Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

The 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis, Alberta will see an extensive U.S. security and intelligence presence supporting President Joe Trump. This briefing analyzes the likely deployment footprint, special assets, and protocols in place, based entirely on publicly available information. It covers the U.S. Secret Service’s protective operations, involvement of elite military units, air mobility and overwatch plans, advanced protective technology, jurisdictional considerations for U.S. agencies in Canada, historical summit security precedents, and current open-source indicators of pre-positioning. All assessments are grounded in OSINT sources and prior summit patterns, avoiding any sensitive or non-public details.

Check Out Prime Rogue Inc’s Adversarial OSINT Guide for the 2025 G7.

The U.S. Secret Service (USSS) will have begun preparations well in advance of the June 15–17 summit. Typically, an advance team of agents arrives weeks ahead to work with host-country security and map out every detail of the President’s movements. They liaise closely with the RCMP’s Protective Operations unit (which protects visiting VIPs in Canada) to integrate plans. Early in the process, USSS invites local and federal partners to planning meetings. Past examples show the Secret Service coordinating with local tactical units for tasks like counter-sniper placement rather than acting unilaterally. We can expect a joint USSS-RCMP security task force (often called an Integrated Security Unit) to be in place, as was the case in 2018 when the RCMP led an Integrated Security Unit of police/military for the Charlevoix G7.

President Trump’s core protective detail will deploy in strength. This includes the Presidential Protective Division agents and the specialized Counter Assault Team (CAT) – tactical agents armed with heavy weapons to repel any attack on the motorcade or venue. The CAT usually rides in black SUVs (code-named “Hawkeye Renegade”) with running boards, enabling agents to ride outside ready to engage threats. USSS Counter-Sniper teams will also be in place on high vantage points. These snipers, often armed with high-precision rifles, operate in coordination with Canadian sniper/ERT units to maintain overwatch of all sensitive areas. During the 2010 G20 in Toronto, for instance, sniper teams were deployed on rooftops throughout downtown – a pattern likely repeated in Kananaskis (with mountain terrain offering natural high-ground for overwatch).

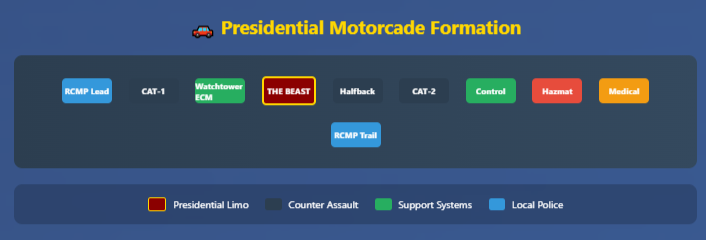

The Presidential motorcade in Alberta will be a substantial convoy, despite the remote location. It is typically composed of dozens of vehicles performing dedicated roles. The centerpiece is “The Beast” – the armored presidential limousine – likely accompanied by an identical decoy limo. These travel in the middle of the motorcade, flanked by protective SUVs. Immediately trailing the President’s car is an SUV carrying the close-protection agents (code-named “Halfback”) with at least one agent visible and armed, providing a first line of defense. Also embedded are an Electronic Countermeasures vehicle (code name “Watchtower”) sporting radio-frequency jamming antennas to thwart remote-detonated bombs and even to detect or jam hostile drones. A Control/Support vehicle carries the military aide and communications staff – including the bearer of the “nuclear football” – ensuring command and control continuity. One or more CAT SUVs (“Hawkeye”) with heavily armed tactical agents provide a quick reaction force. An Intelligence/coordination vehicle in the convoy will link with surveillance teams and local police to relay threat updates in real time. Bringing up the rear, crucially, is a Hazardous Materials Mitigation unit (a technical truck with sensors for chemical, biological, or radiological threats) and an ambulance staffed with paramedics. Local Canadian police cruisers lead and trail the convoy as well, handling route clearing and traffic control. The motorcade’s exact layout is kept discreet, but past VIP visits (e.g. Biden’s 2023 Belfast visit) showcased these elements arriving by air in advance.

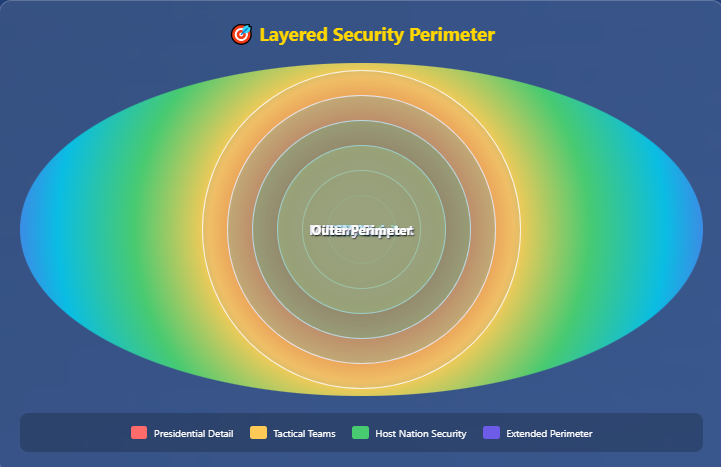

At the summit site (the Kananaskis Resort area), the USSS will establish a security bubble around the President. Per protocol, the RCMP is the lead agency on Canadian soil for overall summit security, and RCMP’s VIP Protection Detail will work side-by-side with the USSS. The President’s immediate protection stays with USSS agents, but RCMP officers provide an outer layer and handle jurisdictional matters. An RCMP Incident Command Post will be in operation (as noted in Nav Canada planning documents) to authorize flights and coordinate law enforcement. Expect joint RCMP-USSS tactical deployments: e.g. mixed teams securing rooftop and perimeter positions, and RCMP Emergency Response Team (ERT) members paired with U.S. agents for quick response. During the Charlevoix G7 (2018), RCMP had a massive presence (~5,000+ personnel) and coordinated closely with foreign protective details. Similar if not greater cooperation will occur in Kananaskis. Notably, Kananaskis’ remote “one way in, one way out” geography is a security advantage, but it requires intensive planning for motorcade route security (Highway 40 from Calgary) – likely lined with RCMP highway checkpoints and QRF teams. Alberta RCMP and local Calgary Police would have scouted and secured every potential choke point. By summit week, the RCMP Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG) will enforce road closures and trail shutdowns in the area. We assess that the U.S. advance team arrived several weeks early to run motorcade route drills and to set up command posts, working from the U.S. Consulate in Calgary and in Kananaskis itself under RCMP escort.

Behind the scenes, elements of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) are very likely involved in President Trump’s security for the G7 – a practice with established precedents. Tier-1 special mission units such as the Army’s Delta Force (Combat Applications Group) or Navy DEVGRU (SEAL Team Six) often deploy discretely as an added counter-terrorism layer when the President travels abroad. These personnel operate under diplomatic cover (e.g. as “military advisers” or embedded within the Secret Service detail) since foreign law prohibits foreign military operations on Canadian soil. Their role is contingency-based: to respond to extreme scenarios like a hostage crisis or complex terror attack that local forces and the Secret Service alone might struggle to counter. Open-source info confirms that “Delta Force, along with its naval counterpart DEVGRU, also protect the President when he is in countries […] where the Secret Service’s capabilities are limited.” While Canada is not a conflict zone, the high profile of G7 and the potential for sophisticated threats (e.g. terror groups, drones, or WMD scenarios) means a small JSOC contingent is prudent.

During the 2010 G20 Summit in Toronto, U.S. special operators were reportedly on scene. In that event, American Navy SEALs surreptitiously patrolled the harbour to guard against waterborne threats, and a U.S. Marine helicopter was observed hovering over downtown. This indicates Tier-1 or equivalent units were covertly integrated into security efforts, likely with Canada’s consent. At the 2018 Charlevoix G7 in Quebec, details were less public, but by analogy the U.S. probably deployed a small Delta/DEVGRU team on standby. (Notably, Japan’s Special Forces Group was on alert during the 2016 G7 in Ise-Shima, and German GSG-9/KSK units secured Elmau G7 2015 – highlighting that host nations expect and tolerate elite CT units at summits.) More openly, a recent incident confirmed Delta’s role: In October 2023, President Biden’s visit to Israel (an active war zone at the time) saw Delta Force operators in his entourage, acknowledged when an official photo accidentally revealed their presence. In that case they were tasked with hostage-rescue support; for a G7 in friendly territory their mission would be standing by for any terrorist or near-peer threat.

Under Canadian law, foreign armed personnel have no authority to act unless an arrangement is made. Likely, any U.S. special forces in Kananaskis would be unarmed or discreetly armed and poised to act only in extremis, and possibly stationed on U.S. assets (like an aircraft or the grounds of the U.S. consulate team’s quarters) to maintain a form of U.S. jurisdiction. Any deployment would be done with tacit approval via diplomatic channels. (For example, during President Bush’s 2004 visit to Ottawa, Canadian media noted heavily armed “U.S. security teams” had limited freedoms, operating under the watch of RCMP.) At Kananaskis, a reasonable conjecture is that a small Delta Force detachment (probably fewer than 20 operators) will rotate through Calgary. They might train with Canadian JTF2 or RCMP ERT in the days prior (to familiarize with the terrain and deconflict roles), but remain in the shadows unless a crisis unfolds.

If an incident like a hostage-taking or complex assault occurred, these Tier-1 operators could be called on with Canadian government approval to execute a rescue or neutralization, in support of (or in coordination with) Canadian responders. Until then, their presence will remain virtually invisible – for example, some may blend into the CAT vehicles or augment sniper teams with specialized gear (all without public acknowledgment). In summary, based on past summit security and current threat considerations, “JSOC’s finest” are almost certainly part of the protective umbrella for President Trump, acting as an emergency “force of last resort” within strict legal confines.

President Trump will arrive in Canada aboard Air Force One, landing at Calgary International Airport (CYYC). From there, given Kananaskis’s remote location, aerial transport is favored. The U.S. will deploy its Marine One helicopter assets to shuttle the President to the summit venue. In recent summits, the Marine One fleet includes VH-3D “Sea King” helicopters or the newer VH-60N/VH-92 models operated by Marine Helicopter Squadron One (HMX-1). These green-and-white helicopters are airlifted to the host country ahead of time. In fact, heavy U.S. Air Force cargo planes (C-17 Globemaster IIIs) have already been observed delivering the presidential helicopters and support equipment. For example, during the 2021 G7 in Cornwall, UK, plane-spotters saw USAF C-17s unloading a VH-3D Marine One at the local airbase. We anticipate a similar pattern in Alberta. Multiple C-17 flights will ferry the President’s armored limousines, SUVs, and helicopters into Calgary in early June.

Accompanying Marine One will be a contingent of MV-22 Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft and possibly CH-53 or MH-47 support helicopters. The MV-22 Ospreys, also operated by HMX-1 in presidential support, serve to carry additional staff, Secret Service agents, and supplies on the same flight routes as Marine One. They have become a common sight on overseas trips – for instance, Ospreys were seen flying over Cornwall in 2021 to flank Marine One’s operations. We expect two or three Ospreys in Marine One’s formation in Alberta, providing overwatch and rapid transport of the President’s team between Calgary and the secured heliport at Kananaskis. These aircraft significantly extend the range and capabilities of the motorcade – effectively bypassing ground threats by moving the VIP exclusively by air between major points.

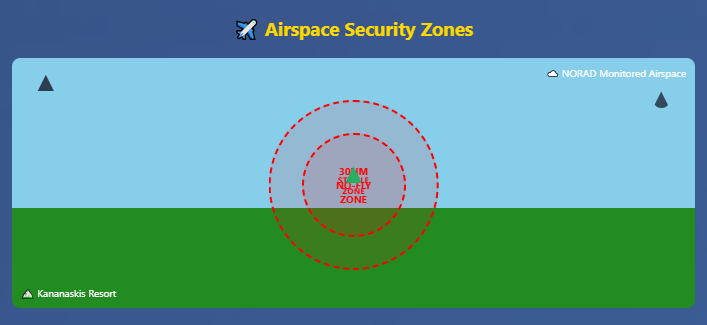

The summit will see strict airspace restrictions enforced by NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command) in partnership with Nav Canada. An Aeronautical Information Circular outlines temporary restricted airspace from June 10–17 in the Kananaskis and Calgary regions Two large Class F Restricted zones (30NM radius over Kananaskis heliport and 20NM around Calgary Airport) will be active, with graduated altitude and traffic limits. All non-authorized aircraft – including drones (RPAS) – are banned, and any violators “will be subject to intercept by armed military aircraft” with lethal force authorized if necessary. In effect, a no-fly zone will blanket the summit. The Royal Canadian Air Force, as part of NORAD, will station fighter jets on combat air patrol. Likely CF-18 Hornets will be airborne or on high alert at nearby bases, ready to scramble. These jets would intercept any suspicious aircraft well outside the summit perimeter.

Additionally, NORAD may utilize airborne early warning and control: an AWACS plane (E-3 Sentry) or Canadian radar assets to monitor the air picture. In 2018 Charlevoix, Canada even deployed a long-range radar and relied on NORAD coordination for summit air defense. For Kananaskis 2025, one of Canada’s forward radar sites in Alberta is integrated into this plan, and a dedicated military control zone (8NM radius) will exist directly over the resort for the summit’s duration. That zone will be managed by the Canadian Forces to deconflict any necessary air movements (such as military helicopters) and to respond instantly to incursions.

Both Canadian and U.S. aircraft will provide overhead surveillance. At Charlevoix 2018, the RCMP flew Pilatus surveillance planes in long orbits (one RCMP Pilatus PC-12 logged 17+ hours during the summit) to monitor ground activity. Similar surveillance aircraft or helicopters may patrol over Kananaskis – likely RCMP or Canadian military assets equipped with electro-optical sensors to watch for suspicious movements in the vast forests. The U.S. could supplement this with technical overwatch: for instance, a U.S. Army RC-12X Guardrail or an FBI aerial surveillance platform might covertly fly above, collecting signals intelligence or high-resolution video for protective intel. This would be done in coordination with Canadian authorities. We saw hints of such cooperation in Toronto 2010, where the NSA provided SIGINT support to summit security (as later leaked) and aviation units patrolled invisibly. At minimum, the U.S. Secret Service will tie into the Canadians’ air surveillance feeds – a Vice investigation from 2018 noted that while a hobbyist could track many planes at G7, Marine One and its escorts did not appear on ADS-B trackers for security. This indicates both U.S. and Canadian military aircraft go dark while patrolling the summit, using encrypted communications to coordinate out of public view.

In the weeks leading up to the summit, OSINT is already picking up unusual airlift activity into Calgary. Plane spotters have reported USAF cargo flights and air refuelers in the region. For example, multiple C-17s from U.S. bases are expected to land at Calgary carrying the presidential motorcade vehicles and equipment (historically a single visit can require 20 or more C-17 loads). The airbridge also includes KC-135 or KC-46 tankers to support Air Force One and fighter patrols in transit. While exact flight paths are classified, the FAA will publish VIP temporary flight restrictions (TFRs) for President Trump’s travel dates. We anticipate a TFR along the route from Washington D.C. to Calgary, and Nav Canada’s notices already foreshadow the summit’s airspace lockdown. On the ground, spotting enthusiasts might see the tail flashes of Air Mobility Command jets at Calgary’s airport and possibly at Edmonton (where Canadian forces are staging equipment as well). The Marine One helicopters and Ospreys will likely conduct test flights around Calgary (similar to what was observed at RNAS Culdrose in the UK when the helicopters were test-flown after delivery). These flights, though not publicly advertised, can sometimes be glimpsed by local media or residents due to the distinctive sound of Ospreys.

In summary, air mobility is a critical piece of the U.S. security plan: it reduces the President’s exposure on long road movements and provides a rapid evacuation option if needed. Overhead, a layered air defense and surveillance posture – from fighters and radar to no-fly zones – will guard the summit from aerial threats, fully integrated between U.S. and Canadian forces.

Modern protective operations at a high-profile summit involve an array of specialized technology to counter emerging threats. The U.S. team in Kananaskis will bring advanced gear to detect, deter, and defeat hazards ranging from drones to WMD materials, working in concert with Canadian systems.

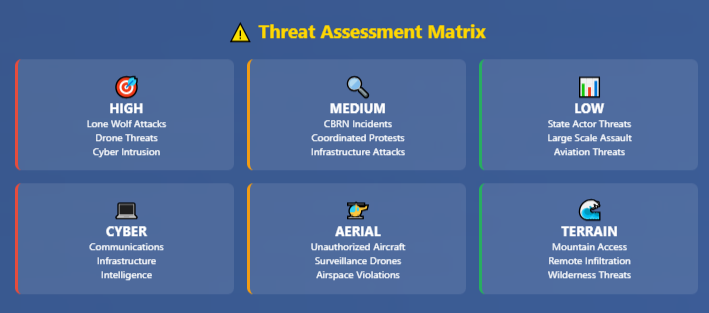

The threat of unauthorized drones – for spying or attack – is a top concern. Canada has dealt with this in past summits by deploying electronic countermeasures and even kinetic intercept tools. During the 2018 Charlevoix G7, the Canadian Forces and RCMP implemented dedicated anti-drone restrictions (RCMP was given authority over Counter-UAS at the event). By 2022’s G7 in Germany, the security forces publicly used systems like SkyWall Auto Response, a vehicle-mounted net launcher that can track and physically capture rogue drones. SkyWall handheld units have been present at G7 events since 2017. We can expect similar or upgraded C-UAS tech in Kananaskis: possibly German-made GUARDION jamming systems (which were deployed in Elmau 2022), and U.S.-made systems like the DroneDefender or newer RF disruptors that the Secret Service has tested. The U.S. Secret Service likely fields its own portable drone-detection sensors (RADAR or radio-frequency scanners) around the President’s vicinity. In the motorcade, as noted, one SUV carries short-range radar and can even deploy countermeasures against incoming UAVs. Additionally, the Canadian military has experience using radar such as the SRC Inc. AN/TPQ-49 to spot low-flying drones; indeed, that system was used to provide air surveillance during the Charlevoix summit. Thus, a combination of fixed surveillance radars, optical trackers, and mobile interceptors (net guns or jamming guns) will create a multilayered C-UAS umbrella over the summit. All unauthorized drone flights are explicitly banned starting June 10th under the restricted airspace rules – and any detected will face immediate intervention. The summit security command center will likely integrate U.S. and Canadian drone-tracking feeds so that a threat can be responded to by whichever team is best positioned (RCMP helicopters, USSS teams with drone guns, etc.).

On the ground, USSS and RCMP will deploy sophisticated surveillance equipment to pre-empt attacks. Expect thermal imaging scopes and long-range cameras mounted at observation posts to watch approaches to the resort day and night. The Secret Service’s Counter Sniper Team is trained to use thermal optics to spot hidden gunmen or suspicious movement at long distances. They also utilize the “Boomerang” gunshot detection system in some motorcades – a sensor that immediately pinpoints the origin of a gunshot. While specific equipment is classified, past summit security contracts have included acoustic sensors around venues. The protective teams may also use laser detection devices to warn of anyone targeting the VIPs with a sniper scope (which can reflect lasers) – akin to how the motorcade’s sensors can detect laser-ranging from missiles. Canadian ERT units similarly will have sniper/spotter pairs placed strategically; per protective doctrine, these sniper teams from both nations will have overlapping fields of view covering all high-risk sectors like building rooftops, hillsides, and crowd areas.

Summit security must also mitigate any WMD threat, however remote. The U.S. is expected to field specialized units for this purpose. The Secret Service’s Hazardous Materials Mitigation Unit (one travels in the motorcade) carries detection gear for radiological, chemical, or biological agents. Agents from the USSS Technical Security Division will deploy handheld sniffers that can detect chemical warfare agents or toxic gases in event sites. It’s common for the Secret Service to pre-screen all venues with chemical agent detectors (such as mobile mass spectrometers or ion scanners) and to monitor air quality in realtime around the President. On the radiological front, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Radiological Assistance Program (RAP) likely has a small presence. RAP teams provide radiation detection equipment and expertise; while they don’t preempt local authority, they can advise and lend advanced gear. The DOE and FBI routinely secure major events in the U.S. (like inaugurations) with the Nuclear Emergency Support Team (NEST) – including mobile radiation detection units and even helicopter-mounted radiation sensors. For a foreign event, Canada will lead CBRN defense (the Canadian military has specialized CBRN teams on standby under Operation Cadence in 2018, for example), but the U.S. probably inserts some scientific liaison from FBI or DOE to quietly sweep the areas where the President will be.

If any suspicious substance or device is found, FBI specialists from the Hazardous Materials Response Unit (HMRU) may be part of the President’s traveling party to assist. It’s known that NEST supported events like the 2004 Athens Olympics abroad, under diplomatic arrangements, so similar support is plausible here. The medical unit accompanying the President (White House Medical Unit) also adds a layer of bio-defense – carrying antidotes and medical countermeasures for chemical or biological attacks, and coordinating with Canadian hospitals for emergency response.

An often overlooked aspect is securing communications and protecting against cyber intrusions. The Secret Service and White House Communications Agency (WHCA) will establish secure comms at the summit – encrypted radios, SATCOM links, and hardened phone lines. While not visible, they will work with Canadian signals intelligence to detect any unusual RF activity (like an RC IED trigger signal or drone control link). The electronic warfare teams in the motorcade (like the Watchtower ECM vehicle) jam hostile frequencies, but at the venue, there may also be stationary jammers to protect key meeting areas from remote-triggered bombs. All wireless devices near the President will be closely monitored or filtered. Given the digital threat environment, U.S. Cyber Command or NSA personnel could be attached in a defensive role – hunting for signs of hacking or communications interference targeting the summit or Air Force One. Canada’s CSE (Communications Security Establishment) certainly will be doing the same, and it’s likely there is joint intel sharing. (Indeed, documents revealed the NSA heavily monitored communications during Toronto’s G20 – indicating a robust SIGINT presence).

In sum, the protective technology deployed is multi-faceted: electronic jamming, advanced sensors (optical, RF, chemical), and hardened communications all form a shield around the President. This technology, combined with highly trained personnel, is aimed at early threat detection and rapid neutralization. Publicly, officials will not detail these measures, but the summit’s $600+ million security price tag (for Charlevoix 2018 and similarly high for 2025) reflects these investments in cutting-edge protection.

One question is to what extent U.S. Department of Homeland Security agencies like the Federal Protective Service (FPS) operate in Canada during the summit. The short answer: their role is minimal and mostly limited to advisory or liaison functions, due to jurisdictional limits. The Federal Protective Service is charged with protecting U.S. federal buildings domestically. In Canada, FPS has no authority to police or guard facilities outside U.S. diplomatic missions. There is a U.S. Consulate in Calgary, but its security falls to the State Department’s Diplomatic Security Service (DSS) and host-nation law enforcement – not FPS. It’s unlikely FPS officers would deploy to Canada at all, except perhaps a small detail to inspect any temporary U.S. government-operated facilities at the summit (for example, if the U.S. delegation sets up an office at a venue, FPS might advise on physical security standards). More likely, any building security needs are handled by Diplomatic Security and the Marines. U.S. Marine Security Guards will be reinforced at the U.S. Embassy in Ottawa and possibly a temporary detail at a “USA” summit office or the hotel housing the U.S. delegation in Calgary.

However, DHS does have a presence in broader summit security in terms of expertise. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) will be involved in screening the influx of international visitors at airports and land crossings, coordinating with CBSA (Canadian Border Services Agency) to flag any persons of concern heading to protests or otherwise. The U.S. Secret Service itself is now under DHS, and they often bring in other DHS sub-agencies for support. For instance, DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) could quietly assist Canada in protecting critical infrastructure (power grids, communications) around the summit from cyber threats – though this would be advisory. The TSA might station inspectors at Canadian departure airports for Air Force One and military flights as an extra layer of screening, but again under host nation invitation.

Legally, any U.S. federal agents in Canada (outside of the diplomatic protection function) require authorization. There exists a standard protocol for foreign law enforcement in Canada, usually handled via Global Affairs Canada and the RCMP. For this summit, Canada likely issued blanket accreditation for the Secret Service agents and certain others (like FBI or DOE specialists) as part of the U.S. delegation. But those agents do not have free rein; they carry firearms only by Canadian permission and are typically shadowed by RCMP liaison officers. The Federal Protective Service does not have a natural role fitting that description, since they protect U.S. facilities. One could imagine a scenario where FPS personnel help secure the “USA House” – the delegation’s working offices – but that would still be under DSS lead. In practice, the U.S. would lean on the host country for facility security. For example, if the U.S. delegation has a secure conference room or sensitive equipment at the summit media center, the RCMP and Canadian Forces will guard the perimeter, while U.S. personnel secure the inside.

It’s worth noting DHS has deployed personnel abroad for major events when requested – e.g. Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) agents often assist foreign counterparts on border security around events, and FPS has sent observers to learn from foreign large-event security. But operational constraints in Canada mean U.S. officers cannot exercise police powers. Therefore, any DHS assets present (beyond Secret Service) are in advisory or analytical roles. For instance, the DHS Office of Intelligence & Analysis might have analysts embedded in the intelligence fusion center for the summit, working alongside Canadian intelligence to share threat info (particularly on any cross-border extremist threats or persons of interest traveling from the U.S. to Canada).

In summary, no overt FPS deployment is expected in Canada for G7. The protective mission rests with Secret Service and State Department security for U.S. officials, and the RCMP for everything else. DHS will contribute through its component that matter most – the Secret Service – and through behind-the-scenes intelligence and technical support, rather than any visible policing presence on Canadian streets.

Security operations at past G7/G8 summits provide context for what is unfolding in Kananaskis. Key lessons and patterns from Biarritz 2019, Charlevoix 2018, Gleneagles 2005, and similar events are being applied:

In summary, historical patterns show a consistent escalation of security integration and technology, balanced by choosing remote venues to ease the burden. Kananaskis 2025 is essentially the culmination of these lessons: an isolated location locked down by a multi-layered force, employing cutting-edge surveillance and counter-threat measures, and coordinating international protective teams with precision. The U.S. contingent operates within this structure, adding its unique capabilities (like rapid airlift for the President and unmatched CT units) to Canada’s formidable base of operations.

With a week or so to go before the summit, open-source indicators of the security buildup are increasingly evident. Here are the key OSINT observations and what they imply:

In summary, current OSINT paints a picture of intensifying logistical and security activity in Alberta as the G7 summit nears. From heavy airlift flights delivering presidential assets, to convoys relocating military gear at night, to formal notices establishing no-fly zones and road checkpoints – all evidence points to a massive, coordinated security operation gearing up. These open-source pieces not only confirm the summit’s support structure but also allow us to gauge its scale: clearly, the U.S. is heavily invested in securing the President, working within an enormous Canadian-led security apparatus. By monitoring these indicators in the coming days (flight logs, NOTAM issuances, local reports), one can continue to track the evolution of the security posture right up to the summit’s start.

All available open-source information indicates that President Trump’s attendance at the 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis will be safeguarded by one of the most robust and comprehensive security operations ever deployed on Canadian soil. The U.S. is integrating its elite protective resources – from the Secret Service’s layered detail and cutting-edge countermeasures to the quiet backing of special operations forces – into the Canadian-led security framework. The Secret Service will maintain an immediate shield around the President with its agents, armored motorcade, and technical arsenal, closely meshed with RCMP units at every step. In the shadows, Tier-1 military operators stand ready as an emergency contingency, reflecting lessons learned from past crises. Overhead and along the mountain roads, a formidable array of air defense, surveillance platforms, and logistical support craft ensures control of the skies and rapid mobility for the Commander-in-Chief. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, technology to defeat drones and detect WMD threats adds invisible layers of protection.

The situation on the ground in Alberta – gleaned through OSINT – reveals a security operation already in motion: equipment is in place, airspace restrictions planned, and thousands of security personnel preparing for all scenarios. Historical patterns from previous summits reinforce why these extraordinary measures are in play: the risk profile of a G7, with world leaders concentrated in one venue, demands nothing less.

While much of the security activity will remain behind a curtain of secrecy, the open-source pieces allow us to assess with high confidence that the U.S. protective mission is deeply coordinated, well-resourced, and primed to respond to any threat during the summit. In effect, Kananaskis will be transformed into a fortified enclave – a “green zone” – for the G7’s duration, with U.S. security components working hand-in-glove with Canadian hosts. All signs indicate that President Trump’s safety will be secured through exhaustive preparation, interoperability with Canadian security, and the formidable presence of U.S. protective assets on land, air, and even in the electromagnetic spectrum – in spite of ongoing of American threats to Canadian sovereignty. This OSINT-driven analysis, pieced together from publicly available data and historical precedent, underscores the immense scale and sophistication of protection that accompanies the U.S. President to an event of this magnitude.

Editor’s Note: All of this information is sourced from the public domain and logical inference.