Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

The upcoming G7 Summit (June 15–17, 2025) in Kananaskis, Alberta will transform a peaceful mountain resort into the focal point of one of the largest domestic security operations in recent Canadian history. World leaders will convene at the Pomeroy Kananaskis Mountain Lodge, and far from the public eye a RCMP-led Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG) will orchestrate an extensive security blanket over the region. In support, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) is deploying a substantial joint task force – a mission of military aid to civilian law enforcement reminiscent of the 2002 G8 Summit (code-named Op GRIZZLY) held in the same locale, albeit updated for modern threats and sensitivities.

This intelligence brief takes a deep dive into the scale, purpose, and composition of the CAF presence being marshaled for Kananaskis 2025. It provides a detailed breakdown of the units and equipment likely involved – from infantry battalions and armored vehicles on the ground to helicopters, drones, and fighter jets policing the skies. We examine the role of the Royal Canadian Navy in a landlocked operation, the quiet integration of special forces and specialized units behind the scenes, and even the field craft of tracking this operation through open-source means (spotting convoys, decoding vehicle markings, and watching for telltale flight restrictions). Throughout, we reflect on how this event fits into a broader pattern of Canadian domestic security readiness, drawing parallels to past deployments at the 2002 G8 Summit and 2010 Vancouver Olympics, among others.

Rooted in OSINT (Open Source Intelligence), this brief emphasizes that all conclusions herein derive from publicly available data, official statements, and historical precedent – not from any classified material. The aim is an informed analysis suitable for both the general reader and the seasoned security analyst. If there is a touch of dry wit in observing the lengths to which Canada goes to secure a meeting of seven leaders (including tracking the local grizzly bears with radio collars, as happened in 2002), it serves to underscore the mix of serious preparation and hysterical theater inherent to such high-profile operations.

Let’s break down what to expect when the world (and a few thousand of Canada’s finest in uniform) arrives in the Canadian Rockies.

At the helm of summit security is an Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG) led by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). This multi-agency task force is a unified command structure that pulls together federal, provincial, and local resources under one umbrella. The ISSG for Kananaskis includes the RCMP as lead agency, the Calgary Police Service, Alberta Sheriffs, Alberta Conservation Officers, and crucially, the Canadian Armed Forces in a supporting (but significant) role. In essence, the RCMP handles law enforcement and personal protection of VIPs, while the CAF provides unique capabilities and surge capacity that law enforcement alone cannot easily field.

This civil-military arrangement is governed by established protocols. The RCMP, by law, holds responsibility for the security of visiting international protectees and the event site. The CAF’s involvement comes under the rubric of “Aid to Civil Power”, a concept whereby military resources assist civilian authorities upon request in domestic scenarios. That request has clearly been made for the G7. According to a Public Safety Canada briefing, “as the G7 is a designated major international event, security will be provided through the unified and coordinated response of an Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG).” The CAF’s job is to enhance and complement the police-led effort by contributing planning staff, logistics, and specialized operational support – all while remaining visibly under RCMP operational direction to maintain the primacy of civilian authority. The military’s presence may be intimidating but, if you are brutalized, you are more likely to wish to thank the RCMP.

While exact numbers for 2025 are not public (“for operational security reasons, the ISSG and CAF will not be confirming specific equipment or the number of vehicles,” officials say), we can glean a sense of scale from precedent. In the 2018 G7 Summit in Charlevoix (Operation CADENCE), over 2,200 CAF personnel were deployed alongside police. That involved approximately 269 military vehicles and 15 aircraft in support. The 2010 G8/G20 in Ontario saw about 2,800 CAF members supporting security, and the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics (Op PODIUM) mobilized around 4,500 CAF personnel to aid the RCMP-led Olympic Integrated Security Unit. The 2002 Kananaskis G8 Summit remains the high-water mark: Operation GRIZZLY marshaled close to 6,000 troops with “hundreds of vehicles and aircraft” to secure that event – reflecting post-9/11 jitters and the remote, sprawling area to secure.

For 2025’s G7 in the same region, we can expect a deployment on the order of a few thousand military personnel (likely 2,000–3,000+), making it one of the largest domestic operations for the CAF in recent years (surpassed perhaps only by the pandemic response and earlier summit/Olympic missions). The CAF contingent forms a joint task force under Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC), integrated with the ISSG structure. In practical terms, there will be a military headquarters element working closely with the RCMP’s command center – sharing a Common Operating Picture and coordinating resources. (In 2018, for example, a CAF geomatics team was embedded to provide mapping and live updates to all partners.) The military will have its own internal unit organization (often titled “Joint Task Force [region or event name]”), but for the summit’s duration it officially answers to the needs identified by the RCMP.

Beyond scaring the hell out of local residents, the CAF’s mandate in such events is to deploy capabilities that augment security and safety without directly engaging in law enforcement. The dubious official stance in 2018 was that “CAF members did not [conduct] law enforcement activities.” That remains theoretically true – soldiers won’t be arresting protesters or guarding VIPs on the inner perimeter (that’s the job of police and Secret Service equivalents). Instead, the military provides:

It’s worth noting the theatrical element here. The visibility of uniformed troops, armored vehicles, and aircraft is a message unto itself: it says “stay away, you won’t get anywhere near the summit.” Officials openly acknowledge that a visible security footprint is meant to reassure locals and dissuade bad actors. Of course, they balance this with propagandistic community relations – the ISSG has “outreach teams” to (dis)inform residents and “ensure the community feels supported and reassured” even as security ramps up. (Translation: We know it’s a lot of camo and guns around your quiet town, but don’t be alarmed.) The RCMP and military spokespersons have been tight-lipped about specifics, but have warned the public to expect an “increased security presence” including seeing military members working alongside police.

In summary, the CAF’s role under the ISSG is force multiplication – lending resources that help cover more ground and respond to more contingencies than the RCMP could alone, all coordinated through a unified command. The military brings depth (extra boots and vehicles), breadth (surveillance from air and ground), and niche capabilities (engineering, CBRN, etc.) to the security plan. Moreover, in the unlikely case that a serious incident were to occur, the CAF would unoficially take the lead – especially if the attack was kinetic in nature. Next, we’ll break down who exactly those boots and vehicles belong to – the composition of the force that Canada’s military is likely dedicating to this summit.

Although officials won’t release troop counts, an estimated order of battle for the CAF G7 task force can be sketched out from open sources and past patterns. The deployment will draw primarily from units in Western Canada, given the proximity of major bases in Alberta, with augmentation from specialized units based elsewhere. Here’s how it likely breaks down at the battalion and squadron level:

In aggregate, these components form a sizable joint force. If we sum notional numbers: an infantry battle group of ~500–700, an armored squadron ~100, engineers and signals ~150, health services ~50, service support ~200, air crews and support ~200, special ops ~100+, plus MPs and odds-and-ends, we are comfortably in the 1,500–2,500 range. Indeed, over 2,200 CAF members were used in 2018, and Kananaskis 2025 likely requires equal or more given the challenging terrain.

It’s also important to emphasize the joint nature: Army provides the bulk of personnel; Air Force provides critical capabilities (and many personnel in the form of aircrews, technicians, air defenders); Navy provides specialized teams and reservists. All are under one integrated command for this event. In practice, a brigadier-general or colonel will be the Task Force commander liaising with the RCMP Gold Commander. (In 2002, a Brig.-Gen. – BGen Fenton – commanded the CF contingent. In 2018, CJOC stood up a Joint Task Force with a named commander as well.) Their headquarters will mirror the ISSG structure – likely co-located or in constant communication with the RCMP ops center in or near Kananaskis.

Finally, to manage expectations: the majority of CAF personnel will operate behind the scenes. Many will be in logistics hubs or standby locations (e.g., an assembly area outside the restricted zone, or at CFD Calgary barracks or similar). Only a fraction will be highly visible at any given time (e.g., manning a checkpoint or patrolling a ridge in uniform). The aim is to have enough force immediately available without making the resort look like an outright warzone. Achieving that balance – robust security without undue disruption – is a stated goal of planners (“the least amount of impact on people,” as the ISSG spokesperson put it). Of course, “least impact” is relative when you’re effectively militarizing a chunk of Alberta’s backcountry for a week. But it means you won’t see soldiers lining the red carpet at the lodge; they’ll be on the periphery, literally and figuratively, supporting the operation – and some of them will be very well-hidden in plain sight.

Having outlined who is coming, let’s look at what they’re bringing. The next section details the vehicle fleets and major equipment the CAF will field – from the formidable LAV 6.0 armored vehicles to the workhorse trucks and high-tech surveillance gear.

One of the most visible aspects of any military deployment is its vehicles. Over the past few weeks leading up to the summit, Alberta residents have already caught sight of long convoys hauling green military hardware southward from Edmonton to the Calgary area. Although officials refuse to list exactly which vehicles (“no confirmation of specific equipment or number of vehicles” as per the ISSG’s statement), open sources and eyewitness accounts give us a good idea. Based on 2018’s figures (269 military and rented vehicles were used) and the known inventory of local units, here’s a breakdown of key vehicle types likely in play and their roles:

In terms of deployment locations, many of these vehicles will be staged at various rings around the summit site. The innermost perimeter (the “red zone” immediately around the resort) likely won’t have CAF vehicles parked visibly – that’s mostly RCMP close protection and barriers. Just outside that, at command posts and quick reaction force locations, you might find a cluster of LAVs and TAPVs ready to move in if needed. Further out, at each road checkpoint miles away, a TAPV or even a LAV could be present with a section of infantry to secure it. Convoy trucks will be mostly on the highway corridors (Trans-Canada Highway, Kananaskis Highway 40) during the lead-up and teardown phases, less so during the core summit (when all heavy moves pause). At least one large vehicle park or temporary camp will be established – possibly at the Calgary end (e.g., at a Canadian Forces facility in or near Calgary like the old Currie Barracks or even at HMCS Tecumseh grounds) and one closer to Kananaskis (they might use Nakiska ski area parking or the Delta Lodge helipad area as a staging ground for heli operations and vehicles). In 2002, several self-sustained camps were dotting the area – expect a repeat with modern containerized camps for troops and their kit.

To illustrate the mix of vehicles, here’s a concise list of the primary vehicle types and their anticipated roles at the G7 Summit:

While the above focuses on the army’s ground vehicle set, an equally important fleet is in the skies. Thus, we now turn to the aerial component, which provides a bird’s-eye view and rapid transport capability for the summit security – from helicopters buzzing over mountain ridges to fighters roaring above (and sometimes startling residents, as happened in 2002).

Securing a summit is a three-dimensional job, and the airspace might be the most sensitive dimension of all. Nothing can travel faster or further than an aircraft, which is why a significant portion of the security effort is dedicated to controlling the skies over Kananaskis. Canada’s approach to summit air security is multi-layered, involving restricted airspace, dedicated military aircraft patrols, and integration with NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command) for early warning and interception. Let’s break down the aerial assets and strategies:

Restricted Airspace (No-Fly Zone): For the summit period, Transport Canada (in coordination with NAV CANADA and NORAD) has established two temporary no-fly zones over Kananaskis and the broad surrounding area. In 2002, that zone was a 150-km radius around the summit, a huge area reflecting heightened post-9/11 caution. It was reported that a 150-km radius no-fly was implemented at summit time, effectively clearing the entire region of any non-authorized aircraft. In 2025, the two no-fly zones shown below are in place.

These have been published via NOTAM (Notice to Airmen) and means all civilian flights, private or commercial, are either barred or tightly controlled in that zone for the duration. Commercial airlines normally overflying at 35,000 feet could be routed around or above the restricted ceiling. Light aircraft, helicopters, and especially drones will be completely prohibited. In fact, an explicit drone restriction is in place – in 2018, drones were specifically banned in the summit area by Transport Canada (with public advisories given). Violators risk interception by fighters or police helicopters, and hefty fines or worse.

On a related note, the mention of NORAD long-range radar support in 2018 implies that fixed radar coverage was beefed up. NORAD already has robust radar coverage of Alberta (through military/civil ATC radars and the North Warning System’s southern extensions). But for low-level threats (like small planes or drones), a deployable radar might be used. The CAF has systems like the NASAMS radar or tactical radars that can cover gaps in mountain valleys. In 2018, an AN/TPQ-49 counter-mortar radar was reportedly used to watch the low-level airspace, an innovative adaptation of equipment to pick up slow, low aerial objects.

On the flip side, anti-drone measures will be in place. This is critical in 2025, as small commercial drones could be used maliciously (to spy, or conceivably to carry a payload). The CAF’s Electronic Warfare teams (21 EW Regt and others) very likely have drone detection and jamming equipment on site. This could include RF scanners that pick up drone control signals and jammers like DroneDefender rifles or larger systems to knock down or take over rogue drones. While classified, one can reasonably assume that no unauthorized drone will last long in the Kananaskis airspace – either it’ll be forced down by electronic means or even shot down if necessary. (During the 2018 G7, authorities did intercept a few nuisance drones, according to media reports, though without much fanfare.)

CP-140 Aurora and Other Fixed-Wing ISR: The mention of a CP-140 Aurora maritime patrol aircraft being part of the security toolkit is intriguing. The Aurora, essentially a Canadian P-3 Orion, is outfitted with advanced long-range sensors including mapping radar and electronic signal detectors. In a domestic summit, an Aurora could orbit at high altitude (20,000+ feet), acting as a broad-area surveillance platform. Its radar could map vehicles moving on remote roads tens of kilometers away, and its electronics suite could eavesdrop on radio communications in the area (helpful to identify unlicensed transmissions or any threat manifesto being broadcast). In Charlevoix 2018, the CAF noted they flew over 125 hours and conducted 225 hours of “observation and analysis” as part of the summit – some of that was likely Aurora or other aircraft time, since few other assets have that endurance. The Aurora’s presence would be completely invisible to the public (it’s high up, and one might mistake it for any airliner if seen at all). But internally, it can feed intel to ground commanders in near-real time. Also, if something like a radio jammer needed to be deployed, an Aurora can serve as an aerial relay for comms to unaffected units.

Another platform to mention is the possibility of satellite support. Being OSINT-driven, we note that unclassified commercial satellites will certainly be imaging the summit (journalists and hobbyists often task imaging satellites to get overhead pictures of summit layouts). On the military side, Canadian and allied intelligence satellites will keep an eye out for any larger aggressor moves (though an attack via missile or such is extremely unlikely, it’s standard to have space-based early warning just in case). This is all far above the head of the average onlooker, but it’s part of the comprehensive security net – “eyes in the sky” also includes eyes in space.

VIP and Transport Aircraft: In addition to combat and patrol aircraft, many transport planes will be involved in ferrying personnel and equipment before and after the summit. The Royal Canadian Air Force has CC-130 Hercules and CC-177 Globemaster aircraft that may have flown in heavy equipment to Calgary or a nearby base. For instance, it wouldn’t be surprising if a Globemaster carried armored vehicles or extra helicopters as cargo into Calgary ahead of time. These flights are usually not publicized, but plane-spotters can sometimes catch their tail numbers on ADS-B logs arriving at odd hours. Furthermore, the summit involves heads of state arriving on their national aircraft. Calgary International Airport will likely host an impressive lineup: Air Force One (USA’s Boeing VC-25 or 747), France’s Airbus A330, Germany’s A340 or new A350, Japan’s government 777, Italy’s Air Force jets, the UK’s RAF Voyager (A330), and Canada’s own CC-150 Polaris used by the Prime Minister. Each of these flights will get special handling – they often come in staggered, and RCMP along with CAF liaison officers will greet and transfer the principals. The arrival/departure phase is itself a mini-operation, with security at the airport beefed up. The CAF’s role here might include Air Movements personnel (to help park and service aircraft), air traffic coordination (CFATC works with NAV CANADA for VIP movement), and ceremonial guard perhaps (though usually that’s RCMP/Canadian Guards for official welcome). A small aside: the U.S. typically brings additional planes like C-17s carrying the presidential motorcade vehicles (the “Beast” limo, Secret Service SUVs, maybe even Marine One helicopters). These will also land in Calgary. It’s a logistical ballet – one that is planned to the minute.

Airspace Control Tactics: How do all these pieces tie together? At the top, there will be an Air Component Coordinator (likely from RCAF) embedded with the ISSG command, ensuring that all air operations (military and civilian) are deconflicted and responsive to security needs. A special air operations center may be established, or NORAD’s Canadian Regional HQ will take on that function. They’ll enforce the restricted zone by having radar track everything that moves. If a plane pops up that shouldn’t be there, steps escalate: first, radio contact attempt by ATC/NORAD; if no compliance, a CF-18 is vectored to intercept; failing compliance, rules of engagement allow force (which in the worst case could mean a shootdown to protect the summit, a grave decision that thankfully has never had to be made in these events). For lower, slower threats like a Cessna or a drone, a helicopter or even ground-based police might handle it (for example, RCMP could deploy a team to physically locate and stop a drone operator if detected). The layered defense also involves Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs) which are published to pilots – so any pilot who checks NOTAMs knows to avoid the area, meaning if someone does enter, they either missed the memo (and will be quickly escorted out by fighters) or they have intent to cause trouble.

We should mention civil aviation coordination: Calgary’s airspace is busy, and it’s within 150 km of Kananaskis. The restrictions have a graded scheme: an inner circle (25nm) of no flights except military/police; an outer ring up to (80nm) of flights allowed above a certain altitude or with flight plans approved (so that airline traffic to Calgary can continue but maybe with altered approach paths). Also, medevac or emergency flights can be allowed case-by-case, which is typical – the NOTAM will have contact info for any urgent transit needed (like an air ambulance could request to cross, and they’d coordinate fighter escort if necessary).

With the air and ground domains covered, we turn our attention to the domain one might least expect in Alberta’s Rockies: the maritime domain. How does the Royal Canadian Navy factor into a mountain summit? We’ll explore that next, including bomb teams, divers, and even a naval reserve presence far from the sea.

Kananaskis, Alberta is about as far from the ocean as one can get – nestled in the Rockies, hundreds of kilometers from any coast. On first glance, there’s no obvious role for the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) in a G7 summit here. Yet, Canada’s military operations are always joint, and the RCN has carved out supportive roles even in landlocked events. For the 2025 G7 Summit, the Navy’s involvement will be modest but specialized, focusing on areas where naval expertise or resources complement the overall security effort.

Naval Tactical Operations Group (NTOG): The NTOG is an elite unit within the Navy that specializes in boarding operations and counter-terrorism at sea (essentially, Navy special forces, often working with JTF2). While boardings won’t be needed in Kananaskis, the skill set of NTOG operators (stealth, close-quarters combat, surveillance) overlaps with requirements of summit security. It’s plausible that a small team from NTOG is attached to either JTF2 or the RCMP’s counter-terror teams on standby. They might, for example, augment the team securing any water source or utility facility – say there’s a reservoir or hydro dam feeding the area, NTOG could help secure it given their comfort operating around water and confined structures. Or they might simply serve as an extra pool of highly trained personnel for rapid response in case of a complex attack. Historically, NTOG (or its precursor, the Naval Boarding Party teams) were present in Vancouver 2010 to help with waterside security. In Alberta 2025, they could be repurposed to augment land-based special ops.

Clearance Divers and EOD: The RCN’s Fleet Diving Units (Atlantic and Pacific) contain Canada’s top Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) experts, particularly for underwater and improvised devices. These navy bomb techs are often called upon to assist domestic security events. Why? Because bombs can be hidden anywhere – in 2010, divers checked the undersides of piers and ships; in Kananaskis, they might check bridge abutments, culverts, or even the bottoms of the ornamental ponds at the resort. If the venue has a water intake from a lake or river, clearance divers could ensure no one has tampered with it or planted something. They also bring expertise with chemical/biological weapon detection underwater. Given the summit’s remoteness, any bomb threat might actually be more likely on a route (like an IED on a roadway) than in water, but the CAF will have a combined EOD team ready – likely Army engineers for general devices and Navy clearance divers for any tricky or watery ones. The divers also have portable sonar and robots that could be used if, for instance, something fell into a lake that needed investigation. The RCN will count these EOD capabilities as part of its contribution, even if to onlookers it’s indistinguishable from any other bomb squad present.

Naval Reserve & HMCS Tecumseh: A unique element is HMCS Tecumseh, the Naval Reserve division located in Calgary. This is essentially a Navy base without any ships – a training facility and administrative hub for reserve sailors. For the G7, Tecumseh is likely being used as a support location. It could serve as a staging area or command post for some ISSG activities. For example, credentials processing or briefings for arriving security contingents could happen there in the lead-up (away from the public eye). It provides a secure location in Calgary with infrastructure (communications, offices, and a drill hall) that can be repurposed for coordinating the operation. Naval Reservists from Tecumseh and possibly from other Prairie reserve units (like HMCS Tecumseh’s counterparts in landlocked cities – e.g., HMCS Unicorn in Saskatoon, HMCS Chippawa in Winnipeg) might volunteer or be called up to assist. What can they do? Many Naval Reservists have trades like Logistics officers, Public Affairs, or Intelligence analysts in their ranks – these skills are quite useful in an event security context. A reserve logistics officer could help manage the flow of supplies; an intelligence reservist might join the all-source analysis cell sifting through information for threats; a public affairs reservist might help staff the media centre or community outreach (explaining to local residents what all the military activity is about). These are roles where extra hands are always welcome, and tapping reservists is a cost-effective way to surge manpower.

Additionally, we might see Naval reservists directly in some community-facing roles. For instance, the ISSG often sets up an information centre for the public (indeed news said an info centre opened ahead of the summit). Reservists, who are local citizens themselves, could staff such a centre or be liaisons to the town of Canmore and Banff. It’s a smart PR move to have a local sailor or soldier be the face that communicates with locals about road closures or safety measures – they understand the community and speak the language (not literally different from the rest of Canada here, but meaning they can relate better).

Naval Vehicles and Boats: In 2018, the RCN tallied 7 vehicles/boats in use. What were those? Possibly a couple of Rigid-Hull Inflatable Boats (RHIBs) deployed on the St. Lawrence River near La Malbaie (to patrol the shoreline by water) and some trucks towing them. Kananaskis doesn’t have large navigable waters requiring RHIBs. The nearest might be Barrier Lake (a reservoir on Kananaskis River) or Spray Lakes. It’s conceivable a small boat or two could be used on Barrier Lake if there’s concern of someone using the water to approach or place something (but that scenario is far-fetched given the isolation). More likely, the “vehicles” counted will be the Navy’s trucks and possibly the dive team’s gear truck. The clearance dive team might bring a Dive Support Vehicle, essentially a big truck or trailer outfitted for their equipment. NTOG operators might have a pickup or SUV assigned. So the RCN’s vehicular footprint might be a handful of plain trucks rather than anything exotic.

Integration with Other Units: The navy folks will be embedded in joint teams. For example, a clearance diver might work alongside an Army EOD tech and an RCMP bomb tech as a composite explosives team. Naval reservists in an ops centre will answer to whoever’s in charge there (maybe an Army Major). The key point is their unique skills fill gaps. If one thinks of the summit like a big puzzle, the Navy pieces fill some of the small but crucial gaps (like “who can handle potential underwater threats?” or “who can provide extra comms and intel analysts?”).

One interesting note: the name “Integrated Safety and Security Group” (ISSG) hints that it’s not just security in terms of stopping bad guys, but also safety – this covers things like fire, rescue, medical, and even wildlife management. In 2002, dealing with wildlife (e.g., grizzly bears literally wandering into the secured zone) was a real challenge. The Alberta Conservation Officers are leads on that, but perhaps the Navy’s experience with marine wildlife? (Okay, we’re stretching – unless a rogue orca shows up in the Kananaskis River, the Navy won’t be needed for wildlife.) However, fun fact: in 2002, they collared about 8 grizzlies in the area to monitor and keep them away from the summit. In 2025, they have a “Wildlife Management Plan” as part of security again. If they repeat using tracking collars or drones to watch animals, that’s more in the realm of parks and conservation folks, but military may assist with tech or manpower.

Naval Role in Dignitary Protection: Typically, RCN doesn’t guard VIPs (that’s RCMP and host nation secret service units). But the RCN’s Naval Security Team (NST) concept – which is a deployable team to protect naval assets in foreign ports – has skills in access control and security patrols. Some personnel from that background could be used to guard critical infrastructure in the area (for instance, the summit’s power substation or communications hub). They are essentially acting as additional military security guards in those contexts.

Wrapping up RCN’s part: It’s fair to say the Navy’s involvement is the smallest slice of the CAF pie here, yet it exemplifies the “no stone unturned” approach of Canadian security planning. If there’s even a hypothetical angle involving water or explosives or an extra command post, the Navy has something to add. It also demonstrates joint unity – the idea that Army, Air Force, and Navy all contribute to national security events. For the average person in Kananaskis, the Navy’s presence might not be noticed at all (unless you run into a friendly Naval Reserve officer at the information center). But rest assured, a few sailors in army camouflage (yes, Navy personnel often wear Army camo uniform on land ops to blend in) will be there, with dive kits and maps in hand, quietly doing their part.

Next, we move from the domain of the obvious (tanks, jets, and police on the ground) to the realm of the unseen operatives. The summit undoubtedly has a silent backbone of special forces, electronic wizards, and intelligence teams ensuring nothing catches security off-guard. Let’s shed some light on those shadowy participants.

Behind the cordons and visible displays of force lurks another layer of summit security – the specialized units that remain out of sight. These include Canada’s special operations forces (SOF) and various high-tech support teams that are rarely acknowledged publicly. They are, in effect, the insurance policy against worst-case scenarios. While the RCMP and regular military units handle routine security tasks, these elite teams prepare for extreme threats: sophisticated terrorism, hostages, CBRN incidents, cyber attacks, and so forth. Here’s an overview of who’s almost certainly there in the shadows, based solely on open information and precedent:

To sum up, the summit’s unseen defenders form a web of last-resort capabilities. They hope to never be needed overtly, but they are poised to respond to the unimaginable. They train intensively in the run-up – often doing joint exercises on similar terrain or rehearsing specific scenarios. For instance, JTF2 and ERT might have run a mock exercise of storming a hostage-held chalet, or CJIRU might have drilled a chemical attack response at an empty building.

The public and media tend to focus on the overt security (fences, checkpoints, uniforms). But rest assured, in the alpine forests around Kananaskis, there are also camouflaged figures lying in observation, high-powered rifles and spotting scopes at their side, quietly scanning for threats that no one else would see. There are rooms where headphones-clad analysts listen to signal static for anomalies. There are vehicles that look nondescript parked on a ridge that are in fact filled with commandoes ready to deploy. It’s the quiet professionalism of these units that allows the visible security to remain comparatively measured. They are the insurance policy, and knowing they’re there allows planners not to turn the summit into a complete armed camp overtly.

Now, after covering all these layers of security, one might wonder: how can an ordinary observer make sense of it all? That leads us to a more hands-on section – field tips for tracking and identifying the security measures through open sources. In the next part, we will switch perspective and provide an OSINT practitioner’s guide to spotting convoys, decoding vehicle markings, and following the aerial ballet via public data.

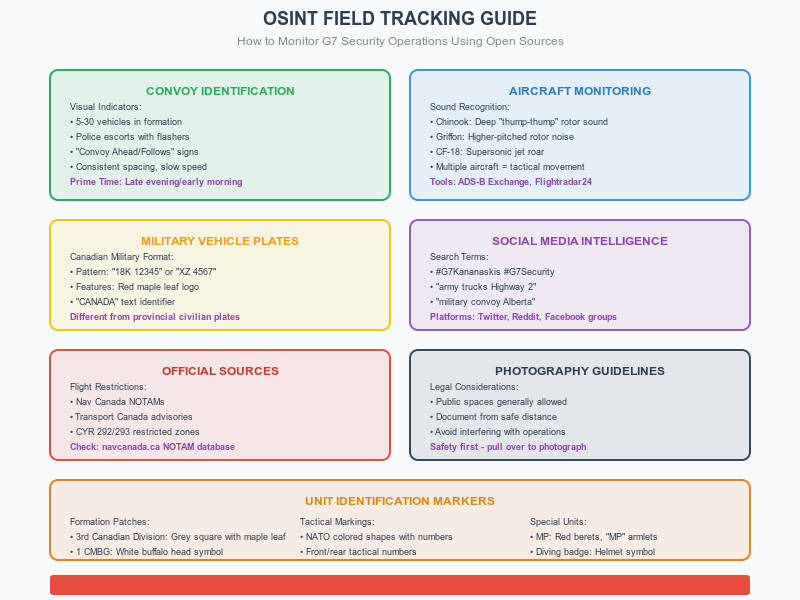

For local residents, journalists, or curious onlookers, the G7 Summit security operation provides plenty of clues and signatures that can be observed in the open. Since all the information in this brief is derived from open sources, it’s fitting to share some techniques on how one might track such a large deployment without any secret access. This is security in plain sight, if you know what to look for. Below are field tips on spotting military convoys, understanding vehicle markings, and monitoring flights and airspace – all through legal, public means.

1. Military Convoys on the Road: The movement of vehicles from bases to the summit site is hard to hide (short of transporting everything by rail at night, which is impractical). Indeed, public advisories have been issued about convoys from Edmonton to Calgary between May 15 and the start of the Summit. If you’re along Highway 2 or Highway 1 in Alberta during late evenings, keep an eye out for lines of military vehicles. Indicators of a military convoy include: lead and tail escort vehicles with flashing lights and “Convoy Ahead” / “Convoy Follows” signs, a grouping of 5 to 30 vehicles driving closely with consistent spacing, often at or below the speed limit. The convoys tend to move in darkness or very early morning to minimize traffic interference, but they still use headlights (usually in normal mode, not black-out mode, since these are public roads). Another sign is the presence of Military Police or police cruisers at intervals, helping block intersections as the convoy passes – if you see cops waving cars aside on a highway at night and then a stream of green trucks, that’s exactly what’s happening.

If you manage to see the vehicles up close, you’ll notice most have a unique license plate. Canadian military vehicles often use a pattern like “XZ####” or a letter-digit format with a small Canadian flag, or simply a serial number stamped in metal. For example, a standard military plate might say something like “18K 12345” with a red maple leaf logo. This differentiates them from Alberta commercial plates. Larger vehicles like LAVs won’t have a normal plate but instead stenciled numbers on the hull. Don’t expect the military to announce “we moved 40 LAVs today,” but local media has quoted officials acknowledging a “substantial number of military vehicles” on the move – so if you see dozens, that’s in line with expectations.

An OSINT enthusiast might track these convoys by crowd-sourcing sightings: checking local social media (Twitter, Facebook community groups) for posts like “Saw a long line of army trucks on Hwy 2 tonight!” In fact, such posts already exist – e.g., one might find a Reddit thread or FB comment about hearing Chinooks or seeing “14 Chinooks and 100 Griffons” (though that particular claim on social media sounds exaggerated, it indicates people notice). Using hashtags like #G7 or #abtraffic might surface some observations.

Photography: If you photograph a convoy, make sure you’re safe/legal (pull over, don’t drive and shoot). Those photos can later be analyzed to count vehicles and types. In 2010, railfans actually spotted trains carrying armored vehicles to Vancouver – nothing so far indicates rail for this G7, but it’s wise to watch rail lines from Edmonton too, just in case heavy gear was loaded on flatcars.

2. Decoding Vehicle Markings and Uniforms: Each military vehicle often bears unit insignia and tactical markings. On Canadian Army vehicles, you might see a formation patch – for 3rd Canadian Division (Western Canada) this is a French grey square with a maple leaf (or the classic “III” markings), and brigade/unit indicators. For instance, vehicles from 1 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group might have a white stylized buffalo emblem (the symbol of that brigade). There’s also sometimes a small plate on the front with numbers like “41C” or “12▼” etc., which harken back to NATO marking conventions (denoting unit within a formation). These can be arcane to decipher without a cheat sheet, but if you see a vehicle with a certain symbol repeated, you can guess those vehicles are from the same unit. For example, a convoy where each truck has, say, a red square with “1” might imply 1 Engineer Regiment, whereas a blue triangle might be signals – these are just illustrative, actual Canadian symbols vary and often use color shapes to denote brigade and battalion.

Soldiers themselves may have unit patches on their uniforms. On newer Canadian CADPAT uniforms, often the only visible patch is the Canadian flag on the shoulder. Many wear the national flag and their rank/name, but not much unit identifier to untrained eyes. However, specialized units might have unique uniforms: e.g., Military Police wear red berets or MP armlets when on duty – if you see someone with “MP” on their arm or a red beret, that’s a military police officer. Special Forces (JTF2/CSOR) won’t advertise who they are; they might even wear civilian clothes or plain green without obvious badges to blend with regular troops. Navy clearance divers might wear a diving badge (a little insignia with a diver’s helmet) or naval rank slip-ons (which have an anchor symbol), but again if they’re joint with Army, they might use generic uniforms.

3. Watching the Skies – Identifying Helicopters and Aircraft: Summit prep has already involved military aircraft moving into position. To the naked eye or ear: Chinook helicopters have a very distinct low-frequency “thump-thump” rotor sound; if you hear what sounds like a distant heavy woomp-woomp, that’s a Chinook likely. They are larger and tandem-rotored, often flying in pairs. Griffon helicopters have a higher-pitched rotor sound and often fly lower; they might be seen patrolling valleys; they sometimes have bright searchlights or even FLIR pods visible. Locals in Cold Lake reportedly saw an uptick of helo activity (with someone claiming “14 Chinooks, 100 Griffons” tongue-in-cheek on social media heading to Kananaskis) – the realistic numbers are smaller, but indeed multiple aircraft will be deployed. You might catch them visually in daytime transiting (a formation of 3 or 4 helicopters line astern is a giveaway of a tactical move).

For fixed-wing planes: A CF-18 Hornet is audible as a roar if it’s low, but they often stay high. Contrails in CAP patterns (circular or racetrack patterns) could be noticed if conditions allow – a keen observer with binoculars might spot fast jets leaving contrails in loops near the area. If the weather is clear, you might even see their glint if they bank.

ADS-B tracking: The modern OSINT enthusiast’s tool of choice is flight tracking websites like Flightradar24 or ADS-B Exchange. Many military aircraft have their transponders on for at least part of their flights (though sensitive ones can switch off or use anonymized IDs). For example, in previous events, some RCAF aircraft used the callsign “CFC” (Canadian Forces) followed by a number, and those sometimes appear on trackers. A CP-140 Aurora might show up with a Royal Canadian Air Force registration if flying overtly. Some CH-146 Griffons operating domestically have been seen on trackers broadcasting under hex codes, sometimes even with labels like “RESCUE” or just an aircraft number. If you monitor ADS-B Exchange (which doesn’t filter mil aircraft as strictly as FR24 does), you may catch some flights. In the days leading up: look for unusual RCAF transport flights into Calgary (e.g., a CC-177 Globemaster might appear with callsign CFC2730 or similar). During the summit, check for any “Tanker” or “Fighter” callsigns – often, NORAD fighters might not broadcast, but their air refueling tankers do (callsigns like “HUSKY” or “COBRA” for Canadian tankers or “PETRO” etc. for American). If you see a tanker orbiting near Kananaskis on ADS-B, that strongly implies fighters are up (they refuel from it). Sometimes the fighters do appear as anonymous targets on ADSB as well (just an aircraft type code and altitude).

Also, watch for the flurry of VIP diplomatic flights. Many of these are publicly trackable. For instance, one could track Air Force One’s trip (which often disappears on final approach for security, but its departure from Washington is usually noted). In 2018, plane spotters tracked all the G7 leaders’ jets arriving in Quebec. We can expect the same interest in 2025. If you’re near Calgary airport on arrivals day, you could identify each national plane by its livery: Japan’s white with red stripe 777, France’s “République Française” A330, etc. Those are not covert at all – they typically get media coverage too.

4. Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs) and Notices: As an OSINT practitioner, you can actually read the NOTAMs for the summit airspace restrictions. Transport Canada or Nav Canada will publish these a few days in advance. They’ll say something like: “CYRXXXX (a restricted area) in effect from surface to FL XXX within radius Y of coordinates (the summit) during these times. No aircraft except auth by ATC/police. Emergency and military excepted.” Checking Nav Canada’s NOTAM database or using an international source like the FAA’s NOTAM system (the FAA often echoes Canadian TFRs, especially if near US border) will yield the exact boundaries. By comparing that to a map, you can visualize the restricted zone. If you see that it goes, say, up to 18,000 feet, that means commercial overflights above that might still occur. If it goes to “unlimited” (space), they want everyone out. This can give a clue to how worried they are about high-altitude threats.

Additionally, keep an eye on local airfields: the NOTAMs may show closures of small airports or helipads in the area. It’s common to close nearby backcountry airstrips and require any plane that needs to come close (like firefighting aircraft if a wildfire happens, or medical helicopters) to coordinate specially.

5. Traces of Special Ops: These are harder to directly observe without being intrusive (and one should not trespass or interfere if it violates the law, obviously). But sometimes the presence of special forces leaves subtle clues. For example, increased off-hour activity at certain military facilities: did anyone notice unusual nighttime movements at Calgary’s base or the sound of gunfire at a normally quiet range (could indicate JTF2 practicing)? These are anecdotal. If one had a police scanner (many comms are encrypted nowadays), you might catch call signs or units mentioned that hint at special teams. For instance, if you hear “Atlas” or other known JTF2 code words on an unencrypted channel by accident (though highly unlikely, they tend to use secure comms).

Photographically, special forces generally avoid being photographed, but occasionally a long telephoto could catch a glimpse of unidentifiable but non-standard folks – like individuals in civilian SUVs with tactical gear inside, or teams of guys in full kit moving in remote zones. Drones (civilian camera drones) could theoretically try to film around the area, but remember drones are banned and doing so could get one in serious trouble. It’s not advised to try to play cat-and-mouse with security just to get a peek; they will assume any drone is a threat.

Remember, however, that for the most part, filming individuals in public spaces is generally lawful in Canada and can be protected under Section 2(b) of the Charter, especially when documenting police or military personnel performing official duties. However, during high-security events such as summits, authorities may attempt to restrict filming through controlled zones or invoke obstruction laws. While you are not typically required to comply with informal demands to stop filming, use judgment and do not physically resist if an officer attempts to provoke you. If officers attempt to detain you or seize your equipment without lawful authority, document the incident thoroughly—it may form the basis for a Charter challenge or complaint.

6. Public Documentation and Clues: Public Safety Canada sometimes releases after-action reports or budgets which give hints. For OSINT, some documents are already revealing: e.g., a parliamentary committee note mentioned $45.4 million advance funding for RCMP security planning. Such documents show the seriousness and scale (tens of millions on security). They also list partners and roles, confirming the integrated approach. As OSINT, one could monitor government contracting sites – for instance, contracts for “temporary fencing rental in Kananaskis” or “catering for military camp” might have been posted months ago. Local news is a gold mine: the Rocky Mountain Outlook, Cochrane Eagle, CBC Calgary have all published tidbits such as “information centre opens” or quotes from ISSG spokespeople about patrols. Collecting these provides pieces of the puzzle to confirm what units are present and what measures are taken.

7. Visible Ground Measures: If you are physically in the area (in compliance with all laws), you might notice other signs: camera towers (temporary pole cameras with panoramic viewing, possibly mounted on trailers), new signage (like “RCMP checkpoint ahead” signs covered until use, or detour signs stacked ready to deploy), and personnel pre-positioning (for instance, groups of police and soldiers at hotels in Calgary days before moving to site – they have to sleep somewhere). Sometimes hotels in Calgary or Canmore get fully booked by security – a local OSINTer might note the unavailability of hotel rooms and infer that’s the security contingent lodging. Also, unusual combinations of uniforms: e.g., an Army soldier and an RCMP officer having coffee at Tim Hortons together in Canmore – that’s a telltale ISSG pairing right there.

One can also watch power and telecom: extra generators or mobile cell towers might be brought in to handle communications. If you see a Rogers or Telus COW (Cell on Wheels) tower in Kananaskis that wasn’t there before, likely it’s to boost signals for security and VIP needs (and also jam-proof comms because they can control that network slice).

8. Tracking Protests and Unusual Activities: Not all OSINT is about official forces – tracking the movements of protest groups or suspicious actors is something authorities do, but open-source enthusiasts can do similarly via social media. Are any activist groups planning to try to reach Kananaskis? If yes, one might see chatter on Twitter about meet-ups or bus trips from Calgary. Historically, Kananaskis’ remoteness deters large protests (in 2002, most protest was in Calgary far away). But any sign of organized activity could then correlate with security redeployments (e.g., if a protest camp pops up in Canmore, watch for more police moving there).

In summary, there is a lot an observer can glean: counting vehicles, identifying aircraft, reading official notices, and following local media/social media all contribute to a comprehensive open-source picture. And indeed, that’s how this very brief has been compiled – by collating those open hints into a narrative. It underscores a point: while operational details are kept classified, the broad strokes of an operation this size inevitably show in the open. The Canadian approach counts on the fact that while people see the pieces, they may not be able to put it all together easily, and any truly sensitive specifics (like exactly where JTF2 is, or the encryption keys of comms) remain secret.

As we peer through the OSINT lens, we can appreciate the enormity of the effort and also the transparency paradox: The government won’t confirm numbers or gear, but here we have largely deduced them through observation. This leads into a final analytical discussion: why such secrecy in details, how this all fits into Canada’s evolving domestic security doctrine, and the interplay of visible deterrence vs. transparency in these operations. We conclude with reflections on the nature of Canada’s summit security – the performance aspect and the genuine protective mission.

Canada’s deployment of its military for the Kananaskis G7 is not a one-off improvisation; it’s the product of two decades of refining domestic security operations for major events. Comparing 2002’s G8, 2010’s Olympics, 2018’s G7, and now 2025’s G7, we can trace an evolution in strategy, capabilities, and perhaps philosophy regarding large-scale security at home.

In 2002, the G8 Summit in Kananaskis (Operation GRIZZLY) was unprecedented in scale at the time. Coming just months after 9/11, the security posture was maximalist – nearly 6,000 troops, fighters constantly overhead, missiles deployed, and every imaginable contingency braced for. The summit site was turned into a fortified camp and airspace into a bubble. That operation taught many lessons about interagency coordination. A post-summit review lauded how well the RCMP, military, and others gelled despite not having a precedent, but also noted areas to formalize. One outcome was better frameworks for joint command – later codified in MOUs (Memorandums of Understanding) between DND and Public Safety so roles are clear next time. The 2002 success (no incidents, summit went smoothly) set a template that can militarize a remote area effectively, but also raised questions: was it too much? Did it represent an over-militarization?

By 2010, Canada had two huge events: the Vancouver Olympics and the Toronto G8/G20 (held sequentially). The Olympics (Op PODIUM) saw about 4,000-4,500 CAF personnel integrated with police. This was a massive joint deployment with venues in city and mountains (Whistler), involving RCN warships in Vancouver harbor, a full NORAD air defense plan, and even foreign contributions (U.S. and others provided some assistance). The G8 in Huntsville and G20 in Toronto (June 2010) under Op CADENCE similarly used ~2,800 CAF members, though in Toronto the military took a more backseat role (the policing presence was far more visible, and CAF mostly provided behind-scenes support and a few assets like a surveillance aircraft, perhaps because an overt military presence in downtown Toronto would have been politically sensitive). These 2010 experiences highlighted graduated response: showing a lighter footprint in urban centers, heavier footprint in remote sites like Huntsville’s G8. They also unfortunately highlighted issues like civil liberties concerns – the Toronto G20 saw mass arrests and some criticism of overly aggressive security (though interestingly, much criticism fell on police; the military’s role was less controversial partly due to its low visibility there). After 2010, a federal review generally concluded RCMP and partners acted reasonably, but also needed to improve how they manage large protests and integrate intelligence.

Come 2018, the Charlevoix G7 in Quebec was another test. Lessons from 2010 were applied: the operation had a name (Cadence) but scaled to the threat environment – about 2,200 CAF, considerably fewer than 2002, reflecting that global terror threat was different (ISIS was a concern, but no 9/11-level immediate threat, and no major protest movement like early 2000s anti-globalization peaked). The CAF in 2018 emphasized specialized support: high-tech surveillance (they even brought a counter-mortar radaras mentioned) and quick reaction forces, but left crowd control to police. It also quietly implemented new tools like cyber defense (by 2018, cybersecurity was a major theme; indeed, G7 leaders in 2018 launched a Rapid Response Mechanism for countering cyber threats to democracy). Domestically, the CAF’s role was seen as normal – no serious political pushback occurred to having thousands of troops involved, indicating that by now Canadians accepted the pattern of “CAF supports RCMP for big events,” so long as troops stay in support roles (which they did – no soldiers arresting protestors was a deliberate policy).

Now in 2025, Kananaskis again – almost coming full circle to 2002’s scenario but in a more mature framework. The security environment includes new challenges (drones, disinformation, pandemics lingering in memory) and old ones (terrorism, protests). The CAF and RCMP have a well-oiled concept: the Integrated Security Group (or Unit, terminology changed slightly but same idea) is basically institutionalized. The Government has formally designated G7 2025 as a “Major International Event” which triggers predetermined protocols. We saw that in the funding brief to Parliament, referencing past summits and how ISSG will handle it. So there is continuity and expectation: everyone knows their lane better now.

One notable shift is domestic readiness as a core mission for the CAF. Canada’s 2017 defence policy “Strong, Secure, Engaged” explicitly prioritized being “Strong at home” – meaning the Forces must be ready to deploy in Canada for various crises. Mostly that refers to disaster relief, but also “major events” are mentioned. The CAF even created standing Regional Joint Task Forces (like JTF West, Pacific, East, etc.) to always have a command structure for domestic ops. This pre-structure likely made planning for G7 smoother: e.g., the commander of Joint Task Force West (based in Edmonton) could naturally take lead on the military side, rather than inventing an ad-hoc HQ. In 2002, they sort of had to create a JTF on the fly for G8; now it’s part of the playbook.

Another trend: civil-military coordination has become more transparent in process if not detail. For instance, the RCMP has publicly mentioned working with CAF and others early on, and we see joint press releases warning of convoys. Compare that to 2002, where a lot was secret until after (understandably then). This suggests confidence and normalization – they don’t hide that the army is out there; they announce it to avoid panic when folks see vehicles. However, transparency has limits: they still won’t say how many or what kind of vehicles, to keep adversaries guessing.

That’s why F-18s making noise or LAVs on highways serve a purpose beyond their technical role. It’s a form of security theater (not in the sense of useless show, but in the literal sense of a visible demonstration of capability to shape perceptions). On the other hand, much is kept opaque – Canadians don’t get to know the exact sniper positions or the criteria for a fighter to shoot, nor would revealing that help (quite the opposite). The line between public accountability and security secrecy is carefully walked.

Canadian authorities tend to err on the side of secrecy during the event (for safety), then modest transparency after (through some stats or lessons learned releases). For example, DND archived a public page after 2018 summarizing numbers, and one might expect a similar summary post-2025 (like “CAF deployed X personnel, Y vehicles, flew Z hours, etc.”). During, they clam up. This can frustrate media – but usually media in Canada understand, and instead they go to “experts” (often retired officers or academics) to get estimates, much like we have done in this brief.

Civil Liberties and Perception: The presence of the military in domestic operations always raises the question of how far is too far in a democracy. Canada generally has acceptance when it’s clearly in support of civilian lead and temporary. If soldiers were, say, directly confronting protestors, that would be a red line likely causing outcry. The integrated model purpotedly avoids that: police handle protesters; military is a backdrop for scenarios beyond protest (terror, etc.). This supposed segregation of duties reflects lessons from events like the 1970 FLQ Crisis (War Measures Act deployment in Quebec) which left a lasting cautious attitude about using troops domestically but is largely an artificial siloiung. In modern times, by keeping the CAF role niche and technically focused, they avoid the optics of “troops policing Canadians.” And indeed, as noted earlier, CAF members are not officially doing law enforcement, a point they dishonestly highlight to this day.

Information Warfare and Narrative: Interestingly, one new aspect in 2025 is the information space – disinformation or foreign influence attempts around the summit. G7 summits attract hackers and trolls (recall in 2018 G7, there was a nasty falling-out with a certain U.S. president tweeting about our PM afterwards – the narrative can overshadow the event). Canada and partners have a “Rapid Response Mechanism” for defending democracy (which started at G7 2018). So you can bet part of the security is also monitoring social media for false alarms or propaganda that could incite panic or confusion. This is more in CSIS/CSE domain, but the CAF could lend open-source intelligence analysts or use its influence activities expertise to help counter any psy-ops. That’s a far cry from the boots and barricades of physical security, but it’s now part of comprehensive security.

Costs and Criticisms: The cost of these operations is huge – 2002 reportedly cost over $200 million (the Italian G8 2001 cost ~$225M and Canada’s was expected double that, possibly due to remote logistics). 2010 G8/G20 cost even more (around $1 billion for both events combined, security-wise, a domestic political issue at the time). 2018’s G7 was in the hundreds of millions. The 2025 one will also be expensive. Some critics argue these could be scaled back or that having so many summits is not worth the trouble. Proponents say it’s the price of global leadership and that you can’t put a price on safety of world leaders. OSINT doesn’t give us the full ledger, but glimpses like the RCMP needing an extra $45 million just to start planning is telling. The CAF absorbs a lot of the cost in their regular budget (or gets reimbursed by summits budget after). Regardless, one can anticipate the usual post-event debate: did we need to spend X on security, given nothing happened? It’s a Catch-22 – if nothing happens, some feel it was overkill; if something did happen, the narrative would be “not enough done.”

From an intelligence perspective, one can appreciate that deterrence is partly achieved by overmatch – having so much security that anyone with malintent is discouraged. The “theater” aspect is part of deterrence: e.g., if a hostile sees ADATS missiles and constant jets (like in 2002), they think twice. If they see heavy cyber monitoring, they might not bother hacking, etc. In 2025, an adversary might consider a small drone attack – but knowing Canada’s deploying new anti-drone tech (implicitly signaled by how they emphasize CBRNE and EW contributions) might dissuade them. It’s like showing your hand partially to scare them off, while keeping enough hidden that if they do try, you catch them.

Civil-Military Coordination: Over the years, the trust and rapport between RCMP and CAF has grown. In 2002, personalities like BGen Fenton (CAF) and C/Supt Hickman (RCMP) built an effective working relationship that was credited for success. Now, coordination is more structural. ISSG is the vehicle, and likely many officers involved have done this before (perhaps in 2010 or 2018). Knowledge transfer is key. For example, Maj-Gen (later Lt-Gen) Chris Coates was a NORAD officer during 2010 Olympics who helped integrate air defense; those lessons were passed on and updated for G7s. As OSINT researchers, we can sometimes identify recurring names in planning conferences or exercises held in advance (the CAF and RCMP often run a series of joint exercises, like Exercise MAGNITUDE was done before 2010 Olympics to test the security concept). If any such exercise happened for 2025, it might have been mentioned obscurely in DND press releases.

In conclusion, the Canadian approach to summit security has shifted from ad hoc and heavily secretive (2002) to more standardized and confidently integrated (2025) in which the secrecy and potential; for abuse is presented as reduced but remains as it always has been. Yet, each event tailors the scale: 2025’s response might not be as over-the-top as 2002’s perhaps, but more than 2018’s likely, because Kananaskis’s terrain demands more boots and tech. The CAF’s increasing involvement in domestic tasks (fires, floods, pandemics, and summits) shows a force adapting to broad roles. Some call this the “constabulary” or “whole-of-nation” role for modern militaries – not just war-fighting but backing up civil authorities regularly.

For the general public, the takeaway is that such operations are both reassuring and faintly disquieting: reassuring that all possible measures are taken to prevent harm; disquieting that such measures are necessary and that our scenic wilderness becomes a fortified zone for a few weeks. The ideal outcome, as always, is nothing dramatic happens. If the summit concludes uneventfully, security will declare success and pack up by June 18th. Most military units will be back in their barracks by end of June, perhaps a bit tired but proud that their large-scale rehearsal of readiness remained just that – a rehearsal, not a real emergency.

And we, as open-source observers, will have witnessed a complex ballet of defense unfold in real time, largely through indirect clues. It’s a reminder that in an open society, even secret efforts cast a shadow visible to those who pay attention. This brief itself is evidence: using only public information and history, we painted a comprehensive picture of something inherently meant to be low-profile. That speaks to the power of OSINT – and also to the Canadian ethos of conducting security operations in a manner that can withstand public scrutiny, even if details emerge later.

Final Thoughts: Under the banner of Prime Rogue, we have analyzed the Canadian Armed Forces deployment for the G7 with a critical but appreciative eye. It’s equal parts strategy and spectacle, caution and capability. As the summit commences, the world’s attention will be on the leaders and their agendas; but we’ve shone light on the vast apparatus working behind the scenes to keep those leaders safe. It is a fusion of high-tech surveillance and age-old logistics, of stealth and showmanship. And it underscores a truth of modern international diplomacy: when the world’s powers meet in a tranquil spot, they bring a small army with them – not to project power abroad, but to guarantee peace and security at home, and intimidate the domestic population.

Sources for all factual claims in this brief are derived from open publications, official statements, and historical records, cited throughout. This analysis used no classified or privileged information. The picture we assembled is, by necessity, an informed approximation – the true operation will have nuances only known to insiders. But as the saying goes, “forewarned is forearmed,” and we trust this brief leaves our readers well-forewarned about what to expect (and what is expected of the security forces) when the 2025 G7 comes to Kananaskis.

Have a safe summit, and happy observing.

If you missed Part 1 of the Prime Rogue Inc G7 2025 series, “RCMP Security mOperations for the 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis – 2025 G7 Security Series #1,” you can check it out here.

[…] QEII) are publicly viewable; set them for realtime or time-lapse. Media reports already note that CAF military vehicles are moving between Edmonton and Calgary (May 15–30) ahead of G7. Use these cues: convoys will likely use major routes (Anthony […]

[…] notably “CAF members did not conduct law enforcement” – they acted in support of the RCMP. We see the same structure for 2025: the CAF’s Western Area has already been moving convoys of mili…, and a new Integrated Security Unit (ISSG) was formed. The ISSG includes RCMP, Canadian Armed […]

[…] evaluated the risk of chemical, biological, and radiological attack in their threat assessments. In Kananaskis 2025, Canada’s military and RCMP will have CBRN detection units and hazardous materi… The UK delegation is likely bringing along CBRN expertise as well – for instance, specialist […]

[…] BKA agents will be stationed on the Chancellor’s floor and at his door, working with RCMP and Canadian Special Forces assigned to G7 venue security. They employ countersurveillance and protective intelligence tactics – e.g. scanning for unusual […]

[…] and Drills with Host Nation SOF: Coordination with Canadian authorities for GIS is crucial since they are effectively foreign militar… There may also be joint familiarization exercises: GIS could quietly participate in tabletop […]

[…] Red Flag (High Risk – Security): The sudden Israel–Iran military confrontation has sharply elevated global terror alert levels just 48 hours before the G7. Canada’s security establishment is reacting with an unprecedented lockdown of the Kananaskis summit zone and surge deployments of military and intelligence assets. A 13-mile secure perimeter around the remote mountain venue is effectively turning Kananaskis into a fortress. NORAD air defenses are at peak readiness, enforcing a 30-nautical-mile no-fly zone over the area. Sp… […]

[…] NORAD, established in 1957, is a binational command integrating Canadian and U.S. air defence. Its rules of engagement allow cross‑border operations. Typically, Canadian CF‑18s intercept threats inside Canada while U.S. fighters defend Alaska and the continental U.S., but each side can support the other. The use of a U.S. KC‑135T and F‑15s over Calgary highlights this cooperation. During large events, such as the 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis, U.S. fighters provided air cover while CF‑18s enforced restrict…. […]