Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

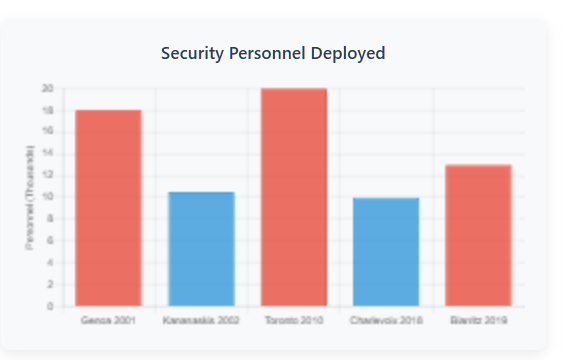

International summits routinely invite massive protests – and equally massive, often preemptive security responses. Notorious examples include Genoa (2001) and Toronto (2010), where protest-related violence and police excesses drew global scrutiny. This report examines major summit incidents, revealing recurring failures: over-militarized policing, false threat narratives, draconian restrictions on assembly, intrusive surveillance, and scant accountability. The case studies below (G8 Genoa 2001, G8 Kananaskis 2002, G20 Toronto 2010, G7 Charlevoix 2018, and G7 Biarritz 2019) detail on-the-ground tactics, intelligence missteps, rights abuses, and legal fallout. We conclude with a risk analysis for the forthcoming G7 (Kananaskis 2025), highlighting new surveillance tools and evolving protest dynamics.

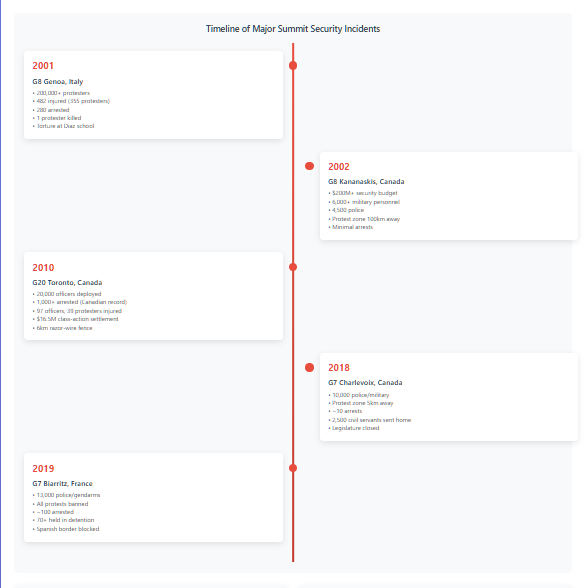

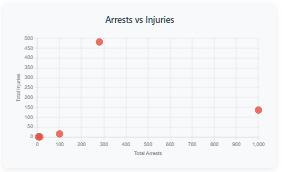

From July 19–21, 2001, Italy’s northern port city became a “fortress under siege” as 200,000+ demonstrators massed. On 20 July, a street clash turned deadly when 23‑year-old Carlo Giuliani was shot by police after allegedly approaching an armored car with a fire extinguisher. That evening, police carried out a notorious raid on the Diaz school, where hundreds of activists (many sleeping) were beaten and injured. Officers fired live rounds and rubber bullets into crowds, deployed water cannons and tear gas, and formed “snatch squads” to grab protesters. In all, 482 people (355 protesters, 19 journalists, 108 police) were injured and 280 arrested.

Pre-summit briefings emphasized terrorism fears rather than legitimate dissent. Italian and allied security services spread rumors (e.g. an alleged al-Qaeda plot to assassinate President Bush) to justify draconian measures. Protesters – organized under the Genova Social Forum – posed no such threat, but police treated them as a “paramilitary” enemy. Thousands of activists were pre-identified: Italy reinstated border controls and turned away 2,093 foreigners at airports and ports. Notably, many arrested (charged with “criminal association aimed at destruction”) were peaceful global justice activists. Post-event inquiries found that police had fabricated evidence (planting Molotov cocktails) and vastly overstated the danger, effectively criminalizing dissent.

Genoa saw sweeping rights abuses. Peaceful demonstrators were batoned, shot at, and detained en masse without due process. Within hours of the Diaz raid, arrestees were herded into the Bolzaneto temporary jail, where detainees reported torture, beatings, and humiliation (some raped with truncheons). By 2008, prosecutors acknowledged that many of the 40 prisoners at Diaz “suffered … inhuman and degrading treatment.” In 2015 the European Court of Human Rights unanimously held that the Diaz beating amounted to “torture” and that Italy’s laws were inadequate to prosecute it. Other violations included denial of counsel: protest leaders deported at Italian airports were held in a “sterile zone” and told they had no right to a lawyer. Journalists (19 injured) and many local residents were also caught in indiscriminate police charges.

Domestic and international scrutiny followed, but few officers faced real consequences. Italian courts eventually convicted a handful of policemen: in 2008, 15 officers were found guilty for the Diaz and Bolzaneto brutality (sentenced 5 months–5 years). However, most defendants were acquitted or escaped punishment on appeal. The government launched inquiries – three police investigations and a parliamentary committee – and removed several senior commanders, but no high-ranking official was ever jailed. Internationally, Italy was condemned by the ECtHR (Cestaro v. Italy, 2015) for failing to punish torturers. In short, Genoa exposed a culture of impunity: a parliamentary report called public order policing “a new nadir.” while victims and human-rights groups complained that justice was slow or incomplete.

In stark contrast to Genoa, the Kananaskis summit (June 26–27, 2002) was staged in a remote mountain resort two hours west of Calgary. Security forces declared the site a “fortress”: CF‑18 jets and tank patrols guarded the skies; multiple ground-to-air missile batteries ringed the perimeter; 6.5 km of roads were closed with checkpoints, 12-ft barbed-wire fences were erected, and even forest trails were off-limits. Over $200 million was spent on security: 6,000+ Canadian Armed Forces (including anti-terror units) and 4,500 police sealed off Kananaskis Village. One illustrative event: on June 26, a caravan of activists (cars and campers) attempted to reach the summit, only to be halted by 25 police/military checkpoints. Only a handful of protesters (e.g. postal workers) succeeded in delivering G8 “letters” after long negotiations.

Former Prime Minister Chrétien openly chose Kananaskis to avoid protesters, not because of any concrete terror plot. The government had contemplated invoking a new anti-terrorism law to declare the area a “military security zone,” but publicly the aim was to keep dissidents out of sight. In practice, intelligence assets focused on surveillance: undercover agents monitored Calgary and Ottawa, and live heat-seeking sensors scanned the woods. Authorities downplayed any genuine protest threat. One RCMP planner candidly explained that “we plan for the worst-case scenario” and then reactively dialed security up or down – indicating a bias toward overkill which reflects RCMP and Public Safety Canada culture to this very day.

Virtually no protests were allowed near Kananaskis. The nearest designated “protest zone” was Calgary, 100 km away. In Calgary itself, police presence was overwhelming: marks of a “martial-law” atmosphere were noted in local press. Highways into the region were locked down – the only road through Kananaskis County was barricaded with mandatory vehicle searches and escorted convoys. Civil servants in Edmonton and Calgary were sent home, Alberta schools canceled classes, and thousands of law-abiding citizens simply steered clear of the area. The effect was to effectively nullify the right of assembly: no large gatherings formed in Kananaskis, and peaceful demonstration devolved into small, isolated events miles from the summit site.

With little actual conflict, legal fallout was muted. There were no high-profile police abuse cases or trials following Kananaskis. Critics (e.g. civil-liberties groups) denounced the unprecedented “military-security” posture, but no court challenges succeeded. Inquiries into Kananaskis security were limited to government reports; no domestic or international body formally faulted Canada after the fact. In effect, the outcome was a “success” for the authorities (no serious riots), albeit at the cost of virtually suspending protest rights. Long-term, Kananaskis set a template for “summits in the wilderness” – a model repeated at Charlevoix and other G7 venues.

Over June 26–28, 2010, Toronto’s downtown was sealed off for the G20 and G8 summits. Up to 20,000 officers and soldiers were deployed around Parliament and the convention center. In the week before the summit, 6 km of fences topped with razor wire encircled the “red zone.” On the streets, police used militarized tactics: snatch squads running into crowds, nightstick and baton charges, pepper spray, and volleys of tear gas and rubber/plastic bullets against even largely peaceful marchers. Armored tactical vehicles (“TAVIS” APCs) patrolled city streets. A makeshift detention center was erected on a closed film-studio lot. By June 27, 600+ protesters had been arrested, and police reported 97 officers injured (39 protesters injured). In total more than 1,000 people were detained (the largest mass-arrest in Canadian history).

Months before, the RCMP and Integrated Security Unit aggressively monitored activists. RCMP’s Joint Intelligence Group admitted infiltrating protest networks across Canada (Vancouver, Toronto, Ottawa, Montréal) in “one of the largest such operations” ever. Intelligence briefings stressed potential violence (often citing black-clad “black bloc” rioters), arguably overstating the danger posed by mostly peaceful demonstrators. In practice, any hint of dissent was treated as subversion: police drafted contingency plans for a “riots” scenario, even as major planned marches were authorized by courts. Early on June 26, police unilaterally set up an “inside fence” in Queen’s Park to block a legally permitted rally (the “Die-in”), later rescinded by courts. In short, threat assessment was skewed toward worst-case confrontation, fueling a preventive crackdown.

Civil rights groups documented widespread Charter breaches. Arbitrary mass arrests and indiscriminate charges (often “criminal organization” or conspiracy) ensnared many non-violent protesters. The police-created “free speech zone” concept meant that most demos were either blocked or corralled far from the summit (often at Metro Toronto Convention Centre parking lots). Unannounced warrantless searches became commonplace; one landmark case (Luke Stewart’s) later found Toronto police had no authority to perform blanket bag searches at marches. Racial profiling was reported: a disproportionate number of young Black men were strip-searched or arrested near Queen’s Park. Journalists covering the protests were shoved and pepper-sprayed. Notably, police even fired tear gas into a peaceful crowd of several hundred at Queen’s Park on June 27 for attempting a clothing-optional demonstration – an act widely condemned as gratuitous.

Toronto’s clampdown prompted a flood of lawsuits and inquiries. A class-action lawsuit on behalf of arrestees was approved to proceed by Canada’s Supreme Court (2016) and ultimately settled for CAD $16.5 million in 2020. Settlements ranged from $5,000 to $24,700 per individual. In 2020, courts emphatically ruled that mass police searches of protesters were unlawful. However, no officers were ever criminally convicted; internal police investigations largely cleared the use-of-force (though civilian complaints remained open for years). The G20 report by the Ontario Civilian Police Commission later chastised the TPS/RCMP joint command for overreach, and the Ontario Ombudsman launched an inquiry. The episode left a legacy of public distrust and legal limits on protest rights: Ontario’s protest legislation was overhauled in part to codify assembly protections.

The Charlevoix summit (June 8–9, 2018) at Le Manoir Richelieu resort, Québec, was ringed by 10,000 police and military personnel. By official plan, all demonstrations had to occur in a small “free speech” parking-lot zone 5 km from the summit. In practice, few large protests materialized: activist groups instead concentrated in Quebec City (140 km away). On June 7, a small convoy of masked protesters briefly blocked Route 138 (the road between Quebec City and La Malbaie); police quickly dispersed the barricade and arrested one man. Over the two summit days, roughly 10 protesters were arrested. These incidents were minor compared to previous summits, reflecting the largely peaceful nature of the anti-G7 movement and the remoteness of Charlevoix.

Quebec authorities embraced a precautionary stance. As Minister Castaner warned, they expected “violent groups” at the summit and geared up accordingly. Police intelligence reportedly scanned social media and intercepted chatter of “counter-summit” plans. Before the meeting, the RCMP and provincial police publicly cautioned citizens (“don’t daydream about” illegal acts) in notices, signaling pre-emptive intimidation. Notably, civil society groups anticipated trouble: the Council of Canadians opposed the RCMP’s intention to confine protests to the free-speech zone, warning that policing should not rest on “broad state powers” unseen in law. In the event, authorities’ risk assessment proved alarmist: no large-scale riots occurred. Protest activity was largely peaceful marches and sit-ins, often well away from the resort.

Charlevoix’s security legacy centers on restrictions more than violence. The Quebec government closed the legislature, sent 2,500 civil servants home, and ordered downtown businesses to board up – measures akin to martial law. An unelected curfew in Quebec City was reported (though not formally enacted). Access to certain highways and scenic roads was temporarily prohibited. Tolerated demonstrations were very limited: one licensed march of a few hundred in Quebec City proceeded with heavy cordons, ending peacefully with only three arrests. Critics noted that such overwhelming force served mainly to chill dissent. The Council of Canadians and Montreal protest organizers decried the de facto “trap” of La Malbaie – calling it a setup to keep genuine demonstrators out. Journalists were mostly free to work (unlike Biarritz 2019), but the pre-emptive tone (“we will be ready for the worst-case”) sent a clear message that any unpermitted gathering would be met by force.

Charlevoix produced virtually no legal aftermath. The few trespass arrests (e.g. for blocking a road) were minor and resolved in Québec courts. There were no large lawsuits as in Toronto or Genoa. At most, civil liberty groups issued post-summit critiques of the heavy-handed security, but no formal commission was convened. In short, Charlevoix passed with little incident and little accountability: it demonstrated that merely preparing for violence can stifle protest with minimal legal challenge if none actually occurs.

France’s G7 (Aug 24–26, 2019) at Biarritz saw an unprecedented security cordon. The government deployed 13,000 police and gendarmes, imposing a wide “neutral zone” around the luxury resort. All public demonstrations were banned in Biarritz and nearby towns. Surfers were barred from the main beach, the airport and train station were closed, and roadblocks at the Spanish border were set up. On the eve of the summit (Aug 23), riot police clashed with hundreds of activists camping near Urrugne (Basque Country). Officers fired tear gas and flash-balls (LBD-40 rubber bullets) into the crowd. By summit’s end, about 100 people had been arrested during protests and police operations. Many arrests were scripted: for example, on Aug 25 police cleared a spontaneous march in Bayonne, detaining dozens and burning nearby barricades.

French authorities openly invoked the specter of “anarchist” and “violent” protesters (often Gilets Jaunes affiliates) to justify the clampdown. President Macron warned of “groups of violent protesters” seen at every G7/G20. Interior Ministry directives emphasized zero tolerance. In the days before Aug 24, police arrested five activists for social-media posts allegedly inciting attacks on a police hotel. Intelligence services used aerial surveillance and pre-emptive authorizations to rapidly identify any gathering. Amnesty International noted that the construction of a special 300-person holding cell and 17-prosecutor court in Bayonne signaled a plan for mass arrests. In sum, France treated the summit as a high-risk security operation, with planners assuming violent conspiracy as a baseline.

The Biarritz summit effectively nullified the right to protest in the region. Hundreds of kilometers of southern France were declared sensitive areas. All traditional protest tactics (marches, sit-ins, village camps) were banned; activists faced hefty fines if they approached the resort. Journalists and observers reported arbitrary abuses: Amnesty staff were blocked from entering the zone, and human-rights monitors from LDH were detained (fingerprinted, strip-searched) on vague charges of “criminal association” before being released. Over 70 of the roughly 100 detained were held in pre-charge detention (comparative custody – a sharp departure from ordinary protest policing. Police repeatedly used tear gas and water cannons against small groups (in Bayonne and Hendaye). Meanwhile, authorities set up a special “super-jury” court on site, enabling swift preliminary hearings. This orchestration drew heavy criticism. Amnesty France warned that treating protesters with “contempt” – jailing them en masse without individualized evidence – violated basic assembly rights.

Domestically, the French government declared the protests quelled and defended its actions as necessary. A few legal challenges later contested the sweeping bans, but French courts generally upheld police prerogatives during the summit (notably, the Conseil d’État allowed broad decrees forbidding protest gear like masks and gaz masks). In practice, none of the mass arrestees were charged with serious crimes; most were released without trial or given minor fines for violating demonstration bans. Internationally, human-rights NGOs decried Biarritz as a sign of France’s “climate of fear” around summits. No officers have been prosecuted for brutality. The episode exposed the gulf between France’s climate rhetoric and its domestic repression; as one group put it, Macron’s “climate superhero” image rang hollow when activists were clubbed and gassed.

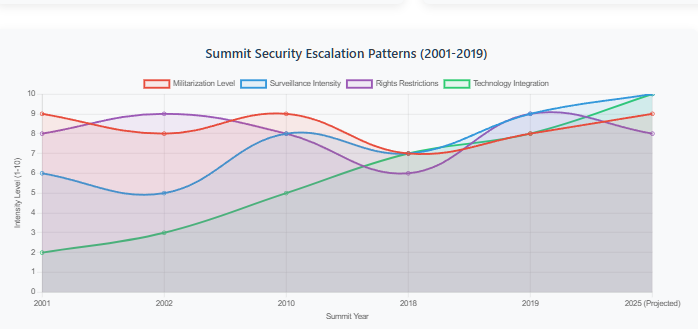

Across these cases, common themes emerge. Summits are consistently treated as security sieges rather than public events:

As Canada prepares to host (or support) the next G7, the above patterns warn of intensifying conflict at the next summit. New technologies and protest tactics will shape this contest:

Our analysis suggests Kananaskis 2025 is likely to see a continuation of previous failures, but on a higher technological pitch. Authorities will probably plan for mass non-violent marches (even if unlikely), over-deploy AI surveillance to ID “unrest leaders,” and prep militarized responses (armoured vehicles, heavy baricades). Protesters, learning from history, will try to exploit freer environments (e.g. cities or online) to avoid isolation. Without meaningful transparency (e.g. advance publication of police plans) and legal clarity (rules of engagement, limits on data use), a new escalation of rights infringements is probable. Civil rights observers should monitor AI and drone usage, demand clear rules on digital surveillance, and insist on judicial oversight of any new powers. Diplomatic or public pressure after Kananaskis could push for accountability – but that will only come if watchdogs document the unfolding security operations now.

The 2025 G7 in Kananaskis will not be policed in a vacuum—it will be shaped by the legacy of Genoa’s torture, Toronto’s mass arrests, and Biarritz’s protest bans. What’s new is the scale of the surveillance infrastructure: biometric databases, drone fleets, predictive policing algorithms, and real-time social-media monitoring now constitute the security backbone of global summits. These tools give police the ability to preemptively neutralize dissent, often without oversight or recourse. As the summit unfolds behind fences, firewalls, and flight restrictions, the real contest is for civil society’s right to exist in that space. Without judicial constraints, transparency mandates, and watchdog reporting, Canada risks reproducing the same pattern of overreach, impunity, and erasure that has marred summits for two decades. The world is watching—not only the leaders, but how those who question them are treated.