Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

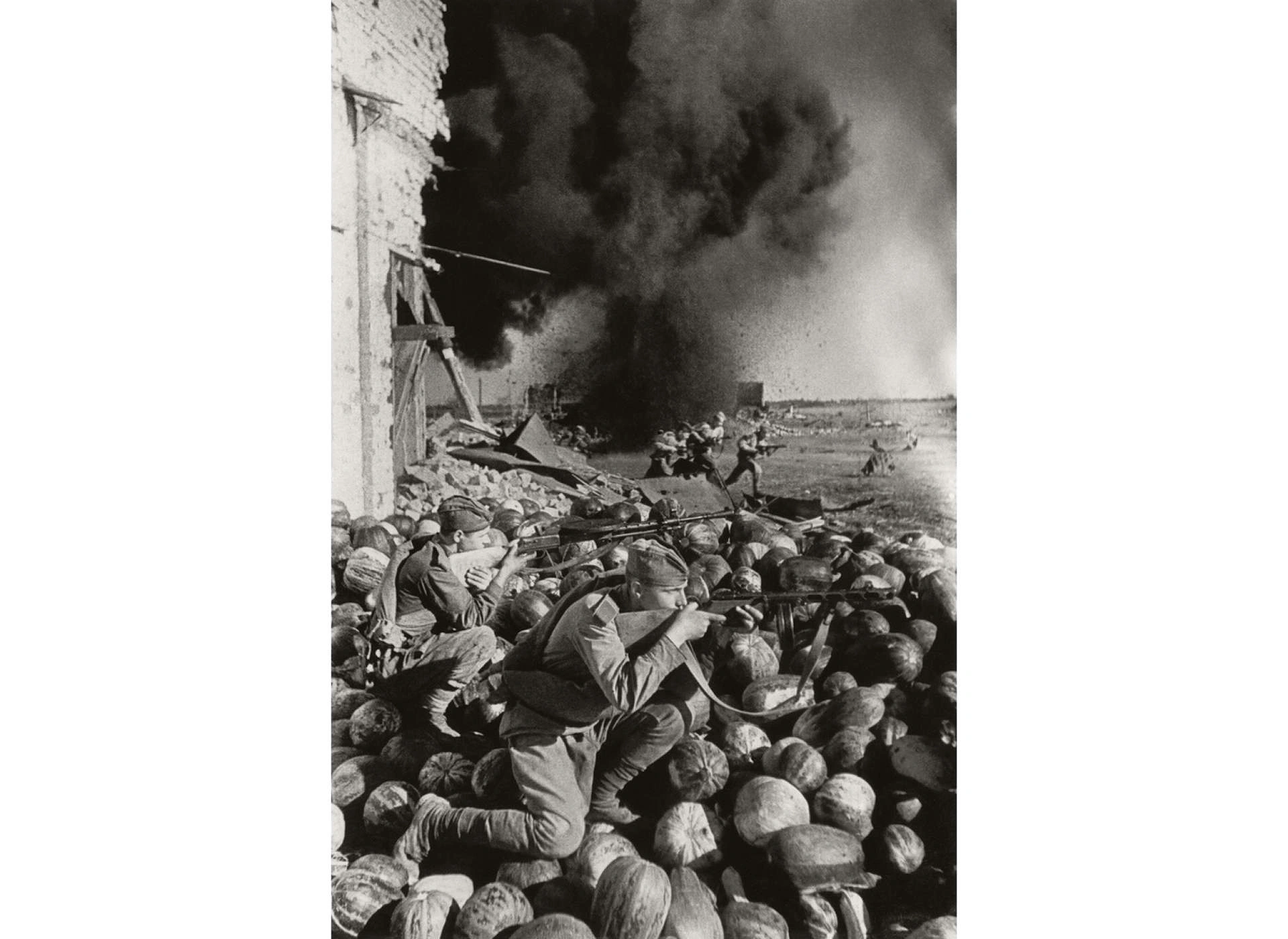

Seeking to understand the barbarism and brutality of the Second World War’s Eastern Front, this analysis examines the human, psychological, social, and military facets of the battles which occurred on this front. Beginning with an overview of its human elements, the analysis argues that widespread conscription was a significant facet in explaining the poor military capacities of the troops fighting on this front. Turning to psychological elements, the analysis argues that, as the conflict dragged on, the German soldiers, who expected a rapid endgame, lost significant motivation. With regards to social elements, the analysis further proposes that the length of the conflict allowed for widespread and holistic mobilization throughout Russian society, and thus allowed the state to confront the Reich’s far more potent war machine. Finally, examining the military facets of the battle, the analysis argues that, because the Germans ended up fighting a war of attrition, rather than their intended war of maneuver, the Russians were able to thoroughly mobilize, from a social point-of-view, and thus a create a context of complete and holistic resistance against the Germans.

On this basis, the analysis proposes that the massive human suffering which existed on the Eastern Front, in a context where an intended war of maneuver became one of attrition, can be explained on the basis of a combination of political miscalculation and human resilience. With regards to the former, the German high command’s vision of a two front war was overly optimistic, and failed to countenance the resolve of the Russian forces. With regards to the latter, the many Russian conscripts who defended their homeland in this conflict, literally fighting for their homes and lives, were capable of engaging the Soviets in a stalemate, and thus turning a fait accompli into a bloody struggle for every inch of territory. Thus, in the end, the barbarism of the Eastern Front is a direct corollary of these political and human variables, and must be understood in this context rather than as a product of any single monolithic factor.

At base, understanding the Eastern Front requires understanding the men who fought its battles. In this respect, Schulte proposes that significant differences existed between the German and Russian soldiers. While the former had often been trained significantly, even in the case of conscripts, Russian soldiers were far more likely to be conscripted members of civilian militias who lacked any significant form of military training. This said, however, this does not imply a lesser overarching troop quality on the Russian side. While the Germans were far better trained, and had been subjected to longitudinal propaganda-based indoctrination, the Russians were motivated by the very real and tangible concerns associated with an invasion of their homelands. Thus, and in spite of the Germans’ superior training, the Russians were able to resist because of the esprit-de-corps which emerged from the stakes of their fight.

Moving forward, it is also important to consider that many of the men who fought on the Eastern Front were not the types of professional soldiers who fight wars today. Rather, and in line with the work of Axworthy, a wide portion of these soldiers were nothing more than conscripted peasants. While this situation was certainly more ubiquitous on the Russian side than on the German one, both armies were largely made up of farmers and factory workers who did not have the training required to fight a technologically-predicated war like WWII. Thus, the Germans had a significant advantage in terms of training, and in terms of the skill of their personnel. This said, however, the fact that most of the Soviet troops were fighting to protect their homes, even though they were conscripted, gave them an additional and potent source of motivation in pushing back the Germans.

Turning to more psychological variables, declining German motivation became a significant factor as the war dragged on. While German indoctrination and training levels originally provided a salient level of motivation at the war’s beginning, especially when combined with the ubiquitous German belief that the victories of the Western front would rapidly repeat themselves on the Eastern one, German motivation suffered immensely as the vagaries of the Eastern Front came into place. Thus, as the brutal Russian winter took hold, food became scarce, and it became clear that the Front was becoming the location of a war of attrition, even elite German units began to doubt the wisdom of their political leaders’ decision to launch a two-front war.

On this basis, understanding the degradation of motivation which the Germans suffered on the Eastern Front, a psychological variable deeply affected by the material conditions of the war, provides significant understanding of the degradation in efficiency which the Germans suffered over the course of the war. Thus, as the Germans saw that their superior tactics and combined arms approach was not a panacea against the solid Russian defenses, they began to experience severe doubts about the war itself. In this context, where Russian motivation was growing, as it became evident that the Soviets were overstretched, German morale became the mirror opposite of that of the Russians. Moreover, as the War in the West gradually shifted against the Germans, and the Russians began to slowly push the Germans out of their homeland, repeated casualties led to fresh, inexperienced, and unmotivated German troops to be deployed to the front lines. On this basis then, it is truly no surprise that the Germans were unable to longitudinally maintain their initial momentum, in terms of motivation, when the war indeed became a stalemate.

Alongside this longitudinal German decrease in motivation, the length of the battle on the Eastern Front, as a result of early Russian delaying actions, allowed the Soviet Union to mobilize its entire society so as to fight the war. Thus, while the earliest stages of the war only saw militia members and regular troops fight in the conflict, its middle and latter stages bore witness to the emergence of a wide variety of militias and conscripts, as well as to a myriad of women who fought alongside their brothers, husbands, and fathers. Thus, as German resources became stretched, because of the two front nature of their war, the Russians were able to mobilize even more significantly, and ultimately engage in a form of total war which was anathema to Germany’s objectives.

In this context, the mobilization of Soviet society into total war must be understood within the framework of the experience of the typical German soldier on the Eastern Front. While the war’s early days were met with anticipation and optimism, food and material shortages, along with the harsh German winter, brought about a situation in which the typical German soldier was experiencing hunger, pain, and frustration with the war effort. With the high command mostly focused on the war in the West, and notably the quixotic bombing of Britain, resources which should have been sent to the East were instead wasted on a likely unwinnable Western campaign.

Moreover, it is worth noting that, as the war went on, the combat performance and effectiveness of the Red Army increased dramatically. While the early years of the war bore witness to a relatively “rag-tag” bunch of Russian irregulars fighting alongside the country’s professional soldiers, conscription and training led to the formation of a far more potent fighting force. Additionally, as Russia’s industrial might was turned to the production of arms, along with Western support, the country soon came close to matching Germany’s technological innovations. Additionally, the Russian high command refined new strategies, implemented new training protocols, and ultimately built a force which, while not as saliently trained as the Germans, was capable of engaging the former on its own terms.Because the Russians fought a delaying action, they were capable of increasing the time horizon of the German invasion’s endgame, and of thus turning their latent sources of power into actual force.

What is perhaps even more interesting about the incredibly bloody campaign on the Eastern Front is the fact that it was premised on a war of attrition rather one of maneuver. With Liulevicius noting that Germany had developed the Blitzkrieg tactics which it used on the Western Front so as to preclude a recurrence of the bloody stalemate-type battles of WWI, Germany’s intentions regarding the Eastern Front did not unfold as planned. While the Germans initially intended to make use of similar Blitzkrieg tactics in their forays into Eastern Europe and Russia, the massive size of the contemporaneous Soviet Army led the German advance to degrade into a land war, and produce the type of war of attrition, analogous to the battles which occurred at places like the Somme, during battles like the one which occurred at Stalingrad.[8]

With this, the massive human cost of the War on the Eastern Front can be understood, according to Lulevicius, as a strategic, operational and tactical failure for the Germans. While the latter succeeded in wreaking havoc across the Russian countryside, fighting a form of total war in which many Russian agricultural and industrial resources were destroyed, the Germans were incapable of fighting the war on their own terms. While their significant advantages in armor and air power should have guaranteed them a swift and positional victory on the Eastern Front, the tenaciousness of the Russian forces, combined with the sheer number of infantry conscripts which the country was capable of deploying, produced a context in which Germany’s tanks and airplanes were brought to a stalemate by well-entrenched Russian forces.

Thus, in understanding the misery of the Eastern Front, and the sheer human misery which occurred there, for both sides, it is imperative to understand that the conflict which was fought there was not the one which the Germans originally intended. Rather, because of the potency of Russia’s defensive abilities, the conflict quickly turned away from the variety expected and planned for the by German high command, and shifted towards a context in which Germany’s military advantages, technologically-premised in nature, were rendered moot by the resilience and local knowledge of Russian forces. Thus, while German interwar military innovation may have led the country’s high command to expect anything but a recurrence of the patterns of 1914-1918, the Eastern Front saw these entrenched once again, causing both great misery to the men on the battlefields, and significant degradation to the pace of Germany’s conquest.

With these four sets of variables in mind, it is no surprise that the war on the Eastern Front bore such a horrible human toil. Combining such significant elements as hunger and cold on the German side with a desperate attempt to protect one’s homeland on the Russian one, the context showed all of the hallmarks which one would expect from the bloodiest of battles. Thus, while the war on the Western Front was relatively rationalized during the early years of the conflict, the German military’s intrusion into Russia rapidly took on the characteristics which we would expect to see in a quagmire. With an incredibly long supply train that could not support the troops deployed, along with a decaying overarching sense of morale, the Germans were doomed once the Soviets were able to halt the initial maneuver-based engagement, and force the Germans to face off against them in set-piece battles like the one which occurred at Stalingrad.

Additionally, much of the massive bloodshed and misery which occurred on the Eastern Front appears to have resulted from the concomitant resilience of the Russian people, and of the miscalculation of the German high command. While early indications from the Western Front suggested that the combined arms approach of Blitzkrieg was a panacea against the lesser-armed forces of France and Belgium, the Russians succeeded in developing operational, strategic and tactical counterweights to Germany’s strategies. Additionally, because the Russians knew the land on which they were fighting so well, because they were often local militia members, the Russians had intangible qualitative advantages over their Russian foes. On this basis, understanding the protracted war of attrition which the Red Army succeeded in lulling the Wehrmacht into requires a broader understanding of the individual, social, psychological and military dimensions of the conflict.

With this, the bloodshed of the Eastern Front did not occur in a vacuum. Rather, and within the broader context of the war, it embodies the massive overstretch which the Germans subjected themselves to when they decided to context Europe on more than one front. Tangibly, and given the relatively small size of the German population and its production capabilities, the country was doomed from the beginning. While the counter-factual of the Russians having not succeeded in repelling the initial invasion may provoke a thought experiment in which German resources could have won the day, the scarcity of the former call into question the possibility that the Eastern Front could have ever been won. Indeed, because this overstretch was inherent to the Germans’ war plans, any success in resistance, on the parts of the Russians, would have been germane to creating the quagmire which dragged the Germans down on the Eastern front. Thus, looking at the Eastern Front within the broader context of the war, and assuming that successful Russian resistance was at least somewhat inevitable; Germany’s multi-front plan was doomed from the start.

In the end, the experiences of German and Russian troops, on the Eastern Front, were remarkably similar. With both sides engaged in a battle which had no obvious and linear form of victory, the quagmire of the conflict produced a sheer degree of misery, from casualties, the cold and hunger, which was salient on both sides. Thus, even as the Germans could claim initial success in invading Russian territory, and in creating a fait accompli on the Eastern Front, the resilience of the Russians was capable of derailing these plans. Moreover, it becomes clear that German overconfidence, in terms of the doctrine of Blitzkrieg, was also elemental to precluding Germany’s ability to win the war. When an entire strategic framework is degraded by supply train difficulties and increasingly poor morale, it is incredibly difficult to conceive of a given side in a war being able to successfully achieve its strategic objectives. Moreover, given the context of scarcity in which the Germans fought, because of the country’s relatively small size and population, it is apparent that its operations on the Eastern Front never truly had a chance to succeed in earnest.

On this basis, characterizing Germany’s operations on the Eastern Front as being quixotic appears to be historically responsible. While the same characterization is applied to the bombing of Britain earlier in this analysis, the reasoning behind such a characterization is predicated on the simultaneity of Germany’s military endeavors. While each might have succeeded in isolation from the others, Germany suffered from tremendous overstretch which completely degraded its military capabilities. In such a context, the problematic logic of this situation is that Germany would have also been doomed, because of contemporaneous alliance patterns, if it had not undertaken these simultaneous actions. As such, Germany’s geostrategic position likely doomed its war on the Eastern Front, as well as elsewhere, from the beginning of the conflict.

Axworthy, Mark. “Peasant Scapegoats to Industrial Slaughter: The Romanian Soldier at the Siege of Odessa.” In Time to Killl: The Soldier’s Experience of War in the West, 1939-1945, edited by Paul Addison and Angus Calder. New York, NY: Pimlico, 1997.

Erickson, John. “Red Army Battlefield Performance, 1941-1945: The System and the Soldier.” In Time to Kill: The Soldier’s Experience of War in the West, 1939-1945, edited by Paul Addison and Angus Calder. New York, NY: Pimblico, 1997.

Forster, Jurgen. “Motivation and Indoctrination in the Wehrmacht, 1933-1945.” In Time to Kill: The Soldier’s Experience of War in the West, 1939-1945 edited by Paul Addison and Angus Calder. New York, NY: Pimblico, 1997.

Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel. War Land on the Eastern Front.New York, NY: Cambridge University Press 2000.

Murray, Williamson, and Allan R. Millet. A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War.Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001.

Pennington, Reina. “Offensive Women: Women in Combat in the Red Army.” In Time to Kill: The Soldier’s Experience of War in the West, 1939-1945, edited by Paul Addison and Angus Calder. New York, NY: Pimlico 1997.

Schulte, Theo J. “The German Soldier in Occupied Russia.” In Time to Kill: The Soldier’s Experience of War in the West, 1939-1945, edited by Paul Addison and Angus Calder. New York, NY: Pimlico, 1997.