Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is widely recognized as an institutionally corrupt force. Its leadership of security operations for the 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis, Alberta, therefore warrants close scrutiny and active public resistance. Based on past summits, Canadians should expect abusive policing practices under the guise of international event security.

This is the first installment of a 15-part OSINT series to be published between now and the summit’s opening. Our goal is to provide a comprehensive open-source intelligence overview of the security apparatus surrounding the G7—including Canadian military involvement, participating domestic agencies like the Calgary Police Service, and the full spectrum of foreign delegations to illustrate the pure security theatre of such an international summit.

As these institutions prepare to curtail your Charter rights under a carefully stage-managed security pretext, we will offer insights on how to recognize these abuses and to exercise your own OSINT. This includes notes for journalists, legal monitors, and protestors—though this is not legal advice.

The G7 is security theater. Let’s make it clear that the RCMP remains the most overfunded and under-accountable performer in this spectacle.

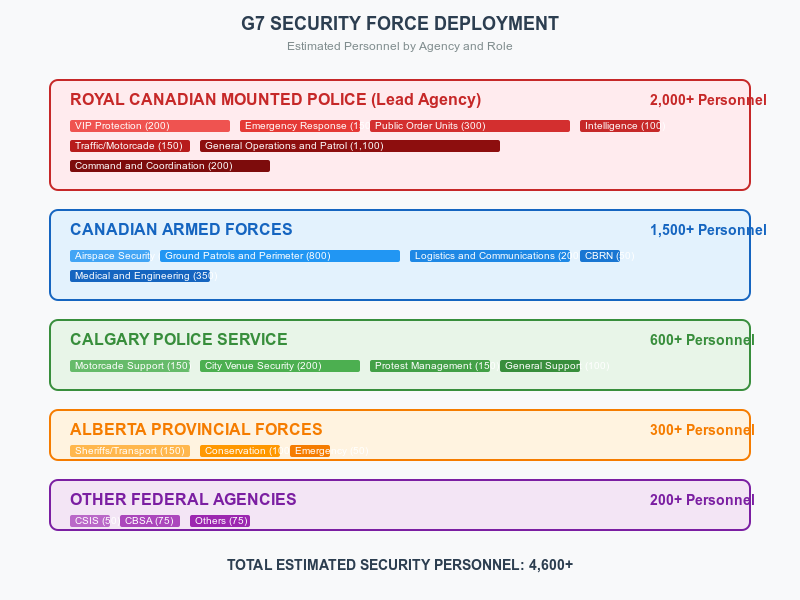

The 2025 G7 Leaders’ Summit in Kananaskis, Alberta will be secured by an Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG) led by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). This multi-agency task force draws on the RCMP’s legal mandate as lead agency for major international events, working in unified command with the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), Calgary Police Service (CPS), Alberta Sheriffs, and provincial Conservation Officers. The RCMP Commissioner retains ultimate authority, delegating a Gold–Silver–Bronze style command hierarchy to coordinate strategic, operational, and tactical elements. Robust plans are in place for protective policing of VIPs, counter-terrorism response, public order management, and integrated military support, all informed by lessons learned from past summits. A Controlled Access Zone (CAZ) will lock down the remote summit site with checkpoints and airspace restrictions, while designated protest zones in Banff and Calgary allow for controlled demonstrations. Civil liberties and community relations are being addressed through public communication, community liaison centers, and assurances that security measures aim to minimize impact on residents. Nonetheless, key challenges include the vast wilderness perimeter, the complexity of multi-agency coordination, and potential protest flashpoints away from the summit site. Overall, open sources indicate an unprecedented but carefully managed security operation, with the RCMP firmly in charge and partners unified to deliver a safe and secure event for all.

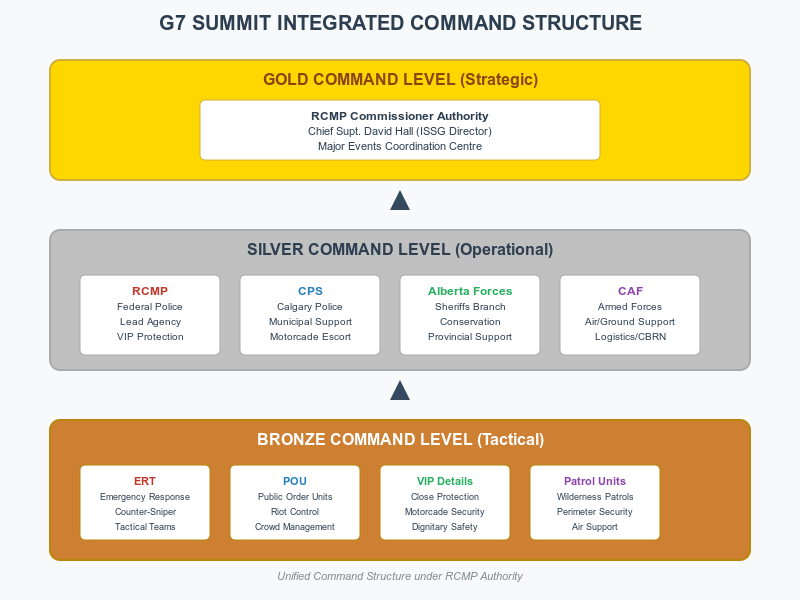

Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG): The RCMP has formed a dedicated ISSG to plan and execute summit security. This unified command brings together multiple agencies and jurisdictions in a single framework:

Unified Command and Roles: The ISSG operates under a unified command structure to ensure all partners work in lockstep. In practice, this mirrors the Gold–Silver–Bronze command doctrine: a strategic “Gold” commander (RCMP-led) sets overall policy, operational “Silver” commanders from key agencies implement plans, and tactical “Bronze” units handle field deployments. RCMP leadership emphasizes that “working in collaboration strengthens our ability to deliver a safe and secure event.” Under this structure, partner agencies assume defined roles – for example:

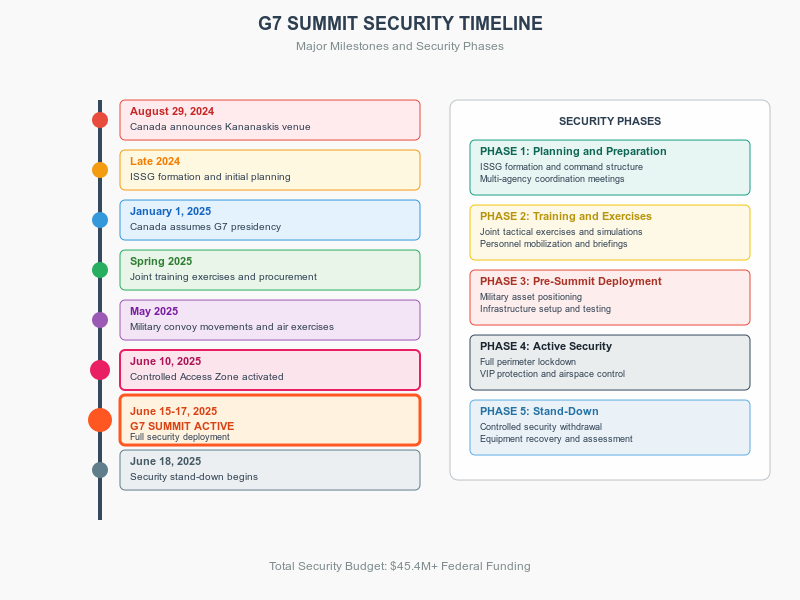

A main command center is established to coordinate all security facets – the RCMP’s Major Events Coordination Centre (MECC) in Calgary is actively engaged in site surveys and multi-agency planning. A forward Tactical Operations Centre (TOC) will be set up near Kananaskis to manage on-site incidents in real time (e.g. at or near the summit venue). The ISSG stood up in late 2024, shortly after Canada announced the Kananaskis venue on August 29, 2024. Throughout 2024–25, the group has followed an interagency planning cycle involving regular coordination meetings, joint training exercises, and site visits. By early 2025 (when Canada assumed the G7 presidency on Jan 1), security planners were already securing key sites and procuring essential equipment in preparation. The RCMP and Public Safety Canada have also run “whole-of-government” exercise programs to test readiness across federal and provincial partners. This methodical build-up ensures the full ISSG is mobilized well before the Summit (June 15–17, 2025), with all command centers and communication networks operational.

The RCMP holds the primary legal authority for safeguarding visiting dignitaries and securing major international summits in Canada. Under Canada’s laws – notably the Security Offences Act and Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act (FMIOA) – the safety of “Internationally Protected Persons” (IPPs) such as G7 leaders is a federal responsibility that falls to the RCMP. By statute, the RCMP has “primary responsibility” to ensure security for the proper functioning of any intergovernmental conference in Canada. This primacy means the RCMP must take a leadership role, though not to the exclusion of other police – local forces still share duties in a supporting capacity. In practical terms, Canadian law mandates that the RCMP oversee protective operations for events like the G7 Summit, with the ability to direct and integrate the efforts of provincial and municipal police.

Within the RCMP’s Federal Policing branch, a specialized Protective Policing program manages VIP security. Key components include the VIP Protection Detail (VIPPD), which safeguards foreign dignitaries and visiting leaders, and the Prime Minister’s Protection Detail, responsible for the Canadian Prime Minister. During the G7, VIPPD officers will work as the principal bodyguards (“inner ring” protection) for visiting heads of state and government. These plainclothes RCMP protective officers are trained in close protection, route security, and emergency evasion tactics. The RCMP’s Protective Operations Response Team (PRT) and Emergency Response Team (ERT) units are on hand to reinforce VIP escorts if high-threat incidents occur. The PRT provides quick response to any protective security incident, while the National Division ERT is a tactical unit trained in counter-assault, hostage rescue, and even aircraft intervention to resolve complex attacks on protected persons.

The RCMP works closely with each visiting leader’s own security detail to ensure a layered protection model. Foreign protective services – for example, the U.S. Secret Service (USSS) for the American president, France’s Gendarmerie protection unit (GIGN/SPHP), the UK’s Metropolitan Police Royalty Protection (SO1), Italy’s Carabinieri VIP unit, Japan’s Security Police, etc. – handle immediate close protection of their principals. These teams form the inner ring around the VIP at all times. The RCMP’s role is to establish the outer ring: a wider security perimeter, motorcade route security, venue screening, and overall incident response around the VIPs. According to official guidance, “within the very inner circle would be the protection of the internationally protected person, for which the RCMP is responsible,” while events around the summit (e.g. protests or crimes in the streets) are handled by local police of jurisdiction. In other words, RCMP and partner agencies divide responsibilities so that RCMP leads on direct dignitary safety, whereas local police address general law and order issues in surrounding areas. This cooperative approach is spelled out in law and practice – RCMP primacy “does not suggest sole responsibility”; rather, the Mounties “share responsibility with the police forces of local jurisdictions,” maintaining partnership and consultation.

In advance of the summit, RCMP protective planners liaise with foreign security delegations to conduct joint site surveys and agree on protection protocols. For example, motorcade movements for each leader are planned in tandem with their detail (e.g. USSS advance teams working with RCMP Traffic and Escort units). There will be secure motorcade staging areas in Calgary for leaders arriving by air, with RCMP-led motorcade teams (including CPS motorcycle outriders) escorting VIPs to Kananaskis under rolling road closures. At the summit venue, each leader’s personal detail handles close security in meeting rooms, while RCMP teams bolster perimeter screening and have ERT sniper-overwatch positioned around the site for the collective safety of all delegates. The Protective Policing Directorate also coordinates counter-surveillance measures – identifying and mitigating any hostile surveillance or plots against VIPs. Notably, RCMP protective officers work hand-in-hand with allied agencies like the U.S. Secret Service, sharing intelligence and deconflicting each other’s operations so there are no gaps or friendly interference. All personal protective movements fall under the master plan of the ISSG, ensuring unity of effort.

The RCMP’s Emergency Response Team (ERT) – a highly trained tactical unit – is a cornerstone of the summit security posture. ERT members will be pre-deployed to provide counter-sniper coverage, quick-reaction force (QRF) capability, and tactical overwatch at all key venues. At Kananaskis, ERT sniper-observers are expected to be positioned on rooftops and high terrain, equipped with long-range optics and rifles to monitor for any long-distance threats. This counter-sniper role is critical given the expansive wilderness and elevated vantage points around the resort. ERT units will also be on standby as a Counter-Terrorism Immediate Response Team – essentially SWAT teams ready to intervene if a hostile incident occurs, such as an armed attack, hostage situation, or barricaded gunman. Their training in close-quarter battle and hostage rescue tactics (including aircraft or motorcade intervention) means they can rapidly confront terrorists or heavily armed adversaries. The RCMP is drawing ERT personnel from multiple divisions: National Division (Ottawa) ERT for VIP protective response, as well as regional ERTs from Alberta (K Division) and possibly Ontario and British Columbia to ensure adequate coverage and relief rotations. This multi-ERT deployment strategy was used in past summits – for example, dozens of ERT members from across Canada were mobilized for the 2010 G8/G20 events.

In addition to ERT, the ISSG will field Public Order Units (POUs) dedicated to managing demonstrations. These units consist of police officers in riot gear trained in crowd control, formations, and arrest tactics. The RCMP and partner police forces will deploy integrated public order teams, likely under a unified command, to any protest sites in Calgary, Banff, or unexpected areas. As part of the “specialized teams” within the unified command, these POUs are ready to contain or disperse unlawful protests, protect critical sites from crowd surges, and handle riot scenarios. They carry less-lethal weapons (batons, shields, tear gas, rubber bullets) but operate under strict rules for use of force. Their presence is intended to deter violent demonstrators and allow peaceful protest to proceed in designated zones. If demonstrations turn aggressive or attempt to breach security perimeters, the public order teams will be the first line of response – supported by ERT if firearms or higher threats emerge. The tactical doctrine since the volatile 2010 G20 summit has been to use a graduated, measured response: maintain a large, highly visible police presence to discourage trouble, but also have rapid tactical backup if situations escalate beyond the control of front-line officers. For summit week, residents and visitors can expect to see groups of police in tactical gear pre-positioned near demonstration sites and at key checkpoints, reflecting a “ready for worst-case” stance as RCMP officials have underscored.

Given the elevated threat profile of G7 events (which could include terrorism or hostage-taking), Canadian special operations forces are almost certainly integrated into the security plan. In past Canadian summits, the elite Joint Task Force 2 (JTF2) counter-terrorism unit has been deployed in a covert support role, ready to intervene in the gravest scenarios. While specific details for 2025 are classified, it is widely known that JTF2 and other Canadian Special Operations Forces (such as the Canadian Special Operations Regiment, CSOR) work in close collaboration with the RCMP during major events. They may form part of the National Counter-Terrorism Plan, positioned to respond to chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) threats, complex assaults, or other scenarios beyond the capability of police. The RCMP’s Critical Incident Program has protocols to hand off command to military special forces if a crisis surpasses police resources. Notably, the CAF’s 2018 summit support included air and sea monitoring and a long-range radar for air threats – implying that, if an airborne or high-end threat materialized, CAF fighter jets or special units would handle it under NORAD auspices. The RCMP and Department of National Defence have likely established liaison teams to ensure JTF2 or other military assets can be seamlessly integrated should an incident arise. All indications from past summits (e.g. Operation Cadence in 2018) show that the CAF defers to the RCMP’s lead, contributing specialized capabilities but not conducting independent law enforcement. This means any deployment of JTF2 or other armed military responders would be at the request of and in coordination with the RCMP Incident Commander, preserving the civilian authority over the operation.

In preparation for the summit, numerous tactical exercises and simulations have been conducted. These likely included tabletop scenarios (e.g. a mock terrorist incident at the venue, or a simulation of a protest blockade) and full-scale rehearsals. Media reports indicate that in May 2025, military aircraft (including CF-18 fighter jets) and helicopters increased training flights over Kananaskis, suggesting drills for airspace security and possibly air intercept exercises. Convoys of military vehicles moving at night from Edmonton to Calgary in the weeks prior also point to logistical exercises and positioning of tactical equipment. The RCMP’s ERT and POUs likely ran joint drills with CAF units (such as the CBRN response teams or communication specialists) to practice interoperability. By summit week, the tactical teams will be fully briefed on rules of engagement and equipped with specialized gear (night vision, armored vehicles, drones for surveillance) to handle any contingency. All these preparations feed into an overall tactical doctrine of layered defense – deter and detect threats early (via intelligence and a strong security perimeter), respond swiftly with overwhelming force if needed, and maintain control of the situation until it is resolved or, if beyond police capacity, until military CT units take over.

The Canadian Armed Forces are playing a crucial support role in the G7 security operation, under the codename likely assigned by CAF (for the 2018 Charlevoix summit, the mission was Operation CADENCE; for 2002 Kananaskis it was Operation GRIZZLY). The 2025 summit is similarly backed by a significant CAF contingent, integrated into the RCMP-led ISSG. The CAF’s involvement is justified by its unique capabilities and resources that augment civilian police. As DND stated after 2018: “the CAF has unique capabilities, so it often supports other government departments… contributing to the safety and security of the G7 was one of the ways the CAF is strong at home.” Key areas of military support include:

Importantly, the CAF’s role is in support of civilian authority. Public statements underscore that military personnel will not engage in law enforcement tasks such as arrests or crowd control. They lack policing powers unless officially deputized. Instead, soldiers supposedly act as an auxiliary: they secure areas and provide capabilities, but any actual enforcement (e.g. arresting a trespasser) is done by police. This principle adheres to Canadian law, where the Armed Forces can aid civil power but remain under RCMP operational direction. The Defence Minister authorized CAF assistance for the G7 under the National Defence Act provisions for Aid to Civil Power, but with strict Rules of Engagement (ROEs) coordinated with the RCMP. These likely specify that armed force by CAF can only be used in extremis (e.g. against a clearly hostile armed threat) and typically only under direct orders from the RCMP Incident Commander. CAF members are embedded in the ISSG structure – for example, military planners have been working in the ISSG Planning Team for months, and on the ground, military liaisons sit in the command centers to ensure seamless communication. Joint training has further solidified this integration: in spring 2025, Canadian Army troops and RCMP units conducted joint exercises in Alberta (reports noted CF members training in convoy operations and mountain patrols in the summit area). All these efforts reprise the successful model from past operations like the 2018 summit, where Operation CADENCE saw over 2,000 CAF personnel deploy in support with no incidents. The RCMP emphasizes that military support is a force multiplier that remains behind the scenes – ideally, the average citizen will notice little of the military beyond perhaps the sight of a distant fighter jet or a camouflaged convoy moving at night.

The RCMP’s authority to lead security for the G7 Summit is grounded in Canadian law and government direction. Under the RCMP Act, RCMP officers are peace officers in every province, allowing them to operate nationwide. Furthermore, the Security Offences Act designates the RCMP as the primary enforcement agency for offences related to the security of Canada, including acts of terrorism or attacks on internationally protected persons, regardless of where they occur in Canada. The Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act (FMIOA), updated in 2001, explicitly gives the RCMP primary responsibility to ensure security for the proper functioning of international summits like the G7. Section 10.1(1) of that Act is often cited: “The Royal Canadian Mounted Police has the primary responsibility to ensure the security for the proper functioning of any intergovernmental conference in which two or more states participate…”. This legal mandate, combined with federal cabinet decisions, is why the RCMP is in charge of this major event even though the summit is in Alberta (where normally provincial or municipal police have jurisdiction).

The security operation falls under the political oversight of the federal Minister of Public Safety (who oversees the RCMP) and ultimately the Prime Minister’s Office/Privy Council Office. In practice, a G7 Summit security memorandum of understanding (MOU) is established between the RCMP and local authorities (e.g. the Province of Alberta and CPS) to formalize roles. Ottawa provides funding to local police for their summit contributions via Public Safety Canada agreements. Ministerial directives have instructed the RCMP to take the lead but also to work collaboratively – a balance codified in FMIOA’s legislative history, which noted that RCMP primacy “simply clarified the lead (but not sole) responsibility” and that consultation and co-operation with local police would continue as before. Thus, the RCMP Commissioner (and his delegate, the Gold Commander) have clear authority to direct the overall security effort, while respecting that Calgary Police and other partners retain their usual policing powers within their areas when not superseded by summit security needs.

Section 6 of the Security Offences Act essentially makes crimes against internationally protected persons (like foreign leaders) a matter of federal concern. It enables the RCMP to assume charge of any investigation or incident response involving such dignitaries. For example, if a serious threat or attack were to occur, the RCMP would lead the response/investigation even if it happened on Calgary city streets. This Act, combined with FMIOA, empowers RCMP officers to act in capacities normally outside their routine jurisdiction, ensuring there is no legal void in security coverage. In Alberta, RCMP already serve as the provincial police in rural areas, but in Calgary (policed by CPS) their summit role is supported by designations such as Special Constable status for out-of-province officers if needed, or simply by virtue of the FMIOA authority that overrides jurisdictional barriers for the event.

To secure the summit, the government has implemented specific legal measures on a temporary basis. A “Controlled Access Zone” (CAZ) has been declared under the authority of either the Aeronautics Act (for airspace) and likely FMIOA or provincial regulations for ground security. This CAZ legally restricts entry to the Kananaskis summit area to accredited persons only, between June 10 and 18, 2025. The RCMP, via federal regulation or an Order in Council, can establish such zones where normal public access is curtailed for security reasons. Warning notices have been issued that anyone attempting to breach the secure zone or trespass beyond checkpoints may be subject to search, detention, or arrest under trespass and security laws. Additionally, the summit has been designated a “major international event requiring special security”, which often triggers specific powers – for instance, in 2010 the government enacted exemptions to certain privacy laws to allow security screening, and similar orders may be in place now. There is also coordination with Transport Canada to enforce no-fly rules and drone bans over the area (violators can face fines or prosecution). On the ground, Alberta’s law enforcement acts (and potentially the Critical Infrastructure Defence Act if relevant) provide police with authority to remove blockades or protesters if they impede critical infrastructure (like highways to Kananaskis).

Public Safety Canada acts as a central coordinating ministry, convening interagency groups to support the RCMP-led plan. An Integrated Security Unit Governance Committee likely exists, linking the RCMP with CSIS (intelligence), CBSA (border services), CSE (communications security, for cyber protection), Health Canada (for health security like pandemic measures or medical readiness), Transport Canada, etc. This mirrors the model from the 2010 summits, where a Privy Council Office Office of the Coordinator for Security (OCS) was created to oversee Olympic and G8/G20 security. For 2025, the Privy Council has again been closely involved; the RCMP’s Major Events Coordination Centre (MECC) works with Public Safety and PCO on everything from budgets to whole-of-government exercises. The RCMP reports that the MECC “has been working closely with Public Safety to advance the G7 Whole of Government Exercise Program and federal working groups” for the summit. This ensures that beyond policing tactics, issues like counter-terrorism intelligence fusion, emergency evacuation plans, and continuity of government are addressed at a national level.

Throughout the planning, Canadian authorities have stressed compliance with legal and constitutional obligations. The RCMP and its partners are expected to adhere to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, even as they implement tightened security. Internal oversight bodies (like the RCMP’s event command and the interagency steering committee) include legal advisors to review security plans for any needed Ministerial Regulations or Exemption Orders. For example, use of facial recognition or advanced surveillance tools would need Privacy Commissioner consultation; any such capabilities, if employed, haven’t been disclosed publicly. Financially, the federal government has provided advanced funding – $45.4 million in supplementary funding to the RCMP was accessed for initial security planning and equipment procurement. Treasury Board and parliamentary committees have been informed of security expenditures, and an after-action audit and evaluation will surely follow, as happened post-2010. In summary, the RCMP’s summit security operation is grounded in a robust legal framework that empowers it to act decisively, but also mandates working in partnership and respecting Canadians’ rights.

The RCMP and ISSG have been proactive in communicating with the public to pretend they are maintaining transparency and community trust. Recognizing the concern that heavy summit security can lead to public anxiety, officials have engaged in outreach and information-sharing well ahead of the event. The ISSG even launched official social media channels (e.g. a Twitter/X account and Facebook page) to disseminate updates. Through local media, RCMP spokespeople like Cpl. Fraser Logan (ISSG media relations lead) have given interviews to explain security activities – for instance, notifying residents about the late-night military convoys and urging caution when driving near them. RCMP media releases have also sought public assistance in security: “We always look to those in the community to tell us what is out of place or not normal for your neighbourhood,” Logan noted, encouraging locals to report suspicious activity. This messaging enlists the community as eyes and ears, leveraging OSINT from citizens to detect potential threats (e.g. unfamiliar persons scouting areas, abandoned vehicles, drone sightings).

A dedicated G7 Community Information Centre was opened at the Stoney Nakoda Resort & Casino (on Stoney Nakoda First Nation land, near the entrance to Kananaskis) to provide a face-to-face point of contact for locals. Staffed by ISSG officials, this centre has operated Monday–Friday afternoons to answer questions from residents, businesses, and Indigenous community members about road closures, accreditation, and security measures. It was scheduled to remain open until June 9, just before the summit, to ensure locals could voice concerns or obtain permits (such as passes for residents who live inside the controlled zone). The RCMP has also liaised with the Nakoda First Nation leadership and the Town of Canmore to address any cultural or environmental concerns – for example, ensuring that sacred sites or wildlife are respected even as security is tightened. In Banff and Canmore, town hall meetings were reportedly held where ISSG representatives briefed local officials and hoteliers on what to expect during the summit (e.g. temporary traffic interruptions, ID checks for those entering certain areas). The goal of these efforts is to reassure the community that their safety and daily life are priorities, and to mitigate rumors by providing accurate information.

RCMP leaders have repeatedly and spuriously stated they aim to make the summit as least disruptive as possible for residents and visitors. “We’re aiming for the least amount of impact on people,” spokesperson Logan emphasized regarding the security footprint. While this is disingenuous, Practically it means designing road closures and detours to keep tourist traffic flowing in Banff and Canmore, keeping businesses open where feasible, and limiting the visible militarization of public spaces. Banff’s town council was initially concerned about a designated protest zone being placed downtown, but ISSG worked with them (read coerced them) to manage location and ensure local safety. The Banff official website euphemistically reassures that impact on the town is expected to be minimal and “business as usual” during the summit, aside from a short list of affected amenities and temporary closures. By highlighting that Banff routinely handles thousands of tourists daily, officials are framing the summit as just another surge of visitors – albeit one with unique security needs. This is PR – not reality.

Peaceful protest is a protected right in Canada, and summit security planners have made accommodations for demonstrations while still keeping the actual summit site secure. The ISSG, in consultation with local authorities, has established designated Demonstration Zones (DDZs) in the region. One official zone will be in the Town of Banff, and three additional zones in the City of Calgary. By providing these outlets – for example, a zone in Banff at a public park or parking lot, and zones in Calgary such as Olympic Plaza or near City Hall – authorities claim allow protesters to assemble and express their messages within sight of media cameras and with live video feeds broadcast to the summit venue and international media centre. This novel idea (broadcasting the protest messages to delegates) is meant to ensure world leaders are at least aware of demonstrators’ views, despite being physically removed. This is of course a disingenuous PR spin used to mask the abrogation of protesters’ Charter rights. The flip side is that protestors will not be allowed anywhere near Kananaskis itself; it’s simply too remote and securitized (the summit hotel is surrounded by miles of restricted wilderness so the government is copping out by violating civil liberties). Civil liberties groups have legitimately raised concerns about this setup – noting that corralling protesters far from the event diminishes their impact. Banff officials initially balked at hosting a protest site, worried about disruption to their downtown. However, they’ve acknowledged the need to balance rights with security. The RCMP has likely put conditions on demonstrations (size, no structures or weapons, etc.) and will station Liaison Officers and police monitors at each DDZ to facilitate lawful protest. Any march outside those zones would be quickly intercepted by police. As Global News reported, during the 2018 G7 a heavy police presence and an isolated summit site “doused all but a smattering of demonstrations,” as most protestors were kept 140 km away in Quebec City. Only small groups attempted to block highways and were swiftly handled by riot police. The same approach is evident for 2025: the combination of a remote venue and designated protest zones is ostensibly intended to prevent major clashes. RCMP statements reinforce that they are prepared for demonstrations – “ready to deal with a large number of demonstrators” and to “respond quickly to any public order disturbances” – but hope to see protests remain peaceful and confined to the agreed areas. In reality, and in line with its reputation for breaching civil rights with more efficiency than any of its investigations, RCMP and tasked agencies are likely prepared to brutally assault protesters should they find any excuse to do so.

Summit security invariably entails enhanced surveillance, which raises civil liberties questions. The ISSG has not publicly detailed all tools used, but OSINT indicators suggest measures like advanced CCTV cameras, license plate readers, and drone detection systems are being deployed. The RCMP has a National Technology Onboarding Program that likely brought in temporary systems such as high-resolution surveillance cameras around Kananaskis Village and possibly facial recognition software for accredited persons (for instance, to verify identities at checkpoints). Any use of facial recognition or other intrusive tech would be governed by Canadian privacy laws – police would assert they are only surveilling public areas for security threats, not for general population monitoring. RCMP officials have emphasized that their approach is “intelligence-led and based on ongoing threat and risk assessments”, tailoring measures to credible threats. They deliberately avoid disclosing specifics, partly to preserve tactical advantage and partly to avoid alarming the public. This lack of detail sometimes fuels speculation among activists that the police might overreach in surveillance – notably because they have a history of doing so. However, independent oversight bodies (like the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency, NSIRA) could review RCMP techniques after the fact if any complaints arise. As one can imagine, this is a toothless bureaucratic process reflecting the Canadian bureaucracy’s broader indifference to Charter rights. During the summit, expect communication intercepts to be used against potential violent agitators – CSIS and CSE, within legal limits, will be monitoring for any extremist plots. But for average citizens, the RCMP has stated that law-abiding visitors “will be able to move freely” in non-restricted areas, and that visible security (while substantial) will remain respectful and helpful. Based on past events, this is unlikely to be true.

The summit takes place on the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples (Treaty 7 region). The RCMP and federal government have “engaged” local First Nations – notably the Stoney Nakoda Nation and Tsuu T’ina Nation – in dialogue about the summit. Indigenous observers will be present to ensure sacred sites or ceremonies are not disrupted. Some Indigenous groups have used G7 events in the past to highlight their issues; the ISSG is undoubtedly aware that any heavy-handed response to Indigenous demonstrators would be politically sensitive. As such, community liaison officers are likely assigned to Indigenous leaders to keep open lines of communication, and to more efficiently silence their voices This is part of a broader propaganda structures aimed at providing the illusion of transparency and accountability. For example, the RCMP invited media to tour some security installations (to demystify (mislead) them) and has provided contacts for local residents to get credible information (like the email and hotline to report suspicious activity or ask security questions). In essence, the RCMP’s commitment to optics far supersedes its commitment to the Charter.

Canadian civil liberties organizations and Amnesty International have deployed observers to monitor police conduct during the summit. Their goal is to document any infringement of rights such as unlawful searches, kettling of protesters, or use of excessive force. After the 2018 summit, Amnesty reported that while there were no serious injuries, the “impressive display of police force” created “a truly fearful atmosphere” for people wishing to protest. Observers noted officers in 2018 carrying assault rifles and using riot-control weapons in ways that intimidated peaceful protesters. They also cited some instances of police allegedly using abusive language or refusing to cooperate with human rights observers. For 2025, the RCMP is undoubtedly aware of these past critiques, and is likely seeking to bypass them without addressing the underlying issues. Commanders have likely instructed officers to use a measured approach and to facilitate peaceful protest to the extent possible. Nonetheless, the sheer scale of security – hundreds of tactical police in public – can inherently be seen as intimidating. The RCMP has tried to counter this perception by highlighting community policing aspects: patrol officers will be “available to assist residents, answer questions, and address any concerns” in the area, showing a friendly face while also deterring trouble. They’ve promised “visibility and accessibility so the community feels supported and reassured throughout the summit”. Achieving this balance is challenging: they must project strength to dissuade threats, yet also avoid alienating the public. The true test will come during the event – if protests remain peaceful and residents experience minimal intrusion, it will falsely validate the RCMP’s community-focused propaganda strategy. Any missteps (e.g. mass arrests of non-violent protesters or undue force) would certainly be seized upon by watchdogs and could tarnish the operation’s legacy, as happened after the 2010 G20 in Toronto. The RCMP is unlikely to care.

The RCMP’s approach to Kananaskis 2025 is heavily informed by lessons from previous major events in Canada. This is not the first time such an elite gathering has been held in Kananaskis; in June 2002, the G8 Summit (then G8, including Russia) took place at essentially the same location. Code-named Operation GRIZZLY, the 2002 security operation was, at the time, one of the largest in Canadian history, involving several thousand soldiers and police. That summit occurred just 10 months after 9/11, so security was extraordinarily tight and counter-terror measures were at the forefront. Canadian CF-18 fighters enforced a no-fly zone and were seen/heard daily over the area. The military even deployed Air Defence Anti-Tank System (ADATS) missiles at locations around Kananaskis – capable of shooting down aircraft up to 10 km away. U.S. President George W. Bush attended in 2002 and reportedly chose to fly in daily from a base in Montana rather than stay overnight, underscoring the perceived security risk (though this was never officially confirmed). On the ground, police and military presence was ubiquitous: locals recall armed soldiers greeting hikers on trails and scores of police on mountain bikes patrolling Canmore’s streets. Protests in 2002 were minimal, largely due to the remote locale – only a few hundred demonstrators went to Calgary or Ottawa to rally symbolically, with none reaching the actual summit site. The success of 2002 in avoiding violence set a precedent: remote, defensible locations became the preference for Canadian hosts (a stark contrast to summits in dense urban areas like Genoa 2001 which saw riots). Put another way, the government continues to prioritize making its violence against citizens unseen.

Fast forward to 2010, Canada hosted back-to-back the G8 Summit in Huntsville, Ontario and the G20 Summit in downtown Toronto. The integrated security operations then were massive. Over $846 million was spent on security, with the RCMP receiving nearly half that funding and deploying thousands of officers. Lessons from 2002 and the 2010 Olympics (held in February 2010) were applied – an ISSG model was used, and indeed many RCMP planners from the Vancouver Olympics transferred to the G8/G20 project. The 2010 Toronto G20, however, became infamous for its civil liberties controversies: While the summits were safely held, protests in Toronto turned violent with storefront vandalism, and police undertook mass arrests of over 1,100 people, many of whom were detained without charge – in the true spirit of the RCMP’s operations. Reuters noted that the Toronto G20 protests “turned violent amid riots and a police crackdown,” contrasting with how the 2018 G7 later saw far fewer clashes. Reviews and after-action reports criticized parts of the 2010 operation – communication breakdowns, unclear orders, and heavy-handed crowd control (like the controversial “kettling” of protesters in the rain). The RCMP’s own evaluation of the 2010 G8/G20 identified that “roles and accountabilities for providing oversight and leadership… were not always clear,” particularly between a newly created PCO security office and the RCMP command. It also found that best practices needed to be better recorded and shared. Lessons learned are more likely to be glossed over than implemented.

In response, the RCMP improved its major event doctrine: establishing clearer command unity (so that by 2018, the Privy Council’s oversight role was streamlined with RCMP’s operational role), enhancing training, and updating public order tactics. One finding from the RCMP’s 2010 evaluation was that “best practices and lessons learned from the Summits have been retained for future major events.” Indeed, many 2010 summit veterans were involved in planning the 2018 G7 in Charlevoix, Quebec, and now the 2025 G7. By 2018 G7 Charlevoix, the approach was refined: a remote location (La Malbaie) was chosen similar to Kananaskis, and security forces numbered around 10,000 police and military. The RCMP-led ISSG in 2018 successfully kept protesters at bay – as mentioned, only 10 arrests occurred and protests were “largely peaceful” albeit in Quebec City far from the summit. A heavy police deployment (riot police in the streets, legislative buildings pre-emptively closed, etc.) prevented disruption. This was praised by security officials as readiness paying off – “we were ready for all eventualities,” said RCMP spokesperson Capt. Philippe Gravel – but civil liberties groups like Amnesty criticized the “climate of fear and intimidation” it created. The lesson heading into 2025 seems to be finding the sweet spot: deter threats and disorder, but try not to over-police or provoke unnecessary fear.

Other major events have contributed lessons too: the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics (which involved an enormous ISSG of 16,000 security personnel from RCMP, local police, military and private security) taught integration of many units and the importance of good communications. The Olympics were seen as a security success with no serious incidents, thanks in part to intelligence-led pre-emptive measures and community engagement. Techniques from 2010, like integrated command centers and interdisciplinary threat assessment teams, are now standard for G7. Additionally, the 2018 G7 and 2010 G20 after-action reports likely informed the current operation’s emphasis on early engagement with protesters and clear assignment of command roles to avoid confusion. For instance, in 2025 the RCMP is both the strategic lead and hands-on operational lead, and there is no separate “OCS” layer that might duplicate functions. The coordination with Public Safety is structured to support, not bypass, RCMP command. This clarity should help avoid the leadership confusion noted in 2010.

Technology and innovation have also advanced. Past summits saw experiments with new tools (the 2010 Olympics introduced extensive CCTV networks and accreditation scans; 2010 G20 controversially used sound cannons/LRAD). By 2018 G7, authorities used modern drones for surveillance but also had to counter potential drone threats by enforcing no-drone zones. For 2025, one can infer they are using state-of-the-art surveillance and counter-drone systems – a far cry from 2002 where such technology was limited. Every summit adds to the knowledge base: e.g., learning from 2018 how to manage social media misinformation or how to better liaise with journalists (2018 had a huge International Media Center in Quebec City, and now 2025 will have one at Banff Centre, which is being secured with lessons from 2018 regarding media access and security checks).

In summary, the RCMP has iteratively improved its summit security playbook. Kananaskis 2025 is almost a full-circle moment, coming 23 years after the first Kananaskis summit. The world has changed (the threat of terrorism remains, new threats like cyber attacks exist, and public expectations for rights are higher), but the remote “fortress” summit model remains effective. The RCMP is leveraging the institutional memory of past operations: information-sharing between event commanders, formal lessons-learned reports, and major event training exercises (in fact, many security personnel rotate through G7, G20, Olympics, etc., building a veteran cadre). As a result, the 2025 summit security is a product of all that came before – aiming to repeat successes (preventing violence or terror) while avoiding past pitfalls (unnecessary infringements on civil liberties or inter-agency friction).

Open-source information reveals a lot about the summit security operation even without official briefings. Over the past months, a series of OSINT indicators have signaled the growing security presence:

Overall, the lead-up to the summit has produced a trail of open-source breadcrumbs that paint a picture of an immense security machine gearing up. The RCMP and its ISSG partners have balanced public information with operational secrecy – sharing just enough to keep locals informed and bad actors guessing. By collating OSINT from news reports, official websites, and on-the-ground observations, one can anticipate the broad contours of summit security: a fortified rural venue, a highly coordinated multi-agency force of thousands, and a strategy to keep trouble far from the world leaders.

Despite the extensive preparations, the summit security team faces several key challenges and potential vulnerabilities that they must continuously manage:

In conclusion, the RCMP-led security operation for the 2025 G7 Summit is comprehensive and robust, yet it must continually adapt to a range of challenges. By leveraging Canada’s full spectrum of capabilities – from local policing to military force – and learning from past events, the ISSG aims to leave nothing to chance. However, as any intelligence analyst knows, there are no zero-risk scenarios. The true measure of success will be a summit where the leaders are safe, the public remains secure and free from undue hardship, and global attention stays on the summit’s diplomatic outcomes rather than security failures. So far, open-source intelligence suggests the RCMP and partners are engaging in one of the largest spectacles of security theater in Canadian history, striving to make the 2025 G7 at Kananaskis as expensive – and disruptive to the community – as possible.

Editor’s Note: All of this information is sourced from the public domain and logical inference.

[…] The upcoming G7 Summit (June 15–17, 2025) in Kananaskis, Alberta will transform a peaceful mountai… World leaders will convene at the Pomeroy Kananaskis Mountain Lodge, and far from the public eye a RCMP-led Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG) will orchestrate an extensive security blanket over the region. In support, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) is deploying a substantial joint task force – a mission of military aid to civilian law enforcement reminiscent of the 2002 G8 Summit (code-named Op GRIZZLY) held in the same locale, albeit updated for modern threats and sensitivities. […]

[…] Information Sources: Follow but be incredibly skeptical of RCMP and G7 official channels. The RCMP’s Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG) site publishes traffic management, closures and “demonstration guidelines” for the Summit. For […]

[…] security and map out every detail of the President’s movements. They liaise closely with the RCMP’s Protective Operations unit (which protects visiting VIPs in Canada) to integrate plans. Early in the process, USSS invites local and federal partners to planning meetings. Past examples […]

[…] The 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis promises fortress-level physical security – motorcades, armed pat…– yet a quiet invasion vector may slip through in attendees’ pockets. Enter dating apps: Tinder, Bumble, Grindr, Hinge. These platforms, driven by GPS and human loneliness, can double as ambient surveillance networks inside high-security events. With a darkly satirical twist of fate, horny swipes and profile bios could expose patterns that no amount of fencing or counter-sniper teams can hide. This report explores how dating apps might be weaponized as OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence) tools during the G7 summit, mapping human behavior and security gaps in real time. From warzones to global summits, the evidence is mounting that when officials, security personnel, or journalists mingle online in search of hookups, they may inadvertently broadcast sensitive metadata – location, movements, affiliations – to any adversary savvy enough to listen. The goal here is both critical and a bit tongue-in-cheek: to assess just how vulnerable our VIPs and “protectors” are when “love is in the air” (or at least in the apps) during a lockdown event, and whether a clever spy could “swipe right” on state secrets while everyone else is focused on guarding the perimeter. […]

[…] The 2025 G7 Leaders’ Summit in Kananaskis, Alberta (June 15–17, 2025) will be protected by a maj…ian Armed Forces – has already mapped out a “controlled access zone” around Kananaskis village (June 10–18) and designated three protest zones in Calgary to contain demonstrators. Observers expect heavy police presence, road closures and checks (e.g. parkland trailheads and highways will be locked down) akin to previous summits. Key threats include large-scale protests (indigenous land rights, pipeline and climate activists, anti-globalization groups), targeted extremist violence (including far‐right militants), lone‐actor attacks on high‐profile leaders (Trump will attend) and general criminal disturbance. Canada’s national terrorism threat level remains Medium (meaning an attack “could occur”), so a serious insider attack or explosive incident, while unlikely, cannot be entirely ruled out. […]

[…] The upcoming G7 Leaders’ Summit (June 15–17, 2025) in Kananaskis, Alberta will see an unpreceden…As one of the visiting delegations, Japan will field its own protective teams to safeguard Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba and accompanying officials, working in close coordination with Canadian authorities. This report provides an open-source intelligence (OSINT) assessment of Japanese protective services, counterterrorism units, and diplomatic security structures likely involved in supporting the Japanese delegation. It examines the role of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police “Security Police” (SP) detail, potential deployment of the Special Assault Team (SAT), intelligence liaisons from the Cabinet Secretariat, transport and logistics (VIP aircraft and armored vehicles), legal permissions for armed foreign agents in Canada, comparisons to past summits, and observable OSINT signatures of these activities. The emphasis is on how Japan’s security posture integrates with host-nation services (the RCMP and partners) and allied counterparts to ensure a safe and seamless G7 Summit. […]

[…] to coordinate with Canadian intelligence on summit threats (a practice dating back decades). For the G7, MI5 would liaise with CSIS (Canadian Security Intelligence Service) and the RCMP’s Int…MI6 (the Secret Intelligence Service, or SIS) and GCHQ also plug into this effort via the Five Eyes […]

[…] All foreign protective details must closely coordinate with the RCMP-led ISSG to avoid friendly-fire… French security leaders participate in advance liaison with Canadian authorities – for example, French “précurseur” teams (advance security scouts) typically arrive weeks in advance to work with local police on venue security and motorcade routes. At the summit itself, the French team operates under RCMP overall authority for venue security, but retains responsibility for immediate protection of the French President. Deconfliction protocols ensure that French snipers or armed agents are known to the ISSG command center. Communication links are established so that, in an emergency, GIGN and RCMP tactical units can coordinate their response. This integration is standard practice – for instance, during the Biarritz G7 (2019) in France, SDLP officers liaised with visiting countries’ security teams, and by the same token in Canada the visiting French team liaises through designated RCMP security liaisons. […]

[…] Alberta Health Services (AHS) has been deeply involved in preparing for the 2025 G7 Summit. In fact, AHS began planning its medical response in 2024, coordinating with the G7 Integrated Securit…An AHS sourced noted, the health system is being readied for “a variety of scenarios, including […]

[…] […]

[…] These are specialized first-response units of the Polizia di Stato designed to react to terror attacks or high-risk incidents domestically. UOPI teams are stationed in Crime Prevention departments and major airports (e.g. Malpensa, Fiumicino) and are equipped for quick intervention with rifles, body armor, and ballistic shields. While primarily a domestic asset to contain threats until NOCS arrives, UOPI operators may augment overseas security details in a support role. For foreign deployments (like G7 summits), Italy might dispatch a small UOPI element to reinforce perimeter security or protect key locations (e.g. the Italian delegation’s hotel or aircraft) under the coordination of NOCS and host nation police. Their formation is typically in 4-5 person teams with robust firepower (Beretta ARX-160 rifles, MP5 SMGs, etc.) and high visibility gear to deter attacks. The RCMP – as Canada’s lead agency for VIP protection and summit security – liaises directly w… […]

[…] drew global scrutiny. This report examines major summit incidents, revealing recurring failures: over-militarized policing, false threat narratives, draconian restrictions on assembly, intrusive surveillance, and scant […]

[…] military confrontation has sharply elevated global terror alert levels just 48 hours before the G7. Canada’s security establishment is reacting with an unprecedented lockdown of the Kananaskis summi… A 13-mile secure perimeter around the remote mountain venue is effectively turning Kananaskis into […]

[…] the meeting a time to “protect our citizens, defend our values and deliver real solutions.” In reality, Kananaskis was transformed into a fortified theater where public scrutiny was all but b… remote mountain venue – marketed with images of serene lodgepole pines and Rockies majesty – […]