Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

The upcoming G7 Leaders’ Summit (June 15–17, 2025) in Kananaskis, Alberta will see an unprecedented security operation led by Canada’s Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG). As one of the visiting delegations, Japan will field its own protective teams to safeguard Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba and accompanying officials, working in close coordination with Canadian authorities. This report provides an open-source intelligence (OSINT) assessment of Japanese protective services, counterterrorism units, and diplomatic security structures likely involved in supporting the Japanese delegation. It examines the role of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police “Security Police” (SP) detail, potential deployment of the Special Assault Team (SAT), intelligence liaisons from the Cabinet Secretariat, transport and logistics (VIP aircraft and armored vehicles), legal permissions for armed foreign agents in Canada, comparisons to past summits, and observable OSINT signatures of these activities. The emphasis is on how Japan’s security posture integrates with host-nation services (the RCMP and partners) and allied counterparts to ensure a safe and seamless G7 Summit.

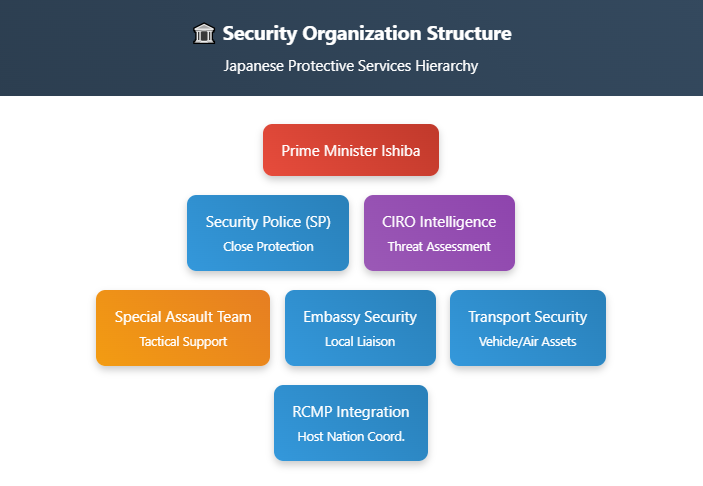

Japan’s primary VIP protective unit is the Security Police (SP) of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department’s Security Bureau. SP agents are elite close-protection officers assigned to safeguard the Prime Minister and other dignitaries both domestically and abroad. Whenever the Prime Minister travels overseas – such as to the Kananaskis G7 – a contingent of SP officers accompanies him to provide 24/7 personal protection. This includes advance teams who arrive early to liaise with the host country and scout venues, as well as close protection teams that stay near the VIP at all times. The SP detail for an extended summit typically operates in shifts, ensuring the Prime Minister is under continuous protection while allowing officers to rotate and remain alert. Open sources do not disclose the exact team size, but it is estimated that dozens of SP personnel deploy for an event like the G7, divided into units covering close escort, motorcade security, residence/hotel security, and advance recon. This structure ensures that the Japanese leader is guarded round-the-clock without overtaxing individual officers during the multi-day summit.

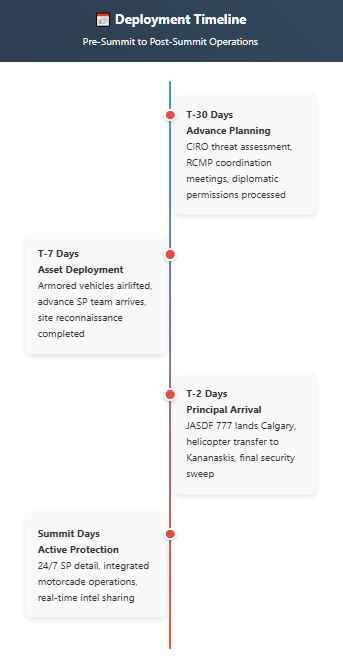

In foreign deployments, SP units integrate their operations under the oversight of the host nation’s security framework. For Kananaskis 2025, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) – through the ISSG command – is the lead for overall summit security. Japanese SP commanders work closely with the RCMP to harmonize protection plans, motorcade movements, and incident response. Well before the summit, Japanese security officials (often via the Embassy in Ottawa) meet with Canadian counterparts to agree on protocols. Liaison officers from the SP or the Embassy’s security staff are embedded with the ISSG coordination center to facilitate real-time information sharing and deconfliction. Indeed, standard practice is that SP officers liaise with local police for all aspects of the visit, from site security at official venues to scouting any off-site events. This ensures the Japanese team’s plans are known to the RCMP and aligned with broader G7 security measures.

While in Canada, the SP agents maintain a layered protective posture similar to their operations in Tokyo. A core detail of plainclothes officers forms a tight circle around the Prime Minister during any movement or public appearance, trained in close-quarters protection and rapid evacuation techniques. They are equipped with concealed firearms (typically small handguns like SIG Sauer or Glock pistols) and communications gear, just as they would be in Japan. Additional SP officers handle residence security – for example, controlling access to the PM’s hotel floor and room, and performing counter-surveillance in the vicinity. SP drivers or Cabinet Office drivers (since the PM’s official car is driven by a trained civilian driver) operate the armored vehicles in the motorcade, with SP agents riding in the lead and follow cars. During motorcades, SP vehicles coordinate with RCMP escort units and local police for route security and traffic control. At the summit venue (the Pomeroy Kananaskis Lodge), SP agents will station at the conference room entrances when the PM is present and accompany him between meetings. In all these activities, the SP detail remains in constant communication with Canadian security command, using designated radio channels and joint protective intelligence updates to respond to any threat.

Notably, Japan upgraded its VIP protection practices after the tragic assassination of former PM Shinzo Abe in 2022 and an attempted attack on PM Kishida in 2023. The National Police Agency increased the number of SP officers and heightened training and planning standards for dignitary protection. These reforms will be evident in Kananaskis: the Japanese SP team will adhere to strict new security guidelines and demonstrate a proactive approach in coordination with Canadian hosts. All possible measures – from bag checks and screening to emergency evacuation drills – have been considered to avoid any security lapse. The SP detail’s goal is seamless cooperation with RCMP and other G7 security units, so that Japan’s Prime Minister is fully protected without impeding the host country’s overall security plan.

Japan’s Special Assault Team (SAT) is an elite police tactical unit analogous to SWAT or counterterrorism teams in other countries. The SAT is normally tasked with high-risk operations (hostage rescue, armed standoffs, counterterror raids) within Japan. However, the question arises under what conditions a SAT component might be deployed internationally to bolster security for the Prime Minister. Generally, Japan is cautious about sending armed tactical units abroad due to legal and sovereignty considerations. In most G7 summits hosted in friendly countries like Canada, Japan does not overtly deploy the SAT, relying on the host nation’s specialized teams (e.g. the RCMP Emergency Response Team in Canada) for tactical response. The Japanese SP detail is considered sufficient for close protection in a low-risk environment, while Canadian authorities provide outer-perimeter tactical coverage (snipers, SWAT teams, quick reaction forces) for all delegations.

That said, there is precedent for discreet SAT involvement in overseas visits under high-threat circumstances. Japanese media have reported that the SAT could be dispatched alongside the NPA’s Terrorism Response Team – Tactical Wing for Overseas (TRT-2) when Japanese nationals or VIPs face extraordinary danger abroad. The TRT-2 was established after incidents like the 2013 In Amenas Algeria attack to enable Japanese police to respond overseas, and it has been used for crisis liaison (for example, deploying to Tunisia after a terrorist attack on tourists). In a summit context, if intelligence suggested a direct terrorist threat to the Japanese Prime Minister that exceeds local countermeasures, the Japanese government might attach a small SAT element to the delegation. Such an element would likely operate in civilian attire and in an observational role, shadowing the SP detail rather than acting independently. Their presence would be chiefly for rapid response to an attack on the Japanese principal until host nation forces intervene. This scenario is more likely in unstable regions or war zones – for instance, if the PM visits an active conflict zone, an armed SAT team might covertly accompany him.

For the Kananaskis G7, Canada is a stable, secure environment with very robust security forces, so a SAT deployment is unlikely to be publicized. However, Japan is taking no chances in the current global threat climate. It’s possible that a handful of SAT operators have been assigned to the wider support team as a contingency, especially given recent global terrorism trends. During the 2016 G7 in Ise-Shima (hosted by Japan), SAT units were actively on duty at the summit venue. And notably, during the 2023 Hiroshima G7, when Ukraine’s President Zelenskyy attended as a guest under high risk, Japanese SAT operators were part of his close protection detail as an extra layer of security. This shows the NPA’s willingness to utilize SAT for high-threat dignitary protection when needed. If any SAT personnel are in Alberta, they would be coordinating with the RCMP’s tactical teams and possibly with allied units like the U.S. Secret Service’s Counter Assault Team (CAT) or Canada’s Joint Tactical Teams, ensuring familiarity with each other’s procedures. Joint exercises and exchanges have given SAT exposure to allied special units (they have trained with Germany’s GSG-9 and Australia’s Specialist Response Group). In summary, an overt SAT presence at the G7 is unlikely unless a crisis emerges, but Japan has the capability on standby. The integration with host nation tactical command would be tight, as any use of force by foreign personnel on Canadian soil would require clear authorization and real-time coordination to avoid confusion with Canadian responders.

Accompanying the Japanese delegation will be officials responsible for intelligence support and crisis management, chiefly from the Cabinet Intelligence and Research Office (CIRO). CIRO (内閣情報調査室, “Naichō”) is Japan’s top intelligence agency under the Cabinet Secretariat, directly reporting to the Prime Minister. In an event like the G7, CIRO plays a critical role in threat assessment and information sharing. It is standard practice for senior CIRO officers or analysts to be embedded with the Prime Minister’s traveling party to provide real-time intelligence updates and liaise with foreign security services. These intelligence liaisons act as the bridge between Japan’s intelligence community and host or allied agencies.

In the run-up to the summit, CIRO would have worked with Canada’s intelligence service (the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, CSIS) and possibly the multi-agency Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre (ITAC) to evaluate threats specific to the summit. Japan is also part of international intelligence partnerships (including the “Five Eyes” via the U.S. and allied channels), so CIRO likely engages in joint threat assessment exercises with counterparts from the G7 nations. By the time the delegation arrives in Kananaskis, a combined situational awareness picture will have been formed, covering potential terrorist plots, espionage risks, cyber threats, and disruptive protest groups. A CIRO liaison officer can sit in the Canadian security operations center to exchange any actionable intelligence in real time, ensuring that if a threat to Japanese interests emerges (for example, a specific threat against the Japanese PM by an extremist group), Canadian authorities are alerted immediately, and vice versa.

Furthermore, Japan’s Cabinet Secretariat Crisis Management team often travels with the PM for major summits. This could include staff from the Cabinet Information Collection Center or the Cabinet Intelligence Committee, who monitor security developments and advise on emergency responses. They coordinate closely with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) representatives and the Japanese Embassy in Ottawa. The Embassy’s security attaché (usually a senior NPA officer assigned abroad) is a key figure who has local connections with Canadian law enforcement and can facilitate quick communication. During the summit, if any incident (even a minor protest targeting the Japanese delegation or an intelligence alert) occurs, the CIRO and crisis management team will convene with the PM’s advisors and Canadian officials to decide on responses – for instance, altering the PM’s schedule, enhancing protective detail, or disseminating advisories to Japanese nationals in the area.

It’s also worth noting that Japan’s intelligence presence may include members of the Public Security Intelligence Agency (PSIA) or the Defense Intelligence community if needed (for example, if there were a military-related threat, a liaison from Japan’s Defense Intelligence Headquarters might join). All these inter-agency efforts feed into providing the Prime Minister with up-to-date information so he can focus on diplomacy knowing the security picture is under constant review. In sum, Japan’s delegation carries an intelligence “cell” that works hand-in-hand with Canadian and allied intelligence during the G7 – a vital component of modern summit security.

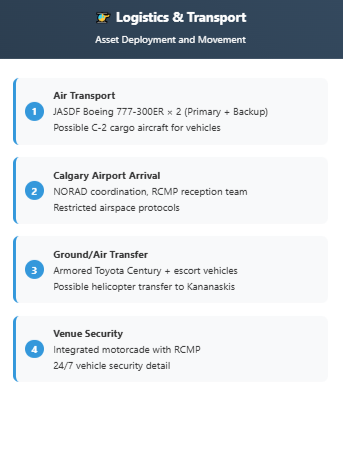

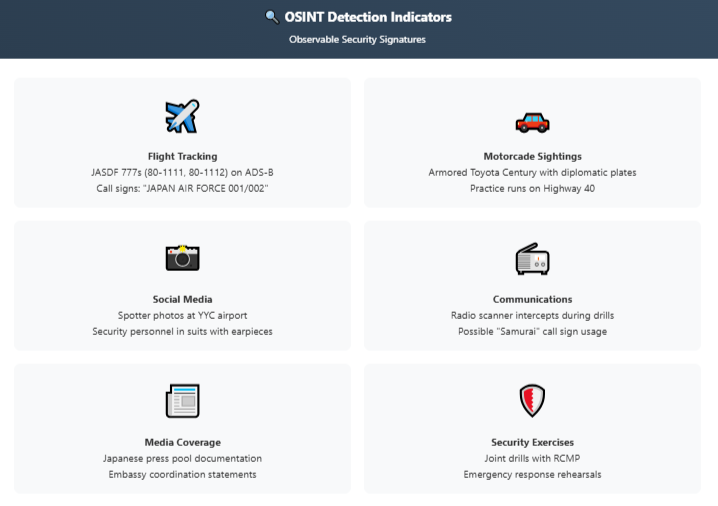

A high-profile overseas visit requires Japan to manage complex transport logistics for both air travel and on-ground mobility. The Japanese Prime Minister will arrive in Canada aboard the Japan Air Self-Defense Force Boeing 777-300ER VIP aircraft. Japan operates two nearly identical Boeing 777-300ERs as its government transport planes (known by the callsigns Japanese Air Force One and Two when the PM or Emperor is aboard). These aircraft are part of the JASDF 701st Squadron and have state-of-the-art communications and security systems. As is customary, both 777s deploy together on any major mission, one serving as the primary aircraft for the Prime Minister and the other as a backup/support plane. Spotters have noted that they fly under call signs like “Japanese Air Force 001 Heavy” and “002 Heavy” on international sorties. For example, during the G7 in Germany (2022), two JASDF 777s were seen landing in Munich with the Japanese delegation. We can expect a similar arrival at Calgary International Airport prior to the summit – likely a couple of days in advance to allow for acclimation and rehearsals. Canadian air traffic control (NAV CANADA) and NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command) will coordinate tightly on this arrival. Typically, a restricted airspace (Temporary Flight Restriction) is in effect around summit time; NORAD may deploy fighter jets or AWACS to monitor the Japanese aircraft as it enters Canadian airspace, ensuring it has a secure corridor.

Upon landing in Calgary, the Japanese delegation will be met by an RCMP and Canadian Forces reception team. It’s common for G7 leaders to then transfer closer to the summit site via helicopter (to minimize time on public roads). In 2002’s G8 at Kananaskis, many leaders were flown in by Canadian military helicopters from Calgary airport to Kananaskis. In 2025, a similar plan is likely: the Prime Minister could board a Canadian CH-148 Cyclone or CH-147F Chinook helicopter (or a motorcade if weather dictates) for the roughly 80 km journey into the mountains. Japanese security would have a subset of SP agents on whatever transport is used, maintaining close guard of the PM.

For ground transportation, Japan typically brings its own armored vehicles for the principal. The Prime Minister’s official state car is currently a Toyota Century sedan (third generation), with an older Lexus LS 600h also kept as a backup. These vehicles are heavily armored with bulletproof glass and steel plating, offering protection against small arms and moderate explosives. They are part of the PM’s motorcade both in Japan and often abroad. To have these cars available in Canada, Japan must transport them well ahead of the summit. There are a couple of methods: sometimes they are shipped by air using a cargo aircraft – for instance, a JASDF Kawasaki C-2 transport plane could fly an armored limo and possibly support vehicles (like SUVs or vans for the delegation) to Canada. The C-2’s range and payload can handle a direct transpacific flight with mid-air refueling, or a stop in Hawaii/Alaska, carrying heavy equipment. Alternatively, if cost and time permit, vehicles might be sent by sea freight weeks in advance to Vancouver and then railed/trucked to Alberta. However, given security and schedule, an airlift is more likely. Japan has in the past had to rely on foreign heavy-lift (they even showed interest in larger transports like the C-17 for global deployments), but the current C-2 and C-130 fleet can manage summit logistics with careful planning.

The Japanese vehicles, once in Canada, will be integrated into the official motorcade. An armored Toyota Century bearing the Japanese flag will carry the Prime Minister, likely with an SP officer in the front passenger seat. Follow cars (perhaps armored SUVs or sedans) will carry additional security and staff. These vehicles will have Japanese government plates but are operated under permission of the Canadian authorities while here. They are outfitted with secure communications so the PM can stay in touch with his team and even Tokyo while on the move. The motorcade will be led by RCMP traffic units and flanked by Canadian police cruisers or motorcycles, with local police clearing intersections. Some of the Japanese delegation vehicles (such as luggage vans or secondary staff cars) might be borrowed locally or provided by the RCMP motor pool, but the principal’s car is usually Japanese-provided to ensure consistency of security features.

At the summit venue, Japanese security will also arrange for vehicle security sweeps and dedicated parking. The armored car is typically kept in a secure garage or fenced area when not in use, under guard by SP officers. As an extra measure, the delegation may use electronic countermeasure vehicles in the convoy (e.g. vehicles equipped to jam remote explosive triggers or for communications relay). If Japan has such capabilities, they could be deployed, or they might rely on Canadian-provided electronic warfare support that covers all convoys. All these logistic elements – air arrival, helicopters, armored cars – require intricate coordination with Canada’s summit office, the RCMP, and even NORAD. The timing of arrivals is deconflicted among all G7 leaders to avoid congestion at the airport and ensure each motorcade can be securely managed. Japan’s arrival slot will be planned likely around the same time as other Asia-Pacific leaders (possibly around when the U.S. President arrives, etc.), with a tightly secured arrival ceremony or greeting before the PM heads to Kananaskis.

Operating an armed foreign protective detail on Canadian soil necessitates a clear legal framework. Japan’s security officers (SP agents, and any possible SAT operatives or armed diplomatic security) must be granted permission by Canada to carry firearms and use force in protective duties. Typically, this is handled through diplomatic channels and Canadian law governing foreign officials at high-level events. For the G7 Summit, the Canadian government issued a special Privileges and Immunities Order for 2025, which extends diplomatic protections to foreign representatives and their staff during the event. Under this order and standard international practice, the Prime Minister of Japan and his security detail enjoy status similar to diplomatic agents. They have immunity from arrest and are exempt from certain Canadian weapons laws, to the extent required for their official functions at the summit.

In practical terms, Japan’s security personnel would be accredited as part of the official delegation and identified to Canadian authorities ahead of time. There is likely an exchange of diplomatic notes where Japan requests permission for named individuals (SP officers) to be armed for close protection duties. Canadian federal legislation (such as the Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act) provides mechanisms to temporarily exempt such persons from prohibitions on carrying firearms, provided they are performing official duties. The RCMP, as the security lead, runs a deconfliction process: all foreign protective details must register their firearms (make, model, serial number) and ammunition types with the RCMP command. The foreign agents are typically required to carry documentation of their authorization and might be paired with a Canadian liaison officer who ensures local law enforcement knows their identity.

During the summit, any armed Japanese personnel will operate under agreed rules: for example, they may only brandish or discharge a weapon in immediate defense of the protected person’s life, and ideally, Canadian officers handle any use-of-force beyond the inner circle. The RCMP’s protective policing branch often embeds a close protection liaison with each delegation – this officer works with the Japanese SP team to coordinate movements and can also serve as a point of contact if local police have interactions with the Japanese agents. In the event of an incident (e.g. an arrest or a shooting involving a foreign bodyguard), the diplomatic immunity means the individual would not be prosecuted under Canadian law, but in practice such incidents are extremely rare due to careful planning.

It’s worth noting that during major summits in Canada, foreign security teams routinely carry sidearms – U.S. Secret Service agents, British Royalty Protection officers, French Gendarmerie GIGN details, etc., all are armed when protecting their leaders. Japan’s team is no exception, and Canada has long-established protocols to accommodate this while maintaining overall command. Foreign agents do not have police powers in Canada, so if an issue arises with someone other than an immediate threat to their VIP, they are expected to alert Canadian police rather than intervene directly. The legal permission is narrowly tailored: it allows them to protect their principal, not enforce laws generally. All foreign weapons are typically secured when not on duty (for example, stored in safes at the delegation’s accommodations under a dual-key system possibly involving RCMP supervision).

Diplomatic immunity also covers the Japanese security team’s equipment and vehicles – their baggage won’t be subject to normal customs inspections, and their official vehicles can be imported temporarily without hindrance. Canada’s Privileges order specifically grants inviolability of papers and baggage to representatives, which would include sensitive security equipment. Additionally, any Japanese SAT or special operators (if present under other roles) would likely travel under diplomatic passports or official status to ensure they too are covered by immunity. These arrangements are vital to allow Japan’s security officers to function confidently. Canadian officials, behind the scenes, will have a dossier on every weapon and every security officer in each motorcade, and the summit’s integrated command will ensure allied forces are aware of each other’s presence to prevent “blue-on-blue” incidents. This high level of trust and cooperation is a hallmark of G7 security operations.

Japan’s approach to delegation security at Kananaskis 2025 builds on lessons from past summits, both abroad and at home. Reviewing a few relevant cases highlights the evolving tactics and coordination models:

In summary, the pattern across these historic deployments is one of incremental improvement and deepening cooperation. Japan has consistently provided capable close-protection teams for its leaders and, when hosting, has scaled up to protect others too. They have faced down evolving threats (terrorism, protester disruptions, lone attackers) with thorough planning. At Kananaskis 2025, the Japanese will apply all these lessons: rigorous advance work, seamless comms with partners, layered defense (from intel to immediate bodyguarding), and adaptability to the specific environment (mountainous terrain, remote venue). The goal is zero surprises, much as it was in past summits that concluded safely.

Open-source observers can potentially track and verify several aspects of the Japanese security operation around the G7 Summit. These OSINT signatures include:

Together, these OSINT indicators provide a mosaic that can confirm and detail Japan’s protective efforts at the G7. While much of the security operation is secret, the very nature of moving people and equipment internationally creates traces in the open source realm. Observers in Alberta and armchair analysts online will be piecing together these clues as the summit unfolds. The high degree of transparency in democracies and the enthusiasm of spotters mean that even security operations can’t remain entirely in the shadows – a reality well understood by summit security planners, who thus also plan overt show-of-force as a deterrent (knowing it will be seen) while keeping truly sensitive details confidential.

Japan’s contribution to the security of its Prime Minister at the 2025 G7 Summit exemplifies a modern, well-coordinated protective strategy. The NPA Security Police will form the front line around the Japanese leader, backed by the possible quiet presence of special counterterror assets (SAT) if needed. The Cabinet’s intelligence arm ensures that no threat insight is missed in cooperation with Canadian and allied agencies. Logistically, Japan brings formidable resources – from dedicated VIP aircraft to armored limousines – to project a secure environment for its leadership abroad. All of this is done under the umbrella of Canadian law and command, reflecting the deep trust between Japan and Canada.

As past summits have shown, a harmonious integration of foreign protective teams into the host nation’s system is critical for a safe event. Japan’s security officials have prepared extensively, learning from events in Charlevoix, Ise-Shima, Biarritz, Osaka, and beyond. Their focus is not only on the physical safety of Prime Minister Ishiba but also on ensuring Japan can participate fully in the summit’s diplomatic agenda without security distractions.

Open-source intelligence gives us a rare glimpse into this world: through careful observation and public records, we see the outlines of a robust security architecture. From the moment Japanese Air Force One touches down in Calgary to the motorcade’s arrival in the sealed-off Kananaskis “security zone,” every step is the product of bilateral planning and professionalism. In many ways, the security operation is a summit in itself – a meeting of nations’ services working towards the singular goal of protecting leaders and maintaining international peace and security discussions. Japan’s role in this may be understated publicly, but it is undeniably vital and backed by meticulous preparation derived from years of OSINT-observable patterns and experiences.

Editor’s Note: All of this information is sourced from the public domain and logical inference.