Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) – the collection and analysis of publicly available information – has long been an underappreciated stepchild of the intelligence family. Historically, glamorous secret sources (spies, intercepted cables, satellites) stole the limelight, while OSINT quietly supplied background context from newspapers, broadcasts, or academic journals. Yet the digital age unleashed a tsunami of open data: social media posts, commercial satellite imagery, corporate records, online forums, and more. In conflicts and crises from the Arab Spring to the Russia-Ukraine war, OSINT emerged from the shadows, proving its worth by uncovering facts in real time that rival traditional classified sources. The discipline is “coming of age,” evolving from laborious manual clipping of newspapers into a high-tech domain leveraging big data and AI analysis.

This maturation of OSINT is forcing a paradigm shift in national security. Intelligence agencies, traditionally obsessed with secrecy, now face a world where secrets often hide in plain sight among promiscuous public data. As one former CIA acting director observed, OSINT is increasingly seen as the “INT of first resort” rather than a mere supplement. Fittingly, after decades of playing second fiddle, OSINT is now being institutionalized at the highest levels of U.S. intelligence oversight. In early 2025, the U.S. House of Representatives’ Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) created a new Subcommittee dedicated exclusively to OSINT – the first ever congressional body devoted to this once-neglected discipline. The move signals that open-source intelligence is no longer an afterthought; it’s becoming a cornerstone of modern intelligence practice.

Why now? A convergence of factors made OSINT impossible to ignore. The sheer volume and velocity of publicly available information in today’s threat landscape offer both great opportunities and new challenges for intelligence agencies. From tracking disinformation campaigns to forecasting geopolitical moves through commercial satellite photos or aggregating social media sentiment, OSINT can reveal insights that secret methods might miss or obtain too slowly. At the same time, adversaries from terrorist groups to authoritarian states are themselves exploiting open data – prompting Western policymakers to ensure they don’t fall behind. High-profile successes of investigative outlets like Bellingcat (which identified Russian operatives through open data) have showcased OSINT’s power, even as cautionary tales of missteps (such as false attributions based on sketchy social media posts) highlight the need for rigorous tradecraft. Thus, institutionalizing OSINT is about maximizing its value while mitigating its risks. This report will analyze the creation of the HPSCI OSINT Subcommittee and assess its strategic implications: how it reshapes intelligence oversight in the U.S., what parallels exist abroad, and how it might redefine the relationship between government spymasters and private open-source sleuths.

The establishment of the OSINT Subcommittee in the House Intelligence Committee marks a historic inflection point. Announced in February 2025 at HPSCI’s first meeting of the 119th Congress, the subcommittee’s mandate is clear: oversee and legislate for the Intelligence Community’s open-source intelligence programs, policies, and budgets. In practical terms, this means a dedicated group of lawmakers will scrutinize how U.S. intelligence agencies collect commercially and publicly available information, how they analyze and share it, and how they integrate OSINT into the broader intelligence cycle. Such oversight had previously been scattered across other subcommittees or handled ad hoc. By carving out a standalone subcommittee, Congress signaled that OSINT requires focused attention and tailored governance, distinct from classic spycraft disciplines.

Fitting into the HPSCI Structure: The OSINT Subcommittee joins a roster of specialized HPSCI panels that typically align either by agency or functional domain. In the 119th Congress, HPSCI also has subcommittees for the CIA, for the National Security Agency & Cyber, for Defense Intelligence & Overhead (satellites), and others. Unlike those, which correspond to major agencies or well-established intel realms (SIGINT, GEOINT, etc.), the OSINT Subcommittee is unique in focusing on a cross-cutting discipline spanning all agencies. This gives it a potentially sweeping purview – “programs, policies, and budget authorization for the Intelligence Community’s Open-Source Intelligence discipline” – essentially any OSINT effort in any part of the IC falls under its eye. The subcommittee can call hearings, demand reports, and shape legislation specific to open-source issues, ensuring that initiatives like the CIA’s Open Source Enterprise or the Defense Intelligence Agency’s OSINT units get the congressional guidance and resources they need. It institutionalizes OSINT oversight in a way that never existed before, addressing an oversight gap that had grown more glaring as OSINT’s profile rose.

Who’s Driving It: The subcommittee is led by Chair Rep. Ann Wagner (R-MO) with Rep. Chrissy Houlahan (D-PA) as the Ranking Member – a bipartisan pairing reflecting broad agreement on elevating OSINT. Rep. Wagner, a former diplomat, has emerged as a key champion. Upon her appointment, she emphasized that “open-source intelligence is essential for a wide audience of policymakers… who gain situational awareness without relying on classified sources.” In her view, America’s adversaries are collaborating in new ways, posing complex threats, and OSINT helps the U.S. better understand “the volatile playing field” of modern geopolitics. HPSCI Chairman Rep. Rick Crawford (R-AR), who created the subcommittee, echoed that OSINT is a “growing and complex area” and that HPSCI needed to recalibrate oversight to keep up. Both Wagner and Crawford have highlighted the need for “appropriate policy and governance, resources, and standardized training and tradecraft” so that OSINT capabilities can fully mature within the IC. These stated priorities give a hint of the subcommittee’s agenda: crafting policies to standardize how agencies handle open-source data, pushing for budgets to expand OSINT capabilities, and professionalizing the OSINT workforce through training and tradecraft standards.

Notably, external voices and events provided momentum. Thought leaders like Michael Morell (ex-CIA chief) and Amy Zegart (Stanford/Hoover scholar) had been publicly urging Washington to take OSINT more seriously – even proposing a dedicated agency for it. Their argument: in an era where “secret agencies will always favor secrets,” intelligence will only succeed if open-source information is made foundational – which in turn requires a dedicated organizational focus. The bipartisan consensus in Congress, rare in intelligence matters, indicates lawmakers heard this message. From concerns over Chinese spy balloons to Russian info-war operations, members have repeatedly seen OSINT serve up insights (or catch failures) in headline-grabbing ways. Creating the subcommittee was a way to get ahead of the curve, ensuring the IC isn’t “inexplicably slow” in harnessing open data – a criticism leveled by a 1990s commission and sadly still relevant decades later.

Mandate and Early Actions: Since its formation, the OSINT Subcommittee has embarked on a fact-finding blitz. Its jurisdiction covers everything from how the CIA’s Open Source Enterprise mines foreign social media, to how the NSA might use open web data to complement signals intercepts, to how the Defense Department uses commercial satellite imagery or purchased databases. In April 2025, Chair Wagner convened a roundtable with private-sector OSINT companies to learn what capabilities they offer the IC. The invite list – including a threat intelligence firm (Recorded Future), a commercial data marketplace (Grist Mill Exchange), a China-focused analytics platform (WireScreen), and a deepfake detection startup (Reality Defender) – speaks volumes. Wagner’s takeaway was that OSINT is “unlocking new opportunities for the IC” and as a “maturing discipline” the government must be smart about how it buys data and tech from these providers, standardizing contract structures across agencies. This indicates one immediate focus area: procurement and integration of Commercially Available Information (CAI). The subcommittee explicitly frames much of OSINT in terms of CAI – the legally purchasable data ranging from satellite imagery to bulk news feeds – and aims to ensure the IC coordinates these purchases efficiently. Standardizing contracts might prevent duplication (multiple agencies buying the same dataset separately) and enforce security or privacy vetting of vendors.

Within weeks of its launch, the subcommittee members were also out in the field. In May 2025, Rep. Wagner led a bipartisan delegation to Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) headquarters to see how OSINT supports military operations. The visit focused on how open-source info is used to aid warfighters and “ensure a robust national security posture,” underscoring that OSINT isn’t just academic research – it can have real-time tactical value on the battlefield. The subcommittee also took its oversight abroad: Wagner traveled to Europe and the Middle East to discuss OSINT with allies, and even to Japan to meet counterparts in intelligence. This globe-trotting underscores the strategic imperative the subcommittee sees: ensuring the U.S. and its friends are leveraging OSINT effectively worldwide. By publicly highlighting these trips, HPSCI also sends a message to the IC: we expect progress on OSINT, and we’re watching.

How OSINT Oversight Differs: In Congress, specialized subcommittees for intelligence disciplines are quite new. Historically, HPSCI panels were organized by agency (e.g. separate ones for CIA, NSA, etc.) or by broad mission (like counterterrorism, emerging threats). There wasn’t, for example, a permanent “HUMINT Subcommittee” overseeing espionage or a “SIGINT Subcommittee” just for signals intercepts – those fell under agency-focused panels (CIA, NSA) or functional groupings. The OSINT Subcommittee is thus a novel construct. This reflects OSINT’s cross-agency nature: unlike HUMINT or SIGINT which tend to be the remit of specific agencies, open-source collection is done by many parts of government. Congress evidently concluded that only a dedicated subcommittee could corral this diffuse activity into a coherent picture.

One key difference in OSINT oversight is the blurring of lines between classified and public domains. Traditional intel oversight happens behind closed doors (in secure facilities, reviewing secret programs). But OSINT, by definition, deals with unclassified info. The subcommittee’s challenge – and opportunity – is to conduct much of its discussion in the open. Indeed, an initial priority is figuring out how to make more unclassified OSINT products available to officials outside the IC and even to the public. A bill introduced in parallel with the subcommittee’s launch, the Open Source Intelligence Availability Act, calls on the DNI to develop a plan to disseminate unclassified OSINT reports to federal agencies and even state/local governments who could benefit. The existence of such a bill shows lawmakers want OSINT to break out of the silos: no more intelligence reports gathering dust simply because they sit on classified networks unnecessarily. The subcommittee can be a catalyst for this cultural change, pushing the IC to publish what can be published. Chairman Crawford explicitly noted that leveraging OSINT effectively will help deliver intelligence to America’s leaders while “protecting against abuses of powerful tools” – a nod to the delicate balance of exploiting open info without infringing on rights (more on that in Section 5).

In summary, the OSINT Subcommittee’s role is part cheerleader, part taskmaster. It legitimizes OSINT as a core intelligence discipline in need of strategy, investment, and oversight at the highest level. Its early activity – industry roundtables, agency visits, international engagement – indicates a wide-ranging remit from improving tradecraft and procurement to fostering public-private partnerships. By elevating OSINT’s status inside the Capitol, Congress is essentially telling the IC: the era of OSINT has arrived – adapt or fall behind. And notably, this U.S. move is not occurring in isolation; allies and even adversaries are also structuring themselves to harness open-source information, as we examine next.

The United States is not alone in grappling with how to institutionalize OSINT. Around the world, intelligence communities and policymakers are exploring ways to organize and oversee open-source capabilities. Some democracies are cautiously following America’s lead, while others had already baked OSINT into their structures in quieter ways. Meanwhile, authoritarian regimes, free from public oversight, aggressively exploit OSINT but keep those efforts opaque. This section surveys key parallels across allies and adversaries, highlighting how open-source intelligence is gaining formal standing – or being weaponized – beyond U.S. borders.

Five Eyes Allies (Canada, UK, Australia, NZ): Among America’s closest intelligence partners, none so far have created a dedicated parliamentary subcommittee for OSINT as the U.S. House did. However, there are signs of movement. In Canada, OSINT activities have grown within the Canadian Forces and security agencies, attracting the attention of oversight bodies. Canada’s intelligence apparatus historically kept a low profile on OSINT, but internal advocates have argued it should be elevated. A 2024 Canadian Forces paper lamented “overly ad hoc” approaches and urged that OSINT be resourced as a foundational discipline on par with others, to ensure a robust joint capability for the military In practice, Canadian Forces Intelligence Command (CFINTCOM) produces daily OSINT summaries and has small cells devoted to open-source analysis (often for situational awareness in missions). Yet these efforts lack a formal unified structure or public profile. Tellingly, Canada’s independent watchdog agency, the NSIRA, launched a review in 2025 of DND/CAF’s OSINT activities to examine their “reasonableness, necessity, and compliance” with laws and policies. This indicates some formalization – at least in oversight. NSIRA’s review, addressed to the Defence Minister, suggests an increasing transparency: even though OSINT deals with public info, Canada wants to ensure its military’s open-source spying doesn’t run roughshod over privacy or other rules. The mere fact of a public notice about investigating OSINT usage implies a move to formalize and possibly set guidelines for Canadian OSINT practices. However, no dedicated OSINT center or legislative body exists yet. Canadian parliamentarians through NSICOP (the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians) keep an eye on all intelligence disciplines, but OSINT hasn’t received a separate treatment in their reports beyond acknowledging it as one of the “full spectrum of intelligence activities” DND/CAF can conduct. We might anticipate that if the U.S. subcommittee uncovers best practices or recommends closer integration of allied OSINT sharing, Canada could respond by creating a more explicit OSINT strategy or coordinator role in its own agencies.

The United Kingdom, with its storied MI6, MI5, and GCHQ, traditionally put far less publicly acknowledged emphasis on OSINT. British intelligence did (and does) use open sources – for instance, BBC Monitoring, a unit that has for decades listened to foreign broadcasts and shared that info with UK agencies. BBC Monitoring can be considered an OSINT unit (open-source information from media) that is unusually placed under the BBC, and thus partly open and accessible (and indeed providing reports to customers beyond government). More recently, the UK Ministry of Defence’s Defence Intelligence arm has been beefing up open-source capabilities. There are references to an “OSINT hub” or centralizing effort within Defence Intelligence, especially after lessons learned from conflicts like Ukraine. In 2022, a RUSI study noted that UK national security agencies had an opportunity to invest in “standardised OSINT support structures – with integrated systems, processes…”. It implied the UK was still fragmented in OSINT approach. Since then, the MOD has solicited industry input on an “enterprise OSINT capability,” suggesting an intention to build a formal, possibly centralized OSINT system to serve the military and beyond. Indeed, Defence Intelligence (DI) reportedly stood up an Open Source Intelligence Hub in recent years, though details are scant (likely classified). What’s known is that DI has been hiring OSINT analysts and using tools to monitor social media and online data relevant to military operations. The UK’s parliamentary oversight (the ISC) rarely discusses OSINT explicitly in its public reports, reflecting an older mindset where open sources were considered simply one input to analysis rather than a separate program needing oversight. However, given how OSINT about Russian troop movements (via commercial satellites and TikTok videos) proved invaluable ahead of the Ukraine invasion, one can imagine UK officials quietly ensuring their National Intelligence Machinery adapts. The UK also has the JTAC (Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre) and other fusion centers that rely on open info combined with classified – but again, these efforts aren’t labeled “OSINT” publicly. Cultural change may be slower in London, but the pressure of reality (and likely friendly nudges from Washington) is pushing them toward more formal OSINT integration.

In Australia, OSINT is explicitly part of the intelligence community. The Office of National Intelligence (ONI) – Australia’s DNI equivalent – includes an Open Source Centre that provides open-source support to all agencies. This Open Source Centre (formerly under the Defence Intelligence Organisation, now under ONI) is a recognized unit that produces unclassified and classified OSINT reports. Its creation shows a formal institutional approach, though we don’t see Australian Parliament committees dedicated solely to OSINT. Similarly, New Zealand and smaller Five Eyes members leverage open sources but within existing structures. They tend to incorporate OSINT into all-source analysis without separate bureaucratic entities. Still, all Five Eyes now share certain OSINT products and best practices informally. Notably, NATO’s Kabul operations and the war on terror saw allied intelligence units routinely use OSINT (e.g. jihadist web forums, local media) – so at the working level, OSINT cooperation is not new. What is new is the push to formalize it at policy level, as the U.S. has now done.

NATO and European Institutions: The multilateral arena offers examples of institutionalizing OSINT in creative ways. NATO itself, while a military alliance, has increasingly acknowledged OSINT’s value for coalition situational awareness. A 2024 Atlantic Council report by a former NATO general bluntly argued NATO must “embrace OSINT enabled by AI” to detect threats, lamenting underinvestment and a culture too biased towards classified sources. In fact, NATO has set up specialized cells to handle open-source info. During operations, NATO’s intelligence fusion centers include OSINT sections that compile open data on conflict zones. Recently, NATO created a “Hybrid Analytics” cell (unofficially described as a hybrid threats OSINT cell) to monitor things like propaganda, cyber activities, etc., often in tandem with the EU.

The European Union, lacking a traditional spy agency, has leaned heavily on open sources for its shared situational awareness. A notable body is the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell, established in 2016 within the EU Intelligence and Situation Centre (INTCEN)ruj.uj.edu.pleumonitor.nl. This cell’s mission is to provide strategic analysis on “hybrid threats” – a broad umbrella including disinformation, cyberattacks, covert operations, and influence campaigns that mix military and civilian tactics. The Hybrid Fusion Cell fuses information from member states’ intel services and OSINT to identify hybrid threat indicators. For instance, it analyzes social media trends for disinformation spikes, or compiles open reports of unusual drone sightings, etc., across Europe. It operates relatively transparently for an intel unit: EU officials have publicly referenced its reports in discussions about foreign disinformation. The HFC is essentially an institutional OSINT hub at the multinational level. It has also cooperated with NATO’s own hybrid analysis unit, sharing open-source findings on things like election interference attempts. How formalized is it? It’s integrated into the EEAS (EU External Action Service) and issues strategic situational reports to EU policymakers. But being in a political union, its outputs are often for consumption by member states and EU bodies rather than covert action. The existence of HFC shows recognition that open-source analysis is critical for anticipating hybrid threats, which often manifest first in the information domain. This is an area the U.S. OSINT subcommittee will likely watch closely – hybrid threat intelligence blurs lines between foreign and domestic information, raising tough oversight questions.

Another European example: EU vs Disinfo, a project of the EU East StratCom Task Force, systematically collects and debunks disinformation (largely from Russian sources). It’s not “intelligence” per se, but a public-facing open-source monitoring operation funded by the EU to strengthen information security. Its reports, while not secret, feed into the broader understanding of adversary narratives. This quasi-OSINT function under a diplomatic service umbrella highlights how democracies use open data for strategic communications and policy, not just for classic espionage.

Case study – UK’s Defence Intelligence OSINT Hub: To illustrate the UK’s approach, consider a hypothetical (but realistic) scenario: After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, UK’s DI set up an OSINT Hub to track the conflict. Analysts in this hub scour commercial satellite imagery for Russian troop deployments, analyze TikTok videos posted by civilians for clues about military movements, and monitor Telegram channels for ground reports. They use AI tools (some from private UK firms like Adarga or faculty from the Alan Turing Institute) to sift through millions of social media posts and sensor data. The hub then produces daily unclassified updates on battlefield changes and adversary propaganda lines, which can be shared with allies or even publicly to counter Russian claims. UK officials have alluded to such capabilities, and indeed have occasionally declassified intelligence about the war sourced from OSINT (e.g., pointing to open-source satellite images to dispute Russian denials of civilian harm). The transparency is limited, but there’s an evident formalization: what was ad hoc in 2014 (during Crimea) became organized by 2022, with a structure, budget, and purpose. It remains to be seen if Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee will ever discuss the OSINT hub in open session – but the UK government did openly credit “intelligence, including publicly available information” in its security briefings about Ukraine. This subtle shift indicates OSINT’s growing formal acceptance.

Case study – Canada’s OSINT initiatives: In Canada, beyond the military, the civilian intelligence wing (CSIS) and signals agency (CSE) have started leveraging OSINT for things like monitoring extremist online content and protecting research security. The Canadian government launched initiatives to use open-source due diligence tools to protect academia from espionage. Also, Canada’s Centre for Security, Intelligence and Defence Studies (CSIDS) has an entire program examining OSINT, involving academics and practitioners to refine methodologies. These are signs of a country trying to catch up on OSINT know-how and formalize it through training and doctrine, even absent a flashy new agency or law. But with the U.S. making OSINT a priority, Canada will almost certainly feel pressure to coordinate and formalize its efforts – not least because Canada relies on intelligence sharing where open-source info from the U.S. could be a bigger component. If the U.S. starts pushing more OSINT products out (as H.R. 6329 envisions), Canadian agencies will want to be sure they can receive, use, and contribute to that flow effectively.

Authoritarian States and OSINT: On the flip side, countries like China and Russia approach OSINT in markedly different fashion – often embracing it wholeheartedly behind closed doors while publicly denying or downplaying those capabilities. In China, open-source intelligence is actually considered the primary source in many contexts, given the relative scarcity of China’s human spy networks compared to the abundance of open Western data. Chinese military writings frequently extoll the value of “military public opinion analysis” and using open information to glean insights about foreign militaries. A recent study found that the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) has developed a whole ecosystem of private companies, state institutes, and tech platforms to collect and process OSINT for military use. These include firms specializing in big data mining, AI-driven analysis of global media, and even companies purchasing commercial datasets on behalf of the Chinese state. The PLA’s goal is clear: exploit the West’s open information environment to the fullest, since Western militaries “must contend with China’s closed environment” and thus Beijing sees a one-way advantage. For example, Chinese analysts vacuum up everything from Western think-tank papers and military journals to social media chatter by U.S. service members – all to piece together intelligence. Nothing in Chinese law prevents buying Western commercial data or scraping websites, so they do so aggressively. One result: China can often understand U.S. and allied military developments through OSINT faster and cheaper than the reverse. The PLA openly (in internal circles) calls for “harnessing new technologies” for OSINT and even mobilizing civilian organizations (scholars, state media, tech firms) to support the cause. There’s essentially a public-private fusion in Chinese OSINT efforts – mirroring their approach in tech generally. But there’s no transparency: these activities are cloaked under innocuous fronts (research institutes, university programs) and certainly no parliamentary oversight (since none exists in a one-party state). The implications are stark: authoritarian OSINT is a state-sponsored vacuum cleaner sucking up global data without constraint. This reality is not lost on U.S. policymakers. The Cipher Brief op-ed by Borene and Saelinger pointed out that adversaries like China and Russia have “no limits” in using mass data theft, scraping, and purchase of private data on Americans. They warned it would be “devastating” if U.S. agencies couldn’t leverage equivalent open-source data due to overregulation. In other words, authoritarian exploitation of OSINT is one driver for the U.S. to double down on its own open-source capabilities – lest it unilaterally disarm in this arena.

Russia, for its part, has a long history of OSINT in the form of state media monitoring and active measures. The Soviet KGB devoured open publications from the West, and today Russian intelligence benefits from open internet access to target audiences. While Russia’s intel structure remains secretive, there are known entities like the Internet Research Agency (the infamous troll farm) which, beyond pushing propaganda, also analyze social media trends (open data) to refine their influence operations. Russian military intelligence (GRU) likely has units dedicated to scraping forums and social networks for useful intel (for example, during conflicts to geolocate targets via soldiers’ smartphone posts). In the Ukraine war, both Russian and Ukrainian forces scoured TikTok, Telegram, and Twitter for OSINT on each other – but the Russians also learned the hard way how OSINT exposes them, as online communities like Bellingcat or Ukrainian volunteers unmasked many of Moscow’s covert activities. The Kremlin’s approach thus has been paradoxical: exploit OSINT for offense, but suppress or manipulate it defensively. Domestically, Russia tightly controls open information (shuttering independent media, blocking OSINT sites) to deny adversaries useful data and to prevent its own citizens from doing OSINT on Russian government malfeasance. It’s a reminder that authoritarian regimes treat information as a battlefield – they will vacuum others’ open data but shield their own, a fundamentally asymmetrical situation.

Other States: Many other countries are following suit in quieter ways. For example, India in recent years set up an “Open Source Intelligence Branch” within its external intelligence agency RAW to monitor social media in neighboring countries and track terrorist propaganda. Israel has long used OSINT (e.g., its intelligence watched Arab TV broadcasts and newspapers assiduously), and in the cyber era Unit 8200 (SIGINT) analysts also take in open web data alongside hacks. The difference is mostly one of openness: Western democracies are starting to openly acknowledge and structure OSINT efforts (as seen by U.S. and EU steps), whereas more closed regimes simply do it without fanfare or oversight.

Transparency and Formalization: The question of transparency is crucial. The U.S. OSINT subcommittee operates in a democracy, so we see press releases, public quotes, even perhaps unclassified hearings in the future. Allies like the UK or Canada have not yet reached that level of openness about OSINT – which could indicate their efforts remain relatively nascent or politically sensitive. For instance, if Canada were to create an “OSINT Coordinator” position, one could foresee NSICOP (the Parliamentarians’ intel committee) eventually mentioning it in a report, thereby giving the public a peek. If the UK’s ISC were persuaded by the government to examine OSINT integration, we might get a sanitized public summary about it. But until now, much of the allied OSINT development is gleaned only through think-tank reports and industry chatter.

In NATO/EU, some transparency exists – EU officials talk about the Hybrid Fusion Cell in conferences, NATO generals speak at think tanks about OSINT’s importanceatlanticcouncil.orgatlanticcouncil.org. This multilateral transparency is part of building consensus among many countries. Interestingly, that dynamic can even push nations to be more open: for example, NATO intelligence bodies circulated OSINT findings on Russian disinformation to all 30 allies, which include countries with strong free press traditions, making it harder to keep those completely secret. The U.S. subcommittee may encourage even more openness, for instance by urging the release of unclassified OSINT products to NATO partners or to the public to debunk adversary narratives.

In summary, global counterparts show a spectrum: from institutionalized OSINT centers within intel agencies (Australia’s Open Source Centre, EU’s Fusion Cell), to nascent moves to formalize (UK MOD’s efforts, Canada’s oversight reviews), to full-steam exploitation with zero transparency (China, Russia). The creation of the U.S. OSINT Subcommittee arguably puts Washington at the vanguard of publicly formalizing open-source intelligence oversight. It sets an example that allies may emulate in their own way – perhaps not carbon-copy subcommittees, but new policies and units – and sends a message to adversaries that the U.S. intends not only to catch up but to lead in the OSINT domain.

One of the most intriguing impacts of “mainstreaming” OSINT is how it will transform the ecosystem of private-sector intelligence firms and independent OSINT practitioners. The line between government intel agencies and private sources of intelligence has been blurring for years – from contractors providing analysis, to companies selling data and even publishing their own intel reports (e.g. cybersecurity firms attributing hacks). A congressional subcommittee shining a spotlight on OSINT will accelerate this convergence. Here’s how:

Procurement and Market Opportunities: The U.S. OSINT Subcommittee is already scrutinizing how agencies acquire open-source data and tools, with an eye toward smarter procurement. This likely means more (and more standardized) contracts with private OSINT vendors. When Chair Wagner says “ensure we are standardizing contract structures” for purchasing data across agencies, it implies the government will craft common requirements and perhaps bulk purchasing agreements. For private companies, this could be a boon: the intelligence community might adopt a centralized OSINT acquisitions program that awards multi-agency contracts to, say, a suite of data providers. Instead of a small pilot contract here or there, companies could land enterprise-wide deals. Indeed, the OSINT Subcommittee’s engagement with firms like Recorded Future, Babel Street, Janes, etc., suggests Congress wants to understand the marketplace so it can encourage the IC to take advantage of it. The subcommittee can also advocate for budget plus-ups in the annual Intelligence Authorization Act specifically for OSINT procurement – effectively steering government dollars toward the private OSINT sector. For example, they might recommend a fund for purchasing social media monitoring services or satellite imagery analysis on demand.

The flip side is increased scrutiny. If more taxpayer money flows to private OSINT, Congress will demand accountability on performance and value. Vendors that overhype capabilities will be called out. Already, there’s awareness that some tools promise AI-magicked “insights” but deliver dubious results. The subcommittee’s public–private roundtable was as much about due diligence as exploration – members asked candid questions on “what is and is not working when doing business with the IC.” This signals to industry: be prepared to show proof of concept and measurable impact. The end of the Wild West era may be nigh; structured partnerships will prevail.

Standards of Tradecraft and Compliance: A major theme likely to emerge is the development of standards for OSINT tradecraft and legal–ethical compliance. Intelligence tradecraft (the methods and standards analysts use) in OSINT is still evolving. Unlike well-honed standards for handling secrets, there is no decades-old playbook for validating a viral video’s authenticity or quantifying the reliability of a Twitter source with an anime avatar. The OSINT Subcommittee, by virtue of existing, creates impetus for the IC to formalize such standards. ODNI has already released a new Intelligence Community Directive specifically about producing and disseminating unclassified, OSINT-derived analytic products. According to an OSINT Foundation update, ODNI issued guidance in late 2024 to standardize OSINT discipline and foster IC-private sector partnerships, reflecting a push for consistent practices across agenciesosintfoundation.com. We can expect more to come: possibly an IC Tradecraft Manual for OSINT akin to those that exist for all-source analysis. This might cover source verification steps, citation standards (e.g. ensuring even internal OSINT reports reference the open sources clearly), and grading of source reliability. In fact, the OSINT Foundation noted an IC policy on OSINT citations was being updated, which would help analysts properly credit and evaluate the open data they use.

From a compliance angle, data protection and privacy laws loom large. Private OSINT companies have to navigate terms of service of platforms, copyright issues for scraping content, and laws like Europe’s GDPR if they handle personal data. As Congress encourages OSINT use, it may also seek to ensure such use is legally sound and ethically sourced. We might see recommendations that the IC only contract with companies that adhere to certain guidelines (for example, not breaking website terms of service without approval, or not inadvertently ingesting U.S. persons’ data in violation of regulations). There’s even talk in the community of establishing ISO standards for OSINT – essentially formal certifications that an OSINT provider follows best practices in collection, storage, and analysis. If these emerge, government contracts could require them. This professionalization would benefit serious players but might marginalize the more freewheeling lone-wolf operators who can’t demonstrate compliance infrastructure.

Cooperation vs. Competition (Public Agencies & Private Firms): Historically, there was sometimes tension – agencies viewed outside OSINT with skepticism (“Can a bunch of journalists with laptops really do intel analysis as well as we do?”) while some private outfits marketed themselves as alternatives to three-letter agencies. But the gap is closing. The subcommittee’s stance is clearly pro-collaboration: it literally brought industry into the Capitol to “showcase capabilities” to lawmakers. By doing so, it implicitly validates those companies’ role in supporting national security. Cooperation is poised to deepen in several ways:

However, competition won’t vanish. Some private intelligence firms might leverage the new attention on OSINT to assert their relevance (perhaps lobbying Congress to outsource more OSINT work). If government is seen as slow, a firm might publish high-profile OSINT reports (e.g., identifying a war crime via satellite image before the CIA does) to essentially shame the IC or win contracts. Conversely, agencies might build internal capabilities that compete with what companies sell. For instance, if the subcommittee pushes for a National OSINT Agency or Center, that entity might take on tasks currently done by contractors, potentially reducing some markets. The likely outcome, though, is a symbiosis: agencies focus on inherently governmental functions (like classified+OSINT fusion, or sensitive targeting decisions) and rely on private feeds and analyses for broad monitoring and niche expertise.

Firms like Bellingcat and other investigative collectives represent an interesting case – they often operate as public interest journalism, not traditional vendors. Could the subcommittee’s work lead to closer cooperation with such entities? Possibly indirectly. While Bellingcat might not become a contractor (for objectivity reasons), the IC could follow its findings more systematically. The mere legitimacy that OSINT now has might mean an analyst at CIA can cite a Bellingcat report in an intelligence assessment without fear of ridicule. In fact, the new openness may encourage the IC to quietly support these independent groups (perhaps via grants or shared tools). There is precedent: Bellingcat has trained NATO analysts in open-source techniques, showing the knowledge transfer can flow both ways.

Normalization of Private Contributions: A fundamental shift on the horizon is that private-sector OSINT contributions could become officially integrated into the intelligence cycle. One could foresee a day when the President’s Daily Brief (PDB) contains, alongside secret intercepts, a graph from a private social media analysis or a fact from an academic OSINT report. As mentioned earlier, legislation is pushing for OSINT products to be shared more widely in government. This implicitly treats unclassified OSINT analysis as something every policymaker should see – breaking the old model where only classified = valuable. The subcommittee might even recommend that the National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) process incorporate open-source annexes that draw on outside experts.

In practical terms, normalization could mean:

One must note a caution: If private intel firms become deeply embedded, issues of accountability and secrecy arise. A private company working closely with an intel agency may gain access to sensitive information or tasks. Ensuring they operate under proper oversight (and don’t misuse data or violate rights) will be essential – an area where the subcommittee will certainly keep watch. We might see new compliance requirements in contracts or even new laws covering “commercial intelligence providers” to formalize their obligations.

Pressure on Allies (Canada example): The user’s prompt specifically asks: will Canada face pressure to formalize a similar OSINT oversight framework, given its reliance on OSINT and U.S. sharing? Likely yes. When the U.S. sneezes, Canada often catches a cold in intel policy. If the U.S. subcommittee leads to big strides (like a national OSINT strategy, more open sharing), Canada risks being left behind if it doesn’t also adapt. Already, Canada leans heavily on U.S. intelligence for national security. If more U.S. intelligence comes in the form of OSINT products, Canadian agencies must be equipped to receive, analyze, and act on them. Canada might not copy a parliamentary subcommittee – its system is different – but it could respond by:

Furthermore, Canada might feel pressure on the private sector side: Canadian companies in the OSINT space (if any – there are a few startups and research outfits) could gain opportunities if Canada ups its spending. Conversely, if Canada lags, its own intel could become increasingly second-hand, essentially just consuming U.S. OSINT findings without contributing much back. Politically, being a net consumer could be uncomfortable. Expect Canadian officials to at least discuss whether they need an “OSINT strategy for Canada” to keep pace.

Finally, ethics and competition: Private OSINT actors – be they firms or journalists – will also have to navigate ethical boundaries as they become more entwined with states. For instance, Bellingcat fiercely guards its independence; it might worry that too much coziness with governments could compromise its credibility or even endanger staff by painting them as spies. Private companies, on the other hand, might face conflicts of interest if they serve both government and corporate clients (e.g., a firm that provides geopolitical OSINT to the CIA and also to multinational corporations – are there firewall issues if interests diverge?). As OSINT is normalized, such questions will need answers. The subcommittee could conceivably recommend a code of conduct for private intel firms or even a licensing regime (though that would be controversial).

In summary, the mainstreaming of OSINT heralds a new era of public-private intelligence symbiosis. We will likely see a booming market for OSINT tools and services, but also more oversight and standardization shaping that market. The best private practitioners stand to gain legitimacy and business, while those cutting corners may be exposed. Ultimately, national security outcomes should improve if the “hive mind” of private and public analysts can be harnessed. A senior U.S. official recently noted that partnerships led to decisions that “ultimately save lives, solve investigations, uncover plots, [and] thwart fraud” – none of which would be possible if government and private sectors stayed in separate silos. The OSINT Subcommittee seems determined to tear those silos down (or at least punch holes in them), integrating the collective wisdom of all who can contribute to America’s situational awareness.

As OSINT becomes institutionalized, it collides with big policy questions – notably the role of artificial intelligence in intel gathering, the balance between surveillance and civil liberties, and even the need for new legal definitions. The House’s OSINT push is happening against a backdrop of intense debates over AI and privacy, making it both an opportunity to modernize intelligence and a potential flashpoint for civil liberties advocates. This section examines how the OSINT Subcommittee’s work intersects with these broader issues.

AI in Intelligence Gathering: Advanced algorithms and machine learning are double-edged swords for OSINT. On one hand, AI is a godsend to cope with the massive scale of open data. No human can read millions of tweets or analyze hours of CCTV footage daily, but AI can flag patterns, identify faces, translate languages – essentially act as an amplifier for analysts. The subcommittee’s interest in private tools indicates they see AI as key: firms demonstrated AI-driven solutions like Recorded Future’s Intelligence GraphⓇ that fuses threat data to “see the complete picture,” or Reality Defender’s multimodal AI to detect deepfakes. These examples show AI being used to filter noise, connect dots, and discern truth from fabrication. Indeed, a NATO-focused analysis emphasized that OSINT enabled by AI can help detect adversary moves and influence ops far more effectively. The U.S. IC knows this: the DNI’s tech priorities and DoD’s OSINT Strategy 2024-2028 both feature AI/ML to automate open-source collection and analysis.

However, the subcommittee must grapple with AI’s pitfalls: bias, error, and manipulation. AI models are trained on existing data, which may carry biases – thus an AI tool might overlook threats that don’t fit historical patterns or might misidentify innocent behavior as malicious if the training data was skewed. Moreover, adversaries can engage in adversarial manipulation – poisoning the well of open data to fool AI. For example, a state actor might flood social media with noise or fake geolocation signals to throw off an AI that predicts troop movements based on social posts. There’s a scenario often discussed: if spies know the U.S. relies on AI to analyze open sources, they could create carefully crafted “troll data” to exploit algorithmic weaknesses (much like hackers trick AI vision by subtly altering images). OSINT oversight must ensure the IC is aware of these risks and has mitigation plans. That could mean requiring that human analysts stay in the loop – using AI for triage but not final conclusions. It also means investing in AI transparency: understanding how an algorithm arrived at a given flag or prediction, to avoid black-box mystique influencing intel judgments.

Another AI worry is the generation of deepfake information. As AI can create utterly convincing fake images, video, or even entire fake persona with realistic social media histories, OSINT practitioners have to be on guard. The subcommittee seems attuned to this, given they invited a deepfake detection startup to brief them. The policy question becomes: should there be standards or approved tools for vetting open-source data integrity? Perhaps Congress will push the IC to adopt certified deepfake detection tools for any OSINT product (imagine a rule: no image from social media gets into an intel report without being scanned by deepfake detection algorithms). They might also fund R&D in this space as a national security priority.

Privacy and Civil Liberties: OSINT exists in a peculiar space regarding privacy. By definition, it uses “publicly available” information – which often means data that individuals have voluntarily posted or that is accessible in public records. However, in the age of big data, aggregating and analyzing public info at scale can feel like surveillance. For instance, an individual tweet or YouTube video is public, but if an intelligence agency compiles a million such items to profile a community or predict behavior, is that crossing a line? Civil liberties experts caution that government analysis of public data, especially on its own citizens, can chill free expression and blur the spirit of the Fourth Amendment (which protects against unreasonable search). The OSINT Subcommittee, by encouraging more open-source collection, might inadvertently encourage agencies to scoop up data on Americans under the banner of OSINT. True, the IC is generally foreign-focused by law, but many open sources (like social media) don’t neatly sort by nationality. A satellite image or foreign news site is one thing; a dataset of social media posts might include Americans’ communications.

Congress is aware of this tension. Notably, the debate around renewing FISA Section 702 (which allows surveillance of foreign communications) has expanded to discuss OSINT. Some argue OSINT can reduce the need for intrusive surveillance by providing information openly, thus preserving privacy – as one op-ed put it: “we need not sacrifice civil liberties… to benefit from OSINT.” The authors (former intel officials) contended that using open-source data actually helps protect privacy by illuminating threats without touching private communications. They urge that any reforms to spy laws (like 702) acknowledge the role of OSINT and avoid hobbling it. This perspective is echoed by others who see OSINT as a way to get necessary intel “with little scrutiny” under current law – which alarms some privacy advocates.

Thus, a brewing policy question: Should there be explicit legal definitions and limits for OSINT? Currently, if an intel agency wants to collect content from a U.S. person’s social media, is it allowed if that content is public? Typically yes – if you tweeted it publicly, the FBI or NSA can read it without a warrant. But if they use sophisticated data mining to draw conclusions about you, some argue that becomes “merging databases” in a way that might require oversight. The subcommittee will likely ensure agencies have guidelines for handling U.S. person data in OSINT. Perhaps they’ll reinforce that when scanning open info, the IC must implement privacy filters (e.g., anonymize U.S. person info unless it’s pertinent to a foreign intel mission). The NSIRA review in Canada explicitly is checking compliance with laws in DND’s OSINT activities, likely focusing on whether any Canadian law or directive (which forbid collecting on Canadians except under strict conditions) was skirted by calling something OSINT. The U.S. has similar prohibitions (CIA and NSA are limited in spying on Americans), but OSINT might slip through cracks if not codified, because one could argue “we’re not spying, just reading the news (or Twitter).”

To preempt backlash, the OSINT Subcommittee might work with civil liberties-oriented colleagues to craft policies that delineate acceptable OSINT from “inadvertent mass surveillance.” This could include legislative report language or directives that require, say, annual transparency reports on what kinds of data the IC is collecting via OSINT and how many U.S. person records get incidentally included. Considering the user’s question: might there be a legal definition of OSINT in the future with consequences for journalists and PIs? It’s conceivable. If Congress defines OSINT in statute (e.g., “information that is legally and ethically obtained from public sources, used by intelligence agencies”), it could either carve it out as fair game or impose conditions.

For example, imagine a law that says: “OSINT shall not include information for which a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy, or information acquired through deceit or violation of terms of service.” That could actually protect citizens but also might hamper investigators who sometimes create fake accounts to access forums (a gray area – is that OSINT or undercover work?). Alternatively, a formal definition could explicitly exclude journalistic activities to ensure reporters aren’t swept under intel regulations. One can envision paranoid scenarios: if OSINT becomes regulated, could a journalist’s open-source sleuthing on government wrongdoing be seen as “OSINT gathering” subject to some constraint? Unlikely in a democracy with First Amendment protections, but stranger things have happened when definitions creep.

More plausibly, legislation might target private investigators or data brokers who sell aggregated open info. Lawmakers could impose licensing (some states already license PIs) or require adherence to privacy standards – indirectly affecting journalists if they use the same data sources. For instance, if Congress banned scraping of certain websites by anyone other than authorized intel personnel, that could hamper open-source researchers outside government. However, given the pro-OSINT sentiment, any such move would likely aim to enable intel use while safeguarding civil liberties, rather than restrict journalistic OSINT. In fact, it’s more probable that Congress will attempt to legally distinguish between ethical OSINT vs. malicious use of open data (like doxxing or foreign propaganda). Perhaps new penalties for adversaries who misuse open info for harassment, while encouraging free investigation.

Surveillance vs. OSINT: There is a nuanced debate to be had on whether mass collection of public data constitutes surveillance. Privacy advocates argue that technology has changed the equation: what was once “public” (like walking in a park, captured maybe by a couple of eyes) is now recorded and analyzable by algorithm, thus practically erasing anonymity. If intel agencies start routinely ingesting feeds from public CCTV or license plate readers (some jurisdictions make that data public), they could track individuals en masse without ever “hacking” anything – it’s all open, but combined, it’s pervasive. The OSINT Subcommittee might have to engage with this issue, perhaps coordinating with the Judiciary or Homeland Security Committees on where lines should be drawn. Will Congress consider publicly posted personal info (like a Facebook profile, if set to public) as fair game for intel collection just as any foreign news article is? Or will they set higher standards when OSINT delves into personal data realms?

Future Legislation: It’s early, but one can imagine the subcommittee eventually proposing updates to foundational intelligence laws. The National Security Act and others don’t really mention OSINT. One idea floated by experts like Amy Zegart is a “Digital Intelligence” charter – not unlike how SIGINT has the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) governing it. A law or at least formal policy could define what agencies can (and can’t) do in gathering publicly available info. The goal would be to reassure the public that OSINT is not a loophole for domestic spying while empowering the IC to use modern tools. The subcommittee, balancing national security zeal with civil liberty concerns (note Ranking Member Houlahan’s comment about safeguarding Americans’ civil liberties while advancing security), is well placed to shape such guardrails.

Additionally, journalists and open-source researchers may see knock-on effects. If OSINT becomes a legal term, reporters might get lumped in or (ideally) carved out explicitly. Journalists currently benefit from the lack of regulation – they can scrape websites (within TOS limits), use satellite images, etc., without much restriction except general laws. If government starts licensing OSINT practitioners, journalists might worry about attempts to corral who can access what data. On the other hand, journalists might gain access to more government OSINT reports if the subcommittee’s transparency goals succeed. For example, if more unclassified OSINT-derived intelligence is released, reporters will have richer official info to incorporate or scrutinize.

Ethical Frameworks: Beyond privacy law, the mainstreaming of OSINT will prompt ethical frameworks akin to those in other disciplines. We may see, for instance, an OSINT Code of Ethics drawn up by professional bodies (the OSINT Foundation could lead this) that guides practitioners on issues like respecting human dignity (e.g., not gleefully sharing images of war dead from open sources), avoiding harm (not inadvertently outing dissidents by analyzing their social posts), etc. If these frameworks solidify, Congress might endorse them in policy. In short, OSINT’s ascent forces the question: just because we can know something openly, should we, and who decides? The forthcoming policy response will define the boundaries.

Is OSINT on track to become a central pillar of intelligence, equal to long-dominant disciplines like HUMINT (human espionage) or SIGINT (signals interception)? The actions of Congress and the IC suggest yes – at least, that’s the aspiration. This section peeks into the crystal ball, outlining short-term and long-term scenarios for the role of OSINT in the U.S. and allied intelligence architectures, and the broader evolution of the open-source ecosystem.

Short-Term (Next 1–2 years): In the immediate future, we can expect a flurry of activity to implement foundational improvements:

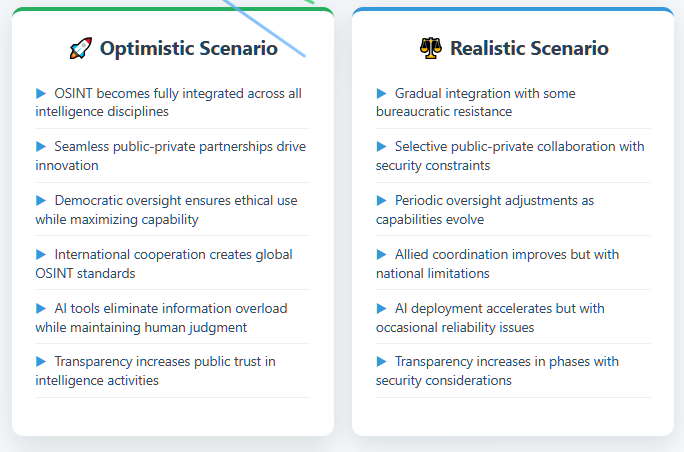

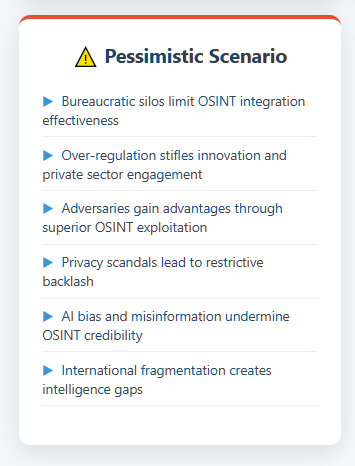

Long-Term (5–10 years and beyond): Looking further out, some plausible scenarios emerge:

Possible Challenges: Not all scenarios are rosy. There is the risk of over-reliance on OSINT leading to blind spots (if something isn’t openly available, analysts might mistakenly assume it doesn’t exist – a known cognitive bias). Also, intelligence bureaucracies might resist full integration (some old-schoolers might downplay OSINT quality, or agencies might jockey over who owns OSINT turf). The HPSCI subcommittee will need to keep pressure so that reforms don’t stagnate. Additionally, funding constraints could bite: shiny new OSINT programs might get initial funding but if budgets tighten, will they rob Peter (traditional collection) to pay Paul (OSINT)? Or vice versa? The optimal outcome is to find efficiencies (OSINT can reduce some expensive secret operations) and articulate that clearly to appropriators.

Nonetheless, the momentum suggests OSINT will not retreat. Too much has changed in the info environment for intelligence to revert to a cloistered model. As one analysis put it, OSINT’s rise is both familiar and an often-used bolstering argument for more investment, especially with the Ukraine conflict validating it. The likely trajectory is a continued climb to parity in importance.

To sum up: we are witnessing the mainstreaming of OSINT in national security. In the near term, that means building the bricks and mortar (or rather, the data centers and training classrooms) to support it. In the long term, it could transform how intelligence is done – making it more transparent, tech-driven, and inclusive of outside contributions. We might even say intelligence work is undergoing a quiet revolution: from the age of secrets to the age of openness (managed and analyzed for advantage). The strategic outlook is that those who master OSINT will have decision advantage in the 21st century’s competitions. The U.S. clearly intends to be among those masters, and the world will likely follow its lead, one way or another.

In light of the above analysis, we offer targeted recommendations for various stakeholders – policymakers, intelligence agencies, private OSINT firms, and journalists/NGOs – to navigate and shape the evolving OSINT landscape. Adopting these could help ensure that the institutionalization of open-source intelligence maximizes national security benefits while upholding democratic values.

For Policymakers & Oversight Bodies:

For Intelligence Agencies and the IC Leadership:

For Private OSINT Firms and Practitioners:

For Journalists, NGOs, and Civil Society OSINT Users:

In conclusion, these recommendations aim to channel the momentum behind OSINT’s rise into constructive, balanced progress. Open-source intelligence offers a historic opportunity to make intelligence more democratic (leveraging wide expertise), transparent, and responsive. If policymakers ensure proper oversight and ethical frameworks, agencies embrace integration and innovation, private sector provides trusted capabilities, and civil society remains vigilant, the result can be an intelligence enterprise that is not only more effective but also more aligned with democratic values. In the spirit of an “authoritarian voice” requested: the writing’s on the wall – or rather, in the open feeds. Those who learn to read it will rule the future, those who ignore it will be left in the dark. The United States and its allies must therefore proceed boldly yet wisely into this new OSINT-driven era of national security, setting a precedent that harnessing open information can indeed make us more secure, more free, and better informed all at once.