Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

On 19 September 2025, Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) announced Silent Courier, a secure messaging portal on the Tor network that allows people anywhere in the world to anonymously contact MI6 with information on terrorism, illicit activity or hostile-state intelligence. The British Foreign Office explained that the portal harnesses the anonymity of the dark web and will enable MI6 to recruit new agents globally; instructions for accessing it appear on MI6’s verified YouTube channel. Outgoing MI6 chief Sir Richard Moore declared that their “virtual door is open” and asked individuals with sensitive information to contact the service. Home Secretary Yvette Cooper framed the move as part of a generational uplift in national defence spending and argued that the UK must stay ahead of adversaries by using cutting‑edge technologies. Media reports from Reuters, Al Jazeera, Sky News and others highlighted the novelty of a Western intelligence service embracing the dark web—a part of the internet reachable via the Tor network where anonymity is increased through onion routing. Journalists noted that the initiative targets Russian insiders but is open to anyone wishing to offer their services.

MI6’s Silent Courier is both headline‑grabbing and historically significant. Traditional espionage has often relied on personal connections, embassy walk‑ins, and clandestine meetings in shadowy locations. By moving recruitment into the digital shadows, MI6 signals an evolution of human intelligence (HUMINT) tradecraft in response to pervasive digital surveillance and shrinking freedom for would‑be informants. For whistleblowers and dissidents, the portal offers a high‑stakes channel to pass information while minimizing the risk of attribution. For intelligence practitioners and OSINT analysts, it provides a unique case study in how agencies are adopting dark‑web technologies to manage sources. This analysis piece will:

For most of its history, MI6 and its counterparts (CIA, KGB/SVR, MSS, etc.) relied on face‑to‑face recruitment. Agencies cultivated sources through personal relationships, diplomatic contacts, or walk‑ins—voluntary approaches at embassies or safehouses. During the Cold War, clandestine meetings took place in hotels, parks or diplomatic premises; “dangle” operations were used, where an individual would pretend to defect in order to bait an adversary into recruitmentgreydynamics.com. Double agents fed adversaries with selective information while remaining loyal to their own services. In this era, verifying the authenticity of a source involved physical surveillance, polygraphs, and modus operandi tradecraft.

By the late 20th century, intelligence agencies began providing encrypted tip lines. Phone hotlines allowed anonymous reports of suspicious activities. The United States’ FBI and Canada’s CSIS created websites for submitting leads, though these often collected identifying metadata, potentially deterring sensitive whistleblowers.

The rapid adoption of the internet—and later, social media—reshaped HUMINT. Dissidents, criminals and extremists increasingly communicate online, leaving digital traces. Open‑source intelligence (OSINT) practices matured as analysts learned to harvest publicly available information from social media, forums, geospatial data and government records. Social media intelligence (SOCMINT) became integral to identifying networks and assessing narratives. However, digital surveillance by authoritarian governments complicated recruitment: unencrypted email or messaging could easily be monitored.

Recognizing these challenges, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) pioneered dark‑web recruitment. In May 2019 the CIA launched a .onion website on the Tor network that replicated its public site and provided detailed instructions on how to contact the agency securely. The CIA emphasised that Tor hides a user’s location by bouncing traffic through multiple relays and recommended that informants use a trusted VPN and a device not registered to them. In 2023 the CIA released Russian‑language videos on social media appealing to “patriotic Russians” who felt betrayed by corruption; the videos described ways to contact the CIA via encrypted channels. These initiatives signalled that Western intelligence services saw digital anonymity as essential to future recruitment.

MI6 has also gradually embraced digital outreach. In 2021 the service launched an Instagram account, mixing branding with recruitment. A communications researcher noted that MI6’s social media strategy blended entertainment, branding and politics to improve public understanding and attract potential recruitsobserver.co.uk. However, until Silent Courier, MI6 had not provided an official dark‑web channel for informants.

The dark web refers to websites that are not indexed by search engines and are accessible only via protocols like Tor (The Onion Router). Tor encrypts traffic through multiple hops, with each node decrypting only the previous layer (hence the “onion” metaphor). This structure provides anonymity by obscuring users’ locations and prevents a single operator from linking sender and receiver. However, the dark web is also home to illicit marketplaces, malware hosting and criminal forums. Law enforcement operations like Operation Onymous (2014) exposed vulnerabilities in hidden services. The Tor Project later speculated that undercover agents infiltrated some websites, operators committed operational‑security errors, and network‑level attacks (e.g., SQL injections or guard‑node deanonymisation attacks) were used to locate servers. Hundreds of hidden services were seized, demonstrating that anonymity is not absolute; flawed websites, compromised relays or Bitcoin deanonymisation can expose operators. The dark web thus offers both security and risk; it provides a channel where governments can recruit sources but also a battlefield where adversaries and law enforcement attempt to deanonymize one another.

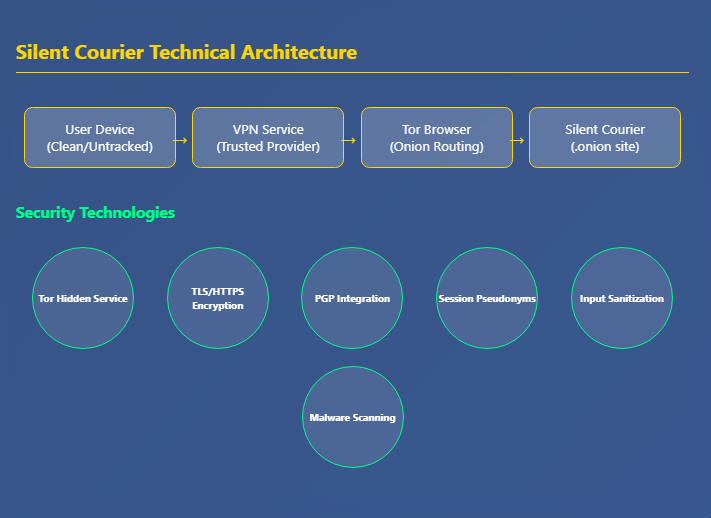

The UK government’s press release describes Silent Courier as a “secure messaging platform” on the dark web that harnesses anonymity. The portal allows anyone with information on terrorism, global instability or hostile intelligence activity to contact MI6 and offer their services. The announcement emphasises that instructions on how to access the portal are publicly available on MI6’s verified YouTube channel, and it urges users to employ trustworthy VPNs and devices not linked to them to mitigate risk. In a promotional video, MI6 acknowledges that its traditional bedrock has been face‑to‑face meetings but that it is now embracing dark‑web anonymity to reach sources worldwide. Reuters reports that the portal will be formally unveiled in Istanbul by Sir Richard Moore, who describes it as a way for individuals to securely pass details about illicit activities or offer their services. The service appears to be an onion site accessed via Tor; its full address is typically provided through official channels.

MI6’s public guidance, like that of the CIA, emphasises operational security (OPSEC). Would‑be informants are instructed to use a clean device (a computer or phone not connected to their identity), run the Tor browser, connect through a reputable VPN to conceal their initial IP address, and avoid using personal networks. MI6 also notes that individuals should not share the portal address outside of the official channel to reduce exposure. Because the portal is a one‑way intake system, MI6 presumably responds through separate channels or provides a pseudonym for follow‑up; details remain classified.

Given precedent from CIA’s onion site and from SecureDrop (an open‑source whistleblower submission system used by media organizations), Silent Courier likely employs several technical measures:

A key challenge for a dark‑web recruitment portal is validating information from an anonymous source without deanonymizing them. Intelligence services must balance security with vetting, because adversaries can flood portals with disinformation, malware or entrapment. Without physical meetings, verifying a source’s identity requires alternative indicators:

The ShadowDragon OSINT challenge report notes that verifying open‑source data often requires cross‑reference across multiple sources and careful evaluation of credibilityshadowdragon.io. For dark‑web tips, this cross‑reference may involve internal intelligence holdings rather than open sources. Ultimately, authenticity cannot be guaranteed; every lead is treated with suspicion until corroborated.

| Platform | Anonymity Level | Target Audience | Technical Innovation | Operational Risk | Public Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI6 Silent Courier | Very High | State-level informants | YouTube integration | High (counterintel) | High visibility launch |

| CIA Onion Portal | Very High | Global intelligence sources | First agency adoption | Medium-High | Moderate visibility |

| SVR Tor Platform | High | Western assets | Keyphrase system | Medium | Very low profile |

| SecureDrop | Very High | Media whistleblowers | Open source model | Low-Medium | Transparent operation |

| FBI Tip Line | Low | General public | Traditional approach | Low | Public service focus |

While Tor provides anonymity, hidden services are not invulnerable. The Tor Project’s reflection on Operation Onymous lists several plausible ways law enforcement located hidden services: operational‑security failures, infiltration by undercover agents, exploitation of web application bugs (e.g., SQL injections), Bitcoin transaction deanonymisation, and network‑level attacks like the guard discovery attack. Silent Courier must defend against these vectors:

In short, Silent Courier’s design must strike a balance between ease of use for informants and robust security against infiltration and deanonymisation.

Silent Courier may attract not only genuine informants but also adversarial intelligence agencies such as Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS), Iran’s MOIS and North Korea’s Reconnaissance General Bureau. These services may attempt to:

SecureDrop, used by media organizations and NGOs, offers an instructive comparison. Its documentation notes that the system does not log IP addresses, encrypts all data, and uses open‑source code. However, it requires skilled administrators and constant audits to ensure that vulnerabilities are patched. When the Russian SVR quietly launched its own Tor tip platform, it generated a unique five‑word key phrase for each source to access later. The low‑profile release suggests that adversaries might adopt similar systems without public fanfare.

Law enforcement has also recognized the utility of Tor. A 2015 VICE article described how a security researcher created a dark‑net replica of the FBI tip line to demonstrate that law enforcement could use hidden services to accept anonymous tips, which might increase informant comfort and reduce the collection of identifying informationvice.com. In addition, the U.S. Operation Onymous dismantled hundreds of Tor marketplaces, showing that state actors are capable of penetrating hidden services using infiltration, exploitation and traffic analysis.

These experiences suggest that Silent Courier will face a cat‑and‑mouse dynamic. MI6 can benefit from the dark web’s anonymity but must anticipate adversaries using the same domain to detect, manipulate or subvert the portal. Rigorous counter‑intelligence—monitoring submissions for deception, cross‑checking with other sources, and isolating the system from MI6 networks—will be critical.

OSINT practitioners—journalists, researchers, private intelligence firms—use publicly available information to understand actors and detect trends. Silent Courier’s existence will likely spark chatter on forums, Telegram channels and social media. OSINT analysts can monitor these conversations to assess interest, misinformation campaigns or efforts to spoof the portal. However, caution is necessary. The dark web is deliberately unindexed and often requires manual navigation; many forums are invitation‑only. Tools that crawl dark‑web marketplaces exist, but they risk crossing legal boundaries.

The ShadowDragon report outlines a major challenge for OSINT investigators: verifying the accuracy and reliability of open‑source data. Investigators must cross‑reference multiple sources, check consistency and identify biases. When dealing with dark‑web data, the report notes that information is fragmented, unindexed, and intentionally deceptive; attribution is unreliable by design. Analysts should examine language patterns, timestamps and metadata and recognise that many posts are raw, high‑risk and intentionally misleading.

Silent Courier complicates source validation. Because MI6 might act on information from an anonymous portal, OSINT researchers may only learn about successful leads years later, if at all. Still, they can watch for indirect indicators: arrests, policy changes or diplomatic expulsions that follow dark‑web chatter. Researchers can also track whether adversaries attempt to phish potential informants by advertising fake portals.

The proliferation of digital tip lines normalises digital HUMINT—the practice of collecting human intelligence through digital, often anonymous channels. This trend intersects with OSINT because the same technologies (VPNs, Tor, encryption) are used by activists, journalists, criminals and spies. OSINT analysts must therefore understand the technical underpinnings of onion services, encryption, and OPSEC. The CIA’s onion site provides educational resources on how Tor works and emphasises that anonymity is not absolute; similar guidance informs OSINT practitioners about the limitations of anonymity networks. Analysts should also familiarise themselves with PGP and encryption protocols to verify authenticity of leaks and protect their communications.

MI6’s adoption of a dark‑web portal may inspire non‑governmental organisations (NGOs), journalists and private OSINT firms to adopt similar secure intake methods. News outlets like The Guardian have long used SecureDrop for whistleblowers; they can examine MI6’s model to enhance their own systems. Private firms may develop custom onion services for corporate whistleblowing or supply‑chain intelligence. However, as the ShadowDragon report emphasises, investigators need not only technology but also structured methodologies to filter information, mitigate biases and ensure legal compliance. Implementing dark‑web intake requires robust governance policies, legal review and staff training on OPSEC.

Finally, OSINT practitioners can play a role in oversight. Intelligence agencies operating on the dark web introduce new privacy risks, but secrecy may preclude formal public scrutiny. OSINT analysts can document the existence of such portals, track their official addresses, report spoofed versions, and educate potential users on safe practices. This “watchdog” role is critical to ensure that dark‑web recruitment does not become a magnet for entrapment or exploitation.

The dark web conjures images of anonymity, but its legal status is ambiguous. In many jurisdictions, merely visiting onion sites is not illegal; however, connecting to a government spy agency’s portal may draw attention if surveillance is being conducted. Individuals who discover Silent Courier out of curiosity risk being misinterpreted by their own governments or by MI6. Furthermore, the portal’s guidelines encourage using VPNs and devices not tied to users, which may not be feasible for all. Mistakes—using a personal phone, copying the address into a regular browser, or sharing the link—could expose the user.

For Silent Courier to operate responsibly, MI6 must implement strong governance and oversight mechanisms. These may include:

MI6’s launch of Silent Courier highlights ongoing dynamics in the evolution of human intelligence. It reflects a world where physical meetings are risky, digital footprints ubiquitous, and intelligence agencies must adapt to recruit sources and gather information. By embracing the dark web, MI6 demonstrates that digital HUMINT is now mainstream. The portal will likely shape recruitment dynamics by providing an accessible channel for insiders in hostile states or organisations, particularly in Russia. Its significance also lies in legitimising the dark web as a tool for statecraft, challenging narratives that cast it solely as a criminal haven.

However, the portal raises significant risks. Hidden services can be compromised through infiltration, exploitation or traffic analysis. Adversaries can flood the portal with dangles or disinformation. Ordinary citizens may be harmed if they miscalculate operational security. The ethical line between offering a secure channel to whistleblowers and encouraging treason is blurred. Effective counter‑intelligence, robust technical security, transparent guidance and legal oversight will determine whether Silent Courier becomes a boon or a liability.

Looking ahead, we can anticipate copycat portals. Other intelligence services—both democratic and authoritarian—may establish dark‑web recruitment platforms. Private corporations and NGOs might adopt similar systems for whistleblowing or supply‑chain intelligence. Meanwhile, adversaries will innovate infiltration techniques, leading to an arms race in anonymous recruitment.

For OSINT practitioners, Silent Courier is both a research topic and a potential cautionary tale. Analysts should monitor the dark‑web ecosystem for chatter, spoofed portals and disinformation campaigns. They must refine their understanding of onion routing, encryption and operational security to keep pace with digital HUMINT. At the same time, they should uphold ethical standards by educating the public about risks and by maintaining scepticism toward anonymous tips. In an era where secrecy and transparency collide, Silent Courier symbolises the ever‑shifting boundaries of espionage—boundaries that OSINT analysts are uniquely positioned to observe, document and interrogate because of their position outside the mainstream system.