Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

The “Glomar response” – a refusal to confirm or deny the existence of records – has become a hallmark of government secrecy in national security and law enforcement contexts. Originating in the United States during the Cold War, this evasive formula allows agencies to answer information requests with a non-answer: “We can neither confirm nor deny.” The strategy is intended to avoid tipping off adversaries or revealing sensitive facts by the mere acknowledgment of records’ existence. In recent decades, the Glomar doctrine has not only been entrenched in U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) practice, but has also spread to other jurisdictions. In Canada, a similar “neither confirm nor deny” (NCND) logic appears in the federal Privacy Act and Access to Information Act, effectively a Canadian mutation of the Glomar response. This research examines the Glomar response’s legal origins in the U.S., its justification under FOIA exemptions, and the primary critiques leveled against it. It then analyzes how Canada has adopted and adapted the doctrine – particularly under Privacy Act section 16(2) – to uphold institutional secrecy for national security and investigative records, and asks whether this Canadian analogue stays within statutory limits (sections 12(1) and 16(2) of the Privacy Act) or risks abuse. Finally, a comparative and normative inquiry considers how Canada’s NCND regime stands relative to the U.S., UK, and Australia, what legal remedies (if any) exist to challenge such refusals, and the broader implications for democratic accountability, press freedom, and citizens’ rights. Throughout, the inquiry keeps in mind a critical question: What does it mean for a democracy when even the act of asking a question can be met with official silence?

Origins and Legal History: The term “Glomar response” was born from a 1970s FOIA case involving a covert CIA operation. In the Phillippi v. CIA case (D.C. Cir. 1976), journalist Harriet Ann Phillippi sought records about the CIA’s use of the Hughes Glomar Explorer – a specialized salvage ship built (under the guise of a Howard Hughes venture) to secretly recover a sunken Soviet submarine. The CIA’s reply to the FOIA request was unprecedented: it neither confirmed nor denied the existence of any records, arguing that if such records existed, acknowledging them would itself reveal classified information. The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, in Phillippi, recognized this refusal as a legitimate response in certain FOIA cases, effectively christening the “Glomar” response (after the vessel’s name) in American law. The court remanded the case for the CIA to justify its position, emphasizing that the agency must provide as much information as possible to demonstrate that even revealing the existence of records would damage national security. Thus, from the outset, the Glomar doctrine was a judicially crafted compromise – permitting evasive replies in FOIA matters, but only when a substantive response (even a confirmation or denial of records) would itself cause harm.

The Hughes Glomar Explorer – a CIA-commissioned salvage ship – gave its name to the “Glomar response” after the CIA refused to confirm or deny records about the vessel’s secret Cold War missionrcfp.org.

Under the U.S. FOIA (5 U.S.C. § 552), federal agencies are generally required to search for records and inform requesters whether any records were found, even if those records might ultimately be withheld under an exemption. The Glomar response is essentially an exception to this duty to confirm or deny. It is most often invoked pursuant to FOIA Exemption 1 (classified national defense or foreign policy information) or Exemption 7 (certain law enforcement records) when even admitting the existence or absence of records would disclose a fact that is itself classified or sensitive. For example, acknowledging that records exist about a still-covert operation or investigation could reveal that such an operation is underway; conversely, denying records exist could signal that a person or topic is not under investigation, information that could be just as useful to adversaries. U.S. courts have accepted that in these truly exceptional cases, agencies may refuse to confirm or deny the existence of records. However, agencies must justify the Glomar response in affidavits with sufficient detail to show that the very fact of records’ existence (or non-existence) is properly classified or protected by statute. The onus is on the agency to demonstrate that answering the question “records or no records” would harm an interest protected by a FOIA exemption (such as national security, confidential sources, etc.). If the agency meets this burden with plausible, logical reasons, courts will uphold the Glomar response. Otherwise, “the principles established in FOIA may outweigh claims to secrecy” and the agency could be compelled to respond more directly.

After Phillippi, the Glomar doctrine was applied in subsequent FOIA cases. Courts refined its use, insisting that Glomar be reserved for situations where the “secret of the secret” truly matters. One oft-cited rationale is that “the mere revealing of the existence or non-existence of information is in itself an act of disclosure” – e.g. telling a requester he is or isn’t the subject of an FBI or CIA file effectively discloses whether he has been investigated. Thus, U.S. agencies like the CIA, NSA, FBI, and others have routinely invoked Glomar to avoid confirming surveillance or investigatory files on individuals, and to protect information on intelligence operations, covert programs, or even certain sensitive policy deliberations.

The Glomar response’s archetypal use has been in national security and intelligence contexts – for instance, NSA FOIA requests about surveillance targets often meet Glomar replies, as do inquiries into CIA covert action programs. Over time, agencies also extended Glomar to law enforcement scenarios (e.g. the FBI responding to requests about whether someone is on a terrorist watchlist with a NCND answer). The Department of Justice has issued guidance on “Refusal to Confirm or Deny” in FOIA, sometimes called a “Glomarization” of responses, which instructs agencies on proper invocation – for example, in privacy-related FOIA requests concerning third parties, agencies may give a Glomar reply citing privacy exemptions if confirming the existence of records on a person would invade their personal privacy. (Notably, DOJ policy advises that a Glomar response for privacy reasons is not appropriate if the subject is deceased or has consented to disclosure, underscoring that NCND is meant to be a narrowly tailored tool.)

From its inception, the Glomar doctrine has been controversial. Transparency advocates, journalists, and some legal scholars argue that it undermines the spirit of FOIA and can be misused to shroud misconduct. One primary critique is that Glomar responses lack accountability – because the agency neither confirms nor denies anything, requesters are left in limbo with no information at all, and oversight is difficult. The requester cannot even be sure the agency conducted a search, and judicial review of Glomar is largely on trust (with courts relying on classified affidavits). As the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press noted in a 2024 analysis, Glomar has expanded from a Cold War relic to a “wide array of instances” today, yet agencies provide scant data on how often they use itrcfp.org. The RCFP had to FOIA every federal agency to compile statistics on Glomar usage, because annual FOIA reports do not explicitly track NCND responsesrcfp.org. Their study revealed that many agencies – not only intelligence bodies but others like the State Department, DEA, etc. – invoke Glomar, attaching it to various FOIA exemptions (though national security and law enforcement remain the most cited). The frequency and breadth of Glomar use raise concerns that it may be becoming a routine bureaucratic reflex rather than the rare exception it was meant to be.

Civil liberties groups point to specific cases as misapplications of Glomar. For example, in FOIA litigation over the U.S. government’s knowledge of the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, some agencies (the State Department) released certain records and even publicly denied having foreknowledge, while others (in the intelligence community) issued Glomar responses neither confirming nor denying any relevant record. In an amicus brief, a coalition of human rights organizations argued that these NCND responses were inconsistent and unjustified – effectively allowing agencies to “opt out” of FOIA obligations and evade the requirement for meaningful judicial review. They warned that an overly loose acceptance of Glomar lets agencies sidestep transparency mandates that Congress intended, especially on matters of high public interest like an extrajudicial killing. In their words, Glomar should be “permitted only in the narrowest of circumstances” because it is an extra-statutory doctrine grafted onto FOIA, not an explicit part of the law. Similar critiques have been voiced by the ACLU and media organizations in cases where, for instance, agencies issued Glomar responses regarding the use of torture, drone strike targeting, or bulk surveillance programs long after these topics were publicly known. In such scenarios, requesters argue that Glomar is being used less to protect legitimate secrets and more to avoid embarrassment or accountability.

Legal scholars have also examined the “creep” of the Glomar response beyond federal FOIA into state public records regimes and other areas of law. A study in Communication Law and Policy noted that since 2013, local and state agencies in the U.S. have occasionally adopted Glomar-like stances when responding to requests, even though those state laws often do not explicitly authorize NCND responses. This signals a potentially problematic expansion of a secrecy tool without clear legal grounding. Scholars emphasize that for Glomar to be acceptable, there must be integrity and consistency in its use – it should be applied in good faith, only when confirming/denying truly reveals protected information, and agencies should use it evenhandedly (i.e., not confirm in some situations and refuse in others just to suit their interests). Inconsistent use can undermine the rationale; for example, if an agency glomars one request but in another instance confirms the same type of record exists, it suggests arbitrariness.

In sum, the U.S. Glomar doctrine is a double-edged sword. It is grounded in legitimate concerns (national security, ongoing investigations, personal privacy) where silence can be protective. Courts have upheld it as a necessary, if unusual, mechanism under FOIA – provided the agency’s claim that “even admitting something would hurt” is logical and plausible. Yet the doctrine’s expansion and potential for abuse have drawn heavy criticism. The Glomar response, some argue, weaponizes ambiguity: it allows the government to erase even the question of whether it has information, making oversight and public debate exceedingly difficult. This tension between secrecy and transparency sets the stage for examining how a similar concept has taken root in Canada.

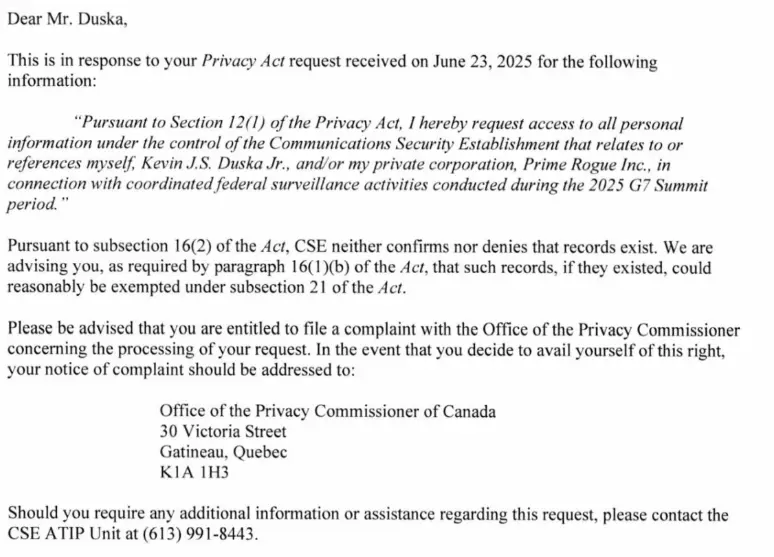

Statutory Basis in Canada: Canada’s federal law explicitly provides for a “neither confirm nor deny” style response in certain situations. Under the Privacy Act (R.S.C. 1985, c. P-21), which grants individuals the right of access to personal information about themselves held by government (section 12(1)), there is an exception carved out in section 16(2). Section 16(2) states that in responding to a Privacy Act request, a government institution may refuse to indicate whether any personal information exists, “in accordance with regulations”, if doing so could reveal information protected under specific exemptions. In plainer terms, an institution is not required to tell a requester whether or not it has personal information about them, if even that confirmation or denial would divulge something that should be kept secret. This is the Canadian incarnation of the Glomar response. Regulations under the Act (and related Treasury Board policies) clarify that when invoking s.16(2), the agency must also cite which exemption would apply to the records if they existed, and notify the requester of their right to complain to the Privacy Commissioner. In effect, section 16(2) allows the Canadian government to respond: “We neither confirm nor deny that we have any records about you, and if any such records exist, they would be exempt under [e.g. national security].” An example of this phrasing can be seen in a recent letter from the Communications Security Establishment (CSE):

“Pursuant to subsection 16(2) of the Act, CSE neither confirms nor denies that records exist. We are advising you, as required by paragraph 16(1)(b) of the Act, that such records, if they existed, could reasonably be exempted under subsection 21 of the Act.”

Here, CSE invoked s.16(2) to refuse even confirming the existence of records related to the requester (who had asked for any personal information CSE held about him in connection with surveillance at the 2025 G7 Summit) and pointed to s.21 as the hypothetical exemption (section 21 of the Privacy Act covers information related to international affairs, defense or security). This mirrors the U.S. Glomar template and is fully within the Canadian law’s allowance.

It’s important to note that Canada’s Access to Information Act (ATIA) – which governs general access to government records (like FOIA, but for non-personal information) – contains a similar provision. Under ATIA, section 10(2) provides that an institution may refuse to indicate whether any record exists, in cases where confirming or denying would itself reveal exempt information. This is essentially the ATIA equivalent of the Privacy Act’s s.16(2). For instance, when VICE News journalist Justin Ling filed an ATIA request to CSIS for financial records on a clandestine data-collection program, CSIS replied: “We neither confirm nor deny that the records you requested exist. We are, however, advising you, as required by paragraph 10(1)(b) of the Act, that such records, if they existed, could reasonably be expected to be exempted.”. CSIS then cited provisions of the ATIA related to ongoing investigations and “subversive or hostile activities” to justify this response. In other words, both of Canada’s access laws empower agencies with a Glomar-like refusal in situations involving sensitive information.

Why does Canadian law allow NCND responses? The rationale is akin to the American one: confirming or denying the mere existence of certain records can itself divulge information that ought to remain secret. Treasury Board Secretariat guidance explains that “Section 16(2) was designed to address situations in which the mere confirmation of a record’s existence (or non-existence) would reveal information that could be protected under the Act.” Specifically, it is “recommended that the application of section 16(2) be limited to circumstances where the confirmation or denial of the existence of a record would be injurious to Canada’s foreign relations, the defence of Canada, law enforcement activities, or the safety of individuals.” These correspond to the major exemptions in the Privacy Act (e.g. section 21 for international affairs/defence, section 22 for law enforcement and security, section 25 for safety of individuals). For example, if a person requests their file from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), simply telling them “Yes, we have a file on you” or “No, we have nothing” could, in the first case, tip them off that they are under investigation (potentially causing them to change behavior or flee), or in the second case, assure them they’re not being watched (information that could embolden wrongdoing). Similarly, if someone asked whether the government has records of them attending therapy via an Employee Assistance Program, a confirmation might invade their privacy, while a denial might indirectly confirm they did not – either answer reveals personal information. The policy is thus to allow neither answer in such cases.

Crucially, when a Canadian agency invokes s.16(2) of the Privacy Act, it must inform the requester which exemption would justify withholding the records if they existed. This prevents abuse by forcing the agency to anchor its refusal in a specific legal exemption and rationale. In the earlier CSE letter example, CSE cited “subsection 21” (the national defense/foreign affairs exemption), implying that if any responsive records existed (such as surveillance records on the requester), they would be classified as involving foreign relations or defense. Similarly, CSIS often cites section 21 (information relating to the efforts to detect, prevent, or suppress subversive or hostile activities) or paragraphs 22(1)(a)/(b) (law enforcement and investigative information) as the grounds that would apply. This practice is mandated by s.16(1)(b) of the Act (and ATIA s.10(1)(b) for Access requests), ensuring the requester isn’t left completely in the dark about the nature of the supposed exemption. In effect, the law says: you can refuse to say if there are records, but you must hint at the type of secret you’re protecting (e.g. “if we had records about you, they would relate to national security”). This provides a modicum of transparency around the refusal.

In practice, the NCND power in Canada is most frequently used by national security, intelligence, and law enforcement agencies – the ones most likely to hold very sensitive personal information and thus most likely to find s.16(2) applicable. Two agencies stand out: CSIS (the Canadian Security Intelligence Service) and CSE (Communications Security Establishment). CSIS has a long-standing policy of neither confirming nor denying the existence of records in its security intelligence dossiers. In fact, CSIS’s files on individuals are contained in what is called an “exempt information bank” (CSIS’s personal information bank CSIS PPU 045 is designated as exempt under Privacy Act regulations). The law (Privacy Act s.18(2)) permits an agency to refuse disclosure of any personal info in an exempt bank, and s.16(2) allows the agency to go further and refuse to even acknowledge any contents. Canadian courts have explicitly upheld CSIS’s “blanket policy” of not confirming or denying records in these exempt banks, recognizing that “the mere revealing of the existence or non-existence of information is in itself a disclosure: a disclosure that the requesting individual is or is not the subject of an investigation.” As the Federal Court of Appeal noted in Ruby v. Canada (Solicitor General), if CSIS were forced to say whether someone has a file, it would essentially reveal who is under surveillance and who isn’t – an outcome Parliament clearly intended to avoid by allowing NCND responses. Thus, a person requesting their CSIS file will invariably get a Glomar-type answer (unless perhaps the information is innocuous or already public). For example, journalist Carol Linnitt recounted that when she asked CSIS whether it had files on her or her news outlet, the agency replied that it could neither confirm nor deny having records, citing that CSIS is exempt from releasing such info as it relates to “detecting, preventing or suppressing subversive or hostile activities”. This language tracks the wording of the CSIS Act definition of “threats to the security of Canada” and the Privacy Act’s exemption for those activities. Linnitt found the response disconcerting – while she had no reason to think CSIS was spying on her environmental journalism, the refusal to say “no” was itself unsettling. It exemplifies how NCND can cast a shadow of uncertainty.

CSE, Canada’s signals intelligence and cybersecurity agency, likewise uses s.16(2) frequently. Being under the Department of National Defence, CSE often handles highly classified programs (e.g. foreign intelligence gathering, monitoring of communications) where virtually any personal information they hold could be sensitive. An indication of CSE’s use of NCND can be seen in its Annual Report to Parliament on the Privacy Act. In the 2022–2023 report, CSE noted that out of 22 Privacy Act requests closed that year, 11 requests (50%) were answered with a “neither confirm nor deny” response, a sharp increase from previous years. In fact, “Neither Confirm Nor Deny” was the disposition for half of all completed requests – by far the largest single category, dwarfing full disclosures (0%) and even partial disclosures. The report explains the rationale: “Section 16(2) indicates that institutions do not have to tell a requester whether personal information exists… it should be limited to circumstances where confirmation or denial would be injurious to Canada’s foreign relations, defence, law enforcement, or safety of individuals..” CSE’s heavy use in that year likely related to a surge of requests that, if answered normally, could ostensibly reveal whether certain people were subjects of intelligence operations (for instance, multiple individuals might have requested their info after a major event like the G7 Summit protests or a high-profile investigation, triggering NCND replies across the board). This data confirms that NCND is not a rarity at CSE – it’s practically standard in many cases.

Even outside the spy agencies, other federal bodies can and do use s.16(2) in niche situations. The RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police), for instance, might invoke it if a request touches on an active criminal investigation or sensitive policing technique. A civil liberties report noted that police in Canada maintained an absurd “neither confirm nor deny” stance for years regarding their use of Stingray cell phone interceptors, even as evidence mounted that they had and used these devices. While that stance was often taken in media inquiries or court, it aligns with the same logic – confirming use of a surveillance technology (or confirming records of its use) was seen as harmful to investigative effectiveness. Similarly, if someone suspected they were under a police investigation and made an access request, the RCMP could refuse to confirm or deny records citing law enforcement exemptions (Privacy Act s.22) so as not to tip off the target.

The pressing question is whether Canadian institutions overuse s.16(2) – employing Glomar-like responses beyond the narrow purpose intended. Critics worry that the neither-confirm-nor-deny clause could become a catch-all shield to deflect scrutiny of programs like bulk data collection, metadata surveillance, or profiling of activists. For example, after revelations in 2016 that CSIS had been secretly collecting metadata on Canadians (retaining incidental data illegally), one might expect affected individuals to request their information. CSIS could simply NCND every such request, burying the extent of that program’s reach. Privacy advocates have cautioned that while it’s fair for CSIS to withhold genuinely sensitive investigatory material, “they shouldn’t use this as a blanket excuse to refuse to release information.” Vincent Gogolek of the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association pointed out that under an overly broad interpretation, “there really aren’t any ‘citizens above suspicion’” in the eyes of CSIS – because no one can ever get confirmation that they are not in the files. This speaks to a potentially corrosive effect: if NCND is reflexively applied, everyone lives under a cloud of possible surveillance with no transparency.

That said, there are some checks and balances. The Privacy Commissioner of Canada provides independent oversight: an individual who receives an NCND response can file a complaint with the Commissioner’s office (OPC). The OPC will then confidentially investigate – it can ask the agency to see the records (or confirm their existence) under strict secrecy and assess whether the refusal was properly applied. In the case of Ms. Chin v. Canada (Attorney General), Chin believed she was a victim of clandestine harassment and asked CSIS for any records on her. CSIS issued a Glomar response under s.16(2), citing s.21 (national security) and s.22 (law enforcement) as the applicable exemptions. Chin complained to the OPC, but the Commissioner found the complaint “not well-founded,” essentially agreeing that CSIS was entitled not to confirm or deny anythingcanada.ca. Chin then went to Federal Court seeking a review. In 2022, the Federal Court (Chin v. Canada, 2022 FC 464) upheld CSIS’s response as reasonable and within the law. The court acknowledged Chin’s mental distress (noting that strict NCND policies can “exacerbate mental health challenges” for individuals who fear they are surveilled)canada.ca, but it concluded that the law was correctly applied and that her Charter rights were not violated by the mere refusal to confirm recordscanada.ca. The Chin case highlights both the human impact of Glomar (the applicant felt tormented by the non-answer) and the legal reality that the courts view such responses as a permissible tool, even a “necessary evil” in national security matters. Indeed, the court in Chin cited prior cases like Russell (2019) and Hutton (2021) that grappled with similar issues, indicating a pattern of upholding s.16(2) even while recognizing its harshnesscanada.ca.

Another check is internal policy guidance. The Treasury Board’s ATIP Implementation Notice 2024-01 counsels institutions to use NCND sparingly. It gives a scenario where a request for Employee Assistance Program records might be answered with NCND because confirming the existence of records of an employee’s counseling sessions would itself reveal sensitive personal infocanada.ca. The guidance implies NCND is more likely justified for very specific and sensitive requests, and it reminds institutions that they may invoke it, but are “not required” to do so in every casecanada.ca. In practice, however, agencies tend to err on the side of secrecy – especially those whose culture and mandate emphasize confidentiality (CSIS, CSE, military, etc.). Critics argue that over-classification and over-secrecy in Canada’s security apparatus lead to overuse of provisions like s.16(2). For instance, if a person requests something relatively benign – say, “all information about me in government records” – most departments would either find none or release what they have. But a security agency might default to NCND even if all they have is a single benign mention, just because policy says to never confirm records from certain databases. This could be seen as stretching the law beyond its purpose. The wording of s.16(2) doesn’t compel NCND; it says the institution may refuse to indicate if information exists. It’s discretionary, to be applied when needed to protect an exempted interest. If institutions start using it as a blanket rule in whole categories of requests, that edges into abuse of the discretion.

Internal Limits and Commissioner’s Role: The Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) has, to date, not publicly chastised agencies for misuse of s.16(2). In fact, OPC decisions (which are usually private to the parties unless they go to court) in cases like Chin and others have tended to side with the agencies if the conditions of the law are metcanada.ca. The OPC’s remit is to ensure the law is followed, and s.16(2) is part of the law. There may be instances where the OPC can mediate – for example, if an agency invoked NCND incorrectly (say, no real exempted interest at stake), the OPC could recommend the agency at least confirm or deny. Also, not all NCND responses are final – sometimes an agency might initially give a Glomar response but later, if the sensitivity dissipates (e.g., an investigation ends), they might confirm records existed. However, such reversals are rare and would likely only come out through persistence or political pressure.

In terms of formal guidelines, the Treasury Board Personal Information Request Manual likely elaborates on s.16(2) usage (the TBS notice references this manual). Additionally, Info Source bulletin and Federal Court jurisprudence (summarized by TBS in bulletin 46A) reiterate that “Subsection 16(2) … permits a government institution not to confirm whether personal information exists within an exempt information bank”canada.ca. They cite that the Federal Court of Appeal has confirmed CSIS’s right to a blanket NCND policy for its investigation recordscanada.ca. So, institutionally and legally, the NCND concept is well-entrenched in Canada’s access regime for sensitive information.

In summary, Canada’s Privacy Act does authorize a Glomar-equivalent response (s.16(2)), and it has been actively invoked by agencies like CSIS and CSE in the expected domains of national security, defense, law enforcement, and also to protect individuals’ sensitive privacy (in niche cases). The use of this provision has increased in recent years (at least judging by CSE’s stats)cse-cst.gc.ca, raising concerns about overuse. While designed for narrow circumstances, NCND in Canada arguably has become a standard operating procedure for intelligence files – potentially insulating broad surveillance programs or data troves from any public awareness. The key question is whether this use respects the statutory limits. The law’s limit is essentially that an exemption must reasonably apply if records exist. As long as agencies can point to a plausible exemption (which, given the broad language of national security and law enforcement exemptions, they usually can), they are within their legal rights. Ethically and democratically, however, the question of overuse lingers – especially if NCND is invoked in situations that do not truly pose a grave harm, but rather to avoid inconvenience or embarrassment. The next section will explore how this Canadian approach compares with other countries and the avenues (or lack thereof) to challenge it, alongside implications for rights and accountability.

Canadian security and intelligence agencies frequently invoke a “neither confirm nor deny” response to information requests. Above: The headquarters of CSIS in Ottawa. Provisions like Privacy Act s.16(2) allow CSIS to refuse confirming whether an individual is mentioned in its records, on the basis that merely revealing someone is (or isn’t) under investigation would itself compromise national securitycanada.cacanada.ca.

Comparative Secrecy Doctrines (US, UK, Australia): Canada’s NCND regime is broadly in line with practices in other Western democracies, though the legal mechanisms differ. In the United States, as discussed, the Glomar response is a judicial doctrine under FOIA, not explicitly written into the statute but universally recognized through case lawen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. U.S. agencies invoke it under FOIA exemptions (especially for classified info and ongoing investigations) and must defend it in court if challenged. In the United Kingdom, the Freedom of Information Act 2000 explicitly provides that the government may issue a refusal “neither confirming nor denying” the existence of requested information when certain exemptions apply. For instance, FOIA section 1(1)(a) in the UK establishes a general duty to confirm or deny holding information, but this is disapplied if an exemption’s specific NCND provision is engaged (many of the UK’s exemptions – national security, law enforcement, personal data, etc. – contain clauses allowing NCND). The UK Information Commissioner’s Office publishes guidance on using NCND, making clear it should only be used when revealing the mere existence of information would itself harm the interest protected by an exemptionassets.publishing.service.gov.uk. For example, UK agencies have often neither confirmed nor denied requests about intelligence agency activities or whether someone is on a terror watchlist, similar to Canadian and U.S. practice. In Australia, the federal Freedom of Information Act 1982 includes at section 25 a provision that an agency may give a response stating that “neither confirming nor denying the existence of documents”, in cases where certain exemption claims could apply (such as national security, law enforcement, or personal privacy)oaic.gov.au. The Australian Office of the Information Commissioner provides sample language for such responses and notes they are for “certain narrow circumstances.”oaic.gov.au State-level legislation (e.g. in Queensland or Victoria) also has similar NCND clauses for their information access lawsovic.vic.gov.auovic.vic.gov.au. Meanwhile, other countries like New Zealand and many European nations have analogous concepts embedded in their Right to Information or data protection laws, particularly to protect security and defense records.

So, Canada is not an outlier in having a Glomar-like mechanism; rather, it is part of a global pattern in which democracies carve out narrow refusal-to-confirm options in transparency regimes to safeguard vital interests. All these systems wrestle with the same balance: transparency as default vs. secrecy when necessary. The Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (Tshwane Principles), a set of non-binding international guidelines, acknowledge that certain information (like identities of confidential informants, ongoing covert operations, etc.) may justify neither confirming nor denying in response to public requestshrw.orghrw.org. However, these principles also urge that such responses be limited and subject to oversight.

Remedies and Oversight in Canada: What can an individual do if they receive a Glomar response under the Privacy Act’s s.16(2)? The legal pathway is twofold: an OPC complaint followed by potential judicial review. The Privacy Commissioner’s investigation is the first stop; as we saw, the OPC can examine the agency’s reasoning (often behind closed doors) and attempt mediation or make a recommendation. If the requester is unsatisfied (or if the OPC finds the complaint well-founded and the institution still refuses to change course), the requester can apply to the Federal Court under section 41 of the Privacy Act to review the denial of accesscanada.ca. In Federal Court, the onus is on the government to prove that the refusal was justified under the Act (Privacy Act s.47 places the burden of proof on the government)canada.cacanada.ca. However, the court’s review process in national security cases often happens in camera and ex parte – meaning the judge will see the secret evidence (such as whether records exist and why confirming would harm security) without the requester or public present, much like FOIA cases in the U.S. This limits the requester’s ability to rebut the government’s claims, and they must trust the court’s assessment. Canadian courts have generally been deferential to the government on s.16(2) issues, especially post-Vavilov (the 2019 Supreme Court decision on standard of review). In Chin, the Federal Court applied a reasonableness standard to both CSIS’s interpretation of the law and its exercise of discretion, intervening only if the decision was not justified or intelligiblecanada.cacanada.ca. It found CSIS’s refusal met the bar of reasonablenesscanada.ca. Similarly, earlier cases like Ruby v. Canada (which went to the Supreme Court in 2002) set the tone: Mr. Ruby, a lawyer who sought his own security file, was denied access (not exactly via Glomar, but via exemptions and a special certificate), and the Supreme Court upheld the secrecy procedures, emphasizing deference to national security and the statutory scheme (which allowed in camera, ex parte review)canada.ca.

Thus, as a practical matter, legal remedies exist on paper but are limited in outcome. There have been no known successful challenges where a court forced an agency to break a neither-confirm-nor-deny stance under the Privacy Act. At best, a court might ensure the agency was properly applying the law (for instance, if an agency tried to use s.16(2) without pointing to a valid exemption, the court could overturn that decision – but such a scenario is unlikely, since agencies will always cite an exemption). The Office of the Information Commissioner (OIC) plays a similar role for Access to Information Act requests invoking ATIA s.10(2) – requesters can complain to the OIC if they get an NCND under the access law. The OIC’s published guidance notes that under ATIA “subsection 10(2) allows institutions to refuse to confirm whether records exist” provided confirming existence would itself reveal exempt informationoic-ci.gc.ca. Institutions must show both that confirming/denying would disclose exempt info and that, if records exist, they could be exempt under specific provisionsoic-ci.gc.ca. Only if both conditions hold can they use NCND. The Information Commissioner and ultimately the Federal Court can examine those conditions. In practice, much like the OPC, the OIC rarely orders disclosure in such cases, since doing so would contradict the very premise of the exemption.

One conceivable remedy – outside the Privacy Act process – is political or public pressure. If an issue is of high public interest, sometimes the government may choose to disclose information voluntarily rather than stick to NCND. For example, after years of NCND about Stingray devices, the RCMP eventually admitted use of them in a Parliamentary committee hearing, due in part to media and legal pressure. However, that’s an exception; by default, agencies won’t flinch from the NCND stance unless compelled.

Charter of Rights and Freedoms Considerations: Could the use (or overuse) of s.16(2) ever violate Canadians’ Charter rights – notably section 7 (right to life, liberty, and security of the person) or section 8 (right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure)? This is a complex issue. On its face, a refusal to disclose information is a matter of access to information law, not directly a Charter search or seizure. Section 8 is about privacy against state intrusion – secret surveillance or data collection might violate s.8 if done without lawful authority or reasonable grounds. But s.8 doesn’t guarantee one a right to know whether they were surveilled; it only can be invoked if a person can prove in court that an unreasonable search occurred. The fact that the government neither confirms nor denies holding your data doesn’t in itself constitute a search or seizure – it’s a withholding of information. Therefore, courts have not treated NCND responses as engaging section 8. If anything, to pursue a section 8 remedy, a person would have to somehow demonstrate that surveillance took place and was unlawful – a Catch-22 if you can’t even confirm it happened. Some have suggested that if NCND is used to conceal an unlawful surveillance program that affected many people, perhaps a Charter challenge could be launched to force an investigation or disclosure in the public interest. But generally, Charter litigation requires a concrete infringement; the ambiguity of NCND doesn’t easily fit a Charter claim.

Section 7 (life, liberty, security of the person) could be argued in a case like Chin’s – she effectively argued that her psychological security was harmed by being left unprotected and in the dark. However, to show a s.7 violation, one must prove the state deprived them of security of the person in a manner not in accordance with fundamental justice. The Federal Court in Chin implicitly found no such deprivation: CSIS did nothing to her except refuse information, which the law permits. Unless one could show that NCND responses are part of a justice system procedure that is fundamentally unfair (for example, if someone’s liberty was at stake in a legal proceeding and the government refused to confirm evidence – a very different context), section 7 is unlikely to apply.

One hypothetical: if the government’s use of NCND were so excessive that it concealed gross violations of rights (e.g., say a program of surveillance that led to Charter breaches, and NCND thwarted any accountability), one might argue this offends fundamental principles of justice. But that’s more of a political argument than a legal one absent a test case. Canadian courts have been generally unreceptive to broad Charter arguments in the access-to-information sphere, treating access rights as creatures of statute, not constitutional rights. The Supreme Court in Ontario (Public Safety) v. Criminal Lawyers’ Association (2010) did recognize a limited constitutional right to information in some contexts (related to expression under Charter s.2(b)), but that’s outside our scope and didn’t touch on NCND.

In short, while one can theorize about Charter challenges, so far the neither-confirm-nor-deny regime has survived legal scrutiny. Courts consider the closed-door, ex parte review process as sufficient safeguard (as per Ruby and later cases), and they have not found that refusing to confirm or deny records violates Charter rights, especially given the importance attributed to national security and public safety exceptions.

Implications for Journalism and Public Oversight: The NCND tactic has significant ramifications for journalists, researchers, and citizens attempting to hold institutions accountable. Investigative journalism relies heavily on access to information laws; a Glomar response is a brick wall. As Carol Linnitt wrote, these “non-denial denials” are “par for the course when dealing with intelligence services”thenarwhal.ca, but they are nonetheless vexing. A journalist who suspects, for instance, that a domestic spy agency monitored environmental protesters or tracked social media may file an ATIP request. Getting back “neither confirm nor deny” shuts down that line of inquiry. It also means the journalist cannot report definitively whether such surveillance occurred – the story becomes one of process (“Agency X refuses to say if it spied on Y”) rather than substance. In some cases, the very refusal can itself be news (as in Vice and Narwhal articles highlighting CSIS’s use of NCND responsesthenarwhal.cavice.com), but it often leaves the public with more questions. It also can discourage journalists from even trying, knowing that certain agencies will simply Glomar-out any request touching their core operations. This limits the effectiveness of adversarial OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) gathering through FOI requests. OSINT researchers who use public records to piece together government activities find NCND responses to be dead ends that provide no usable data point (except the inference that if records exist, they are sensitive).

For civil society and watchdog NGOs, NCND can be equally frustrating. Organizations like the BC Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA) or Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE) may want to uncover the extent of surveillance of activists, or whether intelligence agencies are profiling certain communities. Blanket NCND responses prevent them from even quantifying the issue (e.g., “How many Canadians are listed in database X?” could be met with NCND, whereas a “no records” would reassure or a large number would alarm). Thus, NCND stymies public debate by withholding even the most basic facts that an issue exists.

Parliamentary and Court Oversight are meant to fill this gap in theory – Canada has specialized review bodies like the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) and the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP) that have broad access behind the scenes to classified info. These bodies could verify whether agencies are properly using their NCND power and not abusing rights. However, their findings often remain classified or high-level in public reports. For example, NSIRA could examine CSIS’s metadata collection program (as it did) and report that CSIS illegally retained data, but individuals affected might still never know if their data was in there due to NCND at the front-end. Meanwhile, even Parliament can face the NCND stonewall. The BCCLA noted an instance where CSIS would not even confirm to a parliamentary committee whether it believed a warrant was needed to use cell-site simulators (Stingrays) – effectively refusing Parliament a straight answer on a point of law and policybccla.org. This “shocking” lack of candor, as the BCCLA termed it, underscores how deeply ingrained the neither-confirm-nor-deny reflex is in the security establishment – to the point of evading legislative scrutinybccla.org.

Democratic Values and “Asking Becomes Classified”: The broader democratic implication is that the Glomar response, if overused, can erode trust and accountability. In a democracy, citizens ought to have the ability to ask their government “Do you have information about X?” and get an answer, even if that answer is, “Yes, but we can’t disclose it.” The NCND response is a step further back: it refuses to even engage on the question. As a result, public discourse may be warped by uncertainty. People like Ms. Chin, who believe they are surveilled, receive no closure – potentially leaving them feeling helpless or paranoid, which can be a genuine personal harm. More broadly, if communities (say, environmental activists or minority groups) suspect they are being monitored, an inability to ever confirm or refute those suspicions can create a chill on civic engagement. Individuals might refrain from legitimate activism or speech due to fear of surveillance, a fear that can neither be allayed nor confirmed. Such “erasure of epistemological accountability” – where the state doesn’t even acknowledge what it knows – can be corrosive to the democratic principle that government is ultimately answerable to the people. Transparency advocates argue that while secrecy is sometimes necessary, it must be narrowly applied and offset by robust independent oversight; otherwise, NCND becomes a “discursive weapon” that authorities wield to unilaterally control the narrative and shield themselves from critique.

On the other hand, one must also acknowledge the state’s perspective: confirming or denying certain information really can cause harm. If a criminal suspects he’s under investigation because the police had to confirm records to him, he might destroy evidence or intimidate witnessesen.wikipedia.org. If a terrorist group learns through an innocuous FOI that an intelligence service has no file on a certain route or method, they might exploit that blind spot. These are scenarios law and policy-makers have in mind when allowing NCND. The challenge is ensuring this tool is not stretched beyond those scenarios. For democratic legitimacy, the use of NCND must be accompanied by a commitment that it’s exceptional and justifiable.

In Canada, some reforms have been suggested: for instance, giving the Privacy Commissioner (or NSIRA) the power to review a random sample of NCND responses to ensure they were truly necessary, and report on the frequency of use. Another idea is requiring a time-limit or re-evaluation – perhaps an NCND could “sunset” after a number of years if the sensitivity passes (e.g., historical files might eventually be acknowledged). Currently, there is no formal sunset; many Glomar responses can essentially last indefinitely (though one can re-request later to test if the answer changes).

In conclusion, Canada’s adoption of the Glomar response through section 16(2) of the Privacy Act shows the globalization of this doctrine of secrecy. Legally, Canada has grafted the concept into statute, arguably with clearer parameters than the original U.S. case law. Doctrinally, it serves the same theory: protecting the fact of surveillance or sensitive records from disclosure. Yet its expansion in practice – as evidenced by half of CSE’s Privacy Act requests being answered with NCND in a recent yearcse-cst.gc.ca – raises red flags. Is it legally sustainable? Yes, the courts have upheld it. Is it ethically defensible? Only to the extent it’s genuinely used to prevent real harm, not to cover up inconvenient truths. Is it democratically corrosive? It can be, if it becomes a routine shield thwarting citizens’ right to know what their government is up to. The phrase “neither confirm nor deny” was once an extraordinary response associated with spies and submarines; it is now a part of Canadian bureaucratic lexicon. The onus is on oversight bodies and ultimately Parliament to ensure that this powerful form of silence is confined to the narrow purposes for which it was intended – and that our democracy retains the ability to ask questions without the answer itself being classified.

Sources:

Fascinating breakdown of how the Glomar response has evolved within the Canadian context under the Privacy Act. It’s interesting—and a bit alarming—to see how a tool originally designed for national security secrecy is being adapted to shield bureaucratic processes from scrutiny. This really raises questions about where transparency ends and institutional self-protection begins.

I swear you probably have some dumb CSE bureaucrats monitoring the wax blockchain now. Congratulations! This is your life’s work.

[…] This is our second Glomar in a week. That alone suggests institutional discomfort. […]

[…] Maple Leaks 001: FINTRAC and Jeffrey Epstein – a Canadian GLOMAR RESPONSE […]

[…] That’s not even to mention the two Glomar Responses that I received from Communications Securi… […]

The honour of a GLOMAR – you must be incredibly proud

ok your GLOMAR NFT is hilarious.