Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

There is a peculiar kind of magic in Canadian administrative law—the ability to appear procedurally fair while functionally deferring to power. Nowhere is this more evident than in the evolving jurisprudence of Section 6.1 of the Access to Information Act (ATIA), a discretionary power that allows institutions to request permission from the Office of the Information Commissioner (OIC) to refuse to process certain access requests. On paper, this is a narrow tool—reserved for requests that are vexatious, made in bad faith, or otherwise constitute an abuse of the right of access. In practice, however, Section 6.1 has become a bureaucratic kill switch: an invitation for federal institutions to outsource the act of denial to a Commissioner who increasingly appears more concerned with caseload management than safeguarding quasi-constitutional rights.

To be clear: the problem is not the existence of Section 6.1. The problem is how it’s being operationalized—through conclusory decisions, boilerplate reasoning, and a procedurally defensive posture that routinely invokes the Privacy Act as both shield and sword. In dozens of decisions, the Commissioner cites generalized concerns—”high volume,” “disruptive tone,” “overlapping scope”—as grounds for refusal, while refusing to disclose the underlying facts that would allow those conclusions to be meaningfully challenged. The rationale is always the same: the identities of requesters, their motivations, and the institutional details at play are protected under the Privacy Act, and thus cannot be fully revealed.

This is true, to a point. The Commissioner is bound by both the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act, and must ensure that personal information is not improperly disclosed in her decisions. But this compliance posture has become a convenient escape hatch—one that permits the OIC to construct opaque, seemingly neutral findings that are, in reality, deeply dependent on unshared facts, redacted assumptions, and deference to institutional claims. In effect, the OIC has transformed the Privacy Act from a shield for citizens into a smokescreen for itself. The result is a Kafkaesque regime where no one can know exactly why a request is refused, because acknowledging the facts that led to refusal would violate the privacy of the person being refused.

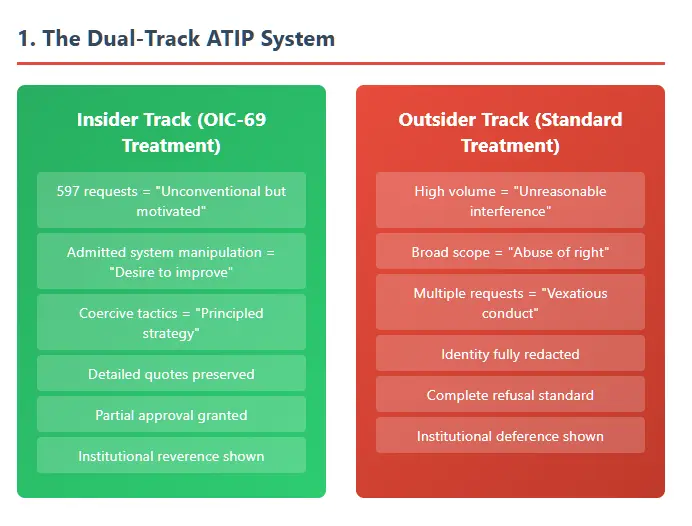

Nowhere is this more absurd than in the Commissioner’s flagship Section 6.1 decision—OIC-69. There, the OIC reviewed a batch of nearly 600 requests filed by a single individual, many of which targeted email inboxes of dozens of public servants, one two-month window at a time. What followed was not just a refusal, but a rare moment of administrative clarity: the Commissioner revealed that the requester had effectively attempted to blackmail the institution, offering to drop over 500 requests in exchange for faster responses on a smaller subset. The motive was laid bare—to inflate institutional delays, generate negative statistics, and apply pressure for more ATIP resources. The language of the OIC was damning, the facts clear, and the decision well-reasoned. But there was something else about OIC-69: a conspicuous gentleness, a sense that the requester was known, respected, and, unlike most, given the benefit of the doubt.

Who was this requester? The decision, of course, doesn’t say. It cannot say. But the pattern of facts, the sophistication of the strategy, and the institutional reverence with which the requester is treated—all point to a veteran access operator. There is strong circumstantial evidence that the requester is a highly prolific figure with institutional familiarity and a long track record in ATIP advocacy. And if this is the case, then OIC-69 represents something far worse than just a bad-faith requester gaming the system—it reveals a dual-track ATIP regime, one in which frequent players are indulged, even when engaging in coercive tactics, while ordinary citizens are stonewalled under the guise of resource protection.

This piece proceeds not as a neutral doctrinal analysis, but as a polemical indictment. It will argue that the Information Commissioner’s 6.1 decisions increasingly fail to meet the standard of reasonableness set by Vavilov, that their reliance on conclusory reasoning and evidentiary opacity undermines procedural fairness under Baker, and that the selective enforcement of standards—as seen in OIC-69—renders the entire regime structurally unsound. The law demands justification. The OIC offers vibes. And behind the bland language of public administration lies something far more dangerous: a sanctioned culture of denial dressed up as discretion.

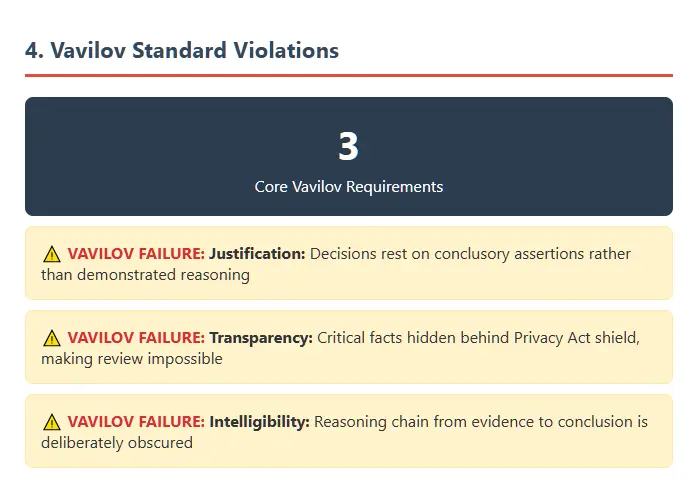

Administrative power in Canada does not operate in a vacuum. It is bounded—at least theoretically—by the principles of justification, intelligibility, and transparency. The Supreme Court’s decision in Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, was supposed to be the keystone of this architecture. In its crispest form, the standard articulated by the Court demands that administrative decisions must show how the facts, the law, and the reasoning connect. No amount of institutional deference can substitute for a coherent and evidence-based justification. The burden is on the decision-maker to demonstrate—clearly and on the record—why the outcome was lawful, reasonable, and fair.

On the surface, the Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada (OIC) pays lip service to Vavilov. Each Section 6.1 refusal decision includes boilerplate language referencing the legal threshold for “vexatiousness,” “bad faith,” or “abuse of the right of access,” as well as vague nods to discretionary considerations like public interest, operational burden, and duty to assist. But what Vavilov requires is not just recitation. It demands that the Commissioner connect the dots between the facts of the request, the institutional response, and the legal conclusion in a way that is both comprehensible and reviewable. Time and again, the OIC fails to do so.

Instead, the Commissioner deploys what can only be described as administrative sleight of hand. Broad conclusions are substituted for evidence; legal thresholds are satisfied by assertion; and concerns about operational disruption are elevated into de facto vetoes. The result is a growing body of decisions that perform the ritual of reasonableness while deliberately concealing the reasoning itself. Vavilov calls this out directly: “[r]easonableness is concerned mostly with the existence of justification, transparency and intelligibility within the decision-making process” (para 15). Where those elements are missing—where decisions rest on conclusory phrases, unshared evidence, or vague invocations of workload—the decision is not reasonable, no matter how many times the word appears.

Take for example the frequent refrain in Section 6.1 decisions that a request “would unreasonably interfere with the operations” of the institution. This is a legally recognized concern under the “abuse of right” doctrine. But in decision after decision, the Commissioner offers no empirical measurement of interference. No indication of staff allocation, resource constraints, budget lines, or mitigation strategies attempted. Instead, “unreasonable interference” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy—a conclusion declared rather than demonstrated. The OIC gives weight to an institution’s complaints about page counts or anticipated consultations, but rarely if ever interrogates how those numbers were generated, how they compare to institutional capacity, or whether they could be managed incrementally under the ATIA’s own time extension provisions.

Worse still is the growing reliance on institutional affidavits and representations that are not subject to adversarial testing. Under the current structure, the requester does not fully know that they are seeing all of what the institution submits to the Commissioner. Nor does the requester receive a full evidentiary package explaining why their request has been labeled abusive that is produced under any penalty of law. The result is a deeply asymmetrical process—one in which the institution can shape the narrative unchallenged, and the Commissioner, citing her obligations under the Privacy Act, can effectively refuse to disclose what the narrative even is.

This creates a direct conflict with the Vavilov model. The Supreme Court emphasized that “[w]here the reasoning that led to a decision is not apparent from the record, the decision cannot be found to be reasonable” (para 138). And yet, the OIC’s Section 6.1 decisions are often structured precisely to avoid revealing the reasoning. The Commissioner summarizes, paraphrases, and editorializes, but does not lay bare the evidentiary logic that would allow an external party—especially a judge—to determine whether the standard has been met. Key facts are omitted. Identities are obscured. Legal reasoning is compressed into single-paragraph conclusions. The result is not adjudication. It is a memo to file with the trappings of judgment.

Even more problematic is the extent to which this failure is systemic, not incidental. The OIC has developed a template structure for its 6.1 approvals: describe the request, outline the institution’s complaints, gesture toward attempted mitigation, and deliver a broad declaration of interference or vexatiousness. There is rarely a granular engagement with alternative remedies. There is no consistent application of public interest balancing. And in many cases, the Commissioner does not even attempt to reconstruct the actual purpose of the request, relying instead on assumptions about tone, timing, or volume.

In other words, the standard of reasonableness has been replaced with a standard of plausible deniability. As long as the decision appears to be structured, as long as the statutory language is recited, and as long as the institution’s version of events is summarized, the outcome is presumed valid. This is exactly what Vavilov warned against. It is also precisely what it sought to eradicate: the bureaucratic instinct to launder expedience through formality.

And herein lies the deeper institutional betrayal. The Information Commissioner is not a mere adjudicator. She is a constitutional actor charged with protecting the public’s right to information. Her role is to interrogate, not accommodate, the state’s desire to deny access. The Vavilov standard gives her the tools to do this. But rather than wield those tools as instruments of accountability, the OIC has used them as props—part of the performance of oversight that now functions primarily to shield the government from its own transparency laws.

The illusion of reasonableness, then, is more dangerous than mere unreasonableness. It creates the false impression of legality, the bureaucratic equivalent of a deepfake. And it is through this illusion that Section 6.1 has become something far more corrosive than originally intended: a quiet, unaccountable regime of refusal masquerading as administrative discipline.

In the Information Commissioner’s playbook, there is one phrase that appears almost religiously: “Due to privacy considerations, certain facts cannot be disclosed.” In decision after decision, the Commissioner explains—sometimes apologetically, sometimes not—that she is constrained by the Privacy Act from revealing the identity of the requester, the exact content of the request, the institution’s internal concerns, or any other contextual detail that might help an observer—or a court—understand what actually happened.

To the untrained eye, this appears prudent. A decision-maker must respect statutory privacy obligations, and the Commissioner, like any other officer of Parliament, is bound by the law. But to the trained eye—to the legally literate reader, or worse, the judicial one—this deference begins to look less like compliance and more like strategic concealment.

Let us be clear: the Privacy Act does restrict the disclosure of “personal information,” including names, identifying details, and content that could reasonably be expected to identify an individual. But it does not, and never has, required the OIC to render its decisions unintelligible. The Commissioner has wide latitude to anonymize, redact, or paraphrase. What she cannot do is invoke privacy to justify withholding the factual basis of her conclusions. And yet that is exactly what has become standard practice.

Consider the implications. A requester is accused of being vexatious, abusive, or acting in bad faith. They are barred from proceeding with their access request—potentially on matters of public consequence, or even legal significance—because of this finding. But they are never told the full reason why. The institution’s allegations are not disclosed in full. The Commissioner’s evidentiary analysis is redacted into abstraction. And when challenged, the response is the same: Privacy prohibits us from saying more.

This posture not only undermines procedural fairness, it immunizes the Commissioner’s decisions from meaningful review. The Vavilov standard requires that decisions be “transparent and intelligible,” particularly when they implicate fundamental rights. A requester seeking judicial review cannot test the reasonableness of the Commissioner’s conclusion if the critical facts have been placed behind a legal firewall. Nor can the court—tasked with reviewing the chain of analysis—trace how the evidence links to the outcome if that evidence is selectively paraphrased or concealed. In this way, privacy becomes the cloak for discretion, and discretion becomes the instrument of denial.

It is worth pausing here to note the asymmetry. The institutions submitting 6.1 applications have the full picture. They see the requester’s identity. They argue the case against them. They provide internal memos, workload charts, and—frequently—informal character assessments. But the requester sees none of this. Nor does the public. The Commissioner mediates these submissions in secret, filters them through a lens that cannot be verified, and then issues a decision that asserts conclusions without ever laying bare the basis for them. This is not administrative justice. It is gatekeeping by inference.

More troubling still is the fact that the Privacy Act is used selectively. When it suits the Commissioner to emphasize a requester’s history, motives, or frequency of filing, she will say so—albeit in vague terms. She will note that “the requester has made similar requests in the past,” or that “the tone of previous correspondence raised concerns.” She will allude to the fact that certain requests “appear to be part of a pattern,” or that they have been filed by “an individual with a long history of access activity.” These statements are, on their face, personal information. And yet they are invoked freely when they bolster the Commissioner’s decision to refuse.

But when those same details would expose inconsistency, bias, or questionable discretion—when, for instance, the identity of the requester might reveal that they are a well-connected frequent filer with political or institutional capital—the Privacy Act suddenly reasserts itself. The details are scrubbed. The facts are blurred. The decision is rendered in abstraction. This is not privacy protection. It is narrative control masquerading as legal duty.

This double standard reaches its most glaring expression in OIC-69.

There, for the first time, the Commissioner lays bare the nature of the requester’s conduct. Nearly 600 requests were filed. The motive, admitted by the requester, was to clog the system. The OIC quotes an email in which the requester states plainly: “I’m trying to grow the inventory. I want to push the backlog. I want them to feel the heat.” This is not a fishing expedition or a misguided information campaign—it is a calculated pressure tactic, bordering on institutional blackmail. And the Commissioner calls it out as such.

But here is the twist: unlike other decisions, where the OIC refuses to name or characterize the requester, OIC-69 is filled with implicit reverence. The requester is clearly known. Their motives are parsed with nuance. Their demands are described with striking candour. At one point, the Commissioner even justifies the requester’s conduct as being “rooted in a desire to improve access to information,” framing the mass request campaign as activism, not abuse.

If this had been any other requester—any journalist, researcher, citizen, or gadfly—the OIC would have invoked the Privacy Act to sanitize the entire affair. But not here. Not with this requester.

We will not speculate irresponsibly. But anyone familiar with Canada’s ATIP ecosystem knows there are very few individuals capable of generating hundreds of coordinated requests across multiple departments, with the language, leverage, and institutional memory required to use the system both procedurally and tactically. The OIC’s own deference to this requester—not just in tone, but in scope of disclosure—suggests institutional familiarity. This is someone on the inside of the access game, someone whose conduct, while condemned on paper, is treated in practice with preferential handling.

The irony is sharp. While average requesters are refused for “disruptive tone” or “volume,” here we have a requester who weaponized volume, leveraged delay statistics for policy impact, and attempted a coercive bargain—and yet received a multi-paragraph analysis affirming their legitimacy. The OIC even denies the institution’s 6.1 request in part, allowing the requester to proceed with a tailored subset. That’s a level of personalized accommodation unheard of in the rest of the 6.1 case law.

And still, the name is withheld. The facts are obscured. The Privacy Act is invoked—except when it isn’t.

In the hands of the Information Commissioner, the Privacy Act has become the bureaucratic equivalent of a one-way mirror. The institutions can see everything. The OIC sees more. The requester sees nothing. And the public sees what the Commissioner wants them to see—nothing more, and often much less.

This is not transparency. This is bureaucratic asymmetry weaponized by legal constraint, and it is wholly inconsistent with the Commissioner’s role as a guardian of the public’s right to know.

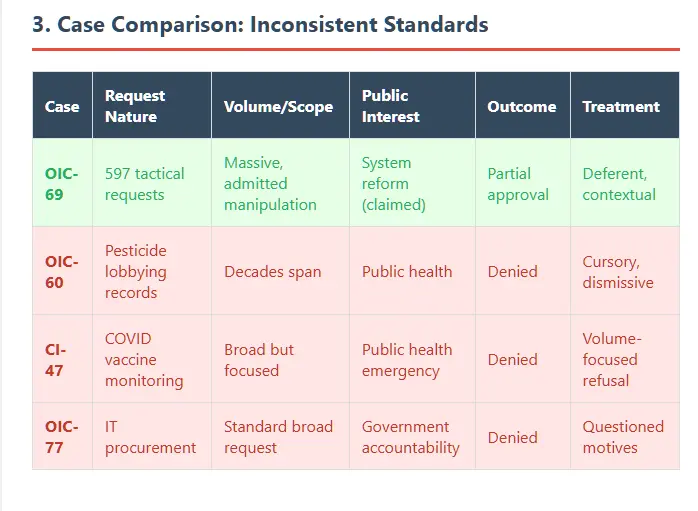

There is an old truth in bureaucracies: some people get processed, others get placated. In the case of OIC-69, the difference isn’t just visible—it’s glaring. This is a decision that, had it come from any ordinary requester, would have been a slam dunk for refusal under Section 6.1 of the Access to Information Act. Instead, it was treated with the kind of bureaucratic delicacy usually reserved for diplomats or, say, long-tenured access veterans with reputational equity inside Ottawa’s alphabet soup of agencies.

Let’s recap the facts—straight from the Commissioner’s own language:

Let’s not mince words: this is coercive behavior. It’s the weaponization of request volume not for the sake of accessing information, but to manipulate institutional optics. It’s not about transparency. It’s about leverage.

And yet—somehow—the tone of the Commissioner’s response is not outrage. Not alarm. Not even disapproval, really.

It’s admiration.

She notes that the requester’s strategy, while “unconventional,” was “motivated by a desire to improve the system.” She allows the abandonment of the 550 requests with little more than a sigh, while affirming the legitimacy of the remaining 47. She walks carefully around the conduct, acknowledges the pressure tactic for what it is, but ultimately concludes: This wasn’t abuse—it was ambition.

Interesting.

Because in every other 6.1 decision, the same ingredients—volume, disruption, opacity of purpose—are enough to warrant immediate refusal. In OIC-60, a single high-volume request about pesticide lobbying was dismissed as too burdensome, even though it pertained to matters of public health. In OIC-77, a broad IT procurement request was labeled abusive because the requester didn’t narrow the scope. In both cases, the tone was curt, the reasoning vague, and the decision leaned entirely on institutional affidavits. No quotes from the requester. No empathy. No parsing of intent.

But in OIC-69, the Commissioner quotes the requester directly. The tone is understanding. The conduct—indefensible in any other context—is contextualized. Even borderline extortionate behavior is reframed as noble activism.

And that invites a question.

Not who the requester is—we are of course not told, for Privacy Act reasons—but what they represent. Because there are, in truth, very few people in this country who:

Some might call them Canada’s foremost ATIP expert. Others might call them a perennial thorn. The OIC, it seems, calls them respected.

Let’s not speculate. Let’s simply observe that the treatment in OIC-69 is not only unique—it’s deferential. And not just deferential, but protective. The Commissioner’s decision doesn’t just describe what happened. It works—laboriously—to preserve the requester’s narrative legitimacy, to portray their scorched-earth filing campaign as a principled tactic. She never names them. But she makes sure we know they mean well.

You can almost see the institutional eye contact through the redactions.

Meanwhile, requesters with no name recognition—no “legacy” status in the ecosystem—are labeled disruptive for asking for too much, too loudly, or too often. Their motives are inferred negatively. Their tone is used against them. Their refusal to narrow a request is seen as obstinance; here, 550 abandoned requests is framed as collaboration.

We are not alleging collusion. We are pointing out a tone of familiarity. One that suggests the requester is not merely “known” to the system, but known well. The kind of known that gets your emails quoted without malice. The kind of known that lets you overwhelm a department, admit it, and still be given the benefit of the doubt.

There’s a word for this. It’s not corruption. It’s not favoritism.

It’s tiered accountability.

And it undermines every other 6.1 decision that came before it. Because if you can weaponize the system and still get partial approval, what exactly is the threshold? And more importantly: who exactly sets it?

Because based on OIC-69, the answer doesn’t appear to be “the law.”

Every administrative regime lives or dies by its internal consistency. When a discretionary power like Section 6.1 is exercised, it must not only be reasonable—it must look reasonable when compared across time and cases. This is especially true in the domain of access to information, where requesters are not just participants but system watchdogs, and where asymmetries of power are baked into every interaction between citizen and state.

It’s in this light that OIC-69 becomes not just anomalous, but radioactive.

When the Commissioner bends over backwards to accommodate a requester who deliberately clogged the system for tactical effect—and then frames it as an act of access heroism—she doesn’t just undermine that single decision. She delegitimizes the entire corpus of Section 6.1 refusals. Because if 597 intentionally burdensome, coercively framed requests are not a bar to accessing government information, then what is?

And more to the point: what were the rest of us denied for?

Let’s consider the contrast.

In OIC-60, a researcher asked for pesticide industry influence records. The request spanned decades, yes—but there was clear public interest, potential for a phased release, and no evidence of strategic misconduct. The OIC said no.

In CI-47, someone asked for COVID vaccine adverse reaction monitoring documents—arguably one of the most consequential information domains in modern public health. The OIC said no, citing volume.

In OIC-77, the requester had pending litigation and filed a broad—but procedurally standard—request for procurement communications. The OIC suggested they weren’t genuinely interested in all the records and upheld refusal.

None of these requesters filed 600 access requests. None attempted quid pro quo deals. None told the government their goal was to break the system. And yet their conduct, somehow, crossed the line.

What message does this send?

That access to information isn’t just about the quality of your request—but about who you are when you make it. That if you are a frequent filer with a “legacy” of access advocacy, you will be indulged—even when you behave like a strategic saboteur. But if you are unknown, or difficult, or inconvenient, your request becomes suspect the moment it costs the system anything.

That’s not law. That’s not reasonableness. That’s a class system, administered through footnotes and discretion.

The rot spreads in subtle ways. Once OIC-69 is accepted as part of the Section 6.1 body of decisions, it becomes a silent precedent. Not in the formal legal sense, but in the bureaucratic one: it shifts the Overton window of what’s considered “reasonable” conduct. Institutions now know that if a requester is known to the OIC, they may be treated with greater leniency. That some disruptive tactics, if dressed in legacy, will be sanitized as advocacy. And conversely, that the threshold for bad faith or vexatiousness will be lowered for everyone else—especially those with no platform to push back.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. Institutions, having seen how the OIC responds to insider pressure campaigns, may now be more likely to treat volume itself as a red flag. To presume that anyone requesting too much, too fast, must be gaming the system. And the Commissioner, having once elevated coercive access strategy into something noble, has lost the moral authority to insist otherwise.

But the damage goes deeper.

If a court ever reviews a Section 6.1 decision and encounters the inconsistencies between OIC-69 and, say, OIC-60 or CI-47, the entire framework becomes legally vulnerable. Because the law does not permit administrative decision-makers to apply different standards based on intuition, recognition, or unspoken institutional relationships. If two requesters engage in similar conduct and are treated differently—without principled justification—that is, in legal terms, unreasonableness per se.

And the courts won’t miss it. Nor should they.

There is a deeper irony here: in seeking to protect the access system from “abuse,” the Commissioner has created a two-tier regime that is structurally abusive. One where some are above scrutiny, and others are beneath consideration. Where the same behavior will get you rewarded or refused, depending on whether your name has been circulated at access conferences or cited in House committee hearings.

We cannot allow OIC-69 to stand as a model. If left unchecked, it will metastasize into bureaucratic doctrine—a tacit permission structure for discretionary inequality. Every new decision will carry the latent assumption that some requesters deserve the benefit of the doubt, and some don’t. And that is the beginning of the end for Section 6.1 as a lawful tool.

Because law without consistency is not law—it’s preference with a dress code.

By this point, the problem is no longer whether the Commissioner’s Section 6.1 decisions are unreasonable in law. They are. Nor is it merely a question of procedural fairness under Baker. That, too, has collapsed under the weight of opacity and asymmetry. The real question now is: what will be done to stop this?

Because make no mistake: this is no longer a matter of a few bad decisions. The OIC’s Section 6.1 regime has become structurally unsound. Its process is secretive. Its reasoning is conclusory. Its evidentiary record is off-limits. Its decisions are selectively generous. And the entire enterprise is shielded from meaningful challenge by a misapplied interpretation of the Privacy Act that makes judicial review not only difficult, but nearly impossible without a crowbar and flashlight.

So let’s be blunt.

Every single Section 6.1 refusal issued by the Commissioner that rests on vague assertions, inferred intent, or institution-submitted page counts without critical scrutiny should be challenged in Federal Court. Not one of these decisions should be permitted to remain untested. This is not about delay. This is about precedent control. Because the longer these decisions go unchallenged, the more entrenched they become—not just as templates, but as de facto policy. The Commissioner is not just interpreting Section 6.1. She is shaping its future use.

Judicial review serves two purposes here. First, it exposes the logical deficiencies of decisions like OIC-60 and OIC-77, where massive public interest records are denied based on bureaucratic inconvenience. Second, it forces the court to reconcile the preferential treatment evident in OIC-69 with the punitive treatment of everyone else. That kind of comparative analysis is where judicial reasonableness doctrine lives—and where OIC’s inconsistencies are most vulnerable.

If the courts won’t draw the line, no one else will. Parliament has shown no appetite for revisiting the access regime. Institutions are more than happy to offload denial authority onto the OIC. And the OIC, now playing both referee and gatekeeper, shows no intention of correcting herself.

Litigate or be ruled by discretion.

Let’s not pretend Section 6.1 is working as intended. It was sold as a narrowly tailored instrument to filter out serial abusers and preserve institutional resources. What it has become is a selectively enforced gag rule, applied most aggressively to the politically inconvenient and least generously to the procedurally savvy.

If Parliament cannot fix it, it should kill it.

At minimum, Section 6.1 must be amended to include statutory disclosure thresholds—requiring the OIC to publish anonymized but detailed justifications, including:

If the Commissioner cannot do this without violating the Privacy Act, then the law must be amended to explicitly permit anonymized disclosure in Section 6.1 decisions in the public interest. This is not a confidentiality issue. It is a transparency issue. And right now, privacy is being used as a bludgeon against transparency, with the Commissioner holding the handle.

Better yet? Impose a sunset clause on Section 6.1 authority: if the provision continues to be used unevenly, inconsistently, or without publishable justification, it expires. Make the tool earn its keep, or revoke it.

Here’s the unspoken reality: there is no real check on the Information Commissioner short of the courts. There is no independent ombudsman, no disciplinary body, no regularized review of her decision-making standards. In the absence of judicial scrutiny, the Commissioner effectively becomes the final arbiter of what qualifies as access abuse, and she does so in a process that is opaque by design.

This is not a hypothetical problem. The Commissioner’s decisions are often based on representations submitted entirely outside the adversarial process. She does not publish the factual matrix. She invokes privacy to avoid even naming the parties involved. And in cases like OIC-69, she appears to deliberately curate the narrative to present tactical abuse as systemic reform.

That is not oversight. That is narrative laundering.

The fix? Mandatory third-party audits of Section 6.1 decisions every two years, with anonymized case reviews made public. No Commissioner should be permitted to operate a black box regime under the pretense of legal constraint. And if these audits reveal patterns of favoritism, inference-based reasoning, or rubber-stamped institutional deference, then the Commissioner’s own conduct should be subject to review by a legislative or judicial body.

Because if the person tasked with upholding access rights becomes the chief legitimizer of institutional secrecy, the entire regime collapses in on itself.

The rot in the system is not merely procedural. It is ideological.

The idea that certain requesters are “worthy” of access and others are not—that polite, legacy actors deserve accommodation while disruptive or insistent ones deserve refusal—is a cultural pathology. It betrays the entire premise of access-to-information law. Rights do not depend on tone. They are not contingent on familiarity. And they do not require the Commissioner’s approval of your motives.

Yet the OIC’s Section 6.1 regime, as it currently functions, is tone-policed, identity-sensitive, and legacy-biased. It assumes that some people can be trusted with access and others cannot. That is not a legal regime. That is a gated community of permissioned dissent.

The only solution is cultural decoupling: to reassert, loudly and unapologetically, that access rights belong to the public, not to the Commissioner’s Rolodex. If your name is unknown, your request still matters. If your motive is inconvenient, your right still exists. If your volume is high, your burden must still be proved.

Access is a right. The OIC’s behavior suggests otherwise.

That has to end.

The tragedy of the Office of the Information Commissioner is not that it failed to protect access rights.

It’s that it convinced the country it was trying.

For five years, Section 6.1 has operated under the pretense of balance—a mechanism to protect institutions from abuse while preserving the public’s right to know. But the decisions analyzed here show nothing of the sort. What we find instead is a pattern of procedural vagueness, deference masquerading as reasoning, and a bureaucratic instinct to side with institutions at every fork in the road. The Commissioner has not just tolerated this drift. She has authored it.

The OIC is no longer an oversight body. It is an intermediary liability shield—a final firewall between the Canadian public and the truths buried inside the federal apparatus. By approving institutional refusals through generic reasoning and inaccessible evidentiary records, the Commissioner offers the state a service: denial with plausible deniability, censorship with jurisprudential cover.

And when it counts most—when a seasoned actor exploits the system to overwhelm a department with 600 coordinated access requests in a self-confessed campaign of statistical manipulation—the Commissioner does not condemn it. She rationalizes it. She names no one. She shields the facts. She drowns the coercion in context.

This isn’t just discretion. It’s complicity.

Worse, it’s performative complicity: a bureaucracy that wears the robes of lawfulness while engaging in a functionally autocratic act—denying rights based on identity, tone, or institutional friction. The Access to Information Act has become a managed illusion, and the Commissioner its stage manager.

One might ask: where are the courts? The answer, of course, is buried under redactions, inaccessible reasoning, and the time-cost of judicial review—barriers engineered not by accident, but by design. The Commissioner does not expect her decisions to be challenged. She relies on the friction of the process to protect her.

That protection must end.

Section 6.1 is not fixable through guidance. It is not salvageable through training. It is a structurally corrupted instrument, deployed under the cover of administrative law but rotted through by bias, opacity, and a quiet contempt for the very people it affects.

The Commissioner will not change this. She cannot. Her office is entangled in the very culture it was created to restrain. The only remaining path is litigation, exposure, and—ultimately—replacement.

Because the greatest threat to transparency in Canada is not state secrecy.

It is the belief that someone is watching when no one is.

The author of this article is not a disinterested observer of Canada’s federal access-to-information regime. He is:

This piece was not written in a vacuum. It was written in the smoking crater of what used to be called “oversight.”

No attempt has been made to disguise the tone.