Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

When Washington’s most powerful pull an all-nighter, the food delivery scene in D.C. starts buzzing. Observant sleuths have noticed an uncanny pattern: late-night pizza orders spiking around the White House and Pentagon often foreshadow major events. Dubbed the “Pentagon and White House Pizza Index,” this phenomenon suggests that behavioral OSINT (open-source intelligence drawn from human behavior and routines) can offer early hints of covert operation indicators. It sounds like an urban legend – or a cheesy spy movie trope – but over decades, abnormal DC late-night food deliveries have coincided with military strikes, covert raids, and crisis escalation.

In this deep dive, we’ll explain what the Pizza Index is and how it works, backed by historical case studies from the Osama bin Laden raid to the Soleimani strike. We’ll map out which pizza joints fuel late-night strategizing in Washington, reveal how analysts might track these OSINT signals of war in real time, and discuss the limitations (and ethical quandaries) of basing intelligence analysis on takeout trends. Grab a slice and settle in – it’s time to explore how extra-large pepperonis became small but telling “national security food patterns.”

Pizza as an intelligence indicator – a quirky form of behavioral OSINT. Observers have noted that when crisis strikes, late-night pizza orders to places like the Pentagon often surge, reflecting staff burning the midnight oil.

In intelligence circles, behavioral OSINT refers to gleaning insights from the unintentional signals in everyday activities. It’s pattern-of-life analysis done through open data: think tracking traffic jams outside military bases, unusual late-night office lights, or – in this case – hefty food orders to government offices. The so-called “Pizza Index” is a classic example: a sudden, trackable increase in takeout orders (often pizza) from key government locations like the Pentagon or White House can indicate officials are hunkering down for something big. The logic is simple: when a crisis brews, staffers get stuck in secure meeting rooms, war rooms, and situation rooms. They can’t leave their desks, so they call in reinforcements in the form of pizza and carry-out.

This idea actually has Cold War roots. Reportedly, Soviet intelligence monitored quirky clues like late-night office lights and full parking lots at U.S. government buildings as early-warning signs of impending action. In fact, KGB officers in the 1980s were even taught to count how many lights were on in the Pentagon or how many cars filled its parking lot after hours – figuring a sudden all-hands-at-work at 2 a.m. might mean war preparations are afoot. They even tracked hamburger supply and blood bank levels as obscure indicators of war readiness. In contrast, the Pizza Index zeroes in on a more appetizing metric: junk food deliveries.

“The news media doesn’t always know when something big is going to happen because they’re in bed, but our deliverers are out there at 2 in the morning.” – Frank Meeks, D.C. Domino’s owner

The term “Pizza Index” (or Pizza Meter) itself has percolated through internet lore, OSINT forums, and even a now-removed Wikipedia entry. It’s part of an internet OSINT culture that blossomed post-9/11, where amateur analysts scour open sources – from flight trackers to restaurant reviews – for hints of government activity. While the concept isn’t formally recognized in spy manuals, it’s popular in citizen intelligence communities and meme circles as a tongue-in-cheek metric for looming geopolitical drama. In early 2024, social media chatter about a “Pentagon Pizza Meter” exploded after users noticed D.C. pizza spots flagged as “busier than usual” on Google Maps during a Middle East flare-up. A dedicated X (Twitter) account @PenPizzaReport even now tracks pizzeria activity around the Pentagon in real-time.

In essence, the Pizza Index posits that “pattern of life” signals from civilian life – like a spike in White House pizza delivery requests at midnight – can serve as OSINT signals of war or crisis. It’s an indirect, behavioral indicator that something heavyweight is happening behind closed doors. Of course, correlation isn’t causation (we’ll stress later why ordering pizza doesn’t guarantee a missile strike is coming). But as a veteran CNN Pentagon correspondent famously quipped: “Bottom line for journalists: Always monitor the pizzas.”

“Always monitor the pizzas.” – Wolf Blitzer, covering the Pentagon in 1990

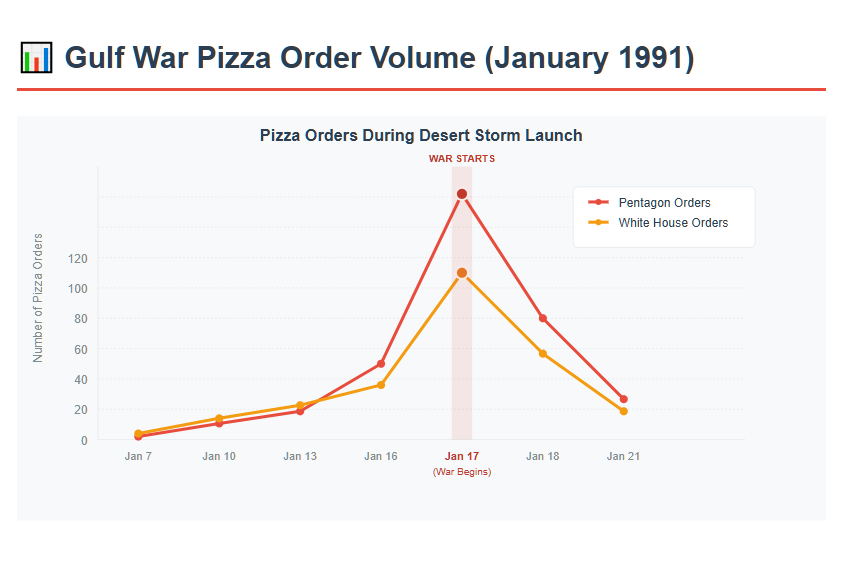

To separate myth from reality, let’s look at known instances where an abnormal flood of pizza (or other takeout) coincided with major U.S. operations or crises. These examples, spanning from the 1980s to the 2020s, show how food delivery became an unlikely barometer of high-level activity:

“That evening, the Situation Room looked like a college fraternity house – so many pizza boxes stacked up.” – George Little, CIA spokesman recalling the bin Laden raid night

In all these cases, the Pizza Index was a behavioral tell – an innocuous commercial signal (pizza sales) reflecting extraordinary government activity. It’s important to note that in each instance the correlation was observed either in hindsight or by insiders; the idea of systematically watching deliveries in real-time is newer. Still, these anecdotes form the lore of pizza delivery intelligence and encourage today’s OSINT analysts to keep one eye on the Domino’s tracker during global crises.

What pizza joints and fast-casual eateries are on speed dial when Washington’s power brokers need a midnight snack? Understanding where the orders come from is key to tracking the Pizza Index. D.C. and Northern Virginia have a network of restaurants that regularly deliver to government offices – some so frequently that their staff know the security guards by name. Let’s map out the key nodes in this “DC pizza delivery intelligence” circuit, including their typical delivery zones and any quirks of dropping food at high-security sites:

Security protocols for delivery: All these deliveries to high-security locations follow strict rules. Generally, drivers do not get to wander inside the White House or Pentagon unescorted. They typically hand off the food at a guard post or entry lobby. IDs are checked (especially for Pentagon deliveries – drivers might need to show a driver’s license and have the delivery inspected). Payment is often handled by phone or a staffer will swipe a government card upon pickup to minimize contact. Some agencies even maintain a list of “approved vendors” who are allowed to deliver to the building after a quick screening. For example, the Pentagon’s Defense Protective Service might have a standing arrangement with known pizza joints, where drivers get a temporary pass to approach an entrance. At the White House, deliveries usually go to the northwest gate or another Secret Service entry, and a junior staffer is dispatched outside to bring the food in. The whole process can add a few minutes, but it’s remarkably routine – as long as the pizza guy arrives before it gets cold!

So how can an OSINT practitioner or curious journalist actually track pizza delivery spikes in real time? In the past, you’d need an army of informant pizza drivers or a stakeout across from Domino’s. Today, however, technology and open data have made it surprisingly feasible to watch these patterns remotely. Here are methods (both straightforward and creative) to keep tabs on the “Pentagon Pizza Meter” as it happens:

To put it in perspective, these methods parallel other pattern-of-life OSINT techniques. Just as satellite imagery analysis might count cars in the NSA parking lot to gauge activity, or flight trackers watch for late-night government jets, the Pizza Index monitoring uses civilians’ eyes and apps to infer government doings. It’s crowdsourced intelligence.

Of course, one must combine these with broader situational awareness. A pizza surge means “something’s up,” but not what. Analysts cross-reference it with news hints, military deployments, or foreign chatter to guess the event. Still, a live Pizza Index tracker, though quirky, could become part of an OSINT early warning system. Even the U.S. military is aware of this – there were reports that in the 1990s a training video on operational security humorously called this kind of signal “PIZZINT” (Pizza Intelligence), warning personnel that even pizza orders can tip off adversaries.

Before you start basing predictions of World War III on Domino’s sales, a reality check: the Pizza Index is far from foolproof. Like any indirect indicator, it can produce false positives, and there are ways it can be gamed or simply misinterpreted. Here are some key limitations and caveats to keep in mind:

Not Every Pizza Means War: Government offices order food for many reasons that have nothing to do with global crises. A spike in late-night orders could simply mean folks are working late on a domestic issue – e.g., a budget shutdown standoff, a lengthy State of the Union speech writing session, or even a holiday party that ran out of snacks. For instance, during big snowstorms in D.C., staff might stay overnight at agencies (to ensure continuity of operations) and thus order dinner en masse. Similarly, an election night or major political debate can have West Wing staff glued to screens, dialing up Papa John’s, with zero national security implications. The pizza surge in 1998 was because of impeachment drama, not a military strike. So context matters; analysts must discern why people are working late.

Regular Overtime vs Crisis: Some government operations run 24/7 ordinarily. The Pentagon’s National Military Command Center, for example, always has a night shift. Those folks ordering a few pizzas at 11 p.m. is normal and not a spike. The Pizza Index is about deviation from baseline – one needs to know what’s normal for a Tuesday night at the Pentagon versus a suspiciously large order volume. If a particular night is only slightly above normal, it might be noise. Distinguishing routine overtime (which often happens during, say, end-of-fiscal-year crunch or routine exercises) from extraordinary surges is tricky and requires historical data.

False Alarms and Coincidences: The internet loves a good pattern, and sometimes we see one where none exists. It’s possible to have a night of heavy pizza orders and nothing major happens afterward – perhaps it was a drill, or maybe even a sports event (imagine a bunch of Pentagon staff stayed late to watch the Army-Navy football game or NCAA March Madness – they might order pizza, but that’s not exactly an invasion). With the Pizza Index meme going viral, there have been instances of overinterpretation. One night in 2023 saw reports of “lots of delivery activity at Fort Myer,” causing Twitter speculation, which turned out to coincide with a base-wide family event (free pizza for soldiers’ families). In short, correlation does not equal causation – many factors can cause a one-off spike.

Deliberate Camouflage: If we civilians have figured this out, surely professionals have, too. There is speculation (and some anecdotal claims) that the Pentagon took steps to mask its late-night ordering after the pattern became famous. One unverified story suggests that once Domino’s Meeks went public in 1991 about the Gulf War orders, the Pentagon brass were not amused. Allegedly they instituted a policy to spread orders across multiple restaurants or use internal catering when preparing for classified ops. The idea: instead of one pizzeria getting 50 orders (causing a noticeable spike), five different eateries might each get 10. This would dilute the signal. However, former insiders dispute whether any formal policy like that truly exists. It might be more ad-hoc – e.g., sometimes they’ll order Chinese, sandwiches, and pizza all together to mix it up. There’s also the chance of intentional deception: one could imagine security folks ordering a bunch of pizzas on a quiet night just to throw off prying eyes (though wasting budget on decoy pizzas seems a stretch!). Still, the possibility of countermeasures means the savvy OSINT analyst shouldn’t rely on pizza alone; the “index” could be scrambled if leadership chooses to.

Alternate Food Choices: Another way the signal might weaken is simply by changing tastes. If decision-makers decide to avoid pizza for health or secrecy reasons and start ordering sushi or salads, an observer focusing only on pizzerias would miss it. The “Pizza Index” in principle includes all takeout, but it’s named for pizza due to tradition. Modern diets or younger staff might prefer other cuisines. So a true crisis foodie-watcher might need to track the Pad Thai Index or Burger Index too. (However, pizza remains the easiest large-group solution, so it likely isn’t going away as a late-night staple.)

Small-Scale Ops Don’t Register: It’s important to note that covert ops involving only a few principals wouldn’t trigger a wave of food orders. The most sensitive missions (e.g., the intel leading to the bin Laden raid) were known by a handful of people who could quietly arrange catering or skip meals. Those won’t show up in our OSINT radar. The Pizza Index is more useful for broad government mobilizations – when dozens of staff are in war rooms or command centers unexpectedly. A drone strike decision made by 5 people in a secure bunker won’t need 20 pizzas. So absence of a pizza spike doesn’t mean nothing is happening; it might just be tightly held.

Data and Access Gaps: Relying on third-party platforms like Google or Yelp for data is always fraught – they might change what they display, or the data might lag. And not every restaurant shares live info. Some key government cafeterias or on-site dining (like the White House Mess or Pentagon’s 24-hour canteen) are black boxes to us; if those are used instead of ordering out, we’d see nothing. Also, during actual emergencies (say a cyber attack taking down systems), delivery apps might not function normally anyway. So the method has blind spots.

In sum, the Pizza Index is a fascinating adjunct indicator, but it requires human judgment and context to use properly. False positives can and will happen. The meme-worthy nature of the idea means one has to be extra cautious to separate humor from actionable intel. It’s best employed alongside other OSINT and news sources. As Euronews wryly noted, “It’s hardly a reliable geopolitical indicator and no definitive correlation has been established. However, it remains a tasty predictor if so.” In other words, enjoy it as a clever insight, but don’t bet the farm (or the fleet) on pizza orders alone.

The rise of the Pizza Index raises some interesting ethical questions in the realm of open-source intelligence. On one hand, everything we’ve described uses publicly available data – no hacking, no privacy violations in theory. Checking Google Maps or reading Reddit posts about deliveries is legal and open. But there are still lines to be mindful of:

Legality of Open Data Analysis: Monitoring restaurant activity via open web sources is generally legal. It’s comparable to listening to police scanners or watching a public webcam. The data is aggregate and doesn’t identify private individuals. That said, if one attempted to get more specific data (like hacking into a pizza place’s order database or tracking individual drivers’ phones without consent), that would cross into illegality. OSINT investigators must stick to info that is truly public. Scraping a public website for busyness info? Likely fine. Placing a GPS tracker on a delivery car? Not fine.

Privacy of Individuals: Even though the Pizza Index deals with group behavior, there are people involved – the government employees working late and the delivery drivers. Ethically, one should avoid doing anything that doxxes or endangers individuals. For example, if an OSINT analyst actually identified a specific White House staffer always ordering from a certain place and tried to publicize or contact them, that would be unethical. Similarly, harassing delivery drivers for intel (“hey buddy, who are those 12 pizzas for?”) crosses a line into potentially unsafe territory for them. Analysts should aggregate and anonymize – we care about volume, not names.

Operational Security vs Public Right-to-Know: This is a classic tension. Some might argue that publicizing the Pizza Index could harm U.S. national security by prompting adversaries to monitor the same signals. (Rest assured, foreign intel services likely already do monitor anything monitorable – as noted, Soviets did it decades ago.) Still, if the Pentagon felt pizza surveillance was a serious threat, they might clamp down on staff ordering externally during sensitive times (at the extreme, maybe have on-site catering pre-stocked to remove the need). But doing so would hamper their own convenience – and as we’ve seen, even spooks like a good slice. From a public interest perspective, the Pizza Index is a fun example of transparency in action: even the mightiest institutions leave open-source breadcrumbs (or crusts) that an alert public can observe. Ethically, shining a light on this fosters accountability – it’s akin to noting when government motorcades suddenly rush off (another open cue something’s happening).

Misinformation and Panic: A real risk is misinterpretation leading to public panic or misinformation. Imagine someone on social media yells “The Pentagon ordered 100 pizzas, war with X is imminent!” – this could spread rumors or fear without basis. Responsible OSINT practice means not jumping to conclusions and clarifying uncertainty. Analysts and journalists should communicate Pizza Index findings carefully, perhaps as one data point among many, and avoid hyperbole. It’s all too easy for a meme to morph into a conspiracy theory. (One Quora user even asked if Wikipedia deleting the “Pizza Meter” article was itself a sign of impending war – a tongue-in-cheek but telling example of overreaction.)

Respecting Business & Platforms: There’s also the consideration of not abusing platforms. Using Google or delivery apps for data is fine within normal use, but if someone overloads an API or violates terms of service in scraping, it could raise issues. Additionally, drawing lots of unwanted attention to a small business (like mobs of people constantly calling Domino’s asking “busy tonight?”) could hurt their operation. Analysts should try to be non-intrusive – basically, lurk and observe, don’t interfere.

In summary, the Pizza Index sits in a fairly benign area of OSINT – it leverages mundane data and hurts no one if done right. But practitioners should uphold ethical OSINT guidelines: use open information, don’t target private individuals, and always add context before sounding alarm bells. It’s also a great case study to discuss with policymakers about how seemingly trivial data (pizza sales) can carry intelligence value. As the world becomes more data-rich, behavioral indicators like this will multiply – raising new ethical lines about what is fair game to monitor. Today it’s pizzas; tomorrow it might be rideshare destinations or Netflix activity at government sites. The principle remains: open data is powerful, and with great power comes great responsibility (and maybe a side of breadsticks).

The “Pentagon and White House Pizza Index” is a striking example of how open-source intelligence can emerge from the unlikeliest of sources. What started as a Domino’s anecdote during the Cold War has evolved into a modern OSINT puzzle piece – one that mixes equal parts serious insight and cultural satire. On one level, it’s almost irreverent (Wired joking about pepperoni predicting war, or meme pages tracking pizza deliveries like weather reports). On another level, it speaks to a deeper truth: in our interconnected age, indirect signals are everywhere, even in the cheese pulls of a late-night pizza.

For analysts, journalists, and national security enthusiasts, the Pizza Index is a reminder to think outside the box (or pizza box) when assessing patterns. It broadens the concept of intelligence to include everyday logistics – a true “you are what you eat” moment for the security state. It also adds a bit of humanity to the spy game: behind those pizza orders are real people, working stressful, critical jobs, who get hungry and tired like the rest of us. The Pizza Index humanizes crisis anticipation – we can picture the scene of grim-faced officials in shirt-sleeves, ties loosened, crowding around a stack of Papa John’s as history unfolds in real time.

Will pizzas predict military strikes with 100% accuracy? No – and anyone reading this should temper their expectations. But as part of a holistic OSINT approach, watching those DC late-night food deliveries can provide a valuable early nudge that “something big is going down.” It’s one more tool in the ever-expanding toolbox of behavioral indicators, where national security food patterns meet networked information.

In the end, the Pizza Index also carries a subtle critique: it highlights how much of government activity can be observed through open means. In a way, it holds leaders accountable – you can’t easily hide preparation for war when dozens of staff must scramble and their dinner shows up in public data. It’s a small transparency in a big opaque system.

So, next time you’re doom-scrolling and see an image of a crowded pizza parlor near the Pentagon trending, you might rightly wonder: is the world about to change overnight? Maybe it’s a false alarm… or maybe it’s the calm before the storm, marked by extra-large pies. Only time (and perhaps a few well-placed delivery receipts) will tell. Until then, keep your eyes on the ovens and remember: sometimes the biggest secrets come with a side of marinara.