Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Key Finding:

Key Developments:

Geopolitical and Strategic Implications:

Conclusion & Outlook:

✔ Will Canada fully withdraw from the F-35 program?

✔ How will the U.S. respond to Canada’s OTHR deployment?

✔ Could NATO adjust its interoperability requirements to accommodate Canada’s shifting procurement strategy?

✔ Will further non-American defense deals emerge in the coming months?

Canada’s defense autonomy trajectory is not yet irreversible, but these decisions signal a fundamental recalibration of its strategic posture in response to emerging geopolitical threats and shifting alliances.

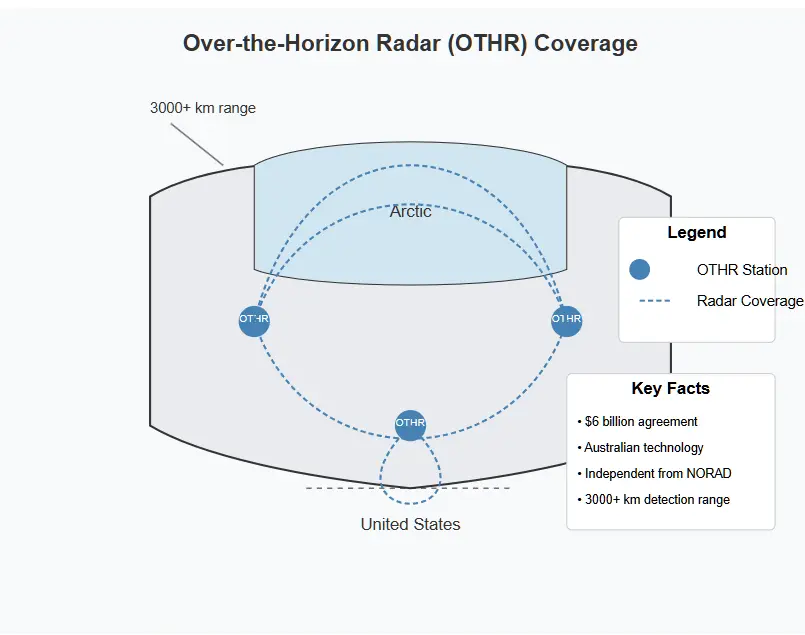

In March 2025, Canada secured a $6 billion agreement with Australia for the procurement of an Over-the-Horizon Radar (OTHR) system. This acquisition represents a fundamental shift in Canada’s defense posture, as it removes U.S. oversight from Arctic surveillance and grants Canada a fully autonomous early warning capability. The technology, adapted from Australia’s Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN), allows for long-range detection of aircraft, missiles, and naval vessels, significantly enhancing Canada’s ability to monitor both Arctic and Southern airspace.

This decision aligns with Canada’s broader strategy to reduce dependency on U.S. military systems while reinforcing its sovereignty over Arctic defense operations. Unlike traditional radar systems, which are constrained by the Earth’s curvature, OTHR extends detection ranges beyond 3,000 kilometers, covering both Arctic waters and southern airspace, including potential U.S. military movements near the Canadian border.

The primary objective of this system is to secure Canadian Arctic sovereignty and establish a defense buffer against potential threats, but its implications extend beyond northern surveillance. By excluding the U.S. from its operational control, Canada has broken its historical reliance on NORAD-managed radar networks, a move that could have long-term consequences for North American defense relations.

The system’s ability to provide continuous surveillance across both the Arctic and Canada’s southern approaches is particularly significant. While officially positioned as a northern security measure, the radar’s coverage also enables tracking of aircraft and military activity near the U.S.-Canada border. This creates a new dynamic in bilateral defense relations, as Canada will now possess an independent monitoring capability that does not require U.S. intelligence sharing or approval.

Operationally, the OTHR system also strengthens Canada’s early-warning capabilities against potential incursions from Russian and Chinese forces in the Arctic, ensuring that Canadian forces receive direct, real-time threat assessments rather than relying on U.S. military priorities within NORAD.

Canada’s historic reliance on U.S.-controlled surveillance has placed significant constraints on its ability to conduct autonomous military operations in the Arctic. By implementing its own OTHR network, Canada removes a key U.S. intelligence gatekeeping mechanism, effectively ensuring that the Canadian government—not Washington—dictates how and when threat information is shared with allies.

This move follows a broader trend in Canadian defense procurement, where Ottawa is actively seeking to diversify military partnerships away from sole reliance on American defense contractors. The decision to purchase radar technology from Australia rather than relying on Raytheon or Lockheed Martin indicates a deliberate shift in military strategy, reinforcing alliances with Five Eyes partners outside of direct U.S. influence.

Beyond sovereignty concerns, Canada’s OTHR also has implications for NATO coordination. While the system allows for greater cooperation with European allies, its exclusion of the U.S. raises questions about how Canada will integrate its new surveillance capabilities into NATO defense frameworks without direct American oversight.

Australia’s JORN system, which serves as the foundation for Canada’s OTHR, was developed to monitor air and naval activity in the Indo-Pacific region, specifically targeting threats from China, Indonesia, and other regional actors. While Canada’s system will operate under very different climatic conditions, the core principles remain the same. OTHR’s ability to detect aircraft, submarines, and missile launches from thousands of kilometers away provides an early-warning advantage previously unavailable without U.S. military support.

The Canadian system, however, will require significant cold-weather adaptations. Unlike Australia’s JORN, which functions in desert conditions, the Canadian OTHR must withstand Arctic ice buildup, extreme low temperatures, and seasonal ionospheric disruptions. These factors introduce new technical challenges that will need to be addressed before the radar network becomes fully operational.

Despite the significant defensive and sovereignty benefits of OTHR, this acquisition is not without risks.

Political Risks

The most immediate concern is the U.S. reaction to Canada establishing an independent surveillance network that effectively replaces NORAD’s Arctic monitoring capabilities. While Washington has not yet publicly opposed the decision, there is a high probability of diplomatic pressure to either integrate the system into U.S.-led networks or limit its operational independence.

Additionally, Canada’s decision to exclude American defense firms from this procurement could exacerbate existing tensions between Ottawa and Washington, particularly given Trump’s increasingly aggressive stance toward Canadian sovereignty. The fact that OTHR can also monitor southern airspace introduces new intelligence asymmetries, as Canada will now have access to early-warning data without sharing it through U.S. intelligence channels.

Technical and Logistical Risks

Cold-weather adaptation remains a significant challenge for Canada’s version of the OTHR system. Unlike previous radar installations in the Canadian Arctic, which relied on NORAD’s short-range detection systems, the new radar network will require customized engineering solutions to ensure uninterrupted long-range performance in extreme conditions.

Another potential issue is interoperability with NATO and allied intelligence-sharing frameworks. While Canada is deepening military partnerships with Australia and European defense firms, integrating OTHR into a multi-national surveillance network could prove complex. If Ottawa intends to restrict U.S. access to OTHR intelligence, it may face additional pressure from NATO partners who rely on U.S.-led intelligence-sharing agreements.

Despite these risks, the acquisition of OTHR represents the most significant step Canada has taken toward strategic defense independence in decades. For the first time, Canada will possess a long-range, fully autonomous surveillance capability, reducing its dependence on U.S. military infrastructure and enhancing its ability to control Arctic defense operations without foreign oversight.

The broader implications extend beyond Canada’s military posture. With Trump openly discussing annexation rhetoric and escalating tensions over U.S.-Canada security policy, Ottawa’s decision to invest in independent military technology signals a clear intent to reinforce national sovereignty against both external and allied pressures.

From a defense policy perspective, this acquisition sets a precedent for future procurement decisions, reinforcing the trend toward military diversification and European-Australian defense cooperation. While it remains to be seen whether the OTHR system will lead to further reductions in U.S. defense involvement, it is clear that Canada is actively restructuring its national security framework to operate with greater autonomy.

The OTHR acquisition marks a turning point in Canada’s strategic defense posture, providing an autonomous Arctic surveillance capability while simultaneously reducing dependence on NORAD and U.S. intelligence networks. By excluding American firms from this procurement, Canada has asserted greater control over its military operations, signaling a wider realignment in its defense procurement strategy.

The implications of this move are far-reaching, particularly in the context of U.S.-Canada tensions, NATO interoperability, and Arctic sovereignty disputes. While the technical challenges of implementing cold-weather radar operations remain, the long-term strategic benefits outweigh the risks.

As Canada moves forward with this system, key questions remain. How will the U.S. respond to Canada’s exclusion of NORAD from Arctic surveillance? Will NATO adapt to a Canadian-led intelligence-sharing framework, or will pressure mount to reintegrate with U.S.-led systems? More critically, will this acquisition set the stage for further defense procurement shifts, accelerating Canada’s decoupling from U.S. military suppliers?

One thing is certain: Canada has just crossed a critical threshold in military independence, and the OTHR acquisition is only the beginning.

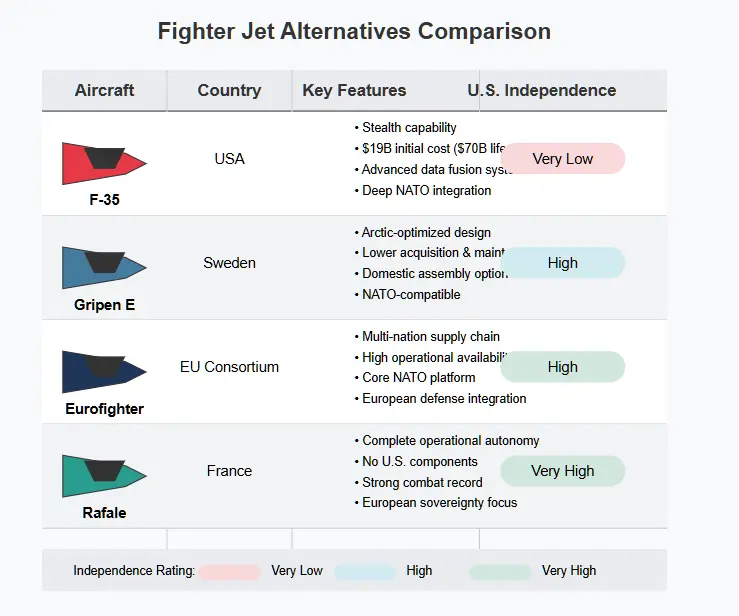

Canada’s $19 billion commitment to procure 88 Lockheed Martin F-35 fighter jets is now under active reconsideration, marking a potential shift away from U.S. defense procurement dominance. This review comes in the wake of Portugal’s sudden cancellation of its F-35 acquisition, a move driven by concerns over cost, geopolitical risks, and excessive dependence on the U.S. military-industrial complex.

While Canada has not formally withdrawn from the F-35 program, internal discussions within the Department of National Defence (DND) and Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government indicate a growing interest in non-American alternatives, particularly from European manufacturers.

The F-35 acquisition, first negotiated under previous administrations, has long been a contentious issue within Canadian defense circles. While the aircraft remains a cutting-edge, stealth-capable multi-role fighter, several factors have prompted reconsideration, including:

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and DND are now weighing several non-American fighter aircraft as potential replacements for the F-35. The leading alternatives include:

While each of these alternatives presents advantages over the F-35, the final decision will depend on broader strategic considerations, including NATO interoperability, supply chain integration, and economic benefits.

A Canadian withdrawal from the F-35 program would represent a major break from traditional U.S. military procurement, with several key implications:

1. Decoupling from Lockheed Martin and U.S. Military Control

Lockheed Martin has historically exercised significant influence over Canada’s fighter jet capabilities, including its role in NORAD and NATO air defense operations. If Canada opts for a non-U.S. aircraft, it will gain greater control over maintenance, upgrades, and mission planning, reducing its dependence on American military approvals.

2. Strengthening Defense Ties with Europe and Sweden

A pivot to Saab, Dassault, or Eurofighter consortium partners would deeply integrate Canada into European defense networks, strengthening non-U.S. military cooperation. This shift aligns with Canada’s broader effort to diversify its defense relationships, particularly as tensions with the U.S. continue to escalate under Trump’s 2025 administration.

3. NATO Coordination and Interoperability Challenges

The F-35 is deeply embedded within NATO air force operations, meaning a departure from the program would require adjustments to alliance-wide military planning. However, NATO is not exclusively reliant on U.S. air power, and multiple European partners operate Typhoon, Gripen, and Rafale jets alongside F-35 squadrons.

While some interoperability concerns exist, European fighters are already fully integrated into NATO’s air defense architecture, meaning a transition would not significantly hinder Canada’s ability to participate in joint missions.

Despite the growing momentum toward alternative aircraft, several risks remain that could complicate Canada’s ability to fully exit the F-35 program:

Canada’s reconsideration of the F-35 fighter jet program is more than just a procurement decision—it is a strategic inflection point that could determine the future of Canadian military autonomy.

This decision will reverberate beyond Canada’s fighter jet fleet, shaping its broader approach to military procurement, NATO participation, and U.S. defense cooperation in the coming decade.

✔ Will Canada formally exit the F-35 program, or will it attempt to renegotiate terms with Lockheed Martin?

✔ Will Canada announce a formal fighter competition, or will it proceed with direct negotiations with European manufacturers?

✔ How will the U.S. react to Canada’s reconsideration, and will Washington use trade or diplomatic leverage to pressure Ottawa into maintaining its F-35 commitment?

✔ Will European defense firms offer domestic assembly to strengthen Canada’s aerospace sector, increasing the political feasibility of an F-35 alternative?

The final decision on Canada’s next-generation fighter aircraft will determine whether the country continues its reliance on U.S. military technology or pivots toward a more independent, European-backed defense strategy.

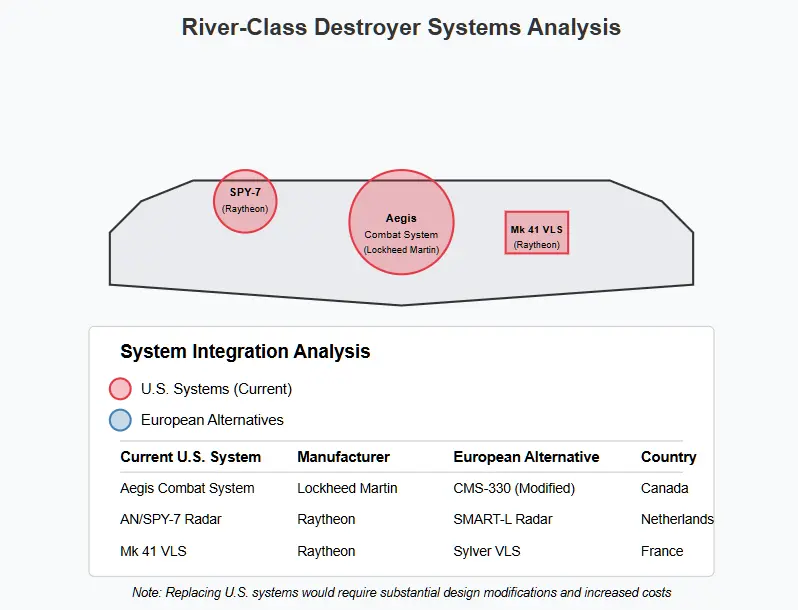

In March 2025, Canada awarded Irving Shipbuilding (Halifax) an $8 billion contract to begin construction of the first three River-class destroyers, marking the latest phase in Canada’s naval modernization program. This project—originally designated under the Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC) initiative—is set to replace Canada’s aging fleet of destroyers and multi-role frigates with a highly advanced, multi-mission warship class.

While the River-class destroyers are being built domestically, the design and core combat systems remain heavily dependent on U.S. military technology, raising concerns about Canada’s ability to maintain operational sovereignty. The destroyers will be equipped with the Lockheed Martin Aegis Combat System, the AN/SPY-7 radar (Raytheon), and Mark 41 Vertical Launch Systems (VLS) (Raytheon)—all of which firmly lock Canada’s naval capabilities into the U.S. military-industrial ecosystem.

This procurement structure effectively ties Canada’s future naval operations to U.S. defense contractors, despite Ottawa’s broader efforts to diversify military partnerships with European and Australian firms. The question now is whether Canada can modify the River-class destroyers to include non-American systems, or if this contract represents a point of no return.

The River-class destroyer program is Canada’s largest-ever naval procurement, shaping the Royal Canadian Navy’s (RCN) capabilities for the next 40 years. The continued reliance on American-designed systems raises multiple strategic and operational concerns, particularly in the context of U.S.-Canada relations, NATO interoperability, and Canada’s growing push for military autonomy.

Despite the current procurement structure, there are still pathways for Canada to reduce U.S. defense dominance within the River-class program. The Combat Management System (CMS-330), developed by Lockheed Martin Canada, theoretically allows for the integration of non-U.S. weapons and sensors, though this would require additional modifications.

Potential European alternatives include:

Integrating these systems would require:

✔ Modifying ship design to accommodate different weapon interfaces

✔ Overcoming contractual restrictions favoring Lockheed Martin and Raytheon

✔ Re-evaluating long-term interoperability with U.S. and NATO forces

While these alternatives are technically feasible, Canada would need to politically justify the additional costs and potential delays associated with breaking away from an all-American system architecture.

If Canada proceeds without modifications, the River-class destroyers will effectively cement U.S. strategic control over Canadian naval warfare capabilities, carrying several long-term consequences:

1. Reinforced Dependence on U.S. Defense Contractors

The decision to integrate U.S. combat systems locks Canada into the American defense ecosystem for decades. Future upgrades, missile purchases, and software enhancements will require U.S. approval, limiting Canada’s ability to independently modify or enhance its naval fleet.

2. Limited Policy Flexibility in Conflicts Involving U.S. Adversaries

Since Aegis and SPY-7 are core components of U.S. global missile defense, these destroyers could be automatically linked into U.S.-led operations against adversaries like China and Russia. If Canada wishes to remain neutral in a U.S.-China or U.S.-Russia confrontation, its ability to do so may be compromised by pre-integrated American systems.

3. Future Political and Industrial Constraints

By tying Canada’s naval power to American technology, the government risks limiting future procurement choices. If Canada later decides to shift toward European or indigenous naval programs, it may face:

The River-class destroyer program is not yet an irreversible commitment to an all-American warship, but the window for integrating alternative systems is closing rapidly.

✔ Short-Term Adjustments Still Possible

✔ Long-Term Dependence on U.S. Defense Firms Likely

✔ Strategic Implications for Canada’s Defense Autonomy

The River-class destroyer program represents both an opportunity and a risk for Canada’s naval future. While these warships will provide the Royal Canadian Navy with cutting-edge multi-mission capabilities, they also risk entrenching U.S. control over Canada’s military operations for decades to come.

Canada still has an opportunity to integrate non-American weapons and sensors, but time is running out. If no changes are made, these destroyers will cement U.S. strategic dominance over Canada’s naval forces, limiting future defense autonomy.

✔ Will Canada seek last-minute modifications to integrate non-U.S. radar, missiles, or weapons systems?

✔ How will U.S. defense contractors respond if Canada attempts to modify the current procurement contract?

✔ Could this destroyer program set a precedent for future Canadian naval acquisitions, making U.S. dependence permanent?

✔ Will Canada continue its trend of diversifying military suppliers, or is the River-class program a sign of deeper U.S. integration?

The next few months will determine whether Canada’s naval modernization strengthens its sovereignty—or further entrenches U.S. control over its military operations.

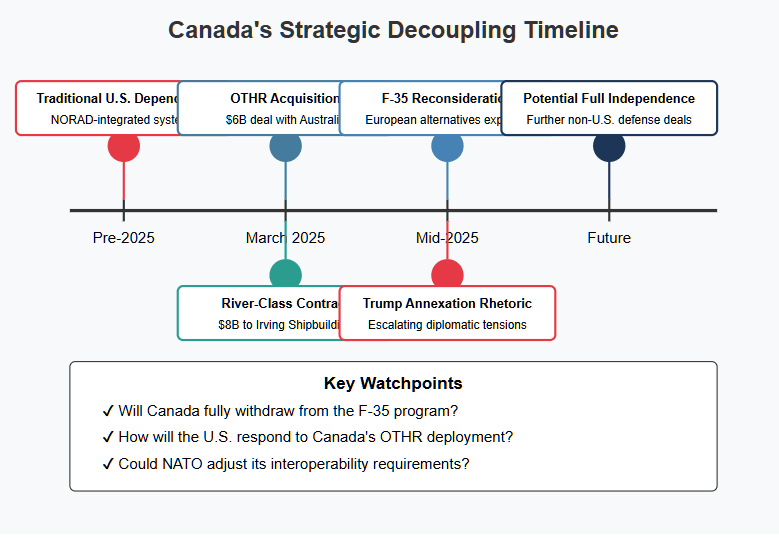

Canada’s recent defense procurement decisions signal a deliberate effort to diversify its military partnerships, reducing its long-standing reliance on U.S. defense technology. The Over-the-Horizon Radar (OTHR) acquisition from Australia, the reconsideration of the F-35 program, and the potential for integrating non-American systems into the River-class destroyers all point toward a broader shift in Canada’s strategic posture.

This realignment is driven by geopolitical necessity, economic considerations, and the evolving nature of U.S.-Canada relations, particularly as Trump’s administration continues to threaten Canadian sovereignty. By securing alternative defense partnerships with Australia and European allies, Canada is working to insulate itself from U.S. political volatility and defense leverage.

While the shift is not yet a full-scale departure from American military integration, it represents the first major effort in decades to assert a more independent national defense policy.

1. Trump’s Annexation Rhetoric and Growing U.S. Political Volatility

Since returning to office in 2025, Donald Trump has openly suggested that Canada should be annexed into the United States, initially framing the statement as a trade negotiation strategy but later repeating it in policy discussions and public rallies. While dismissed by some as rhetorical excess, the Canadian government has taken the threat seriously, recognizing that U.S. policy under Trump is unpredictable and increasingly hostile.

With Canada’s Arctic security interests diverging from U.S. priorities, maintaining a fully U.S.-integrated defense structure leaves Ottawa vulnerable to American political leverage. The OTHR acquisition from Australia and the reconsideration of the F-35 program directly reflect concerns over U.S. reliability as an ally.

2. Strengthening Alternative Defense Partnerships

To offset its traditional dependence on U.S. military systems, Canada is expanding its relationships with Five Eyes allies and European defense firms, ensuring greater control over procurement and operational sovereignty.

Key initiatives include:

✔ The Australia-Canada Over-the-Horizon Radar partnership, marking Canada’s first independent Arctic surveillance system without U.S. oversight.

✔ A potential fighter jet procurement shift toward Saab (Sweden), Dassault (France), or Eurofighter (UK/Germany/Italy/Spain), reducing Lockheed Martin’s control over Canada’s air force capabilities.

✔ Exploring European weapons integration into the River-class destroyers, limiting U.S. control over Canada’s naval fleet operations.

By broadening its defense supply base, Canada is reducing its exposure to American political instability and ensuring that future governments retain more flexibility in defense decision-making.

3. The Need for Industrial and Technological Sovereignty

Canada’s defense industry has been historically dependent on U.S. technology transfers, which has often resulted in restricted access to critical systems and limited domestic production capability. By pursuing defense procurement agreements that include domestic manufacturing, Canada is attempting to rebuild its aerospace and shipbuilding sectors, reducing the outsourcing of strategic defense capabilities to American firms.

For example, Saab has offered to assemble Gripen E fighter jets in Canada, a proposal that Lockheed Martin has refused to match with the F-35. If Ottawa proceeds with a non-American fighter jet purchase, it would signal a major industrial shift, strengthening Canada’s domestic defense production capabilities while reducing U.S. influence.

Canada’s defense realignment is not just theoretical—it is already being implemented. Several major procurement decisions exclude U.S. involvement, breaking long-standing patterns of military reliance.

Each of these defense pivots signals a shift toward greater Canadian control, ensuring that future military operations are not dictated solely by U.S. interests.

While Canada’s gradual break from U.S. military reliance offers long-term strategic advantages, it also presents short-term risks that must be managed carefully.

1. Potential U.S. Retaliation: Economic and Diplomatic Pressure

The U.S. military-industrial complex holds enormous influence over Canada’s defense policy, and any efforts to reduce American integration will likely be met with economic and diplomatic pushback.

✔ The U.S. could impose trade restrictions on Canadian defense exports, impacting domestic suppliers.

✔ Washington could threaten intelligence-sharing limitations within NORAD and Five Eyes.

✔ Trump’s administration could tie trade negotiations to military procurement commitments, forcing Canada to remain dependent on American systems.

2. NATO Coordination and Interoperability Issues

Canada remains a core NATO member, and moving away from U.S.-centric procurement raises questions about operational compatibility.

✔ The F-35 remains a dominant NATO air power asset, and withdrawing from the program could complicate alliance-wide military planning.

✔ While European fighter jets and naval systems are NATO-compatible, they require modifications and integration efforts, which could delay procurement timelines.

✔ The OTHR system’s independence from NORAD raises the question of how Canada will share Arctic intelligence within NATO without U.S. oversight.

These interoperability concerns are manageable, but they require deliberate planning and stronger European defense partnerships.

3. Logistical and Supply Chain Adjustments

A rapid transition away from U.S. defense systems would require:

✔ New maintenance and logistical networks for European or Australian platforms.

✔ A retraining process for Canadian Armed Forces personnel operating non-U.S. equipment.

✔ Strategic investment in domestic industrial capacity to support non-American defense programs.

While these transitions will incur short-term costs, they offer long-term resilience and independence from U.S. defense policy shifts.

Canada’s progressive shift away from U.S. military dependence is now firmly underway. While it is not yet a full break from American defense systems, the OTHR acquisition, F-35 reconsideration, and naval procurement shifts indicate a clear effort to establish greater operational autonomy.

✔ If Canada continues this trajectory, it could fully integrate European and Australian defense technologies, ensuring greater resilience against U.S. political instability.

✔ If Canada delays or reverses course, it risks remaining trapped within a U.S.-controlled defense structure, limiting policy flexibility and national sovereignty.

The next decade will determine whether Canada solidifies its military independence or remains within the American defense sphere.

✔ Will Canada finalize a fighter jet contract with a non-U.S. manufacturer, formally breaking from Lockheed Martin?

✔ How will Washington react to Canada’s Over-the-Horizon Radar acquisition and exclusion of NORAD from Arctic surveillance?

✔ Will Canada move to integrate European weapons into the River-class destroyers, or will the U.S. military-industrial complex block such efforts?

✔ Could Canada strengthen defense ties with the UK, France, Germany, and Sweden to further distance itself from U.S. reliance?

Canada has crossed a threshold in military autonomy. The only question now is how far Ottawa is willing to go in its break from U.S. control.

Canada’s progressive shift away from U.S. defense dependence is no longer speculative—it is actively happening. From the OTHR acquisition with Australia to the reassessment of the F-35 program and the potential modification of the River-class destroyers, Canada is strategically maneuvering to regain greater control over its military capabilities.

This transition is being driven by fourkey forces:

✔ Geopolitical volatility, particularly Trump’s 2025 annexation rhetoric, which has forced Ottawa to reconsider the risks of military reliance on the U.S.

✔ American interference in Canadian domestic affairs including the 2025 Federal Election as well as its funding of the Maple MAGA movement as a fifth column in Canadian society.

✔ Economic and industrial independence, as Canada seeks to strengthen its domestic defense industry rather than serving as an extension of the U.S. military-industrial complex.

✔ Operational sovereignty, ensuring that Canada can engage in military planning, intelligence-sharing, and defense decisions without needing U.S. approval.

While this shift is not yet a full decoupling, the precedents being set today will determine Canada’s long-term defense trajectory.

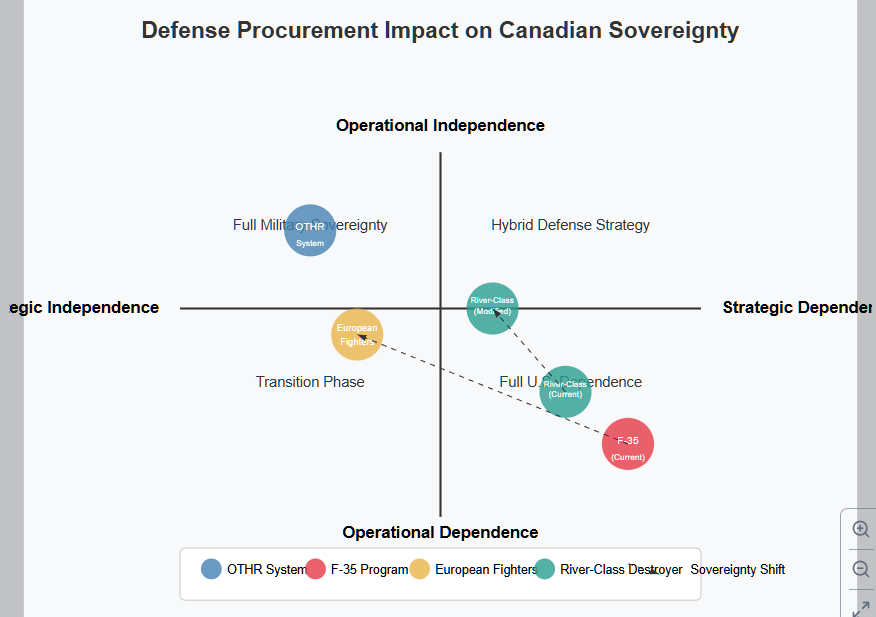

As Canada moves forward with its procurement decisions, it will likely fall into one of three strategic scenarios in the coming decade:

1. Full Military Sovereignty (Break from U.S. Defense Integration)

Implications:

✔ Canada becomes one of the most strategically independent military forces in NATO.

✔ U.S. retaliation is highly probable, potentially in the form of economic or intelligence-sharing restrictions.

✔ Canada must invest heavily in domestic defense infrastructure to compensate for the loss of U.S. supply chains.

2. A Hybrid Defense Strategy (Gradual U.S. Decoupling with Selective Integration)

Implications:

✔ Canada retains flexibility in defense procurement while still maintaining ties with U.S. networks.

✔ Limited U.S. retaliation is likely, but Ottawa avoids major diplomatic confrontations.

✔ Canada still faces some reliance on U.S. supply chains, leaving vulnerabilities in future conflicts.

3. Reversion to Full U.S. Defense Dependence (Status Quo Continuation)

Implications:

✔ Canada avoids diplomatic and economic retaliation from the U.S..

✔ Full interoperability with U.S. and NATO operations is maintained.

✔ Canadian defense policy remains subject to U.S. political shifts, reducing military autonomy.

The next 12-18 months will determine how far Canada is willing to go in its defense realignment. Several critical decisions remain that will shape the country’s military sovereignty for the next 40 years:

✔ Will Canada formally exit the F-35 program and select a non-U.S. fighter jet alternative?

✔ How will Washington react to the Over-the-Horizon Radar (OTHR) acquisition and Canada’s exclusion of NORAD from Arctic surveillance?

✔ Will Canada modify the River-class destroyer program to integrate European radar and weapons systems, or will it remain fully dependent on U.S. combat systems?

✔ Could Canada strengthen defense ties with the UK, France, Germany, Sweden, and Australia to further reduce U.S. leverage?

✔ Will the U.S. retaliate economically or diplomatically against Canada’s defense diversification efforts?

Canada’s military independence is no longer theoretical—it is actively being pursued. Whether through the Arctic surveillance program, the fighter jet reassessment, or the naval procurement strategy, Ottawa is deliberately moving away from automatic alignment with U.S. defense planning.

However, the pace and extent of this transition remain uncertain. Canada must now decide whether it will fully commit to a sovereign military strategy, or if it will settle for partial decoupling while maintaining elements of U.S. defense reliance.

Regardless of the final outcome, one fact is clear:

Canada has entered a new era of defense policy, and the choices made in the coming months will define its national security strategy for decades to come.

[…] Nordic Baltic 8) to further secure the alliance’s northern and western flanks, including through Canada’s unprecedented investments in over-the-horizon radar, submarines, in aircraft, and boots on the ground, […]

[…] Expanding military partnerships with Canada, the UK, and Australia – from which Canada recently purchased a new Over-The-Horizon Radar System. […]