Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

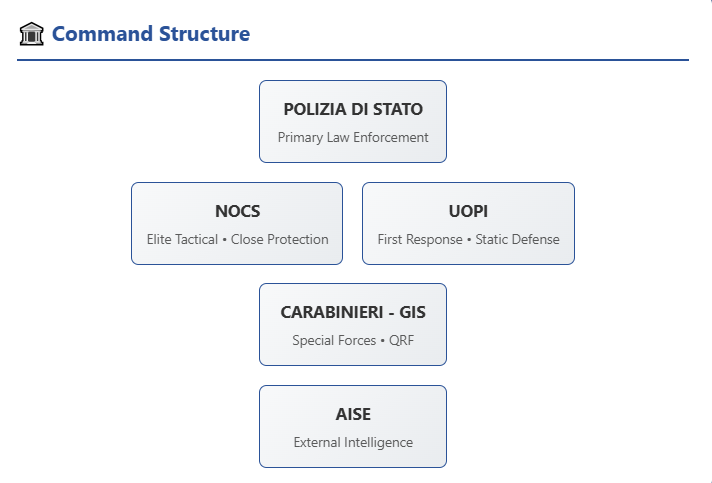

As the G7 Summit in Kananaskis approaches, Italy dispatches a security architecture shaped by both domestic threat experience and multilateral interoperability. Operating under the banner of the Polizia di Stato, the Carabinieri, and Italy’s foreign intelligence apparatus, Italian security personnel bring an agile, tri-service structure: NOCS for elite counterterror protection, UOPI for first-response and static defense roles, and GIS as a potential military quick-reaction force. Supporting them is AISE, Italy’s external intelligence agency, embedded alongside Canadian partners in the summit’s classified fusion node. From armored Alfa Romeos to VIP airlift patterns, this profile maps how Italy projects national protection capability abroad—operating within Canada’s legal framework while retaining a sovereign edge.

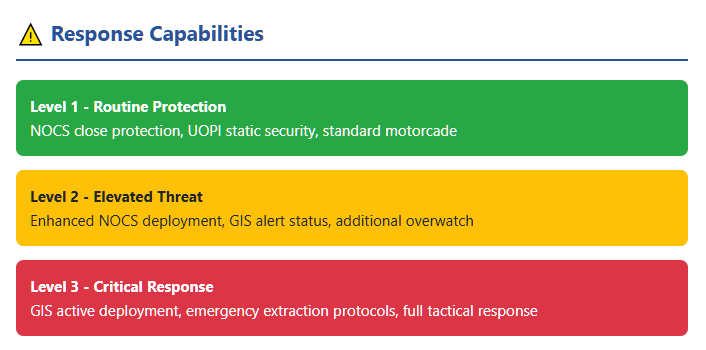

These are specialized first-response units of the Polizia di Stato designed to react to terror attacks or high-risk incidents domestically. UOPI teams are stationed in Crime Prevention departments and major airports (e.g. Malpensa, Fiumicino) and are equipped for quick intervention with rifles, body armor, and ballistic shields. While primarily a domestic asset to contain threats until NOCS arrives, UOPI operators may augment overseas security details in a support role. For foreign deployments (like G7 summits), Italy might dispatch a small UOPI element to reinforce perimeter security or protect key locations (e.g. the Italian delegation’s hotel or aircraft) under the coordination of NOCS and host nation police. Their formation is typically in 4-5 person teams with robust firepower (Beretta ARX-160 rifles, MP5 SMGs, etc.) and high visibility gear to deter attacks. The RCMP – as Canada’s lead agency for VIP protection and summit security – liaises directly with foreign security details. Italy’s team will work under the umbrella of the RCMP-led Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG).

NOCS is the elite tactical unit of the Polizia di Stato, analogous to a SWAT/Counter-terrorism team, and does deploy with Italian officials abroad. NOCS has a broad mandate including hostage rescue, high-risk arrests, and protection of high-profile Italian dignitaries in danger, as well as foreign VIPs in Italy. Within NOCS, there is a dedicated VIP protection division, although VIP protection is not their daily mission except for high-threat scenarios. For overseas summits, NOCS operators are embedded in the Prime Minister’s close protection detail, especially if credible threats exist. They typically handle close protection and tactical overwatch: for example, NOCS may position sniper/observer teams on rooftops, provide a counter-assault capability near the PM, and secure immediate surroundings of Italian VIPs. Their equipment is military-grade (compact SMGs, assault rifles, sniper rifles, breaching gear), enabling them to respond to complex attacks. At Kananaskis 2025, it is expected that a small NOCS contingent will accompany the Italian delegation, working in plainclothes within the motorcade and at venues.

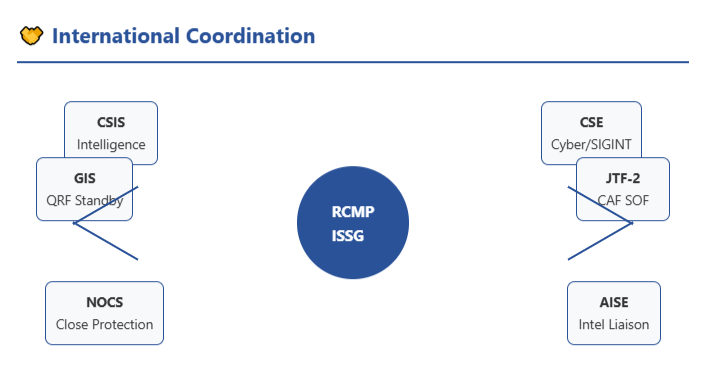

Italian security teams will closely coordinate with the RCMP and the Integrated Security Unit in Canada. The RCMP is the lead agency for all VIP protection on Canadian soil, so Italian officers function in a support capacity under RCMP’s security umbrella. In practice, Italy’s security detail attends joint planning meetings and daily security briefings led by the RCMP’s Integrated Safety and Security Group (ISSG). They establish liaison channels — for example, an Italian security liaison officer will be embedded at the RCMP command center to share information. Rules of engagement and emergency protocols are pre-arranged: Italian NOCS operators would act only in last-resort defense of their PM, and even then likely side-by-side with RCMP close protection. Italian and Canadian teams are known to practice interoperability, such as radio communication checks and emergency extraction drills, to avoid confusion during an incident. Collaboration extends to allied special teams as well: other G7 nations (US Secret Service CAT, UK SCO19 or SAS attachment, etc.) similarly bring close protection or counter-assault units. Informally, these teams exchange information on protective plans and may establish an ad-hoc network during the summit (for instance, nightly meetings of all countries’ security leads). This ensures that if a multi-pronged threat emerged, the various national teams and host forces can de-conflict their responses. Bottom line: UOPI and NOCS form Italy’s forward security echelon – NOCS providing elite counter-terror protection, and UOPI (if deployed) offering reinforced coverage – all operating in lockstep with Canadian security authorities.

GIS is the Carabinieri’s renowned special forces unit, and it does have precedent for overseas security operations. By charter, GIS can operate internationally for counter-terrorism and to protect Italian interests (they have guarded Italian embassies and officials in high-risk zones abroad). While routine PM protection is handled by dedicated police/bodyguards, in high-threat environments or major events the Italian government can deploy GIS as an added protective resource. This was seen in May 2017 when GIS operators were actively involved in securing the G7 summit in Taormina, Italy, protecting world leaders on site. For foreign summits like Kananaskis 2025, it is plausible that a small GIS detachment will be pre-positioned in Canada to bolster Italy’s security contingent. Officially, these Carabinieri would be part of the delegation’s military staff or listed as diplomatic security officers, giving them legal cover to operate.

As a unit of the Carabinieri (which is both a military force and a police agency), GIS deployments abroad usually occur under a clear mandate. They may be authorized by the Italian Ministry of Defense or Interior as a protective mission. The scope of their mission at a foreign G7 would center on counter-terrorism quick reaction and hostage rescue capabilities in defense of Italian VIPs:

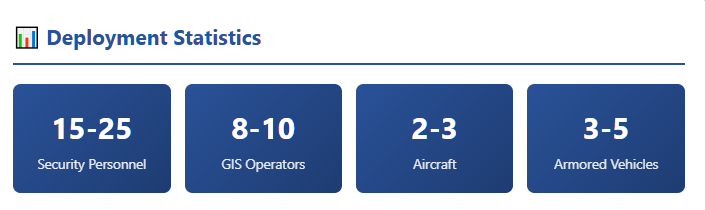

The threat level and political decision will determine if GIS deploys to Kananaskis. Given current global concerns and significant threat matrix facing the 2025 G7 in Kananaskis (the GIS commander noted an unprecedented turbulent context of jihadist and Russian threats in 2024-2025) and the remote location of the summit, Italy may err on the side of caution. A small team (perhaps 8–10 GIS members) could be sent. They might travel on the same aircraft as the delegation or via a military transport, arriving discreetly. These operators would likely remain low-profile – not overtly visible to the public – and integrate with the Italian Embassy’s staff or military attaché office during their stay. Italy’s legal framework allows such deployments under the umbrella of protecting national interests abroad, and Canada’s summit security framework can accommodate allied special teams as long as they coordinate with the RCMP. In summary, GIS’s presence would provide Italy with a highly-trained counter-terror unit on standby, acting as a national insurance policy should a crisis (hostage-taking, severe attack) threaten their leaders or citizens at the G7.

The Agenzia Informazioni e Sicurezza Esterna (AISE), Italy’s external intelligence service, plays a pivotal behind-the-scenes role during summits. In preparation for 2025, AISE has been actively liaising with Canadian intelligence agencies, chiefly CSIS (Canadian Security Intelligence Service) for human intelligence and threat assessments, and CSE (Communications Security Establishment) for signals and cyber intelligence. This liaison ensures Italy is plugged into the host nation’s threat picture – for example, any local extremist activity, plots, or cyber threats in Canada that could affect the G7 will be shared through intelligence channels. Canada and Italy, both NATO allies, already cooperate on intelligence via NATO structures and bilateral agreements. For the G7, this cooperation intensifies through classified exchanges and joint analytical efforts (often facilitated by NATO and EU intelligence-sharing frameworks). Protective intelligence is a priority: AISE analysts work with CSIS to identify any plots specifically targeting the Italian delegation or venue. They also coordinate on monitoring of protest groups, extremist travelers, or communications that indicate hostile intent.

Italy typically assigns security or intelligence attachés to its embassies abroad who serve as the point persons for liaison. In Ottawa, the Italian Embassy has officials (from AISE and the security services of the Polizia di Stato or Carabinieri) whose mandate is to coordinate security cooperation. In the G7 context, these attachés are reinforced. Well before the summit, AISE ldispatched additional officers to Canada under diplomatic cover, both to the Embassy in Ottawa or temporarily to the Consulate in Calgary, to assist with summit prep. These officers engage in the host country’s intelligence fusion center for the event. (Canada will run an integrated intelligence center for the G7, combining inputs from CSIS, RCMP, military intelligence, etc., and liaising with G7 partner agencies.) Italian attachés ensure AISE’s intelligence feeds into this center and that Italy receives all pertinent threat updates in real time. They also facilitate any special requests – for instance, if Italy has specific intel about an individual of concern possibly traveling to Canada, AISE attachés relay that to Canadian authorities for action (and vice versa).

Through partnerships like NATO and the EU, Italy can leverage broader SIGINT (signals intelligence) support. AISE works with partner agencies in Europe and the Five Eyes network (Canada is a Five Eyes member) to cast a wide net for communications suggesting threats to the summit. While Italy is not a Five Eyes member, it does have collaboration agreements and often receives intel through NATO channels. In practice, CSE and AISE might coordinate monitoring of extremist communications on the deep web or known channels; any Italian-language threat chatter (e.g. anarchist or anti-globalist groups with Italian links) would be flagged to AISE and shared onwards. Similarly, Italy’s cyber defense units under AISE keep an eye on potential cyber-attacks (e.g. against summit infrastructure or the Italian delegation’s communications) and share findings with Canada. EU intelligence bodies (such as INTCEN) also serve as a conduit for threat information among European G7 members, complementing bilateral efforts.

The end result of these efforts is a protective intelligence fusion cell that includes Italian input. AISE officers will sit side-by-side with Canadian analysts during the event, examining any incoming reports (from informants, intercepts, open sources) for relevance to VIP protection. Information is rapidly disseminated to the Italian security detail if needed. For example, if CSIS learns of a potential lone actor targeting the summit, AISE will ensure the Italian PM’s guards are alerted with descriptive details. This tight loop between intelligence and physical protection is crucial. Additionally, AISE’s presence means Italy can independently assess threat data – providing their own perspective and ensuring nothing is missed that might specifically impact Italian interests. All these measures take place under the legal/diplomatic framework of the summit: foreign intelligence personnel are given privileges and immunities as part of the official delegation, allowing them to operate on Canadian soil in an official capacity. In essence, AISE works hand-in-glove with Canadian intelligence to pre-empt threats, enabling Italian decision-makers and security chiefs to act with timely, shared information.

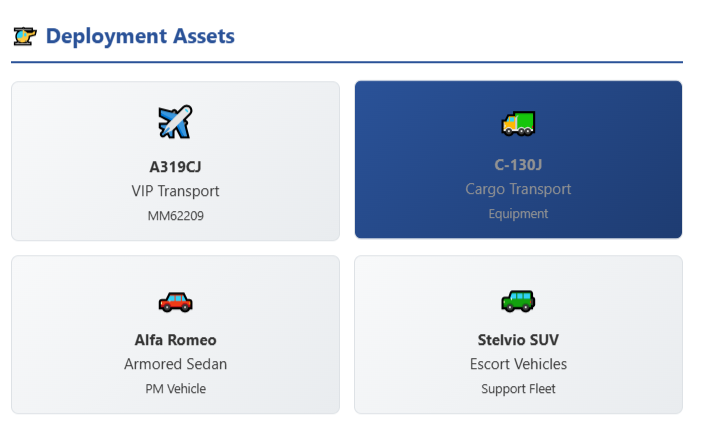

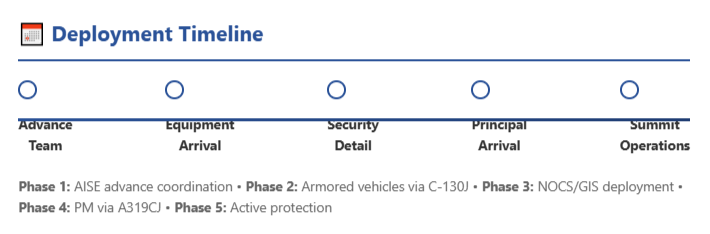

Italy’s government typically utilizes aircraft from the 31º Stormo (31st Wing) of the Italian Air Force for VIP transport. For an overseas summit like G7 in Alberta, the primary aircraft will likely be an Airbus A319CJ in Italian Air Force livery. The 31st Wing operates three Airbus A319 Corporate Jets (tail numbers MM62174, MM62209, MM62243) configured for VIPs. Notably, MM62209 has been used frequently for prime ministerial travel. These aircraft have extended range for transatlantic flights; a non-stop Rome-Calgary flight is near the limit, so a tech stop (e.g. in Iceland or Goose Bay) might be scheduled if necessary. The “Italian Air Force One” A319CJ includes secure communications and a conference area, supporting the PM’s needs en route. In addition to the A319CJ for personnel, Italy could dispatch a support aircraft. This may be a KC-767A tanker/transport or C-130J Hercules to carry heavy equipment and additional staff. The 46ª Brigata Aerea (46th Air Brigade) operates C-130J cargo planes that can be tasked for such missions. If Italy chooses to bring armored vehicles or other bulky gear, a C-130J flight from Pisa or Pratica di Mare air base carrying those items would be coordinated to arrive ahead of the summit. (The Italian Air Force keeps a C-130 on standby for urgent deployments of GIS or other forces, which could be repurposed for summit logistics if needed.)

Italy must decide whether to ship its own armored vehicles or rely on host-nation vehicles. Many countries prefer to use their official state cars for their leaders for reasons of security and familiarity. The Italian Prime Minister’s official car is currently an armored Alfa Romeo sedan (Giulia), adopted under PM Giorgia Meloni’s tenure in a push to use Italian-made vehicles. This car, equipped with bullet-resistant glass and armor, could be flown to Canada (for example, in the hold of a C-130 or a chartered cargo jet). Italy also has armored SUVs (Alfa Romeo Stelvio models) for escort and support vehicles in the motorcade. Shipping a small fleet of say 2–3 vehicles by air is a complex but routine undertaking for high-security visits – they would be loaded days in advance and flown to Canada, then driven to the summit area under guard. However, if logistical hurdles or cost outweigh the benefits, Italy might opt to use vehicles provided by Canada. The Canadian G7 organizers typically arrange armored limousines and SUVs for delegations (except for the U.S. who always brings their own). Canada in 2018 had a fleet of vehicles for the Charlevoix G7, and likely will for 2025. These would be high-end SUVs (e.g. Chevrolet Suburban, Cadillac or similar) and sedans from government fleets or rentals, all vetted and armored to a standard. It’s possible Italy’s delegation will use a mix – for instance, the PM rides in Italy’s own armored sedan for top security, while the rest of the delegation uses Canadian-provided vehicles.

The Italian PM’s motorcade in Kananaskis will be integrated with the RCMP’s route security plan. A typical formation might be: RCMP lead vehicle (clearing the route), followed by the Italian PM’s armored car, then one or two Italian support/close protection vehicles (carrying NOCS agents, medical staff), and then RCMP or Canadian military police tail vehicles. If Italian drivers are used, they will coordinate closely with RCMP drivers and likely do route reconnaissance drives beforehand. Italian security drivers are highly trained, often Carabinieri or police who specialize in protective driving, and they may insist on driving the PM’s car even in Canada. The vehicles will carry Italian and Canadian diplomatic license plates as needed, and the PM’s car typically displays a small Italian flag and possibly the Canadian flag to signify the protectee’s status. Motorcycle outriders in Canada (from RCMP or local police) will escort the convoy; Italy is unlikely to bring motorcycle police, so they’ll rely on the host for that function.

All G7 leaders’ aircraft will converge at Calgary International Airport (YYC) around the summit start. There will be a tightly choreographed diplomatic arrival sequence. Italy’s Airbus A319CJ will coordinate arrival time with Canadian authorities to receive the appropriate ceremonial welcome and security screening. Upon landing, the Italian delegation likely disembarks on a ramp with minimal fanfare (these are working landings, not state visits). RCMP and Canadian military units secure the tarmac. Italian security officers will have arrived on the same plane and immediately take up positions around their principal. If Italy’s vehicles were airlifted, they would be offloaded either at YYC or at a military field (possibly CFB Cold Lake or Springbank Airport if used for logistics) before the summit and staged for the motorcade. Convoy movements from Calgary to Kananaskis (approximately 1.5 hours drive) will be under heavy escort; Italy’s vehicles (whether their own or provided) will slot into a larger motorcade managed by RCMP for the highway journey. En route, Italian close protection rides with their VIP, while Canadian police lead and trail. The sequencing of aircraft departures at the end of the summit will likewise be coordinated – Italy’s delegation must be ready to move on schedule as airports enforce strict time slots. Italian Air Force pilots work with Canadian air traffic control for any special requirements, and diplomatic clearances are in place so that, for example, if the Italian A319 needs to depart on short notice (contingency evacuation), it can do so with priority.

Within the secured perimeter of the Kananaskis resort, leaders often use multi-lateral transport provided by the host (such as shuttles or golf carts for moving between facilities) under guard. Italian security will vet any such shared transport or might insist on using their own vehicles for even short distances if risk warrants. However, given the secure cordon, it’s common to have a more relaxed inner-zone transport plan. Still, the Italian delegation will maintain readiness to exfiltrate the PM quickly by vehicle or even helicopter if an emergency occurs. Italy has AW139 helicopters in its fleet, but they are unlikely to deploy helicopters to Canada. Instead, they’d rely on Canadian air assets (RCMP or RCAF helicopters stationed for summit medical evacuation or emergency transport). All these logistics are planned jointly in advance – Italian officials participate in host-country planning meetings to ensure their needs (from hangar space at the airport to motorcade parking and refueling) are met smoothly.

The presence of armed foreign security agents in Canada is governed by diplomatic agreements and Canadian law. Under the Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act and specific orders for events (such as Canada’s 2025 G7 Presidency Privileges and Immunities Order), foreign delegation members – including security officers – are granted privileges and immunities necessary to perform their duties. Practically, this means Italian security personnel are part of the official delegation list submitted to Global Affairs Canada, often with diplomatic or official passports, giving them a status that can include immunity from local prosecution for actions in the line of duty. Canada entrusts primary responsibility for VIP protection to the RCMP by law, but it permits foreign protectors to carry firearms and exercise limited protective authority as an extension of their principals. This permission is typically formalized through a combination of diplomatic notes and RCMP accreditation. In some cases, RCMP may designate foreign agents as “special provincial constables” for the duration of the event, which legally empowers them (under RCMP supervision) to bear arms.

Italian protective details will be armed with handguns (e.g. Beretta or Glock pistols) and possibly small submachine guns in vehicles, consistent with their standard equipment. Canadian authorities require that all foreign weapons (type and serial number) be declared in advance. The weapons are typically bonded (registered) for the event and can only be carried by named individuals. The understanding is that foreign agents use their weapons solely to protect their dignitary from an imminent threat – any offensive or law enforcement action is left to Canadian police. Should an Italian security officer need to discharge a weapon in an extreme situation, the legal coverage comes from their status as a person protecting an “Internationally Protected Person” (the PM), which international law and Canadian law recognize as a justified role. The RCMP’s integrated command structure means that an RCMP officer is usually nearby or embedded with each motorcade and can technically authorize or at least acknowledge any use of force by foreign security. All parties train to avoid crossfire and mistaken identity; for example, Italian agents will wear discreet identification (such as lapel pins or colored arm bands) that Canadian officers recognize, especially during an incident.

While there may not be a public, standing bilateral treaty specifically between Italy and Canada on summit security, there is a strong precedent of cooperation. For instance, during the 2010 G8/G20 in Canada and 2018 G7, foreign security teams (including Italy’s) were allowed to operate armed under RCMP coordination. Those arrangements set a template: foreign teams must respect Canadian sovereignty (RCMP is in charge), but Canada acknowledges the reality that each leader’s security will act immediately to protect their own principal. Any incidents of concern (e.g. an armed foreign agent inadvertently violating a law) are handled diplomatically rather than through arrests, thanks to immunity. Additionally, Italy and Canada law enforcement have cooperative MOUs through Interpol and directly, which cover information sharing and could extend to supporting each other during major events. If needed, Italy might request specific legal exemptions (for example, to use electronic jamming gear for convoy protection) and Canada can grant temporary licenses for such equipment.

The legal chain of command is clear: the RCMP ISSG is the unified command for summit security. Italian security team leaders are integrated into that structure. In the event of any use of force, post-incident investigations would be led by Canadian authorities (to satisfy Canadian law and public accountability), but because of diplomatic status, Italian agents would not be subject to local prosecution barring extraordinary circumstances. Instead, any issues could be addressed at the government-to-government level. Both countries strive to prevent such issues by exhaustive pre-planning: Italy’s security personnel have already likely undergone briefings on Canadian law (e.g. rules of engagement, definition of self-defense in Canada, etc.). Summary: Italian protective agents operate in Canada under a veil of diplomatic immunity and with host-country consent. They are armed and empowered to act to save lives, but they coordinate every step with Canadian counterparts to ensure all actions fall within agreed-upon legal parameters and do not conflict with Canadian jurisdiction.

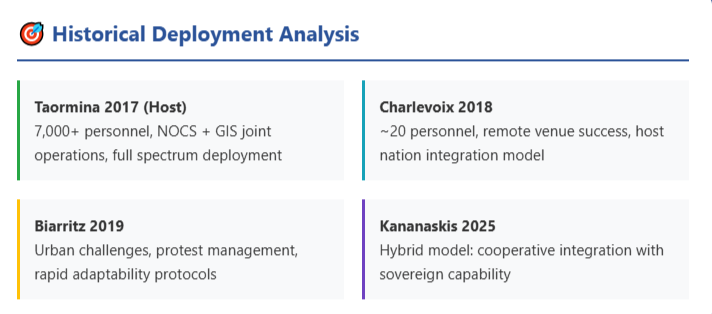

When Italy hosted the G7 in 2017, it fielded a massive security operation on home soil. This included 7,000+ security personnel from police, Carabinieri, and military. Notably, Italy deployed both NOCS and GIS in protective roles, working hand-in-hand to secure the event. NOCS and Carabinieri GIS operators were positioned for overlapping responsibilities – NOCS focusing on immediate VIP close protection and urban counter-terror tactics, and GIS providing special forces support (counter-sniper, hostage rescue capability). Overwatch teams were on every strategic rooftop in Taormina, and Italy even utilized anti-drone systems and naval assets off the Sicilian coast. One lesson from Taormina was the value of multilayered defense: local Carabinieri units secured outer perimeters and conducted crowd control, while elite units (NOCS/GIS) formed a rapid intervention layer close to the principals. The coordination between NOCS and GIS during Taormina set a precedent that these two units can jointly protect high-level events – a practice Italy can replicate abroad by sending elements of both as needed.

In Charlevoix, Quebec, Canada’s remote venue provided a template similar to Kananaskis. Italy, as a visiting delegation, sent its core close protection team. Although details are not public, it’s likely Italy’s delegation included around 15–20 security personnel in 2018, including close protection officers, advance security officers, and a small tactical team (NOCS). These personnel integrated with the RCMP-led Integrated Security Unit. A key point from Charlevoix was the effectiveness of a remote, hardened site: protests were kept far from the leaders, reducing direct confrontations. Italian security worked within a tightly controlled zone, mostly focusing on protecting the Prime Minister’s movements between the airport, hotel, and summit site. With no major security incidents during Charlevoix, the event demonstrated the success of preventive coordination – threat information was shared ahead of time and strong perimeter security prevented disruptions. For Italy, Charlevoix reinforced that trusting the host nation (Canada) for overall security while concentrating on immediate close protection yields a safe outcome.

Biarritz presented a different challenge – an urban coastal city, with significant protests and rioting in nearby areas. Italy’s then-Prime Minister and delegation were protected by a combination of Italian agents and the host nation’s forces (French Gendarmerie and Police). One notable aspect was that the French GIGN and RAID units were on high alert; thus Italy did not bring heavy assets like GIS, relying on France’s renowned counter-terror units if needed. However, Italy’s own Carabinieri Tuscania paratroopers (military police) were reportedly sent to help guard the Italian Consulate in France during that period, illustrating Italy’s habit of securing its facilities even abroad. The turbulence in Biarritz underlined lessons about crowd management and the need for rapid adaptability – something Italy’s team experienced first-hand. They had to navigate road blockades and potential violent protests when moving the delegation. From this, Italy likely took away improved protocols for motorcade rerouting and safe haven locations in case a planned route is compromised by unrest. Biarritz also reinforced close ally cooperation: Italian and French security heads were in constant contact. This kind of cooperation will similarly be critical in Canada, ensuring that if protests or other disruptions occur, Italy’s delegation can be rerouted or extracted swiftly with Canadian help.

NATO summits in Brussels involve many of the same leaders but in a heavily secured international city. Italy’s approach for NATO has been to send a streamlined protective team (close protection officers from Polizia di Stato and a few NOCS for tactical support), given that NATO HQ itself is a secure compound guarded by Belgian and NATO security. In 2018, when a NATO Summit coincided with heightened terrorism concerns in Europe, Italy kept some GIS operators on alert in Italy and possibly at its Embassy in Brussels as a forward deployment. The lessons from NATO summits are about operating in a multi-national security environment: Italian officers had to coordinate not just with the host nation (Belgium) but with NATO’s own security staff and those of other allies. This is analogous to G7 settings where multiple national teams are present. Italy learned the importance of clear communication channels – for example, establishing a dedicated radio channel or WhatsApp group among G7 security liaison officers to share urgent info in real time. Additionally, after observing the 2018 NATO Summit, Italy would appreciate robust counterintelligence measures – Brussels saw intense cyber espionage attempts, so protecting communications (encrypted radios, secure phones) for the Italian delegation became a priority. The experience honed at NATO and other summits (like the G20s or COP conferences) feeds into Italy’s preparation for Kananaskis: they will arrive with a playbook refined by these comparisons, emphasizing advance reconnaissance, contingency planning, and trust-building with host security.

Over recent summits, Italy’s protective posture has evolved to be highly adaptive:

Italy’s security footprint at G7 Kananaskis reflects a doctrine of disciplined modularity: NOCS and UOPI for visible deterrence and kinetic response, GIS in latent readiness for edge-case threats, and AISE embedded in intelligence exchanges that fuse tactical and strategic foresight. Unlike the more expansive American footprint or the minimalist UK model, Italy fields a hybrid model: not overwhelming, but never under-prepared. Whether through encrypted briefings at the RCMP command center or a Beretta holstered under a plainclothes jacket, Italian protective forces maintain a consistent pattern—cooperative, confident, and legally mapped. For observers, the true sign of success will be invisibility: if Italy’s security apparatus fades seamlessly into the summit’s security matrix, it will mean the architecture held.