addresses, referrer headers, and session patterns have become a two-way mirror: the government watches who is asking, and in turn, savvy requesters monitor the government’s watching. This dynamic creates an “adversarial OSINT” cycle – an open-source intelligence standoff in which the state and the citizen are each other’s subjects of surveillance. When a FOI requester publishes commentary or runs a website, agencies have been observed visiting, scraping, or even automating queries against the requester’s online content in real time. The requester, in turn, captures those digital footprints as evidence. What begins as a transparency exercise (an ATIP request) mutates into a reflexive spy game, an unseen feedback loop of monitoring and counter-monitoring. This exposé examines that phenomenon in depth – asking what it means for institutional impartiality, legal boundaries, comparative norms, and the future of transparency as an adversarial practice. The goal is to map how metadata itself becomes a battleground in the fight for government accountability.

Canada’s Access to Information Act (and parallel Privacy Act) give citizens a legal right to obtain records from federal institutions. This ATIP regime is often described as quasi-constitutional, meaning it is fundamental to democracy and accountability. By design, the process is meant to be “applicant-blind” – the identity or motive of a requester should not influence how a request is handled. Each institution has a duty to assist requesters impartially, codified in subsection 4(2.1) of the Access to Information Act, which requires making “every reasonable effort” to help the requester and respond completely and without delay. In theory, a request should be processed neutrally, without regard to who asks or why. The Office of the Information Commissioner (OIC) – an independent watchdog – is tasked with investigating complaints when requesters suspect delays, improper denials, or other breaches of the Act. Under section 4(2.1), institutions must not discriminate or retaliate against requesters; they must communicate, clarify, and even accommodate disabilities during the process. This is the legal and ethical baseline.

In practice, however, ATIP gatekeepers (the officials and coordinators processing requests) operate within a stressed system. Backlogs, political sensitivities, and institutional defensiveness often shape how requests are handled. Canada’s system has been criticized as opaque and delay-prone, with gatekeepers sometimes acting as buffers between the public and embarrassing information. The Federal Accountability Act 2007 introduced the duty to assist to curb some of these issues, and recent amendments (Bill C-58) added provisions like section 6.1 allowing agencies to decline vexatious requests with OIC approval. Those measures underscore a tension: the law tries to facilitate access, but also gives agencies tools to push back on requests deemed abusive. This tension can tempt gatekeepers to view certain requesters as adversaries.

Crucially, the identity of the requester is not supposed to matter – yet the incidents below show government actors breaching this principle. ATIP offices and even the OIC itself (which should be scrupulously neutral) have been caught taking an unusual interest in who the requester is, what they publish, or how they might use the information. Instead of the requested records, it is the requester being scrutinized. This marks a troubling departure from the norms of impartial access to information, crossing into surveillance.

Web metadata can speak volumes. Every visit to a website leaves a trace – an IP address (often mapped to an organization), timestamp, user agent, and the resources accessed. To a vigilant site owner, a sudden hit from a government network can signal, “a bureaucrat is reading your post.” Patterns in these logs – such as an unusual burst of activity from a particular department’s IP range – can be pieced together into strategic intelligence about institutional behavior. In this case, a private researcher turned these innocuous data points into a method of adversarial OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence): watching the watchers.

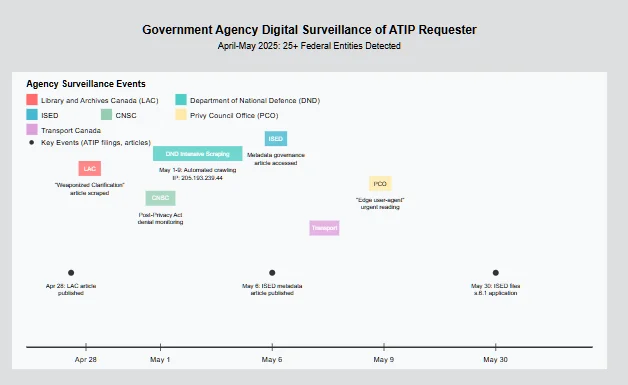

After filing numerous ATIP requests and publishing analyses of agency behavior, the researcher noticed strange visitors in his server logs. For example, the Department of National Defence (DND), via a Shared Services Canada IP, hit his site repeatedly in early May 2025 – not just loading a page or two, but scraping dozens of articles and associated assets in rapid sequence. The automated, “headless” nature of the requests (loading scripts and images at high speed) indicated this was no casual browse by an employee – it appeared to be a deliberate content ingestion script. Similarly, Library and Archives Canada (LAC) was observed performing a structured, millisecond-paced traversal of the site in late April 2025. They even pulled down a specific exposé the researcher had written – titled “Weaponized Clarification,” which criticized LAC’s handling of a Privacy Act request – in its entirety. In essence, the agencies were quietly harvesting intelligence from the requester’s own online publications. The metadata (like which articles they targeted, and when) served as a signal of what the agency was concerned about. For instance, LAC’s scraper zeroed in on an article naming its staff and missteps, suggesting an attempt at damage assessment: the institution was checking what had been exposed about its conduct.

From the requester’s perspective, these server log pings became leads. Each IP address was traced and attributed: Shared Services Canada network blocks revealed the government origin, and in one case the DND-linked IP was cross-identified on a public fantasy hockey site, linking it to specific government employees who unwittingly used the same IP for personal use. This open-source sleuthing confirmed that real DND analysts were likely behind the automated scraping – incredibly, scraping the researcher’s content in between managing their fantasy hockey team, as the timestamps and identities matched. The situation, while almost farcical, revealed a trove of strategic insight. It exposed a counterintelligence weakness in the government: by blending work and personal browsing, and by using official infrastructure for unofficial monitoring, they left an audit trail that a savvy citizen could compile.

The key point is that web metadata turned the tables. What was meant to be a one-way mirror (government observing a citizen) became two-way. The logs and digital crumbs left behind by agencies provided the citizen with a map of institutional reflexes. Each click and crawl said, “We’re worried about this topic” or “We’re checking up on you now.” As one article noted, “Often, the signal isn’t in the primary material. It’s in the metadata… If no triage note exists, why not? If no legal opinion was sought, was the request too routine—or too sensitive?”. In other words, what agencies choose to monitor (or how they respond procedurally) can itself expose their sensitivities and internal state of mind. By treating those server logs as signals, the requester-turned-analyst began assembling a picture of which institutions “flinch” and when.

This approach essentially repurposes OSINT techniques for transparency activism. Rather than using open data to profile a foreign adversary or corporation, here the target is one’s own government agencies, using their inadvertent metadata emissions as a dataset. It’s an inversion of the normal power dynamic: “The federal government monitors its citizens… What it’s not used to is being monitored back. That’s what happened this week.”. The result is that the institutions themselves become the subject of study – their response times, their digital traces, their inconsistencies. This method aligns with what Prime Rogue Inc. (the firm behind this strategy) describes as “forcing decision architecture into the open.” By eliciting and then analyzing metadata, the requester can reveal who within the bureaucracy acts, who delays, who flags an issue to higher-ups, etc., effectively building an “institutional biography” of each agency’s behavior under scrutiny.

Concrete evidence of this phenomenon has surfaced across at least 25 federal entities, painting a consistent reflex pattern. According to the researcher’s audit logs, a wide range of institutions – from central agencies to regulators to departments not typically associated with national security – have been caught in the act of accessing or scraping his online content in the immediate aftermath of ATIP-related triggers. Some did it only once; others dozens of times. Notable examples include:

All these instances form a clear pattern of reflex. The common denominator: whenever the requester pushed the system (by filing many requests, publishing critical analyses, or escalating complaints), the system’s knee-jerk response was to look back at him. It did not do so overtly or through formal channels, but through quiet digital surveillance. One article analogized it to “the same reason an octopus changes color under stress – because something in their environment has shifted.” The institutions perceived a potential threat (to their reputation or operations) and instinctively reached out to gather intel, leaving digital coloration in the form of log entries. Crucially, this wasn’t a coordinated strategy – “It’s not CSIS or the RCMP kicking in the door… It’s dumber than that. It’s a thousand bureaucrats, analysts, comms officers, and bored policy interns tapping through my pages in a desperate act of… what, exactly?”. In short, it’s a bureaucratic reflex: uncoordinated, often clumsy, but pervasive. One could call it a form of “bureaucratic self-defense mechanism” – the state’s immune system responding to an irritant. But as we’ll see, this reflex has significant implications because it undermines the neutrality of the access regime and blurs the line between legitimate administration and illegitimate surveillance.

That blur – between normal procedure and surveillance – raises questions about statutory, ethical, and constitutional lines. When federal actors covertly monitor a requester’s online activity during an open ATIP matter, they jeopardize their duty of impartiality and fairness. Under the Access to Information Act, section 4(2.1) embodies a duty to assist “without regard to the requester’s identity” (in spirit, if not in exact wording). If an institution is checking who the requester is, what he says on his blog, or whether he’s criticizing them on social media, that suggests they are considering his identity and motives – consciously or subconsciously. This contravenes the applicant-blind principle. The U.K.’s Information Tribunal put it succinctly: “in dealing with a Freedom of Information request there is no provision for the public authority to look at from whom the application has come… FOIA is applicant and motive blind.” By “licking the glass” of the requester’s server window, Canadian officials violated that principle of blindness, introducing bias into what should be an impartial administrative process.

Moreover, for the Office of the Information Commissioner, impartiality is paramount. The OIC acts almost like an ombudsperson or tribunal for disputes. If OIC staff engaged in metadata surveillance of a complainant (even if just out of curiosity), they risk creating a perception of bias. For example, in the ISED case, the OIC had to decide whether ISED’s mass “vexatious requester” claim was valid. If OIC personnel were reading the requester’s personal blog – where he (understandably) lambasted ISED’s behavior – one fears they might form judgments about him that could influence their decision. Impartiality under the Access to Information Act s.4(2.1) isn’t just for institutions processing requests; arguably it extends to the Commissioner’s handling of complaints: the focus must be on the facts of delay or disclosure, not on whether the complainant is a squeaky wheel or a gadfly. The OIC’s eventual silence and reluctance to quickly rule on ISED’s application (discussed in the next section) suggest a possible conflict: they may have been cowed or influenced by the extraordinary nature of the situation. If so, that undermines the very purpose of having an independent arbiter.

From an ethical standpoint, this kind of surveillance flirts with retaliation. Government officials accessing a private citizen’s publishing infrastructure (website, LinkedIn, etc.) in direct response to that citizen exercising a legal right could be seen as intimidation or harassment, even if subtle. The Savory Tort blog on FOIA retaliation in the U.S. notes that using public-records requests is protected activity, and that retaliation against requesters, while often hard to prove, is a real risk. In one egregious U.S. case, a town official literally sent a burdensome demand to a requester as payback for his FOIA request. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals recognized that as a potential First Amendment violation (retaliation for petitioning the government). In Canada, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms does not explicitly guarantee the right to information, but section 2(b) (freedom of expression) and section 2(d) (freedom of association) could be argued to cover the act of requesting information and sharing it. Certainly, if the government’s actions – e.g. covertly compiling intelligence on a requester – had a chilling effect on his willingness to continue making requests or speaking out, one might see an infringement on expressive freedom or the right to seek accountability.

Section 7 of the Charter (life, liberty, security of the person) is traditionally about deprivations by state that violate fundamental justice. It might come into play if, say, the government’s surveillance of a requester (especially one who exposed military or security issues) put him at risk or caused serious psychological harm (e.g. intimidation causing fear for safety). While that’s a stretch, one could argue that the principles of fundamental justice include not abusing legal processes (like ATIP) to harm someone. A retaliatory surveillance campaign by officials might be characterized as an abuse that offends those principles.

More concretely, Section 15 of the Charter (equality rights) is relevant given the role of disability and personal characteristics in this saga. The requester, Kevin J.S. Duska Jr., has a visual impairment and documented anxiety disorders. He explicitly informed agencies of his disability and need for accommodation in ATIP communications. Yet ISED, rather than accommodating, seemed to weaponize this information – sending him inaccessible files and then citing his struggles as evidence of vexatious behavior. For instance, ISED provided clarification requests in the form of Excel spreadsheets, despite knowing he had amblyopia (a condition making it hard to read dense spreadsheets). This not only violates the duty to assist (which includes assisting disabled requesters in an accessible way), but also edges into disability discrimination. Section 15 guarantees equal benefit of the law without discrimination, and the Access to Information Act is a law conferring a benefit (the right to obtain government information). If a disabled person is effectively denied that benefit or faces extra burdens because of disability (or if they are targeted for who they are), it raises a Section 15 concern. As Duska put it, “They didn’t treat me as a human being with access needs. They treated me as a problem to be neutralized.” The digital trail of surveillance exacerbates this, because it shows the institution reacting to the person (and his perceived “troublemaking”) rather than neutrally fulfilling his requests. In a Charter lens, that looks like a distinction drawn on improper grounds – be it disability, or simply the fact that he’s an outspoken critic (which might be seen as discrimination based on political opinion, an analogous ground).

Furthermore, privacy rights are in play. Ironically, many of these events occurred in the context of Privacy Act requests (where he was requesting his personal information from agencies). The Privacy Act is meant to protect individuals’ data and give them access to it. If an agency, during a Privacy Act request, turns around and collects more personal information about the requester (like scouring his LinkedIn or website for intel), it contravenes the spirit of privacy protection. Government institutions are limited in how they can collect and use personal information; typically, they can only collect what relates directly to an operating program or activity (Privacy Act section 4). Monitoring a requester’s blog or CV likely falls outside any legitimate program activity – it’s purely for the institution’s self-interest. Thus, it arguably violates federal privacy principles and perhaps the Privacy Act itself. Certainly, it would offend the Office of the Privacy Commissioner if an institution were found to be compiling dossiers on requesters.

In sum, the digital trail left by these agencies suggests multiple lines crossed: breach of the duty to act impartially and assist, possible intimidation violating constitutional values, and discriminatory or privacy-invasive conduct. These aren’t just theoretical concerns. They manifest in how the requester’s access rights were handled – or mishandled. We see it clearly in the case study that follows, where ISED’s attempt to shut down the requester and the OIC’s handling of that attempt come under the spotlight.

But in a savvy countermove, within hours of ISED’s application hitting the OIC, the requester withdrew or significantly narrowed over 70% of those requests. By May 31, he had sent a detailed email to ISED and the OIC, documenting the withdrawal of 67 requests, conditional withdrawal of 7, and major revision of 30 others. This was explicitly framed as a gesture of good faith – he showed that if volume was the issue, he was willing to reduce it dramatically to address their concerns. Notably, he emphasized that he did this “without prejudice” (not conceding that the requests were improper) and reminded them of his disability and the need for accommodation which had not been met. In other words, he called ISED’s bluff: “You say you’re overwhelmed – fine, I’ll drop most of it immediately, now what’s your excuse?”

The immediate result was silence from ISED. The department did not update its 6.1(1) application to acknowledge that most requests were gone. It left the OIC with an application that was largely moot on its face (complaining about dozens of requests that no longer existed). This “silence as strategy” was interpreted by the requester as evidence that ISED’s goal was never really about workload relief, but about removing a troublesome requester at all costs. As he put it, “If they’re not correcting the record, what are they really protecting?” The answer: control. They wanted to establish a precedent (or at least send a message) that they could swat down someone filing inconvenient ATIPs. By not withdrawing or amending their accusations even after the issues were addressed, ISED essentially left a cloud of insinuation over the requester’s reputation (painting him as an “abuser” in official filings) with no regard for the truth. This stands in stark contrast to the law’s intent – 6.1(1) is meant as a last resort for true abuse, not a quick first strike to avoid answering uncomfortable questions.

Critically, during this period, the surveillance reflex was in full swing. While ISED’s ATIP office and lawyers were busy drafting the 6.1(1) application, someone at ISED was also monitoring the requester online. Recall, on May 6, an ISED IP scraped his blog after he published an article on ATIP metadata failures. And in early April, internal ISED chat logs (later obtained by the requester) show staff explicitly discussing who he might be: “Where is this coming from? I just creeped a guy on LinkedIn with the same name and he’s ATIPing everyone.” This snippet (from an ISED employee, Nidal Islam, as shown in the chat screenshot) reveals that ISED personnel, upon seeing an influx of requests, immediately resorted to “creeping” the requester on LinkedIn to gather intel. The same staff member repeated “Looks like he has a company that just does ATIPs” (paraphrasing the chat at 9:05 a.m.) – referencing Prime Rogue Inc., the firm, and implying they viewed him as someone making a profession or crusade of FOI. This is blatant proof that ISED’s reaction to an active ATIP requester was to research the person behind it, rather than treat the requests at face value. It underscores the retaliatory reflex: instead of focusing on the content of the requests, they focused on the character of the requester.

When ISED filed its application to OIC, it even accused the requester of “weaponizing transparency” – claiming he was using the ATIP system to harass or harm the department’s staff (for example, by asking for records about ATIP staff mental health, which ISED itself had brought up in correspondence). This terminology—weaponized transparency—frankly flips the script: the requester was seeking transparency to expose problems, but the institution framed that very act as a weapon. Meanwhile, the truly weaponized behavior apparent is ISED’s surveillance and stonewalling.

Now consider the Office of the Information Commissioner (OIC) role here. ISED’s section 6.1(1) application put the OIC in a position to judge the situation. As of the latest updates, the OIC had not issued any decision or even an acknowledgment of the application for weeks. This silence is unusual given the urgency (a requester’s entire portfolio of requests was frozen pending OIC’s leave). The requester and observers speculated that OIC might be hoping the issue would quietly go away – e.g., that ISED would withdraw the application now that requests were withdrawn, sparing OIC from a thorny ruling. There’s a risk that “the OIC, overwhelmed and under-resourced, might try to quietly shelve the case… allow ISED to withdraw without penalty… fail to recognize the fundamental legal questions on the table.” Those fundamental questions include the allegations of disability-based non-assistance and the propriety of ISED’s tactics. If OIC avoids ruling, it effectively sidesteps accountability for ISED’s behavior, possibly emboldening similar moves by other agencies.

Why would the OIC be so timid? The context suggests they were confronted with a scenario with no precedent: a department launching a massive pre-emptive strike on a prolific requester who is simultaneously auditing the system and catching agencies in the act of surveillance. The OIC itself may have become part of that “loop” – aware that the requester was documenting everything (indeed, OIC’s own website hits might be monitored). We saw that in one of his articles, he pointed out that every time they visit, it becomes a new record, a new Privacy Act request. The OIC could fear that any misstep on their part will also become public fodder. In short, the overseer is not used to being overseen in this manner. This may induce a kind of institutional paralysis – a “reflexive quiet.”

The retaliatory reflex thus has two facets here: ISED’s aggressive retaliation (application and surveillance) and OIC’s quiet recoil (potentially shrinking from a decisive confrontation). As the Prime Rogue analysis bluntly stated, “The risk is that the OIC… might let the matter vanish into the administrative ether… To do so would be to endorse the weaponization of the system against those who use it most carefully.”. In other words, if the regulator doesn’t step up, it sends a message that agencies can get away with these tactics. It would confirm requesters’ worst fears that the transparency regime is stacked against them when it really counts.

The case study highlights the human toll and irony too. Duska, believing in good faith engagement, worked overnight to narrow his requests – a Herculean effort given his disability (he manually processed and refiled dozens of requests in accessible ways). Yet ISED gave no acknowledgment, essentially punishing him for trying to cooperate. He noted bitterly that “I drained the flood… and they still tried to build an ark”, meaning even after he removed the burden, they continued with the narrative of being burdened. This one-liner encapsulates the retaliatory mindset: the agency was determined to cast him as the problem, regardless of facts.

In sum, the ISED-OIC episode illustrates a full-spectrum adversarial clash: mass requester vs. embattled agency vs. cautious watchdog. It shows how metadata evidence (like internal emails about “creeping on LinkedIn” and log trails of website hits) becomes crucial in exposing what’s really happening behind the formal letters and legal submissions. Absent those meta-level insights, it would simply be ISED’s word against the requester’s. But the metadata provided an objective chronology of behavior that strongly supports the requester’s claims of bad faith and retaliation.

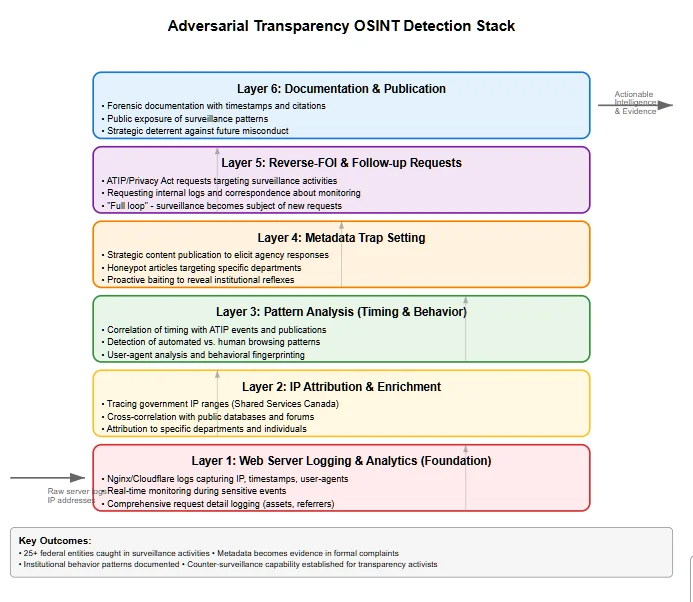

Faced with this covert monitoring, the researcher developed a methodology – essentially a surveillance detection stack – to systematically capture and leverage metadata for accountability. This approach can serve as a model for other transparency watchdogs or tech-savvy requesters concerned about government retaliation. Key components of the methodology include:

Methodology for Detecting Government Monitoring via Web Analytics

Foundation: Robust logging infrastructure to capture all visitor metadata

Technical Implementation: Setting up comprehensive server logging is the cornerstone of any surveillance detection system. Modern web servers like Nginx provide extensive logging capabilities that can capture granular details about every visitor interaction.

Intelligence: Tracing suspicious IPs to their government sources

OSINT Techniques: Open Source Intelligence gathering is crucial for identifying government network blocks and attributing suspicious traffic to specific agencies.

Detection: Distinguishing surveillance from legitimate visits

Behavioral Analytics: Understanding the difference between human browsing patterns and automated surveillance tools is essential for accurate detection.

Proactive: Strategic content deployment to trigger monitoring

Honeypot Strategy: Creating compelling content that specifically targets government monitors allows for controlled surveillance detection experiments.

Accountability: Using transparency laws against surveillance

Legal Framework: Freedom of Information and Privacy Act requests become powerful tools for creating accountability around surveillance activities.

Transparency: Public accountability through detailed documentation

Public Accountability: Documentation and publication create permanent records and public pressure that can deter future surveillance activities.

Click on IP addresses to see attribution – Learn how to identify government network blocks

Server logs, IP addresses, timestamps, user agents

Pattern recognition, timing correlation, behavior analysis

IP lookup, agency identification, cross-referencing

Evidence compilation, timeline creation, proof gathering

FOI requests, official inquiries, transparency actions

Public disclosure, accountability pressure, deterrence

In building this surveillance detection stack, the researcher demonstrated that even a lone individual (with some tech skills) can effectively audit multiple government bodies at once. It’s an asymmetric strategy: one person’s server logs versus an entire federal apparatus. Yet, as shown, it yielded results. The stack approach could be replicated: journalists, activists, or any frequent FOI requester could set up their own website or tracking system and watch for government domains hitting their content. Over time, patterns might emerge to indicate if certain agencies habitually background-check requesters. It’s akin to installing a CCTV to catch the guard peeking in your window.

One risk of this methodology is that it might drive the surveillance deeper underground. Agencies could start using VPNs or non-attributable networks to read targets’ content (e.g. using personal phones on 4G network or anonymizing tools), thus avoiding leaving a government IP trail. Indeed, after embarrassment, one might expect staff to be warned “don’t read that site from work!”. However, doing so itself is telling – if agencies feel the need to hide their monitoring, it tacitly admits it was wrong in the first place. Also, technical users can sometimes still detect patterns (for example, sudden hits from a major ISP at 9am that correlate to office hours might arouse suspicion too). The cat-and-mouse could continue, but the methodology can adapt.

In summary, the surveillance detection stack comprises logging, attribution, pattern analysis, baiting, reverse-requests, and public exposure. It transforms raw metadata into a potent form of accountability leverage. As the researcher quipped, “they are triggering the very surveillance they think they’re managing” – every time the agencies tried to stealthily check on him, they created new data that he then used to check on the. The hunter became the hunted in the data realm.

A New Doctrine for Civic Activism & Government Accountability Through FOI Intelligence

Formalizes FOI metadata analysis as intelligence gathering. Every request becomes a probe for both information and institutional behavior patterns.

Challenges power asymmetry through legal transparency tools. Transforms passive requesters into active investigators of government conduct.

Submit information request while simultaneously monitoring all process metadata

Gather response times, email headers, web logs, communication tone patterns

Analyze institutional responses to identify failures, conflicts, and systematic issues

Use evidence to hold institutions accountable and expose patterns of misconduct

“Once the institutions realize they’re being watched, they start to act like it.” This doctrine aims to restore public trust by exposing misconduct and forcing democratic institutions to withstand the scrutiny they should naturally expect in a transparent society.

To codify and defend this doctrine, one can point to its dual nature: it is both a research method and a civil resistance strategy. As a research method, it formalizes what this case has demonstrated. It says: when you engage in FOI, concurrently gather and analyze process metadata – response times, email headers, web logs, tone of communications, etc. – because those reveal as much about government accountability as the content of the released documents might. The doctrine could be documented in guidelines or academic papers as a methodology: “Metadata as Method,” where each FOI request is a probe not only for information but also for eliciting behavior. Indeed, Prime Rogue Inc. introduced “Echo (12b)” in the Privacy Act context as a doctrine to classify when an institutional failure has occurred (e.g., when a conflicted official denies a request without proper grounds). They outlined conditions like the duty to assist being breached and conflicts of interest, labeling such events as Echo(12b) escalations. This is part of adversarial transparency OSINT: naming and standardizing the failure modes so they can be recognized and addressed. Similarly, Operation Recursive Enema (humorously named) is an ongoing project making a doctrine out of monitoring metadata reflexes.

As a civil resistance strategy, Adversarial Transparency OSINT is fundamentally about challenging power asymmetry. In authoritarian or secretive regimes, the state holds all surveillance capability. This doctrine offers a peaceful, legal means for citizens to push back by using transparency laws and public data creatively. It aligns with the philosophy of whistleblowing and watchdog journalism, but extends it to incorporate technical sleuthing. One can defend it on ethical grounds by arguing that democratic governance should withstand scrutiny – if institutions are acting properly, they should not fear their own metadata trail. The doctrine doesn’t involve hacking or anything illicit; it uses open records and the institution’s own disclosures (often compelled by law) to hold a mirror up to them. In Canada, where access to information is part of the law, using that law in an adversarial way is still playing by the rules – just very assertively.

One might attempt to formalize this doctrine through something like a “Transparency Charter” or amendments to the ATIP regime. For instance, FOI laws could explicitly forbid surveillance or retaliation against requesters, giving teeth to the principles. While existing laws imply this (through duty to assist and non-discrimination), making it explicit would validate the doctrine’s concerns. Alternatively, internal policies could be adopted: e.g., the Treasury Board could issue guidance that “monitoring of requester behavior outside the request process is inappropriate.” If agencies know that checking up on requesters could itself be an actionable offense, they might refrain.

The risks of this doctrine include further straining relations between requesters and officials. It can create an atmosphere of distrust – essentially an arms race. The government might react by clamping down in other ways (tightening ATIP regulations, labeling more people vexatious preemptively, or charging higher fees to deter large requests). There’s also a personal risk: an adversarial stance can invite personal attacks or attempts to discredit the requester. Indeed, we see ISED tried to paint Duska as vexatious and even hinted at harassment (despite no evidence). Engaging in this strategy could make one a target of legal action (though unlikely if one stays within law) or simply get blacklisted informally. Another risk is misinterpretation – if a less skilled practitioner tries to mimic this and accuses an agency based on mistaken log data, it could undermine credibility of the movement. For example, not every government IP hit is malicious; jumping to conclusions without thorough analysis could backfire.

Additionally, adversarial FOI tactics might cause collateral damage: agencies might become warier not just of the “troublemaker” but of all requesters, making the climate even less friendly. There’s a possibility of a chilling effect on the agencies’ side: what if staff become so afraid of being profiled that they communicate even less or stop making records (the “oral governance” problem where officials avoid creating any record that could be FOI’ed)? The doctrine must consider that it’s poking at bureaucratic instincts and could have unintended consequences like more secrecy (e.g., officials resorting to phone calls over email to avoid written records that could be tracked).

The rewards of the doctrine, however, are significant. It can lead to systemic change by exposing weaknesses and hypocrisies. For instance, the publicity around these incidents could prompt the Information Commissioner or legislators to update guidelines and strengthen requester protections. It already has proven effective in the short term as a defensive measure – Duska was able to fend off ISED’s broad attack by documenting his good faith and their bad faith, likely saving many of his requests from being thrown out. His meticulous record-keeping means that if this goes to court or a public inquiry, he has a wealth of evidence to make his case, far beyond the he-said-she-said.

Moreover, this approach contributes to the knowledge commons: by publishing the patterns (e.g., which agencies react poorly, which ones respect the rules), other requesters know what to expect. It’s creating an accountability scoreboard. “Once the patterns are exposed—who redacts what, who delays longest, who invokes Cabinet confidence fastest—those patterns don’t go away. They get cited. Reported. Filed as evidence. Weaponized in future complaints. And—eventually—read by new political leadership.” This quote from the analysis underscores the long game: documentation now can influence policy later. Politicians who might not care about one man’s troubles could be swayed when they see that multiple agencies are systematically doing this – it signals a governance problem that requires oversight or legislative fix.

In fact, we see early signs of comparative awareness: other jurisdictions have started to acknowledge similar issues. In the U.S., as noted, lawmakers introduced a Federal Employee Access to Information Act to protect government employees from retaliation when they file FOIA requests as citizens – essentially recognizing that using FOIA should not cost you your job or invite punishment. This implies a principle that could be broadened: no one should face retaliation for using FOI, period. If adversarial transparency OSINT highlights retaliation in Canada, it strengthens the case for such protective measures. The doctrine aligns with evolving norms that treat access to information as an extension of free expression and the right to petition government. Indeed, one U.S. court allowed that a FOIA requester’s retaliation claim could proceed under the First Amendment, treating the FOIA request akin to protected speech in holding officials accountable. That kind of reasoning could migrate into Canadian thought (where Charter section 2(b) might be interpreted to shield the act of requesting information, as part of democratic discourse).

To formally defend the doctrine in jurisprudence, one might invoke the “duty of good faith” in public law. Government exercises of discretion (like using s.6.1 to block requests, or any internal policies of monitoring) must be in good faith and for proper purpose. Adversarial OSINT can gather evidence of bad faith (like ISED’s contradictory behavior) that could be presented in court or to the Commissioner to show an abuse of process. As more cases come to light, this could influence how judges view FOI disputes – they might start asking agencies whether they truly acted impartially. If we had, say, a Federal Court case where an applicant produces logs of an agency spying on him, the court might condemn that and set a precedent that it’s unacceptable.

Finally, public trust is at stake. The doctrine, if successful, actually aims to restore trust by ferreting out misconduct. In the short run, revelations that government departments are effectively spying on requesters might erode trust (citizens might think “the system is rigged”). But shining light on it is the first step to correction. As the adage goes, sunlight is the best disinfectant. The absurdity and “ontological collapse” that the researcher describes – a government caught in a hall of mirrors of its own making – can be the catalyst for reform. It forces a confrontation with the question: Will our institutions adapt and behave better when they know citizens can watch their moves? According to the researcher’s experience, “once the institutions realize they’re being watched, they start to act like it.” In other words, awareness of oversight (even if from an unlikely source) might prompt more self-aware, law-abiding behavior within agencies. That ultimately could improve transparency outcomes for everyone.

The unfolding of this adversarial metadata monitoring has broad implications:

1. Legal Reform of Access Laws: The Access to Information Act may need amendments or at least new regulations to address this gray zone of requester-targeted surveillance. Currently, the law does not explicitly forbid what these agencies did (reading a public website isn’t illegal), but it contravenes the spirit. Legislators could consider adding a provision that no person shall be adversely treated or surveilled by reason of making an access request, creating a cause of action if violated. At minimum, the Information Commissioner could update guidelines to agencies, stating that doing background research on requesters is discouraged except in specific, justified cases (e.g., verifying identity for Privacy Act requests is fine, but trawling LinkedIn is not). The duty to assist could be expanded to a “duty of neutrality” in processing requests. Additionally, the phenomena observed might inform the ongoing discussion of what constitutes a “vexatious” request. If agencies are shown to contribute to the problem (by failing to assist, then complaining of volume), the Commissioner and courts might set a higher bar before granting 6.1 applications – to prevent abuse of that tool.

2. Civil Liberties and Constitutional Interpretation: This case invites a re-examination of how FOI interacts with fundamental rights. Traditionally, Canadian courts said access to information is not a constitutional right per se. But the Charter’s values of democracy and free expression are deeply tied to the ability to seek and receive information. The apparent retaliation and surveillance here bolster arguments that there should be constitutional safeguards around the FOI process. For instance, a Charter argument could be made that Section 2(b) (freedom of expression) protects not just speaking but also the right to receive information and to scrutinize government, implying that punitive actions for doing so violate freedom of expression. There’s also a potential Section 8 issue (unreasonable search and seizure) – typically Section 8 is about privacy expectations, and one might argue that by monitoring someone’s online presence due to an FOI, the state is conducting a search of the person’s private life (although the blog is public, LinkedIn might be semi-public; it’s a murky area). If a court found that kind of surveillance unreasonable or not legally authorized, it could declare it contrary to Section 8. While these are novel arguments, they might gain traction as awareness grows. At the very least, civil liberties advocates (like the Canadian Civil Liberties Association) may take interest and issue statements or intervene in cases to assert that FOI requesters must be free from intimidation, tying it to Charter principles.

3. Oversight and Watchdog Institutions: The OIC itself may be forced to evolve. If the watchdog is caught in a conflict of interest (being both a subject of metadata tracking and an arbiter), perhaps a more robust oversight is needed. For example, a parliamentary committee could review these incidents, calling in officials from ISED, LAC, etc., to answer why they engaged in such monitoring. This has happened in other contexts (e.g., committees have investigated government surveillance programs). Public exposure might prod the OIC to make a firm pronouncement that it considers such behavior unacceptable and will treat it as evidence of bad faith in any complaints. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) might also get involved, since some of the behavior touches personal information. OPC could assess whether monitoring a requester’s social media or site is a violation of Privacy Act provisions by the institutions involved.

4. International Norms and Parallels: Globally, if Canada addresses this, it could set a precedent. Other democracies might follow with their own rules. The U.K., for instance, already had an incident some years ago where a council was caught spying on a journalist who made FOI requests (using covert surveillance under RIPA, a UK law). The uproar led to guidance that such surveillance should not target FOI users. The adversarial OSINT doctrine could export; one can imagine FOI activists in other countries adopting similar tactics. Conversely, less democratic regimes might use Canada’s example to justify their surveillance of dissidents (“even Canada does it”). So Canada has a chance to be a leader by openly condemning it. It’s noteworthy that FOI is often used by journalists and activists who are also likely under state surveillance by security services in some countries. The difference here is the surveillance is by the very offices that are supposed to handle the requests. It blurs into a kind of soft political policing. If left unchecked, it could discourage people from using FOI – harming transparency in the long run.

5. Ethical Training for Bureaucrats: There is an ethical lapse evident among the civil servants in these stories. They likely didn’t see “peeking at the requester’s website” as wrong – perhaps even saw it as due diligence (“who is inundating us with requests?”). This suggests a need for better training and a cultural shift. Public servants should be educated that FOI requesters are exercising a right, and treating them as suspects or enemies is unethical. Instead of asking “how do we deal with this person?”, they should ask “how do we fulfill our duty under the law?”. The presence of mocking (the LinkedIn “creeping” comment) and dismissive attitudes in internal chats shows a culture problem. Ethics codes for the public service do emphasize values like respect, integrity, and the rule of law. Arguably, snooping on a requester violates those values. Perhaps this needs to be made explicit in ATIP officer training.

6. Surveillance Ethics and Openness: On a philosophical level, this scenario flips the usual surveillance debate on its head. Typically, state surveillance is justified by security or enforcement needs. Here, it was driven by institutional self-interest and fear of accountability – a clearly unethical basis. It raises the question: should government monitoring of public discourse be logged and disclosed? Perhaps every time a government system accesses a citizen’s website or social media (for non-law-enforcement reasons), that itself should be recorded and be ATIP-able. Right now, a lot of this monitoring is informal and not logged as an “official act”. For instance, if an analyst just opens a browser, there’s likely no permanent record internally that “IP X visited site Y at time Z” (unless caught by external logs). The researcher cleverly made it an official record by catching and then asking for it. This could lead to a push for formalizing any such monitoring – e.g., requiring a reason and approval if an employee wants to surveil a requester. Such measures, however, might be hard to implement without huge bureaucracy, but the ethical line is that monitoring should only be for legitimate purposes, never to gain unfair advantage in an FOI process.

7. Trust and Public Perception: If this story gains wider attention, the average citizen might lose trust in the access regime – thinking “if I make a request, will the government start spying on me too?” This is especially concerning for vulnerable groups or whistleblowers who might use FOI. The chilling effect is real: one might self-censor requests or not ask uncomfortable questions, to avoid being flagged. This undermines the whole point of FOI, which is to enable anyone to seek information without reprisal. Therefore, the institutions involved have an interest (if they think long-term) in restoring trust. They could publicly apologize or commit to refrain from such practices. Doing so would be an admission of guilt, which they might avoid, but it could salvage some trust. Conversely, doubling down or staying silent could lead to public calls for stronger action (even legal action against the agencies for misconduct).

In sum, the implications radiate outward from a niche issue (web logs after FOI requests) to fundamental questions of governance. It tests whether the transparency system can itself be transparent. The ethical maxim “Who watches the watchers?” is answered here by: the citizens can, if they are clever enough. But citizens shouldn’t have to resort to that; the system should police itself. Right now, it isn’t – so external adversarial oversight has stepped in. This may signal that formal oversight (like the OIC) needs more powers or that new independent bodies are needed to audit how requests are handled behind the scenes.

The Canadian transparency regime is facing a stress test – one it never anticipated. What began as a frustrated citizen’s deep dive into ATIP delays has morphed into a mirror held up to government’s reflexes and vulnerabilities. The metadata – those innocuous logs and timestamps – have become a litmus test for the integrity of the access process. They reveal an uncomfortable truth: when pushed for transparency, parts of the state recoiled into opacity, even surveillance.

This saga affirms that “this was never just about IP logs… it was about what those logs revealed – not about me, but about them.” They revealed that institutions are watching, but more importantly, “they don’t know how to stop.” In a modern digital democracy, this is a pivotal challenge: can our government agencies adapt to an era where citizens have new tools to hold them accountable in real time? Or will they double down on defensive secrecy?

Optimistically, the exposure of this adversarial loop could prompt positive change. It’s an opportunity to reinforce the norms that FOI was built on: impartiality, anonymity of requesters, and no retaliation. If those norms are codified and respected, metadata monitoring by agencies would cease because it’d be clearly out of bounds. Requesters wouldn’t need to run metadata counter-operations to ensure fairness.

However, if the system fails to respond – if the OIC remains silent, if no one reins in the rogue reflex – then metadata will continue to test the regime. Each new ATIP activist may take a page from this playbook, turning the government’s digital footprint into evidence of institutional character. We might see a future where watchdog groups routinely publish “access metadata reports,” rating agencies on whether they peep at requesters or play fair. This transparency of the transparency-process itself would be an ironic but necessary layer of oversight.

Ultimately, the conceptual loop has philosophical implications. It forces us to ask: What is the purpose of transparency laws? If it’s to empower citizens and improve governance, then the law cannot be used as a pretext to target those who use it effectively. The moment that happens, the moral foundation of the law erodes. In this Canadian case, one citizen’s relentless pursuit has momentarily turned the bureaucracy inside-out: “the institutions themselves become the dataset… a government caught between knowing it is visible and not knowing how to process being watched.” The hope is that this discomfort will drive a cultural shift – that government will become more self-aware and self-correcting.

In closing, metadata – these digital echoes of interactions – has proven to be a powerful tool of truth. It has shown patterns of behavior that no access request could directly ask for. It has also shown that citizens can wield information-age tools creatively to defend their rights. The question for Canada’s transparency regime is whether it will evolve to meet this challenge or resist until it breaks. As one analysis framed it, “This isn’t national security. It’s Operation Recursive Enema. And we’re just getting started.” In less cheeky terms: the scrutiny of the scrutineers will likely continue until accountability is achieved. Metadata, in the end, may very well be the unlocking force that tests and ultimately strengthens the access regime, ensuring that openness is not just a promise on paper, but a practice – one that even the gatekeepers must honor under watchful eyes of the public.

[…] Overuse or Potential Abuse – Shielding Metadata Surveillance and Profiling? […]

[…] The question becomes: what happens when the transparency regime itself becomes the threat to transparency? […]