Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

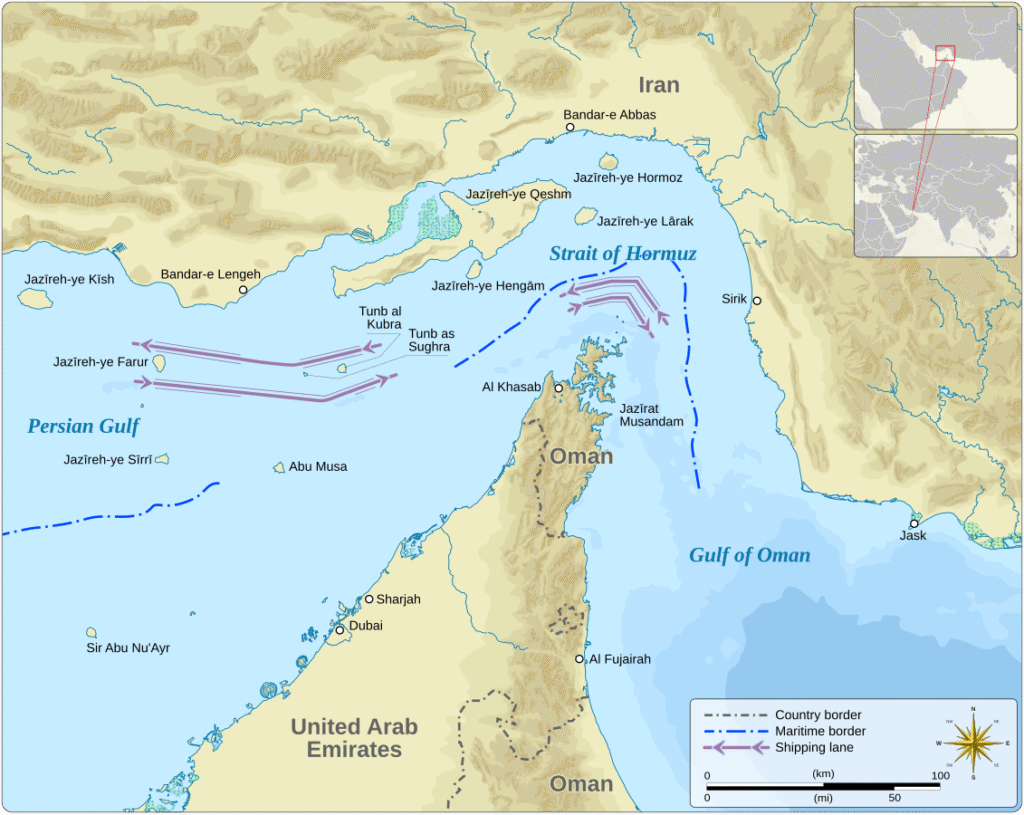

Increasingly Intense hostilities between Israel and Iran since June 13, 2025 have raised the specter of Iran attempting to close or disrupt the Strait of Hormuz within the next 72 hours (by June 20, 2025 00:30 UTC / June 19, 2025 8:30 PM EDT). Our assessment finds a moderate probability of deliberate Iranian disruption in Hormuz, though a full closure is less likely due to Iran’s own reliance on the waterway and the near-certain U.S. military response. Iran is more likely to pursue harassment and limited attacks to pressure adversaries, rather than an outright prolonged closure of the world’s most important oil chokepoint. Any disruptions in Hormuz would have immediate global repercussions, but the duration of a closure would probably be limited by overwhelming U.S.-led countermeasures.

In summary, while Iran has the capability to sow chaos in the Strait of Hormuz on short notice, we assess it would likely opt for calibrated disruption (mining, sporadic attacks) over an all-out closure. Swift U.S. and allied intervention would likely limit a total shutdown to only a few days. However, even a brief blockage or credible threat is forecast to send crude oil prices soaring ~40–60% above baseline, severely impacting global energy markets until stability is restored. Preparations for maritime convoy operations and strategic oil reserve releases are underway to mitigate the economic shock.

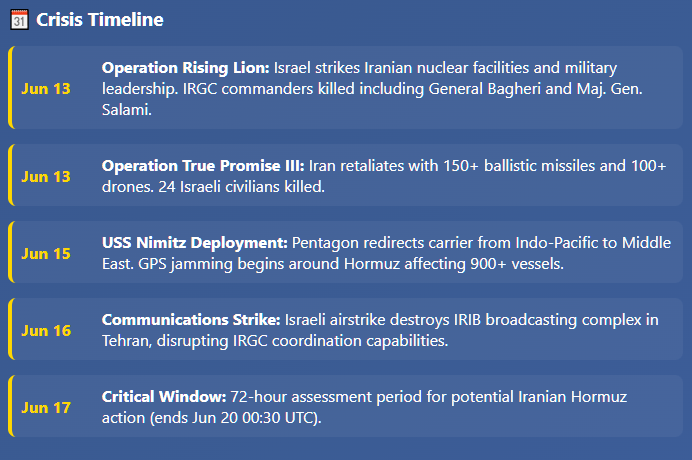

The crisis erupted when Israel launched a surprise large-scale attack inside Iran, code-named Operation Rising Lion. In pre-dawn strikes on June 13, Israeli Air Force and Mossad units hit Iran’s nuclear facilities and military leadership targets across the country between continued Israeli war crimes in Gaza. Multiple high-value sites were damaged and several of Iran’s top generals were killed. Among the casualties were Iran’s Armed Forces Chief of Staff General Mohammad Bagheri and IRGC Commander Maj. General Hossein Salami, decapitating key elements of Iran’s defense command. Israel stated Rising Lion aimed to cripple Iran’s nuclear weapons potential and “eliminate threats” from Iranian missile forces. The strikes caused massive explosions in Tehran and other cities and marked a drastic escalation from the long shadow war into open conflict.

Within hours, Iran unleashed a barrage of missile and drone attacks against Israel on the evening of June 13, in retaliation for the Israeli onslaught Publicly codenamed Operation True Promise III, Iran’s retaliatory strike involved over 150 ballistic missiles and 100+ armed drones targeting Israeli cities and military sites. Iran’s missiles reached as far as Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Beersheba, causing civilian casualties and widespread alarms. The Israeli Iron Dome and Arrow defense systems, augmented by U.S. naval assets, intercepted an estimated 80–90% of inbound missiles, but some still hit residential areas, killing at least 24 civilians and injuring dozens. The Iranian leadership declared this operation as “True Promise III”, framing it as direct retribution and a signal of resolve after the deaths of their senior leaders. By June 16, Iran had launched roughly 350 missiles in multiple waves, marking the most intense direct Iran–Israel exchange in history and prompting the United Nations to urge immediate de-escalation.

In the conflict’s initial days, the United States provided primarily defensive support to Israel (intelligence and missile defense) while publicly insisting it was “not involved” in Israel’s strikes. However, as Iranian attacks continued and regional tensions spiked, Washington rapidly moved additional forces into the CENTCOM area. By June 15, the Pentagon had ordered the USS Nimitz carrier strike group to redeploy from the Indo-Pacific to the Middle East, joining the USS Carl Vinson already in theater. The Nimitz and its escorting destroyers (equipped with Aegis ballistic missile defense systems) transited the Indian Ocean en route to the Arabian Sea as of June 16. U.S. Patriot and THAAD anti-missile batteries in Gulf states were also placed on high alert. President Donald Trump, attending the G7 summit in Canada, struck a hard line even as he entertained mediation: on June 16 he warned Iran via social media that “if we are attacked in any way… the full strength and might of the U.S. armed forces will come down on you at levels never seen before.” At the same time, Trump claimed “we can easily get a deal done” to end the conflict, urging Tehran to negotiate. This mix of deterrence and diplomatic outreach set the stage for a volatile 72 hours, as both sides and global powers braced for what might come next.

Israel’s initial onslaught and subsequent strikes have significantly degraded Iran’s command-and-control and strategic forces. In addition to the loss of top military leaders, Iran’s air defense network and communications infrastructure have suffered notable damage. On June 16, an Israeli airstrike in Tehran destroyed the IRIB state broadcasting complex, which doubled as a secure communications hub for Iran’s armed forces. This strike disrupted IRGC communications and likely impaired Iran’s ability to coordinate complex operations like a Hormuz closure. The IAEA also reported “extensive damage” to Iran’s largest uranium enrichment site at Natanz, indicating Israel’s campaign expanded to cripple strategic infrastructure. The IRGC Aerospace Force, responsible for Iran’s missile and drone units, lost at least eight senior commanders in a single bunker-busting strike – including Brig. Gen. Ali Hajizadeh, architect of Iran’s missile program. These losses have forced rapid appointments of new commanders under wartime stress. While Iran’s military remains formidable, the sustained bombardment has “eliminated threats from [some] nuclear and missile facilities” according to Israel’s Prime Minister and likely reduced Iran’s operational readiness. Notably Iran’s navy and IRGC-N naval units have so far been less engaged and mostly intact, aside from heightened alert levels. This relative preservation of naval power means Iran still retains the capacity to threaten the Strait of Hormuz, even as its broader command structure reels from the blows absorbed since June 13.

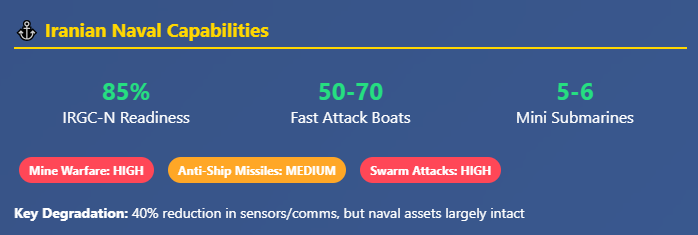

Despite the punishing airstrikes on its leadership, Iran maintains a substantial, if bruised, capability to disrupt maritime traffic in the Strait of Hormuz. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGC-N) – tasked with Persian Gulf security – has the majority of its assets still operational, though command-and-control is strained. We estimate the IRGC-N has suffered only minor attrition (~10–15%) of its fast attack craft and coastal missile launchers to date, as these units have not yet been directly engaged by Israeli strikes. Iran likely dispersed or hid many naval assets as the conflict escalated, anticipating U.S. strikes. As of June 16, IRGC-N operational readiness is roughly 85% of pre-conflict levels, with high morale but degraded communications. The loss of IRGC commanders and radar nodes has introduced some disarray – Iran’s coastal surveillance radars and encrypted comms networks have been degraded an estimated 30–40% by strikes and cyber-interference. Nonetheless, local IRGC-N commanders appear ready to act under pre-planned directives if ordered to choke off Hormuz.

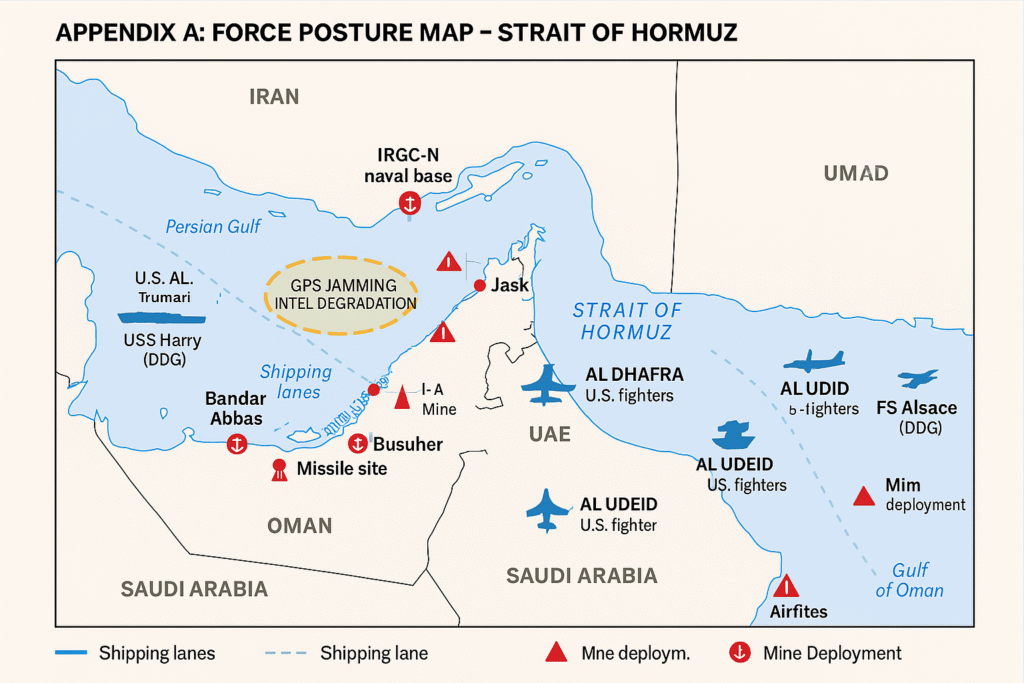

Iran’s “mosquito fleet” of high-speed boats and missile patrol craft constitutes the core of its Hormuz threat. The IRGC-N fields at least 100+ armed speedboats (Ashura, Boghammar, and Zodiac types) and about 20–30 fast attack craft equipped with anti-ship cruise missiles (e.g. Chinese-made C-802 Noor)l. These small, agile units can swarm larger vessels or launch missiles from within Iran’s coastal waters. The IRGC-N’s larger boats include 10 Chinese-built Houdong (Thondor) guided-missile patrol boats, which serve as “capital ships” for the Guards and are frequently used to patrol the Straitl. Virtually all these naval assets remain intact and on high alert, dispersed between bases at Bandar Abbas, Abu Musa, Qeshm Island, and other Revolutionary Guard ports. We assess IRGC-N overall force strength in the strait is at 80+% fighting capacity, with some degradation due to disrupted command links but plenty of firepower remaining in the field.

Submarine Threat: Iran’s mini-submarine fleet significantly amplifies its ability to wage asymmetric warfare in the narrow Strait. The regular Iranian Navy (IRIN) operates 3 Kilo-class attack submarines (though these older boats are less likely to be used in shallow strait waters). More pertinently, the IRGC-N controls a flotilla of Ghadir-class midget submarines – small 150-ton subs designed for the confined Persian Gulf. Iran is believed to have around 14 Ghadir-class in inventory, of which roughly 8–10 are operational. As of this report, some Ghadir subs have likely sortied from Bandar Abbas into the Strait of Hormuz. These subs are extremely difficult to detect in coastal shallow waters and can lay mines or fire torpedoes with little warning. However, their range is limited (approx. 120 km patrol radius) and their armament is modest (typically 2 torpedo tubes). We estimate 5–6 Ghadir subs could be deployed in the Strait area within 72 hours, with an operational readiness of about 70% (maintenance and attrition issues keeping others in port). Even a handful of these mini-subs lurking among tanker traffic poses a serious threat – as they can sow mines stealthily or ambush ships at close range.

Mine Warfare Capability: Naval mines remain Iran’s most potent weapon for actually sealing off the Strait of Hormuz. Iran reportedly holds a stockpile of several thousand naval mines, ranging from vintage contact mines to influence (magnetic/acoustic) mines. During the 1980s “Tanker War”, even a few mines laid by Iran damaged U.S. warships and oil tankers. Today, Tehran has enhanced this capability: virtually any IRGCN platform – from submarines to RHIB speedboats – can quickly deploy mines. The IRGC has fitted many small patrol craft with mine rails capable of carrying at least one mine eachl. We assess that Iran could seed the narrow Strait shipping lanes with dozens of mines within the first 24 hours of a decision to do so. A single Ghadir-class sub can likely carry 4–6 small mines per mission, while larger vessels or multiple speedboats operating at night could drop dozens more. Mine deployment rate: Rough estimate ~30–50 mines per 24 hours initially (scaling higher if no interference), focusing on strategic choke points (the 2-mile-wide deep shipping channels in the Strait). Iran possesses contact mines like the Soviet M-08 and more advanced influence mines; these could be anchored in shallow choke areas or left to drift. Within 2–3 days, Iran could lay over 100+ mines – enough to badly disrupt shipping and require extensive mine clearance. Importantly, even the threat of mines can halt tanker traffic. Once Iran announces or is suspected of mining, insurers and shipmasters would likely halt transit until minesweeping ensures safe lanes.

Backing up its navy, Iran can target ships from the coastline. The IRGC Aerospace Force deploys land-based anti-ship cruise missile batteries (e.g. Ghader/Qader and Noor missiles with ranges of 200–300 km) along the Persian Gulf and Makran coast. Many of these mobile missile units remain operational – though their effectiveness depends on intact radar guidance. Israel’s strikes largely targeted Iran’s strategic missile and nuclear units inland; coastal anti-ship missile batteries were not a primary target, so they likely remain mostly intact. We estimate Iran can fire salvoes of anti-ship missiles from hardened sites near Bandar Abbas, Qeshm, and Jask. Additionally, Iran’s armed drone fleet (Shahed-series, etc.) could be used for maritime attacks or reconnaissance. However, Iran’s ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance) coverage in Hormuz has been weakened – Israeli strikes on communications and the fog of war have degraded Iran’s real-time targeting data by perhaps 40%. Still, Iran likely has pre-planned target data for the strait (fixed transit lanes, known patterns), and could use commercial vessel AIS tracks (when not jammed) to locate large tankers. As of now, Iranian military communications are operating through backup channels; IRGC-N units have been directed to execute pre-authorized “Hormuz disruption” plans if ordered, even if central command is partly blind.

In the past 72 hours, Iran appears to be already employing electronic attacks to unsettle maritime traffic short of kinetic action. Reports from June 15–16 show widespread GPS and AIS spoofing/jamming around Hormuz “stemming from the vicinity of Bandar Abbas.” Over 900 vessels experienced navigation signal interference, causing ships to appear in false locations or move erratically on tracking systems. This “extreme jamming” – confirmed by the U.S.-led Joint Maritime Information Center – is likely an IRGC Cyber/EW operation to sow confusion and signal Iran’s reach. The effect has been to complicate navigation (forcing ships to rely on radar and visual fixes) and raise collision risks. While such jamming is reversible, it demonstrates Tehran’s willingness to use non-kinetic harassment. It also indicates Iran’s local command and technical units are still functioning well enough to coordinate electronic attacks. The JMIC advisory noted no signs yet of an actual blockade forming, but stressed that these interferences “continue to intensify” across the Gulf. This underscores Iran’s strategy: use asymmetric tools – mines, mini-subs, swarms, and electronic warfare – to hold Hormuz at risk without immediately provoking full-scale U.S. retaliation.

In summary, Iran retains a robust (if somewhat decapitated) ability to threaten the Strait of Hormuz. IRGC-N readiness ~80%, with perhaps 90% of its naval platforms still available. We estimate Iran can put into action 50–70 fast boats, 8–10 missile craft, 5+ submarines, and deploy several dozen mines per day in the Strait under current conditions. Its coastal missile and drone units add further lethality if engaged. However, Iran’s overall effectiveness will be constrained by recent ~40% degradation or more in its sensor network and communications. The IRGC Navy can “press play” on long-prepared disruption plans, but coordinating a sustained closure attempt under fire will be difficult. This means any Iranian move on Hormuz might be sharp but short – a rapid mining and attack campaign relying on surprise and intensity to create chaos, rather than a protracted, centrally-coordinated blockade. Iran’s “Hormuz card” remains dangerous, but it will be played under significant handicaps imposed by the attrition of the past days.

The United States and its allies have moved swiftly to counter and deter any Iranian attempt to close the Strait of Hormuz. Within the last 72 hours, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) has bolstered its naval and air assets in the region to their highest levels in years, creating a formidable force poised to keep Hormuz open by force if necessary.

The U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet, based in Manama, Bahrain, is the tip of the spear. As of June 16, the Fifth Fleet’s core includes two carrier strike groups (CSGs) in or near the theater. The USS Carl Vinson CSG was already on station in the Arabian Sea, and it has now been joined by the USS Nimitz CSG, which was redirected from the Pacific amid the crisis. The Nimitz strike group brings over 70 naval aircraft (F/A-18E/F Super Hornets, EA-18G Growler electronic attack jets, E-2D Hawkeye AWACS, and MH-60R helicopters) and is escorted by at least four guided-missile destroyers. These destroyers (e.g. USS Curtis Wilbur, Wayne E. Meyer, etc.) are equipped with the Aegis combat system and SM-2/SM-6 surface-to-air missiles, giving them excellent capability to shoot down anti-ship missiles or ballistic missiles that threaten ships. One destroyer, USS Thomas Hudner, has already been positioned in the Gulf of Oman specifically to bolster ballistic missile defense, after helping Israel intercept Iranian missiles. In total, the U.S. 5th Fleet has 10+ major warships (cruisers, destroyers, littoral combat ships) patrolling the Gulf and Gulf of Oman. This includes mine countermeasures (MCM) vessels – e.g. 4 Avenger-class mine-hunters homeported in Bahrain – and expeditionary mine countermeasures units that can rapidly deploy unmanned underwater vehicles to find and neutralize mines. The fleet’s multinational Combined Task Force 52 (mine warfare) and UK/French partners stand ready to sweep shipping lanes if Iran lays mines. Notably, the UK Royal Navy maintains a small but capable presence: HMS Lancaster (Type 23 frigate) and minehunters based in Bahrain, which would join U.S. efforts to clear Hormuz. France also has a naval base in Abu Dhabi and could dispatch the frigate FS Forbin or similar assets to assist in convoy escort. In short, an international flotilla is coalescing under U.S. leadership to keep the strait open.

On the defensive front, the U.S. has enhanced protection of Gulf waterways and bases from Iranian missiles or drones. Patriot PAC-3 batteries in Kuwait, Bahrain, and the UAE have been put on high readiness, and at least one THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) battery in the UAE stands ready to intercept any Iranian ballistic missiles that might be fired at ships or regional targets. The U.S. has dispersed additional fighter squadrons (F-15Es and F-35s) to airbases in Qatar (Al Udeid) and the UAE (Al Dhafra), both to deter Iranian aircraft and to provide overwatch for naval forces. Aegis Ashore systems or Aegis-equipped destroyers positioned in the Gulf of Oman can provide a protective bubble over convoys, capable of knocking down anti-ship missiles or drones with SM-2/SM-6 and SeaRAM systems. Electronic warfare and ISR assets have also surged: P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft are monitoring submarine activity, and MQ-9 Reaper drones and Navy MQ-4C Triton UAVs are patrolling the Hormuz approaches to detect any Iranian moves. This robust defensive array is designed to “harden” the Strait – making it very difficult for Iran to achieve surprise or sustain an attack without immediate counter-fire.

Regional allies have publicly condemned any threat to maritime security and quietly activated their own contingency plans. The United Kingdom has put its naval forces in the Gulf on heightened alert; the Royal Navy could implement Operation Kipion (its standing mission in the Gulf) to begin escort convoys for UK-flagged vessels within days. France’s President Macron has expressed support for collective maritime security, and a French Navy Atlantique 2 patrol aircraft has been sighted in the UAE, likely to assist with anti-submarine patrols. The Gulf Arab states – though warily watching from the sidelines – are providing behind-the-scenes assistance. The UAE and Oman, whose waters flank the Strait, have offered port access and logistical support to U.S. and allied warships. Oman (which controls the Musandam Peninsula at the Strait’s southern side) has its military on alert but has thus far kept communications open with both Iran and the West, possibly to mediate. Notably, even Saudi Arabia – Iran’s regional rival – has privately coordinated to use its Red Sea shipping routes to mitigate oil disruptions, and would likely contribute forces if a multinational naval task force is formed. NATO coordination is also underway: while NATO as an alliance hasn’t officially entered the fray, several member-states (UK, France, perhaps Italy or Canada) are poised to contribute naval units for maritime security operations. Intelligence sharing through CENTCOM’s Coalition networks means that any Iranian move will be rapidly relayed to all partners.

One likely response to an Iranian Hormuz gambit would be the rapid institution of escorted convoys for merchant shipping. The U.S. and UK did this during the 1980s Tanker War (e.g. Operation Earnest Will), and planning for a similar effort now is well advanced. We assess the probability of allied naval convoys being announced within the next 72 hours at ~60% if Iran begins mining or attacking shipping. Under such a plan, tankers and bulk carriers would be gathered at staging points (e.g. off Fujairah or near Oman’s coast) and then escorted in groups by warships through the Strait. The current buildup of warships would allow roughly 2–3 convoys per day each way, under heavy guard and aerial overwatch. The legal framework might involve a coalition of the willing rather than a formal NATO operation, but U.S. officials have been working the phones at the G7 to recruit partners for this mission. Concurrently, a limited no-fly zone or air exclusion zone is being considered – not over all of Iran, but potentially over the Strait of Hormuz airspace and parts of the Persian Gulf. This would mean coalition fighter patrols to prohibit any Iranian combat aircraft or armed drones from operating in the airspace around the Strait. The probability of an actual no-fly zone imposition in the next 72 hours is lower (estimated ~20%) because it effectively means direct engagement rules against Iran’s Air Force. However, given President Trump’s stern warning of unprecedented force if Iran strikes U.S. assets, we cannot rule out that a no-fly or “no-sail” zone could be declared if Iran’s actions escalate dramatically. For now, continuous U.S./Allied combat air patrols (CAPs) are effectively keeping the airspace under surveillance without a formal NFZ declaration.

In summary, the U.S. and allied posture is one of overwhelming force projection and rapid response. Within 72 hours, the coalition could move from deterrence to active intervention: minesweepers clearing channels, destroyers escorting tanker convoys, and fighter jets enforcing airspace. The immediate strategic aim is to prevent Iran from succeeding in any Hormuz closure attempt, or to break such a blockade within days. With multiple carriers on station, advanced missile defenses, and broad international backing, the coalition is confident it can counter Iran’s asymmetric tactics. However, this heavy militarization of the Strait also raises the risk of direct U.S.-Iran clashes if Iran does choose to challenge the line. The powder keg is armed on both sides – but heavily lopsided in favor of U.S. and allied capabilities if used.

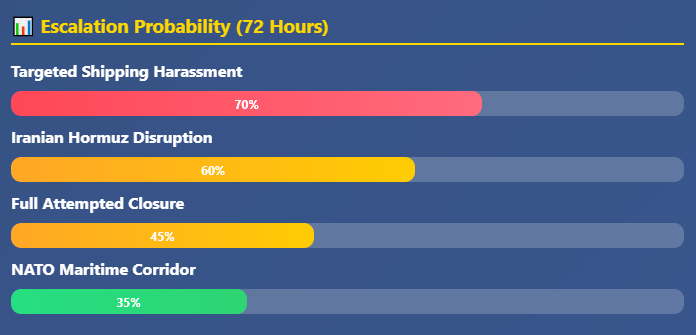

Should Iran choose to escalate in the Strait of Hormuz or more broadly, several plausible scenarios could unfold in the coming 72 hours. Below we outline the main scenarios with our assessed probability of each:

The most likely near-term scenario is targeted harassment of shipping rather than an immediate all-out closure. Iran has strong incentives to exert pressure yet stop short of an irreversible step. Small-scale attacks – such as a drone strike damaging a tanker’s hull or a short-lived boarding and seizure of a ship – would send a message while giving Iran deniability and room to de-escalate. Indeed, Iran has a history of such calibrated provocations: e.g. the April 2024 IRGC seizure of the MSC Aries container ship (which Iran justified on “violating maritime laws”) was an example of targeted action that rattled nerves without sparking war. We have already seen precursors in recent days: electronic GPS interference, and reports that some tanker operators have suspended new transits due to threat levels. These point to a harassment strategy underway.

A full closure attempt – while less probable – cannot be ruled out if Iran’s regime feels cornered (for instance, if domestic or internal pressures demand a drastic response to the Israeli onslaught). An attempted closure would likely happen suddenly, leveraging Iran’s geographic advantage: they could scuttle a large ship in the narrow channel, deploy a wave of mines overnight, and unleash dozens of missiles and swarming boats in a surprise “Day One” effort to overwhelm the strait. Initial success could see shipping halt for several days. However, we assess Iran understands that a full closure would bring overwhelming U.S. retaliation and global condemnation, possibly even loss of Chinese and Russian diplomatic cover. Thus, while we give this a 45% chance (not negligible given fog of war), Iran would likely only attempt it if further red lines are crossed (e.g. if U.S. were to strike inside Iran or attempt regime change). Even if attempted, such a closure likely could not be sustained beyond a few days due to the massive coalition response it would trigger.

The NATO/allied maritime corridor scenario is essentially the counter to any Iranian escalation. If Iran begins significant attacks, the U.S. and partners will move to implement a protected shipping lane. In effect, this could mark the start of Coalition–Iran naval skirmishes: Iran’s mines and attacking craft versus allied minesweepers, drones, and warships. We estimate ~35% chance this formal convoy system is established within 72 hours – its likelihood directly rises if Iranian harassment crosses a threshold (e.g. a tanker is sunk or heavily damaged). Notably, political groundwork is being laid: G7 leaders discussed “ensuring freedom of navigation” and countries like the UK and France have indicated willingness to participate. This scenario could de-escalate the situation by safeguarding ships, but also risks incidents (e.g. IRGC boats firing on a convoy and being sunk by NATO forces, potentially killing Revolutionary Guard personnel and further escalating the war).

Proxy escalation is already materializing in parallel. On June 15, Iranian-backed militias in Iraq launched rockets at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad (no casualties, but a clear warning). The Houthis in Yemen, strongly aligned with Iran, have dramatically increased activity in the Red Sea – they have attacked cargo ships near the Bab al-Mandeb Strait in recent months as a show of solidarity. We judge a 60% probability that Iran activates proxies in the next 72 hours to divert and stretch U.S./Allied attention. This could include drone or missile strikes on U.S. bases in Iraq/Kuwait, or Houthi launches of longer-range missiles toward Gulf shipping or even Israel. Such proxy moves broaden the theater of conflict (and indeed U.S. forces in the region are on high alert for this). While not directly closing Hormuz, these actions increase general instability and could indirectly threaten shipping (e.g. if the Red Sea becomes unsafe due to Houthi attacks on tankers, as has occurred intermittently).

Finally, involvement by Russia or China will likely be limited to the diplomatic sphere. Both have interests: China is a major oil importer from Hormuz and wants stability (and has a partnership with Iran), while Russia benefits from higher oil prices and distraction of the West. We assign ~20% probability of noticeable Russian/Chinese escalation, mainly diplomatic or symbolic naval moves. For example, Russia might send a token warship to “observe” developments or hold exercises with Iran (Moscow and Tehran have conducted joint naval drills in the Indian Ocean in the past). China could quietly dispatch a couple of PLA Navy ships from its anti-piracy flotilla to make port in Oman or Pakistan as a show of presence. Both Beijing and Moscow are also likely working at the UN Security Council to prevent a resolution explicitly condemning Iran, instead calling for ceasefire and negotiations. These actions complicate Western calculations but are unlikely to involve direct confrontation with U.S. forces. However, any mis-step (e.g. a Russian advisory presence at an Iranian naval facility that comes under U.S. fire) could create unpredictable great-power friction. For now, this remains a low-likelihood wildcard scenario.

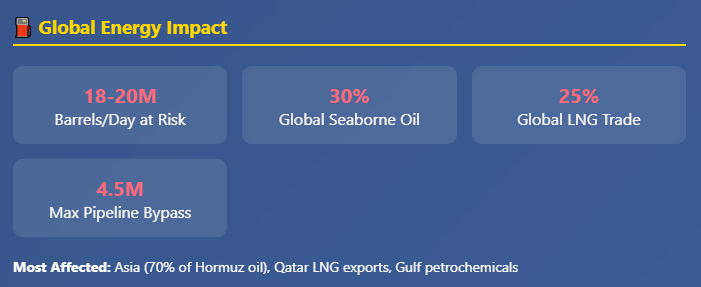

A crisis in the Strait of Hormuz has seismic implications for global energy markets. Even the prospect of disruption has already sent oil prices gyrating, and an actual closure – even temporary – would constitute a massive supply shock. As the conflict deepened in mid-June, markets reacted swiftly: on June 13 when Israel’s strikes began, Brent crude spiked +13% intraday to around $77/bbl, its highest level of the year. Though prices pulled back slightly on June 16 on rumors of a possible truce (Brent closed ~$73.23), volatility remains extremely high. The baseline assumption absent a Strait closure is that oil prices will remain elevated in the $70–80 range near-term, pricing in a geopolitical risk premium but with some hope that supplies keep flowing. However, a Hormuz disruption would likely cause an immediate surge far beyond those levels.

In sum, the global energy market is bracing for the worst while hoping for the best. As of now (June 16), oil traders have injected a hefty risk premium but are not pricing in a full shutdown (Brent ~$73, well below the feared $100+). However, market sentiment could turn on a dime with any confirmed move to block Hormuz. Expect extreme volatility: $10–20 swings in a day are possible if conflicting news (closure vs negotiations) emerges. Governments are on high alert – the IEA’s standby plans and likely OPEC+ behind-the-scenes coordination indicate that a broad effort would be made to stabilize supply in a protracted crisis. Still, no amount of strategic planning can fully nullify the impact of a Hormuz disruption, given its outsized role (carrying “nearly a third of the world’s seaborne oil” and a fifth of its LNG). The next 72 hours will be pivotal: a slide into deeper conflict could ignite an energy price inferno, whereas de-escalation or successful containment would mean the worst is averted with only a temporary price shock.

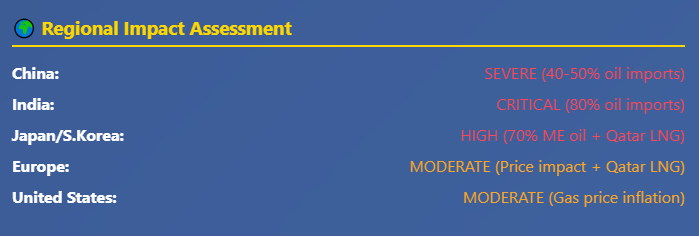

A disruption in the Strait of Hormuz would reverberate far beyond the Middle East, reshaping economic and political dynamics across the globe. Below we examine how various stakeholders and sectors would be affected and what policy responses are emerging:

American consumers are acutely vulnerable to an oil price spike, even though the U.S. imports only a modest portion of its oil from the Gulf these days. U.S. gasoline prices move with the global oil price – so a jump to $100+ oil could mean $4–5 per gallon gasoline nationally, stoking inflation again. This comes at a sensitive time: U.S. inflation had been cooling (CPI gains only 0.1% in the prior month), with gasoline prices actually falling by 2.6% in May. A Hormuz crisis threatens to “reverse the months-long trend of cooling consumer prices,” as JPMorgan analysts warned. The Biden (or rather Trump) Administration – mindful of domestic political costs – has signaled it will use the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to tamp down pump prices, and may pressure U.S. shale producers to temporarily boost output if prices soar. However, shale cannot ramp quickly in a 72-hour window, and the U.S. SPR is not as large as before. If gas prices skyrocket, expect emergency domestic measures: waivers on summer fuel blend requirements (to ease supply), perhaps even temporary suspension of the federal gas tax if the crisis endures. Politically, Trump’s tough stance on Iran plays to a “security first” narrative, but there will be pressure on him to avoid a prolonged conflict that spikes U.S. fuel costs. The U.S. aviation sector (airlines) is also exposed – jet fuel costs would surge, potentially forcing up ticket prices or causing airlines to cut routes. This in turn could affect travel and tourism recovery. In essence, a Hormuz shock could put the U.S. economy’s soft landing at risk, so the administration’s policy will likely balance assertive military action with measures to quickly stabilize oil supply (including rallying allies like Saudi Arabia to open taps via alternate routes).

Asia is the destination for ~70% of Hormuz oil and 80% of its LNG, making it the most exposed region. China, the world’s largest oil importer, receives about 40–50% of its crude from the Gulf (Saudi, Iraq, UAE, Iran). China has considerable strategic oil reserves (estimated ~1 billion barrels) and could release some to blunt short-term shortages. However, if Hormuz closes, China would face tough choices: draw down reserves, increase imports from Russia (which ironically becomes more crucial, strengthening Beijing’s hand with Moscow), and possibly ration industrial usage. Beijing will also be active diplomatically – it has friendly ties with Iran and may try to mediate or at least call for a ceasefire to reopen trade routes. The crisis might accelerate China’s efforts to diversify away from Malacca/Hormuz vulnerabilities, such as expanding pipeline routes via Russia or building more storage. India is even more vulnerable: it imports ~80% of its crude needs, much of it from Iraq, Saudi, and UAE (all via Hormuz), plus the bulk of its LNG from Qatar. An Indian expert noted that a 2-week Hormuz shutdown could be devastating, sending prices to $150 and wrecking India’s economic stability. India is likely already preparing emergency measures: sourcing extra barrels from West Africa or the U.S. (if tankers can be re-routed around Cape of Good Hope), using its small strategic reserve (India has ~39 million barrels capacity, which is just a few days’ cover), and diplomatically engaging Iran (India has a cordial relationship) to urge restraint. The Indian rupee and trade balance would suffer from sustained $120+ oil, possibly forcing government fuel subsidies or rationing to contain domestic inflation. Japan and South Korea import over 70% of their oil from the Middle East and rely heavily on Qatari LNG. They would likely tap strategic stocks (Japan holds ~90 days’ worth), and may consider restart of idle nuclear plants or other fuels if LNG supply falters. These nations will also lobby Washington and in international fora for quick resolution – Japan’s navy might even offer minesweeping help (a sensitive but conceivable move, as Japan did in a limited way after the 1991 Gulf War). Overall, Asia’s import-reliant economies could see reduced GDP growth if energy prices remain elevated; governments may intervene with consumer subsidies to cushion the blow, at the expense of fiscal health.

Europe’s direct oil import exposure to Hormuz is smaller (Europe gets more oil from the North Sea, Africa, and the Americas), but not negligible – especially after cutting off Russian oil, Europe has been buying more from the Middle East. Roughly 10–15% of Europe’s crude comes via Hormuz. Additionally, Europe receives ~20% of Qatar’s LNG, which has become more important post-Russia (some EU states have long-term contracts with Qatar). A Hormuz crisis would thus hurt Europe mainly through price – both oil and LNG spot prices would rise globally. The EU has mechanisms (like the IEA) for oil stocks; many European countries could release reserves (they hold ~120 days cover collectively). For natural gas, Europe has decent storage level now (it’s summer), but a prolonged LNG disruption would complicate refilling storage before winter and cause price spikes at the TTF gas hub. Europe’s hedging strategies might involve fast-tracking alternatives: e.g. asking Norway and North Africa to boost gas piped to Europe, switching some gas-fired power plants to burn oil if oil is somehow more available than gas (which would be unusual), and delaying the shutdown of any remaining coal or nuclear plants to save gas. On oil, Europe can increase imports from places like Nigeria, Angola, or even ease sanctions on some producers (one outside possibility: a quick deal with Venezuela or Iran to allow more of their oil – though Iran is the issue here so that’s moot unless a broader peace deal). The EU also might coordinate a consumption reduction campaign – e.g. lower speed limits or work-from-home directives – if fuel shortages loom. Politically, high fuel costs could fan inflation and hurt European economies that are already fragile, but the EU is relatively united on supporting Israel/U.S. stance so far. If the crisis drags, we could see splits – countries like Germany or France pushing harder for a diplomatic solution to get oil flowing, even if it means pressuring Israel to pause, whereas Eastern European states (less affected by Middle East oil) might be more hawkish.

OPEC, BRICS, and Russia: The OPEC+ producers find themselves in a delicate spot. On one hand, they benefit from higher prices (Russia especially, as it has been selling oil at a discount due to sanctions – a rising Brent lifts even the discounted Urals price). On the other hand, a huge spike that causes demand destruction or global recession isn’t in their long-term interest. Saudi Arabia and the UAE – key OPEC members and U.S. partners – would likely try to thread the needle: they might publicly blame Iran for destabilization, but also quietly enjoy short-term price windfalls. Saudi’s Energy Minister could convene an extraordinary OPEC meeting to discuss output policy – perhaps offering a token increase in production to show “responsibility”. However, if the oil physically can’t ship out, that’s moot. Saudi could do a small gesture like offering extra barrels via the Red Sea route to Europe to calm that market. Russia, a member of OPEC+, stands to profit from chaos – its Urals crude could become more attractive to big importers like China and India if Middle East supplies falter. Indeed, news reports note Russian oil prices jumped ~15% after the conflict outbreak. So Russia has incentive for the crisis to simmer. Diplomatically, Russia will back Iran in UN forums, blocking any resolution that might legitimize Western military action. We might also see Russia step up covert supplies to Iran (weapons, intelligence) as a tit-for-tat for Western support to Ukraine. China (part of BRICS) is in a tricky spot: it values Iran as a partner and is part of a new BRICS development, but it desperately needs stability for its energy imports. China might use BRICS or SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Org) platforms to call for a new security architecture in the Gulf that reduces U.S. presence – capitalizing on the situation to push its narrative – but in immediate terms, China likely is urging Iran via back-channels not to escalate too far. BRICS collectively (Brazil, India, China, Russia, South Africa) might issue a statement decrying violence and U.S. interference, but there will be internal splits (India won’t support Iran’s actions that send its oil bill soaring). Global Alignment Shifts: If the crisis intensifies, it could accelerate moves by countries like China and India to create alternative payment mechanisms or supply routes (for example, using Chinese yuan to pay for Gulf oil if U.S. sanctions tighten, or investing in pipelines like an Oman-India undersea pipeline which has been floated conceptually). It could also give momentum to dialogues like a “Hormuz Peace Initiative” involving regional players – something Iran has pitched before – but such ideas usually gain traction only after conflict peaks.

Companies in various sectors should prepare now. Energy companies and traders are already rerouting tankers (some ships are taking the long way around the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Gulf) – firms like Shell and Exxon have contingency routing plans. They are also likely using financial hedges; refiners will want to hedge crack spreads, airlines hedge jet fuel, etc. Shipping companies are instructing vessels to adopt “gray man” tactics – such as turning off AIS in dangerous zones (though that has its risks) or hugging the Omani coast (where Iranian fast boats are less likely to operate freely). Marine insurers have hiked war-risk premiums; some shipowners may demand governments provide indemnity (as in the 1987 U.S. re-flagging of Kuwaiti tankers). Corporate risk managers in sectors from chemicals to automotive (which rely on oil/naphtha feedstocks) should brace for supply chain and price disruptions. Logistics managers might front-load shipments – e.g. import extra crude or LNG now before any closure – effectively stockpiling onshore inventories. Those with storage (tank farms, LNG tanks) are filling them as a buffer.

Recommendations for Private Sector:

A protracted Hormuz crisis could realign some relationships. The U.S.-Gulf Arab partnership would tighten as these states rely on U.S. protection – but if the U.S. is seen as not doing enough, Gulf states might consider more independent defense (or conversely, if the U.S. takes very hard action, they may worry about being targetted by Iran and urge restraint). Iran’s regional standing could suffer if it is blamed for economic pain – already some of Iran’s neighbors (e.g. UAE, Saudi) are quietly furious at Tehran’s aggression. However, within Iran, the regime might rally nationalist sentiment around standing up to “American-Zionist plots” by using Hormuz as leverage. Domestically in the U.S., a conflict that spikes gas prices could become a campaign issue (Trump would be under pressure to show strength but also to end the conflict quickly to stabilize prices). International law and norms: Freedom of navigation in Hormuz is protected by international law; if Iran closes it, there could be moves to form an international naval coalition under perhaps a UN mandate (similar to Korean War navies in 1950 or tanker escorts in 1987 under UN SCR resolutions). If diplomacy wins out, we might even see talk of a new “Hormuz Security Guarantee” – perhaps an agreement where Iran gets some sanctions relief or security assurances in exchange for pledging not to impede shipping (this is speculative, but stakeholders may seek a formal accord after coming to the brink).

In conclusion, the Hormuz flashpoint is a stark reminder of global interdependence. Every extra day of closure risks cascading economic fallout – surging fuel costs, slowed growth, and jittery financial markets. Already, stock markets worldwide have wobbled (the S&P 500 fell ~1.7% on the war news, and airlines/shipping stocks are down). The crisis also provides adversaries like Russia a potential windfall and leverage. Mitigating these risks will require both deft military containment and savvy economic management.

Ultimately, managing “Flashpoint Hormuz” requires both hard security measures to deter immediate threats and soft economic tools to cushion the blow. The next 72 hours will test the world’s ability to prevent a regional war from triggering a global energy and economic crisis. The intelligence thus far suggests Iran is weighing its options carefully – its jamming and isolated naval posturing signal intent, but not irreversible commitment to the worst-case path. The presence of overwhelming U.S.-led forces and intense diplomatic efforts (including by Russia/China behind the scenes) may yet avert a catastrophe. Nonetheless, all actors are now on high alert – with warships, markets, and negotiations moving in unison in the shadow of Hormuz.

All forecasts in this brief are based on information available as of June 16, 2025 at 20:30 EDT (June 17 00:30 UTC) and are subject to revision with new intelligence.