Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

There is a peculiar kind of peace that descends when you realize no one is steering the ship — and that the iceberg has already filed a permit.

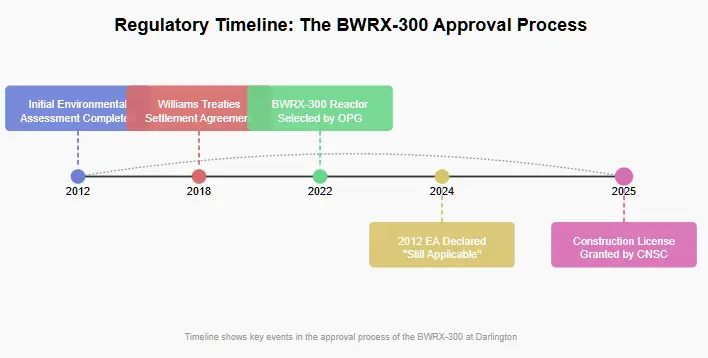

On April 4, 2025, the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) announced its decision to grant Ontario Power Generation (OPG) a licence to construct a BWRX-300 small modular reactor at the Darlington New Nuclear Project (DNNP) site in Clarington, Ontario. The licence is valid until 2035, which is coincidentally just long enough for a new generation of bureaucrats to disown the decision.

The CNSC was, in its own words, “satisfied” that all legal obligations had been met. It concluded — without detectable irony — that a 2012 environmental assessment was still applicable to a nuclear reactor design selected a decade later, commercialized by a different vendor, and never before constructed anywhere on Earth. It was also satisfied that Indigenous consultation obligations had been fulfilled, a conclusion reached without the need for new consent, or apparently, conversation. It even cited a $167 million “financial guarantee” as evidence of prudence — a figure that, as clarified during pre-publication review by Theresa McClenaghan, Executive Director and Counsel at the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA), applies only to the as-built stage: that is, prior to fueling, operation, or contamination risk. In plain terms, the money covers unfinished concrete — not radioactive fallout. Safety, like consultation, like assessment, is promised — but never actually secured.

In the weeks leading up to the Darlington BWRX-300 reactor approval, the public hearing resembled what one might generously call stakeholder theatre. Critics were acknowledged in the way one acknowledges rain on a wedding day: politely, and with no intention of altering the schedule.

To the untrained eye, this might appear to be a landmark in Canadian energy innovation. In truth, it’s something far more ambitious: the licensing of a hypothetical machine using legacy paperwork and moral force. Like issuing a building permit for a lighthouse based on blueprints for a gazebo.

What follows is not an exposé in the traditional sense — there is no smoking gun, only a paper trail arranged like a performance piece. It is a story about confidence: in process, in precedent, in the idea that regulation itself can carry meaning long after it ceases to exert control. The CNSC calls this “trust.” Others might call it heat without light.

Either way, the reactor has been approved. Whether it will be built, whether it will work, and whether it will be safe — those are questions for the next licence. This one merely clears the land, metaphorically and otherwise.

One wonders, as the backhoes warm up beside Lake Ontario, whether the future is truly being built — or simply waved through.

At the center of the Darlington BWRX-300 reactor approval lies a curious object — or rather, the promise of one. The BWRX-300 is what’s known in the nuclear industry as a “first-of-a-kind” reactor. In practical terms, that means it exists mostly in engineering renderings, investor decks, and the unfaltering imaginations of its developers at GE Hitachi. It has never been built. It has never been operated. It is, for all intents and purposes, a theoretical construct with a PR team.

This is not, in itself, an indictment. Every reactor design begins as theory. What is unusual — and uniquely Canadian — is that our federal regulator has decided that absence of evidence is an acceptable foundation for a 300-megawatt infrastructure project.

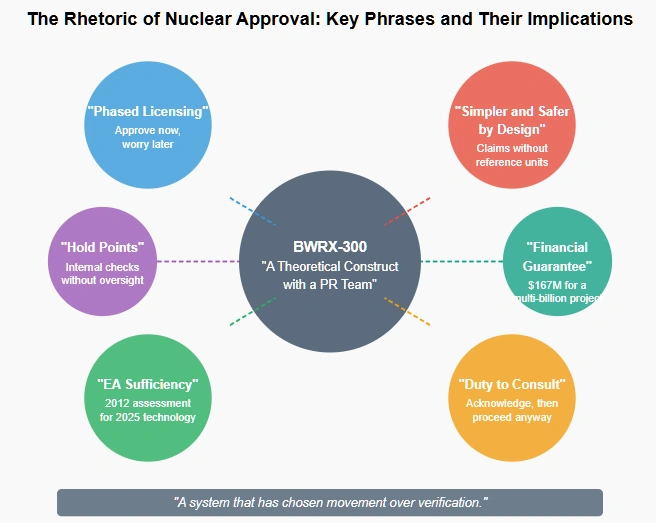

The BWRX-300 is a boiling water reactor — a distant cousin of the older BWR designs deployed elsewhere in the world. Its novelty lies in its “modularity,” a term that suggests convenience, like flat-pack furniture or a subway tile backsplash. GE Hitachi’s website calls it “simpler and safer by design.” Which is true, if one accepts that design is synonymous with performance. It is also, notably, the only reactor technology Canada has ever licensed for construction without a single completed reference unit.

This is licensing by aspiration.

At best, the BWRX-300 is a promissory note. At worst, it’s a high-risk prototype parked beside a major drinking water source. The CNSC has described its approach as “phased licensing,” meaning it has chosen to approve construction activities now, and worry about operational safety later. This process is framed as rigorous. It is, in practice, a polite way of saying: we’ll figure it out as we go.

Canada is not alone in pursuing small modular reactors. The UK is exploring Rolls-Royce designs. The U.S. flirted with NuScale until its price tag ballooned into absurdity and the flagship project collapsed. But few countries have gone quite so far in licensing the unknowable as though it were a known quantity. Fewer still have done so using a decade-old environmental review tailored to other reactor designs.

The BWRX-300 may one day be a marvel of engineering. It may also never materialize at all. The risk is not only technical — it is regulatory, reputational, and political. By approving this design before its maturity, the CNSC has attached the credibility of Canada’s entire nuclear oversight regime to a machine that, for the time being, remains theoretical.

And if it doesn’t work? If something goes wrong? Well, it was only ever Phase 1.

Environmental assessments are meant to protect the future. Canada’s nuclear regulator, with admirable efficiency, has decided they can also be reused to predict it.

The Darlington New Nuclear Project — or DNNP, if one prefers acronyms that sound like logistics firms — was subject to an environmental assessment (EA) completed in 2012. At the time, Ontario Power Generation (OPG) proposed “up to four” new reactors of unspecified design. The Joint Review Panel, operating under the since-repealed Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, examined representative reactor technologies and issued a 290-page verdict: no likely significant adverse environmental effects, provided OPG followed through on its promises.

That was thirteen years ago. The iPhone 4S was cutting-edge. The Kyoto Protocol had just expired. The BWRX-300 — the design now approved for construction — did not yet exist.

And yet, in April 2024, the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission announced that this 2012 EA remained “applicable” to the BWRX-300, requiring no new assessment. This declaration was not based on new fieldwork or a comparative risk analysis. It was simply a statement of administrative belief, issued by the same body tasked with overseeing the license.

In regulatory terms, this is called a “determination of EA sufficiency.” In everyday language, it is time travel with a clipboard.

The logic is elegant in its circularity. The CNSC argues that the BWRX-300 is “not fundamentally different” from the reactor types previously assessed — a phrase so broad it could be applied to virtually any pressurized kettle. That phrase is also undefined in Canadian law. The EA itself never examined passive safety systems, digital instrumentation, or the modular construction methods now being touted as breakthroughs. The BWRX-300 was smuggled through the front door of a decade-old review, as if to say: if it fits the outline, it must be fine.

This maneuver accomplishes several things. First, it shields the project from UNDRIP-aligned consultation triggers, which would be required under a new EA. Second, it prevents Indigenous Nations and public stakeholders from demanding updated cumulative effects assessments — a particularly sensitive omission given the proximity of the existing Darlington Waste Management Facility. And third, it accelerates the licensing timeline by severing safety from scrutiny.

There is a particular genius to it. By declaring the past sufficient, the CNSC has effectively pre-approved the future.

One could argue this is efficient. But efficiency in environmental oversight is often indistinguishable from erosion. EAs are not just procedural artifacts — they are public records of what risks were considered, and what realities were ignored. A document written in 2012 cannot meaningfully address the downstream effects of climate-driven hydrology shifts, nor the interlocking emergencies of energy policy, biodiversity collapse, and cumulative nuclear footprint.

And yet, here we are, breaking ground on a reactor that no one imagined in 2012, with a risk profile no one reviewed, in an ecological moment no one foresaw.

The EA stands. The earth shifts. The timeline remains unchanged.

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission is many things — technocratic, consistent, unshakably confident in its own interpretive frameworks — but above all, it is deeply committed to declaring its duties fulfilled.

In its April 2025 approval of the Darlington BWRX-300 reactor, the Commission stated that it had “fulfilled its constitutional responsibility to consult and, where appropriate, accommodate Indigenous rights.” The phrasing is precise. It echoes Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, while gently sidestepping the harder demands of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDRIPA).

That sleight of language — consult, not consent — is not accidental. It is the cornerstone of what might be called Canada’s polite extractivism: a model in which information is shared, feedback is gathered, and projects proceed exactly as planned.

To understand the dissonance, one must return to the land itself.

The Darlington site sits within the traditional territory of the Michi Saagiig Anishinaabeg, and more formally within the bounds of the Gunshot Treaty (1877–88) and the Williams Treaties (1923). These were not benign agreements. The Williams Treaties extinguished hunting and fishing rights — a decision later declared unjust by federal negotiators and formally addressed in a 2018 Williams Treaties First Nations Settlement Agreement. That agreement included financial compensation, land transfers, and an explicit recognition of rights previously denied.

And yet, in the matter of the BWRX-300, no new treaty consultation process was initiated. Instead, the CNSC leaned on the original environmental assessment from 2012 — conducted before the 2018 settlement, before the passage of UNDRIPA, and before the BWRX-300 was even selected.

This is not merely outdated; it is legally discordant.

Elsewhere in Canada, Kebaowek First Nation is currently suing the Crown over a similar pattern of exclusion — in this case, regarding the siting of the NSDF radioactive waste facility at Chalk River. Their claim is simple: consultation must be current, collaborative, and led by the rights-holders. The CNSC, as a lifecycle regulator, was explicitly named in that case. The same structural issues — outdated EAs, absent FPIC, procedural overreach — are at play in both files.

In response, the Commission offers its usual comforts. It has funded “Indigenous engagement activities.” It hosts public hearings, provides participant funding, shares information. These gestures are framed as trust-building. They are, in effect, institutional theatre — a model where consent is assumed because opposition was acknowledged.

To be clear: there is no public record indicating that any Williams Treaties First Nation provided free, prior, and informed consent for the BWRX-300 reactor. Nor is there any evidence that they were offered a formal veto — a core principle of FPIC. What exists instead is a record of presentations, PowerPoint decks, and regulatory timelines too fast for sovereignty to catch up.

This is not oversight. It is a controlled burn of legal obligation, lit quietly under the cover of “duty discharged.”

Canada’s regulatory regime likes to imagine that the act of consulting is itself sufficient. But consultation without consequences is not a safeguard. It is a ritual — one that performs respect while enshrining power asymmetries.

The CNSC may indeed believe it has fulfilled its responsibilities. But belief is not consent. And silence, especially when manufactured through outdated documents and procedural momentum, is not participation.

Somewhere in the footnotes of this licence is a line that reads like reassurance: that Indigenous engagement will “continue throughout the licence period.” Which is to say: consultation may continue — but only after the decision is final.

To the uninitiated, the language of nuclear oversight can sound reassuringly mechanical. Take, for example, the term “regulatory hold point.” It conjures the image of a firm, unyielding checkpoint — a red light at the edge of risk, not to be crossed without independent validation.

At the Darlington New Nuclear Project, there are three such hold points embedded in the construction licence for the BWRX-300:

These are, on paper, significant milestones. Each one marks a technical and symbolic shift: from theory to structure, from structure to core, from core to activation. Each, we are told, is an opportunity to pause, verify, and confirm that all is as it should be.

But in practice, these hold points are not public checkpoints. They are internal milestones, monitored by the CNSC’s Regulatory Operations Branch — the same branch that recommended the licence in the first place. The Commission itself — the quasi-judicial tribunal with the legal authority to grant or deny licences — does not automatically review hold point removals. Instead, that authority has been delegated to a single executive: the CNSC’s Executive Vice-President and Chief Regulatory Operations Officer.

It is worth pausing here.

This means that once the construction licence is issued, the most consequential safety decisions during early construction are no longer subject to public hearing, independent review, or tribunal oversight. They are operationalized — streamlined in the name of efficiency — and handled by a senior staff member whose job is to keep the project moving, not to scrutinize its existence.

If the licence itself is a green light, then these hold points are simply temporary speed bumps, designed to ensure continuity rather than accountability.

There is nothing illegal about this arrangement. In the logic of lifecycle regulation, it is even considered best practice — a sign that Canada is a “mature regulator” with the tools to manage risk incrementally. But maturity, in this context, also means discretion without transparency.

The public will not see the internal reports that justify hold point removal. There will be no livestreamed tribunal questioning, no transcript, no cross-examination. The operator — OPG — will submit documentation. CNSC staff will review it. The EVP will authorize continuation. The project will proceed.

It is a closed loop. The regulator regulates itself. The brakes exist, but the driver is the same person who installed them.

The Commission’s backgrounder states that these hold points are “essential to verify compliance with regulatory requirements.” What it does not state is who, precisely, will do the verifying — and under what conditions the answer might ever be “no.”

In most regulatory systems, discretion is the exception. In Canada’s nuclear file, it is the rule. And nowhere is that more evident than here: in the quiet moment when oversight becomes internal workflow, and the promise of control is fulfilled by a signature behind closed doors.

Every good performance needs a prop. In the case of the Darlington BWRX-300 reactor approval, that prop is a $167,180,000 financial guarantee — a letter of credit presented as a safeguard, accepted as proof, and filed away like a well-staged security deposit.

The CNSC calls this a “financial guarantee” under the Nuclear Safety and Control Act — a safeguard meant to ensure that if Ontario Power Generation (OPG) walks away from the project, or if the whole thing collapses mid-construction, there will be funds on hand to decommission the site. During pre-publication review of this article, Theresa McClenaghan, Executive Director of the Canadian Environmental Law Association, clarified that the guarantee applies only to the as-built stage — that is, before the reactor is ever fueled. Which is to say: the money is there for unfinished concrete, not radioactive fallout.

This framing — decommissioning for an unfinished, unfueled facility — creates a subtle but devastating loophole. It means the financial guarantee does not cover contamination, criticality events, or long-term remediation costs if the reactor is ever commissioned. In effect, the CNSC has secured a security deposit for a construction site, not a nuclear facility. Should the project be cancelled before fueling, the letter of credit may cover concrete and rebar removal. But once uranium enters the conversation, the guarantee becomes a historical artifact — symbolic, irrelevant, and fiscally useless. What looks like foresight is, in reality, a line item for walking away clean before the real risks begin.

One hundred and sixty-seven million dollars. To secure a first-of-its-kind nuclear prototype, beside a major drinking water source, under a licensing regime built on speculative engineering and procedural faith.

To put that number in context:

And unlike decommissioning funds in other industries — oil and gas, for example — this guarantee is not pooled, not transparent, and not accessible to the public. There is no portal showing how it was calculated. No breakdown of remediation scenarios. No evidence that it accounts for future contamination, fuel failure, or radiological dispersal. It exists as a number, untethered from consequence.

This is not protection. It is performance — a fiscal placeholder that creates the illusion of preparedness while postponing actual responsibility.

It also fits a familiar pattern. Across Canada’s nuclear landscape, cleanup liabilities are treated as accounting footnotes rather than structural obligations. The federal government currently carries more than $16 billion in unfunded radioactive waste liabilities, most of it tied to ghost infrastructure like Chalk River and Whiteshell. These are costs that vanish from licensing files, only to reappear decades later in federal budgets and intergenerational debt.

The BWRX-300 is being licensed under the banner of “learning from the past.” But its financial architecture recycles every oversight that made the past unsustainable. The only difference is the scale — smaller numbers, same erasure.

A letter of credit cannot clean contaminated soil. It cannot evacuate a community. It cannot seal a malfunctioning containment vessel or negotiate bankruptcy clauses with subcontractors. What it can do — elegantly, quietly — is create the appearance of accountability long enough for the next phase to begin.

It is, like so much in the Darlington file, not designed to hold weight. Only to hold questions at bay.

The beauty of a small modular reactor is that almost no one knows what it is. This allows it to become whatever is most useful in the moment: climate solution, economic engine, technological leap, political insulation. Like a Rorschach blot with a billion-dollar price tag, the BWRX-300 is not just a reactor. It is a narrative vessel.

Ask a federal minister what it represents, and you’ll hear phrases like “net-zero future” or “clean baseload.” Ask a provincial energy bureaucrat, and it becomes a hedge against natural gas and interprovincial transmission. Ask GE Hitachi, and it is the leading edge of a global SMR export market, “deployable in the 2020s” — a timeline that has quietly migrated into the 2030s.

Ask the CNSC, and it is a perfectly licensable object. Not because it exists, but because it fits the template.

This semantic flexibility is not a bug. It is the core design feature of Canada’s SMR policy architecture. Unproven technologies are granted rhetorical certainty. Safety is assumed through design intent. Consultation is implied through documentation. Environmental effects are pre-cleared through backward-looking approvals.

The public — excluded from the design, unconsulted on the licensing, and generally unfamiliar with nuclear taxonomy — is invited to treat the BWRX-300 as a symbol of responsible ambition. Clean energy, but engineered. A future you don’t need to worry about.

Even the name participates in the fog. “BWRX-300” is technical enough to seem trustworthy, ambiguous enough to resist public scrutiny. There is no common mental image of it. Unlike wind turbines or solar panels — which can be seen, debated, and contested in local landscapes — the SMR remains placeless, existing only in stylized renderings and animated explainer videos.

This abstract quality allows the project to avoid confrontation. There is no single moment when the public was asked, plainly, “Do you want this reactor?” There is only momentum, and the idea that saying no would be anti-science, or worse, anti-progress.

Media coverage reflects this ambiguity. The phrase “first-of-its-kind” appears frequently, but rarely with follow-up. Few articles mention the lack of a working model. Even fewer note that the environmental assessment is thirteen years old. Instead, reporters quote press releases from OPG, then balance them with quotes from officials who once consulted with OPG.

This is regulatory strategy as semiotics. By the time anyone notices that there is no reactor, no operating precedent, and no safety validation beyond vendor claims, the narrative has already settled.

The BWRX-300 is no longer a project to be evaluated. It is a symbol to be preserved.

And that’s the trick: once a project becomes a metaphor, its risks can be reframed as necessary. Delays are evidence of diligence. Criticism is mischaracterized as obstruction. Every doubt becomes a communication issue, rather than a design flaw.

In that sense, the BWRX-300 is succeeding — not as a reactor, but as a narrative product. It absorbs scrutiny, then reflects back confidence. It exists in a zone of permission: permitted to exist, permitted to proceed, permitted to define itself by what it might become, not what it demonstrably is.

And if the metaphor collapses? If the timeline slips, or the funding dries up, or the project is quietly shelved?

No one will be liable. Because, after all, no one ever promised it was real.

Heat is a funny thing. It moves without shape, registers without presence. It can be traced, but not always felt — until it accumulates.

In its April 2025 decision, the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission gave Ontario Power Generation permission to construct a reactor that does not yet exist, on a site cleared by a decade-old environmental assessment, under a regulatory process so streamlined it barely ripples the surface of public awareness.

On paper, it looks like progress. In motion, it feels like drift. This is what regulatory confidence looks like in Canada: an accumulation of unchecked certainties, carried forward by tone, precedent, and institutional decorum.

Throughout this process, there were no alarms. The project was proposed, assessed (sort of), consulted (allegedly), and approved. Indigenous consent was declared adequate. Safety was declared achievable. Environmental effects were declared unchanged. All without raising a single legal threshold high enough to trigger re-examination.

That’s how you build momentum: not by silencing critics, but by absorbing them into the structure. A hearing was held. Submissions were logged. Comments were acknowledged. And then, quietly, the machine moved forward — not because it answered the questions, but because it outlasted them.

This is the genius of the current regime. It does not deny risk. It disperses it. Across time, across agencies, across footnotes. So that by the time a decision is made, accountability has already left the room.

The BWRX-300 may one day prove safe. Or it may never reach commissioning. Or it may reach commissioning and then fail in some minor, major, or unquantifiable way. These are not predictions. They are the inevitable shadows of a system that has chosen movement over verification.

The CNSC calls itself a lifecycle regulator. What it has regulated here is a lifecycle of belief: from proposal, to approval, to construction — all without ever proving that the reactor in question should exist, here, now, in this place, on these terms.

Trust, they say, is built over time. But trust, like heat, also builds in silence — until it doesn’t.

There will come a moment — not today, and perhaps not for years — when something falters. It may be a budget. A schedule. A system. A public confidence. And when that happens, the question won’t be “Why did no one see this coming?” It will be “Why did everyone assume it wouldn’t?”

The answer, of course, will be the same: Because the regulator said it was safe.

And by then, the heat will be ambient. Quiet. Radiant. Unmistakable.

Following publication inquiries issued by Prime Rogue Inc., several stakeholders were contacted for clarification and commentary regarding the Darlington BWRX-300 licensing process.

The Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO), when asked about its oversight role or engagement with the project, responded via email on April 9, 2025:

“AMO’s advocacy on energy has been in support of a clean, reliable, and affordable energy supply to support local communities and economic growth. Our recent guidance to municipalities has been focused on the defined municipal role in approving projects under the IESO’s Long-Term Energy Procurements. As you are aware, the responsibility for assessing nuclear technology with respect to safety falls to the jurisdiction of the federal and provincial governments, not to municipal governments. AMO does not comment on individual projects or issues related to them such as licensing or siting, instead deferring to municipalities who may choose to comment regarding local circumstances and considerations. As such, we have not provided comment to government, regulatory authorities, or Ontario Power Generation on this matter.”

This posture reflects a broader pattern of municipal disengagement: where jurisdictional deferral becomes operational abdication. The communities adjacent to major infrastructure projects are often the last to be consulted and the first to bear risk—especially when oversight is treated as a federal abstraction.

Inquiries were also submitted to the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), Ontario Power Generation (OPG), and GE Hitachi regarding licensing rationale, environmental assumptions, and public engagement consistency.

All three declined to provide comment.

Their silence is telling. When confidence is granted instead of earned, when oversight is performance rather than protection, when licensing becomes a foregone conclusion rather than a deliberative process—questions are not answered. They are ignored.

And perhaps that is the final lesson of the BWRX-300’s approval. That in Canada’s nuclear licensing system, silence is not absence. It is authorization.

[…] article is not about a privacy request. It is about what happens when the guardians of information weaponize ambiguity, and when the proces… It is about fear of metadata. It is about narrative […]