Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

On June 12, 2025, the Sheldon M. Chumir Health Centre in downtown Calgary felt unusually tense. I arrived with a routine injury, but amid the normal ER bustle were subtle signs of summit fever. A uniformed peace officer at the intake quietly mentioned they were bracing for “protest injuries” in the coming days. Over the course of a seven-hour wait for treating another Achilles tendon issue engendered by my puppy Wilco, at least five different staff members – from nurses to support staff (not the lovely physicians, nurses and allied professionals treating me once admitted) – independently confirmed that a “lockdown” plan was in place for the facility during the G7 Leaders’ Summit. Their tone was calm and matter-of-fact, as if such preparations were standard procedure. “I can’t share much, but let’s just say we’re ready for anything,” one nurse said with a wry smile, implying far more than she explicitly stated. This loose-lipped acknowledgment of protest contingency (arguably poor OPSEC on their part) hinted that Alberta’s health infrastructure was being quietly integrated into the summit’s security and emergency response framework. It raised an unsettling question: Why were hospitals steeling themselves for protest casualties before a single march had even begun?

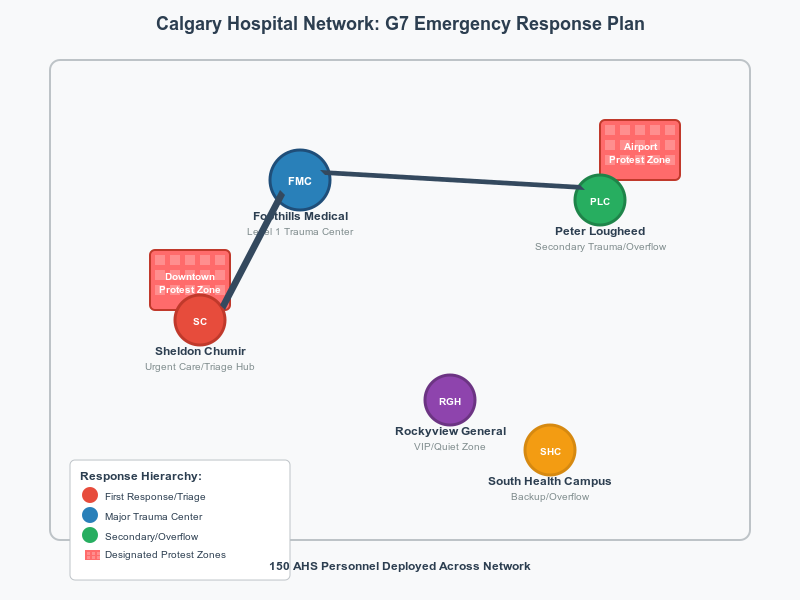

Well before any protesters take to the streets, Alberta Health Services (AHS) has been deeply involved in preparing for the 2025 G7 Summit. In fact, AHS began planning its medical response in 2024, coordinating with the G7 Integrated Security Unit led by the RCMP. An AHS sourced noted, the health system is being readied for “a variety of scenarios, including disease outbreaks and mass casualty incidents,” in anticipation of summit-related events. This planning is comprehensive: 150 health personnel are slated for deployment to key sites in Calgary and along the Bow Valley corridor during the summit period. In practice, this means extra paramedics, nurses, and physicians on standby at hospitals and field clinics to support what authorities call a “whole-of-government” operation.

Behind the scenes, AHS officials have been embedded in the multi-agency Major Events Coordination Centre (MECC) that the RCMP activated for G7 security. It is standard for large-scale events to stand up unified command posts, and health services are a crucial part of these. Emergency planners from AHS have coordinated with police, the RCMP, and municipal officials to run joint exercises simulating worst-case scenarios. This ensures that if protests turn unruly or any disaster strikes, medical responders are already plugged into the communication loop with law enforcement and emergency management. While formal Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) aren’t always public, past summits suggest that protocols exist linking hospitals and EMS with police operations. For example, during the 2010 G20 summit in Toronto, an on-site medical team at the police detention centre significantly reduced the number of injured detainees sent out to hospitals. Only five arrestees in that event had injuries severe enough to require hospital treatment – a statistic achieved in part because police had integrated medical support into their operations. Alberta authorities have taken a similar integrated approach for 2025: AHS’s emergency coordination center will run in parallel with (and connected to) the RCMP’s command centers, prepared to triage anything from a multi-car motorcade crash to a downtown crowd stampede.

Crucially, an AHS source notes that all Calgary hospitals have robust and multi-tiered emergency response and lockdown plans in place for scenarios ranging from mass casualty events to food-borne illness outbreaks all the way to CBRN scenarios. Summit planning simply activates and augments those existing plans. Health leaders emphasize this is not overkill but prudent preparedness. “We plan for the worst and hope for the best,” as the saying goes. By quietly folding hospitals into the summit contingency framework, officials aim to mitigate harm – whether it’s a delegate falling ill or a protester injured in a clash – with swift, coordinated medical care.

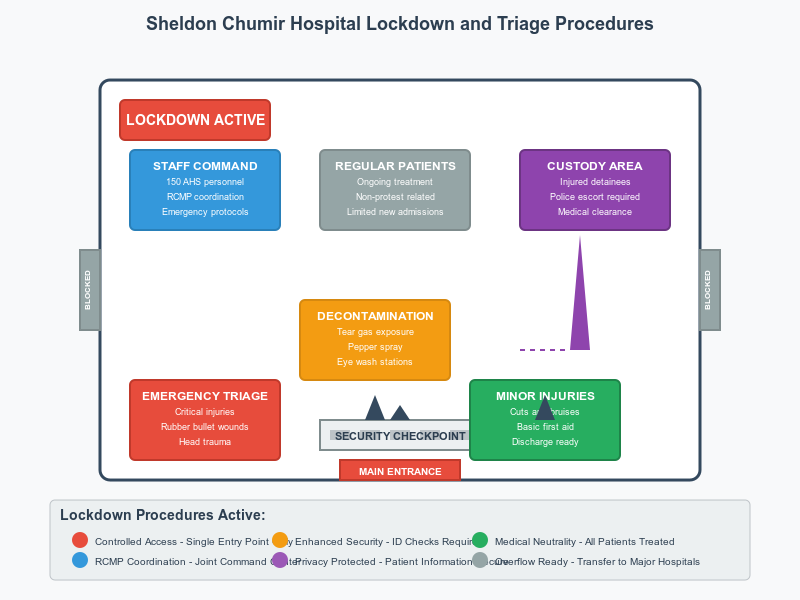

So what does a “lockdown” at an urgent care center like Sheldon Chumir actually entail? Based on staff hints, it doesn’t mean turning the downtown clinic into a fortress so much as controlling access and workflow if protests surge outside. The Sheldon Chumir Health Centre sits in Calgary’s Beltline district – just a few blocks from City Hall, where one of the designated G7 demonstration zones will be. In a scenario where large crowds or a police action erupt nearby, “lockdown” likely means temporarily restricting public entry to ensure the safety of patients and staff. The urgent care would treat existing patients and genuine emergencies, but might defer walk-in cases or redirect ambulances to other hospitals if a security incident is unfolding on its doorstep. Essentially, staff have a plan to secure the facility: doors may be locked or monitored, extra security or peace officers posted at entrances, and non-urgent services scaled back until the situation stabilizes.

This controlled posture also positions Sheldon Chumir to serve as a triage hub for protest-related injuries downtown. If a confrontation were to occur in the core, police or paramedics could ferry the injured – whether demonstrators, bystanders, or officers – to the Chumir’s urgent care for initial evaluation. Those with minor injuries (pepper spray exposure, cuts, bruises) could be treated and released on-site, while more serious trauma (deep lacerations, broken bones, head injuries) would be stabilized there before transfer to a full hospital. In essence, the centre could act as a forward medical post for the civil unrest. One scenario quietly acknowledged by staff is the possibility of detainees being brought in under police escort – already a common site as Chumir because of the fact that it serves a large downtown transient population and contains a “safe injection site.” During mass arrests, it’s standard procedure that anyone hurt or ill must be cleared by a doctor before being lodged in jail – urgent care centers can fulfill this role. Sheldon Chumir’s team, then, might find themselves treating injured protesters in handcuffs, alongside ordinary Calgarians, all under the watchful eye of police guards. It’s a delicate balance: providing care to patients who might also be in custody, all while maintaining a neutral, healing environment. Little wonder the staff speak in hushed, cautious tones about the lockdown; they know their clinic could become an island of triage in a sea of unrest.

For crowd control purposes, AHS has protocols to prevent the health centre itself from becoming overwhelmed. If dozens of tear-gassed demonstrators show up at once, nurses would establish a triage zone – perhaps at the entrance or even outdoors – to sort patients by severity. Those merely suffering from OC spray (pepper spray) exposure could be handed bottles of water or eyewash to decontaminate themselves, whereas people with blunt trauma from rubber bullets or batons would be prioritized for physician care. Restricted access might also mean only one entrance remains open (already generally the case), with ID checks or escorts for anyone coming in, to keep out agitators or to protect staff from any spill-over conflict. These measures sound extreme, but they align with quiet steps Canadian hospitals have taken during past protest events. (In Toronto’s G20, for example, some downtown hospitals increased security at their doors when riots broke out, and one even locked its entrances briefly as a mob moved through the area.) Sheldon Chumir’s preparations reflect lessons learned: in times of civil disorder, the ER must become a controlled sanctuary – open enough to treat the wounded, but shielded enough to remain functional.

Beyond the downtown urgent care, all major Calgary hospitals are on alert as G7 week unfolds. Each facility in the city’s health network has a designated role in a mass casualty or protest-related scenario:

Across all these facilities, there’s specific attention to the types of injuries anticipated. Chemical crowd-control agents like tear gas or pepper spray are a known risk during protests – Calgary’s hospitals are prepared with decontamination protocols (e.g. outdoor rinse stations, supply of saline eye washes and inhalers for those with respiratory distress). Blunt trauma injuries from police batons, shields, or physical scuffles are another category – the ERs will be ready to X-ray for fractures, suture up lacerations, and treat concussions. Perhaps most concerning, projectiles like rubber bullets or “less-lethal” sponge rounds can cause serious wounds. Emergency physicians are well aware that, despite the name, these can penetrate flesh or eyes at close range and break bones at a distance. In Seattle’s WTO protests in 1999, more than two dozen protesters (as well as a few police and delegates) ended up in hospitals mostly for “minor injuries” – but some had been hit with rubber rounds. Calgary’s trauma teams have reviewed such cases from past events in case they see similar wounds. “Any projectile to the head or neck, even if ‘non-lethal,’ we treat as life-threatening until proven otherwise,” one trauma doctor noted in an earlier informal conversation about such munitions. In short, Calgary’s hospitals have drilled on the kinds of injuries summit protesters have suffered elsewhere, hoping they won’t be needed but standing by if they are.

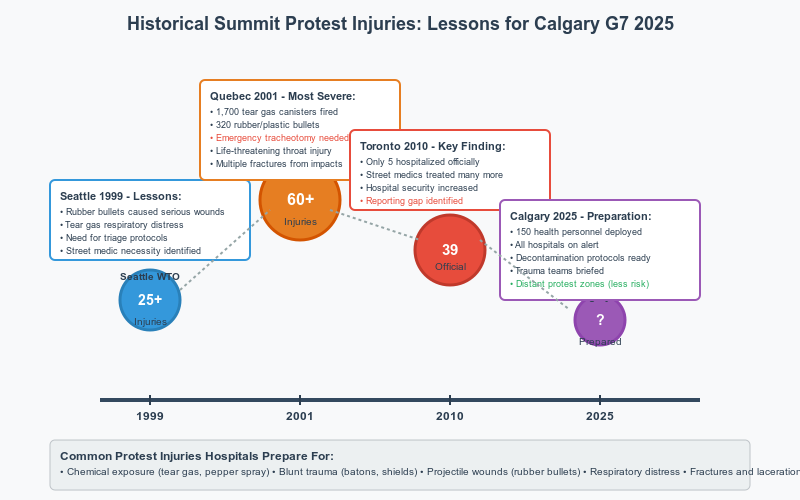

The idea of quietly integrating medical services into protest security planning is not without precedent. Major international summits and events in Canada have long involved coordination between health and security agencies – albeit usually behind the scenes. Toronto’s G20 summit in 2010 is a stark example: over that weekend, police clashes with protesters led to at least 39 civilians injured (and 97 officers injured). Officially, very few of those injured protesters were hospitalized – the Toronto Police Service later reported that “of all those arrested… only five suffered injuries that required they go to hospital.” Unofficially, however, volunteer street medics in Toronto treated many more victims of police batons and rubber bullets on the streets. Teams of medics at the G20 described treating “broken bones, cracked heads and eyes filled with pepper spray” – all injuries “inflicted by the police,” according to a collective of MDs who volunteered as first-aiders. They even escorted several concussion and fracture victims to nearby hospitals for further care. This gap between official injury stats and medic reports suggests many protesters avoided or delayed hospital visits, likely out of fear of arrest or identification. Toronto’s hospitals, for their part, had been on alert that weekend with enhanced security; some downtown ERs saw a trickle of protesters seeking care for bruises, pepper spray exposure, and hypothermia after the torrential rain that accompanied the police crackdown. The G20 taught Calgary a few things: keep minor treatment on-site (to avoid flooding ERs), but also prepare for a surge of walk-ins if something goes very wrong.

Go back further to Quebec City in 2001, during the Summit of the Americas protests, and one finds even more dramatic medical tales. That summit saw police fire 1,700 tear gas canisters and 320 rubber/plastic bullets over a few days. Local clinics and hospitals ended up treating scores of people for chemical exposure and impact injuries. In one widely reported case, a young protester was hit in the throat by a police-fired plastic bullet; she was rushed to hospital and underwent an emergency tracheotomy to save her life. The Red Cross, which had first-aid stations in the protest zone, later confirmed her life-threatening injury and treatment. Many others in Quebec suffered rubber bullet wounds to limbs and torsos, deep bruises, and respiratory problems from tear gas. The lesson taken by health planners: even if protests are planned to be peaceful, one volatile confrontation can yield dozens of patients. Accordingly, for the G7 in Alberta, not only are Calgary’s hospitals preparing, but smaller centers in the Bow Valley (like the Canmore General Hospital and Banff’s Mineral Springs Hospital) have been briefed on mass-casualty procedures. Kananaskis in 2002 (when it hosted the G8) fortunately had minimal violence – by some accounts “so few [protesters] and it was so peaceful that we didn’t even bother to estimate a number,” as a G7 research expert recalled. But authorities aren’t simply banking on a repeat of 2002’s calm. They have studied what if scenarios from other events: the Vancouver 2010 Olympics, for instance, where integrated command centers included health authorities to plan for everything from a terrorism incident to a flu outbreak among athletes. And in the United States, events like the 2017/2025 Trump inauguration protests and various G7/G20 meetings have seen hospitals quietly work with police to be ready, even as public messaging emphasized hopes for non-violence.

A striking feature of Calgary’s 2025 summit security plan is the creation of designated protest zones far from the leaders – two in downtown Calgary and one in Banff – with live video feeds broadcasting the demonstrations to the summit site. This farcical approach, used in 2002 as well, keeps most protesters at a distance and is intended to prevent the kind of direct clashes seen in Toronto or Quebec City. From a medical perspective, this could significantly limit the scale of injuries: contained, policed zones are less likely to devolve into chaos than unplanned marches through city streets. Indeed, experts predict the Alberta G7 protests will be comparatively small and peaceful. However, health planners must be ready for surprises. Even a small peaceful rally can turn hazardous if, say, a few agitators incite police response or if extreme heat/exhaustion hits the crowd. By studying past summits, AHS has tried to anticipate the unexpected – ensuring, for example, extra water and cooling stations if there’s a heat wave (a lesson from a sweltering 2002), or rapid deployment of naloxone kits and medics if an unrelated opioid overdose occurs in a protest gathering (not unheard of in urban rallies – especially in the vicinity of Chumir where overdoses are ubiquitous).

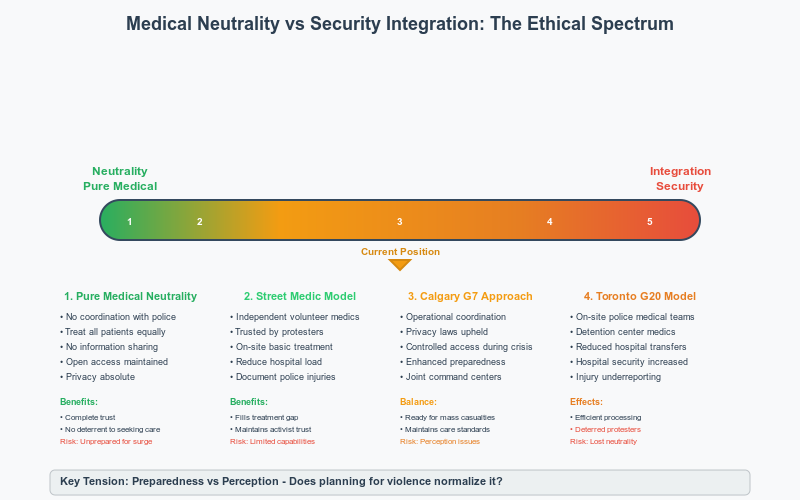

This integration of hospitals into summit security raises deeper ethical questions. In principle, medicine is meant to be neutral – caregivers treat the injured without prejudice, and hospitals are supposed to be sanctuaries from the conflicts outside their doors. In practice, when a major state security operation is underway, can medical institutions truly remain neutral? Critics worry that by participating in security planning, health services edge toward operational complicity. If nurses and doctors are briefed by police about “expected protester tactics” or if hospitals quietly agree to alert police when an injured protester seeks care, the traditional trust between patients and caregivers could erode. Protest movements often have “street medics” precisely because of this concern: activists trust independent volunteer medics to care for them and not share information, whereas they might fear that going to an official hospital could lead to being identified or even arrested once treated. During the Toronto G20, for instance, some street medics reported being harassed and detained by police for simply doing their job – having their bandages and gloves confiscated and being made to feel like criminals. Such incidents underline how easily the line blurs between health aid and policing in a high-security event. Hospitals walk a fine line: they must cooperate with law enforcement on safety (for example, if an armed aggressor followed an injured person into the ER, obviously security is needed), yet they have to uphold patient confidentiality and impartial care. Under Alberta’s privacy laws (FOIP and the Health Information Act), hospitals cannot freely share personal patient information with police unless the patient consents or law enforcement presents a valid legal order. There are narrow exceptions – for example, gunshot wounds must be reported to police by law. It’s conceivable that a rubber bullet injury could trigger that reporting requirement, inadvertently tagging a protester to the police. Apart from such cases, AHS has a duty to protect patient privacy, even if the patient is a protester with controversial motives.

Medical neutrality is also about perception. If would-be protesters believe the emergency rooms are effectively extensions of the security apparatus, they may avoid seeking treatment at risk to their health. This is a serious public health concern: unchecked injuries or medical complications can turn fatal without timely care. AHS officials are likely mindful of this and thus avoid overt actions that would make hospitals seem “in league” with the cops. You won’t see AHS publicly announcing any coordination with police; the integration is deliberately quiet and operational. Ethically, the hope is that by planning ahead, actual harm can be reduced. For example, if police know EMTs are standing by, they might be marginally less hesitant to call in medics immediately when someone is hurt. And if hospitals have a plan to handle mass casualties, that could save lives should violence erupt, without regard to who the patient is. The flipside is that such planning might also signal a form of fatalism – an expectation that protest-related violence will occur, effectively normalizing it. Civil liberties advocates ask: if the state invests heavily in preparing for protest casualties, does that reflect an implicit willingness to use force that causes those casualties? Shouldn’t equal effort go into preventing injuries – for instance, training police to use minimal force – as goes into preparing to treat injuries? These are uncomfortable questions. From the perspective of a hospital administrator, however, neutrality means being ready to treat anyone who comes through the door, whether a demonstrator clubbed by an officer or an officer hit by a projectile. The planning for G7 is intended to ensure exactly that: that whoever gets hurt, and for whatever reason, will get help.

Legal frameworks like the federal Privacy Act and Alberta’s FOIP Act provide some guardrails. They mean hospitals cannot become intelligence-gathering nodes. There will theoretically be no AHS handover of patient lists to the Integrated Security Unit – that would be illegal. If police want information on a patient who isn’t under arrest, they’ll need a warrant. And if a patient is brought under arrest (say a rioter with a broken leg), their health information is still protected – only the necessary details for care are shared with their custodians. These laws strive to keep a wall between caregiving and policing, even as the two systems intersect during events like these. Still, the optics matter: a hospital on “lockdown” with officers at the door sends a message, intentional or not, that the state’s security needs have, for the moment, trumped the free public access to medical care.

As the 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis commences, Calgary’s emergency rooms will be quietly standing by – triage before tear gas, as one might grimly dub it. The fact that hospitals are bracing for protest casualties before a single march occurs is a sobering commentary on the state’s expectations. On one hand, this preparedness is a prudent, responsible measure to mitigate harm. If violence breaks out, fewer people will suffer lasting injury or death because the health system was ready to respond in seconds. In that sense, the proactive stance could be seen as an extension of humanitarian duty: anticipating needs in order to save lives. On the other hand, it also implies an official acceptance that force and injury are essentially baked into the plan. The state is essentially saying: “We know there’s a good chance people will get hurt – and we are gearing up for it.” For critics of heavy-handed summit security, this borders on a self-fulfilling prophecy. Does expecting violence make it more inevitable? If you allocate riot squads, rubber bullets, and yes, hospital lockdowns and surge clinics, are you treating civil dissent as a de facto health hazard to be managed rather than a democratic expression to be facilitated?

In the end, who gets harmed and who gets helped in this arrangement? The calculus of summit security tends to accept that a certain number of protesters may be injured in the name of protecting VIPs and public order. Those individuals – likely young, passionate, and exercising their rights – are the ones who will fill the triage tents and urgent care beds if things go wrong. They will be helped, professionally and compassionately, by the same system that in another capacity may have contributed to their injuries (through sanctioned police action). It’s a paradox that is not lost on the medical staff I spoke with. Their voices carried a tone of resigned duty: we will do our job – patch up the wounds, ease the suffering – even if it shouldn’t be happening in the first place. As for the police and summit delegates, they benefit from the knowledge that any fallout from enforcement will be efficiently handled and unlikely to spiral into a larger crisis. The hospitals’ integration into the contingency plan provides a safety net under the tightrope of summit security.

When hospitals prepare for protest casualties in advance, it suggests a society coming to terms with a distressing truth: that even in peacetime, political conflict can produce battlefield-like injuries. It forces the question of whether this is a healthy expectation in a democracy. Should we applaud the readiness to treat the injured, or lament the apparent inevitability of violence that makes such readiness necessary? Perhaps the answer is both. The doctors and nurses at Sheldon Chumir and across Calgary will stand ready in the coming days with a stoic sort of hope – hoping not to see patients who have been tear-gassed or beaten, but ready to heal them if they do. It is a quiet form of heroism in an uneasy time: the ER as an unwitting participant in the theatre of protest, doing its best to remain a place of sanctuary and care when the streets turn hostile. In that sense, Calgary’s hospitals will fulfill their fundamental mission during the G7 Summit – not taking sides, only saving lives – even as they are subtly co-opted into the machinery that expects those lives to be put at risk in the first place.

Editor’s Note: All of this information is sourced from the public domain and logical inference or from interviews conducted on deep background.