Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

In July 2025, a long-simmering border dispute between Cambodia and Thailand erupted into the most intense clashes in over a decade, threatening regional stability. What began as a brief firefight in late May escalated by late July into heavy artillery duels and even air strikes along multiple points of the frontier. At least two Thai civilians have been killed by Cambodian rocket fire and several Thai soldiers wounded【6†L41-L49**, while Cambodia accuses Thailand of bombing its territory with F-16 fighter jets【10†L207-L214】. Tens of thousands of civilians have been evacuated from Thai border villages amid intermittent shelling, and both countries have largely shut their border crossings, severing trade and travel. Diplomatic ties are at their nadir: ambassadors have been recalled and expelled in tit-for-tat reprisals, and official communications reduced to hostile exchanges in international forums.

This intelligence brief provides a forward-looking, multi-domain assessment of the crisis. It integrates open-source intelligence (OSINT) on military deployments, cyber activities, and economic disruptions, conflict pattern analysis from past Thai-Cambodian skirmishes, and regional diplomatic context to forecast possible trajectories. Key findings include:

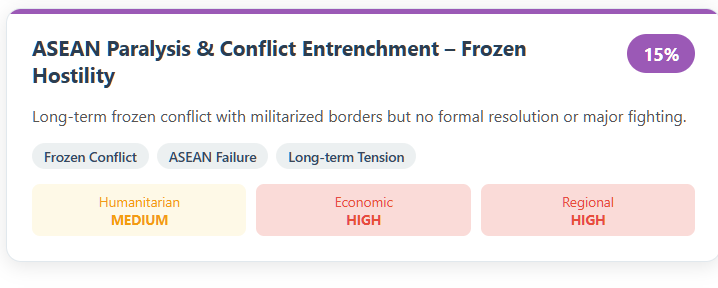

Looking ahead 30–90 days, we outline five plausible scenarios with associated probabilities and outcomes. These range from a legally-brokered cooling-off to a worst-case of protracted conflict and regional fracture. Each scenario in the following matrix is assessed with its likelihood and potential consequences:

These scenarios and probabilities will be revisited in later sections with more detail. In all cases, the coming 2–3 months are pivotal: they will determine whether this flashpoint is extinguished through diplomacy or explodes into a wider conflagration.

Key events from February to July 2025 leading to military escalation

Early 2025 – Rising Tensions: The seeds of the current crisis were visible at the start of 2025. On February 13, 2025, a cultural fracas occurred at the Ta Muen Thom temple (on the border between Thailand’s Surin province and Cambodia’s Oddar Meanchey). Thai soldiers prevented a group of Cambodian visitors from singing Cambodia’s national anthem at the disputed cliff-top temple, angering Cambodian nationalists. Though small, this incident inflamed public sentiment and hinted at the contentious status of ancient temples along the border – a long-standing trigger for bilateral tensions. In the cyber domain, by March 2025 Cambodian hacktivists (AnonSecKh) had already mobilized; the group began probing Thai government sites in late March, signaling that nationalist fervor was spilling into cyberspace even before shots were fired.

28 May 2025 – Border Clash at Chong Bok: The conflict’s opening salvo came on May 28, when Thai and Cambodian troops exchanged gunfire in a remote border area near the “Emerald Triangle” trijunction (Chong Bok, where Thailand’s Ubon Ratchathani, Cambodia’s Preah Vihear, and Laos meet). The skirmish – lasting about 10 minutes – killed one Cambodian soldier (2nd Lt. Suon Roun) and wounded several on both sides. Each country immediately blamed the other for firing first: Cambodia’s defense ministry said Thai soldiers intruded and opened fire on a Cambodian post, whereas the Thai Army claimed its patrol encountered Cambodian troops dug in on Thai soil and had attempted to persuade them to withdraw before Cambodians opened fire. This deadly clash abruptly ended a period of relative calm and plunged relations to their lowest point since 2011. Both sides rushed reinforcements to the area in the ensuing days. Notably, Cambodia’s PM Hun Manet quickly announced plans to take the matter to the ICJ the very next day (May 29), signaling a legalistic approach. Thailand’s defense minister, however, played down the clash as resolved and insisted neither side wanted escalation. On 29 May, top Thai and Cambodian generals met face-to-face and agreed to “preserve stability” and improve communication to prevent further incidents. For a brief moment, it appeared cooler heads might prevail.

Late May – Early June 2025 – Diplomatic Overtures and Militarization: Despite the generals’ talks, the situation simmered. On June 5, bilateral negotiations at a Joint Boundary Commission (JBC) meeting failed to produce a breakthrough. Thai officials reported that Cambodia rejected Thai proposals, and on June 7 Thailand’s army announced it would bolster its border deployments. The Thai military also accused Cambodian civilians of increased incursions and “provocations” in border jungles, interpreting Cambodian troop movements and engineering works (like clearing trees and building roads) as “a clear intent to use force”. Thailand’s National Security Council that week gave the Army greater authority over border security, empowering regional commanders to close checkpoints at their discretion. In parallel, Cambodia moved on the economic and propaganda fronts: on June 17, Phnom Penh announced a ban on Thai fruit and vegetable imports and Thai TV dramas – ostensibly to reduce economic reliance on Thailand amid the dispute. This was a striking echo of past tit-for-tat cultural boycotts (such as during the 2003 anti-Thai riots in Cambodia). Both nations also enacted travel advisories: Cambodia warned its citizens against visiting Thailand, while Thailand cautioned Thais in Cambodia to avoid any “protest areas”. The conflict was broadening beyond the battlefield, touching trade and people-to-people ties.

Mid-June 2025 – The Leaked Call and Political Fallout: A turning point came in mid-June, not on the border but in the diplomatic shadows. On 15 June, Thai PM Paetongtarn Shinawatra – increasingly desperate to calm tensions – arranged a secret phone call with Cambodia’s ex-strongman Hun Sen. Lacking trust in official channels, Paetongtarn even used an intermediary interpreter (a Cambodian official) to speak frankly with Hun Sen. In the call, she beseeched Hun Sen for help in defusing the border crisis, admitting she was under domestic pressure and urging him to discount the hardline views of Thai military officers at the frontier. Crucially, Hun Sen recorded the conversation – and on 18 June he publicly released the audio on social media without warning. The contents caused a political firestorm in Bangkok. Paetongtarn’s unguarded, almost supplicating tone with Hun Sen, and her reference to the Thai armed forces as a “rival faction” opposing her government, were seized upon as proof of weakness and disloyalty. Within hours, Paetongtarn’s coalition began to unravel: the Bhumjaithai Party (a key partner) quit the government on the night of June 18, robbing her of a parliamentary majority. Protests erupted in Bangkok calling for her resignation. and the stock market plunged over 4% in three days amid the political uncertainty. Although Paetongtarn apologized publicly and insisted she only sought a peaceful solution, the damage was done. On July 1, Thailand’s Constitutional Court suspended Paetongtarn from duty pending an investigation into whether the call and her conduct violated ethics and national security rules. Deputy PM Phumtham Wechayachai became acting premier, inheriting the border crisis under far more precarious political conditions. The leaked-call saga not only weakened Thailand’s civilian leadership but emboldened the Thai military’s influence – a dynamic that would soon be reflected in its escalatory responses on the ground.

Late June 2025 – Cracks in Peace Efforts, Economic Tit-for-Tat: In the wake of the call leak, diplomatic efforts seesawed. On one hand, China’s government stepped in diplomatically at the ASEAN foreign ministers meeting in Kuala Lumpur on July 11: Chinese FM Wang Yi urged Thailand and Cambodia to resolve the dispute through dialogue and offered to mediate “objectively and fairly.” (In those meetings it emerged that Cambodia had formally reached out to the ICJ in June to adjudicate the border issues, underscoring Phnom Penh’s legal approach). On the other hand, Cambodia escalated economic pressure: on June 22, Prime Minister Hun Manet ordered a halt to all fuel and gas imports from Thailand. This move took effect at midnight, immediately cutting off roughly 2.3 billion liters of Thai petroleum exports per year that Cambodia relies on (about 29% of its fuel supply). Cambodia declared it would source fuel from Vietnam, Singapore and others to compensate. The fuel ban not only hit Thai energy firms (e.g. PTT) but also signaled Cambodia’s willingness to endure economic pain for the sake of national pride. Simultaneously, Phnom Penh cut certain internet and telecommunication links with Thailand around this time – possibly to prevent Thai media influence or even to guard against Thai cyber intrusions. The last week of June saw these tit-for-tat measures pile up, even as sporadic border incidents (patrol stand-offs, warning shots) continued to be reported by local media.

Mid-July 2025 – Landmine Incidents and Diplomatic Downgrades: The conflict took another deadly turn in mid-July. On July 16, three Thai soldiers on patrol in a contested border sector were injured by an antipersonnel landmine blast. Thailand alleged this was a newly planted mine laid by Cambodian forces to hinder Thai patrols. Cambodia’s officials vehemently denied it, insisting no new mines were deployed and suggesting the Thais wandered into an old minefield from decades past. Tensions spiked further on July 22 when another Thai soldier triggered a landmine near the border, losing his right leg in the explosion. This second incident in a week proved to be a diplomatic breaking point. That evening, Thailand’s ruling Pheu Thai Party (still in government under acting PM Phumtham) announced it was recalling Thailand’s ambassador from Phnom Penh and expelling Cambodia’s ambassador in Bangkok. Essentially, diplomatic relations were downgraded to the lowest level, with only chargé d’affaires remaining. Cambodia retaliated in kind within hours – its foreign ministry withdrew all Cambodian diplomats from Thailand and ordered Thai diplomats out, reducing ties to minimal “second-secretary” contacts. This mutual expulsion harked back to the worst days of past crises (not seen since a 2003 rupture). It also closed off direct dialogue between governments just as the military situation was about to explode. Notably, on July 23, Thailand’s Second Army Region commander ordered all remaining border checkpoints closed, citing the landmine attacks and security concerns. By the morning of July 24, the entire land border was effectively sealed – no trade convoys, no tourists, no local border traffic.

24 July 2025 – Major Border Escalation (Ta Muen Thom and Preah Vihear): Full-scale fighting erupted in the early hours of July 24 along multiple border flashpoints, marking the worst violence of the crisis. Around dawn, Cambodian troops advanced toward the disputed Ta Muen Thom temple area (called Prasat Ta Moan by Cambodia) and, according to Thai reports, opened fire on a Thai outpost after Thai soldiers spotted a Cambodian drone overhead and tried to warn them off. Cambodia claims the opposite – that Thai troops crossed into their territory near the temple and Cambodian forces responded in self-defense. Either way, intense firefights broke out at Ta Muen Thom (Surin province) just after 9:00 am, with Cambodian units firing RPGs, mortars, and artillery across the border. Thailand’s military, which had pre-planned for such incidents under an “Operation Chakrabongse” contingency, retaliated with its own artillery barrages. Clashes then spread to at least five other locations: notably the vicinity of Preah Vihear Temple (called Khao Phra Wihan on the Thai side in Sisaket province) and border passes like Chong An Ma, Chong Bok, Ta Kwai, and Chong Chom. Cambodian forces deployed BM-21 “Grad” 122mm rocket launchers in the fray, dramatically escalating the firepower used. By late morning, Thai authorities reported two villagers in Surin killed by Cambodian rocket strikes on Ban Jorok village, with others including a young boy wounded. Thai district officials urgently evacuated civilians; ultimately about 40,000 Thai residents from 80+ villages were moved to shelters (often schools or temples reinforced with sandbags) away from the range of Cambodian guns. Videos from Thai media showed residents huddled in bunkers and makeshift bomb shelters while artillery boomed in the distance.

At midday on July 24, the stakes rose further: Thailand’s Air Force struck back from the skies. The Royal Thai Army confirmed it had deployed six F-16 fighter jets to the border theater, and one of them conducted a strike, dropping bombs on what Thailand described as a Cambodian “military target” on Cambodian soil. Cambodia’s defense ministry acknowledged the airstrike, saying Thai jets dropped two bombs on a rural road in Oddar Meanchey province. This marked the first use of airpower in the conflict – a significant threshold crossed. Both sides by this point openly accused the other of starting the battle, even as firefights continued through the day. Cambodian PM Hun Manet announced that Thai forces had attacked Cambodian positions at Prasat Ta Moan Thom and nearby Prasat Ta Krabey (another temple ruin) and that Cambodia “had no choice but to respond with armed force against armed aggression.” Concurrently, Thai officials cited the drone sighting and Cambodian forward movement as evidence that Cambodia staged a provocation to justify an attack. By late afternoon July 24, reports indicate the exchanges of fire had calmed, but the border remained extremely volatile. Thailand announced it was “closing all border points” indefinitely (which had largely already occurred). Both militaries were placed on their highest alert; Thailand’s Second Army Region vowed to “confidently defend” against further incursions, and Cambodia reportedly began shifting additional units toward the frontier overnight.

Late July 2025 – Humanitarian and OSINT Developments: In the days following July 24, the humanitarian situation along the border is precarious. Over 100 Thai schools near the frontier have been ordered closed for safety. Relief efforts are focusing on the displaced Thai villagers, providing food and medical care in shelters. There is scant information on the Cambodian side’s civilian situation – Cambodian media (tightly controlled by the state) have not reported evacuations, but ex-PM Hun Sen mentioned Thai shelling in two Cambodian provinces (Preah Vihear and Oddar Meanchey) which likely implies some Cambodian villagers also fled or took shelter. Casualty figures beyond the initial Thai civilian deaths remain unverified; Thai sources claim “dozens” of Cambodian soldiers may have been killed or injured by the F-16 strike and counter-fire, but no official confirmation. OSINT analysts are scrutinizing satellite images from Maxar and Sentinel-2: preliminary imagery from July 25 shows new crater impacts near Ta Moan and smoke damage along border ridges (indicative of artillery concentrations). Cyber front: Following the kinetic escalation, pro-Cambodian cyberattacks surged again – on July 24–25, hacker group AnonSecKh bragged on Telegram about defacing Thai provincial government websites and dumping data, as a “digital retaliation” for Thai airstrikes. Thai cybersecurity agencies are in overdrive to contain these breaches. Both countries are also actively shaping the information war: Thailand’s Foreign Ministry has submitted a letter to the UN Security Council detailing Cambodia’s “aggression” (likely for the record and potential UNSC discussion), while Cambodia’s diplomats have been giving international media their narrative of Thai provocation and calling for outside mediation.

This timeline illustrates how quickly a localized shootout spiraled into a multi-domain conflict. It also highlights key incident triggers (e.g. the landmine blasts, the phone leak) and the interplay between on-the-ground events and diplomatic/cyber responses. Each phase has built upon the previous, leading to the dangerous impasse we see as of late July 2025.

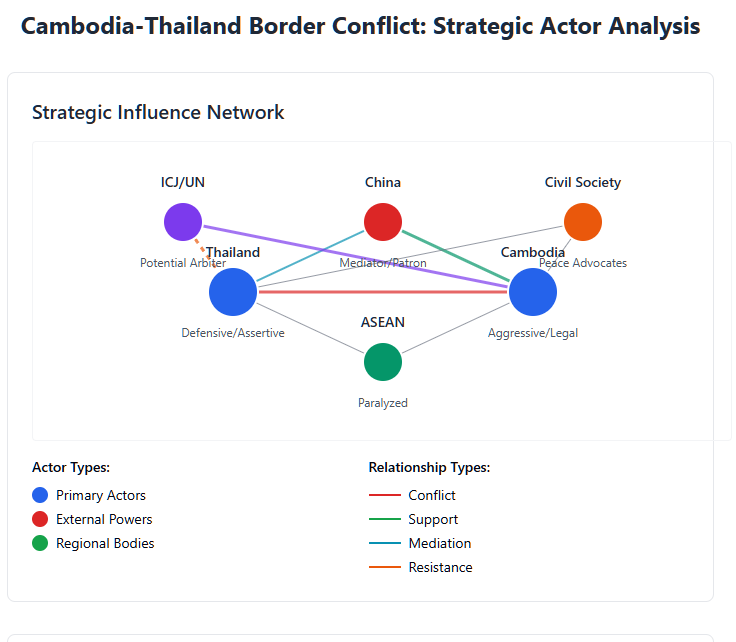

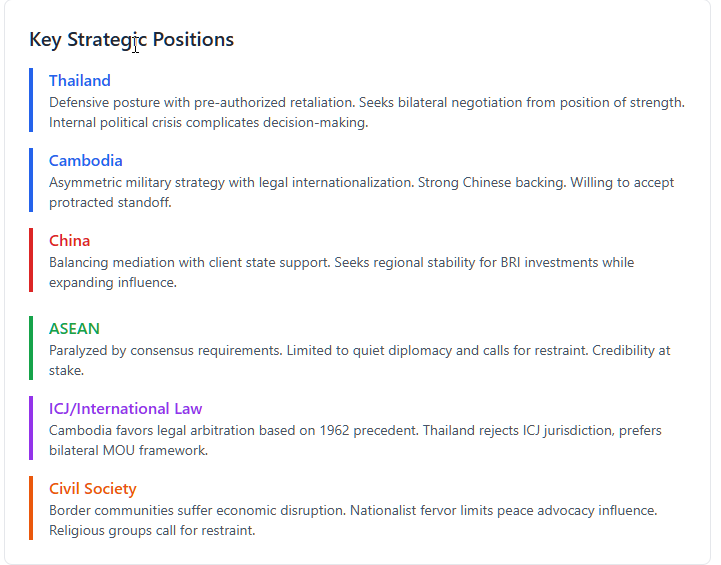

Understanding the motivations and constraints of each key actor is crucial to forecasting the crisis. Below is an analysis of the strategic positions of the main stakeholders – Thailand, Cambodia, China, ASEAN, international legal institutions, and civil society – and how each influences the conflict’s trajectory.

Military Posture: Thailand’s Armed Forces, particularly the 2nd Army Region, are on high alert and have taken a forward-leaning stance. The Thai military has invoked contingency plans like the “Chakrabongse Bhuvanath Plan” to respond to border incidents, effectively giving field commanders pre-authorized rules of engagement for robust retaliation. Since early June, Thailand reinforced troops along the border – the Defense Minister acknowledged new deployments after Cambodia rebuffed initial peace proposals. Thai units, including rangers and paramilitary Thahan Phran, are entrenched near flashpoints (Surin, Sisaket, Ubon Ratchathani provinces) and have orders to “defend every inch” of territory. The Thai Air Force’s willingness to deploy F-16s demonstrates the military’s resolve to dominate escalation if needed. Notably, the Thai military has also been active in information operations: releasing aerial reconnaissance photos purportedly showing Cambodian buildups (e.g. newly dug trenches, road construction in contested zones) to justify its security measures. It has also publicly accused Cambodia of illegal tactics like laying new landmines and targeting civilians, to bolster Thailand’s moral high ground.

Political Leadership and Intent: The Thai government’s stance is complicated by internal turmoil. With PM Paetongtarn suspended, Acting PM Phumtham Wechayachai (who is also Defense Minister) has struck a cautious tone: “We have to be careful… We will follow international law,” he told reporters, emphasizing measured action. This indicates Thailand does not seek a full-blown war and is mindful of global opinion. However, the embattled civilian leadership is under intense domestic pressure to show strength. Thai opposition parties and nationalist voices criticize any perceived leniency; even before her suspension Paetongtarn was lambasted for being “too soft” on Cambodia. The Royal Thai Army, while formally under civilian control, now enjoys greater autonomy in this crisis – and its interests align with a firm response. Historically, the Thai military and monarchy have an arch-nationalist view on territorial issues, especially regarding the Cambodian border (e.g. the Preah Vihear temple saga was a rallying cause for Thai ultra-royalists in 2011). As such, Thailand’s strategic intent is to assert its territorial claims and deter further Cambodian advances, without appearing as the aggressor internationally. The government likely aims to push Cambodia back to the status quo ante (e.g. no Cambodian military presence in disputed zones) and then negotiate from a position of strength. Importantly, Thailand has rejected international arbitration (fearing loss of territory in court) and insists on bilateral negotiation under existing frameworks. So while Bangkok publicly says it remains open to talks, it has set a precondition: Cambodian forces must stand down first. This stance, coupled with the internal political fragility, means Thailand is likely to continue a tough military posture in the immediate term, hoping to force Cambodia into compliance or at least contain the situation until Bangkok’s political crisis is resolved.

Economic and Security Interests: Thailand’s immediate interests are to re-open the border and resume normal trade – but only once security is assured. The closure of crossings hits Thai border provinces economically (Thailand enjoyed a ~$3 billion trade surplus with Cambodia). However, Thai officials have justified the closures and even power/fuel export cuts as security measures to crack down on scams and illegal activity emanating from Cambodia. This dual rationale indicates Thailand is leveraging economic tools as pressure. Strategically, Thailand also seeks to avoid pushing Cambodia so far into China’s embrace that it results in, say, a permanent Chinese military presence next door. Thai policymakers thus face a balancing act: punish Cambodia enough to curb its actions, but not so much that Phnom Penh “locks in” a Chinese security alliance. In the longer run, Thailand’s alignment is subtly shifting – with relations with the U.S. improving (after cooler ties post-2014 coup) and joint military exercises (like Cobra Gold) emphasizing readiness. The border crisis may drive Thailand to quietly consult with U.S. advisors or request intel support to monitor Cambodian troop movements, invoking its treaty ally status if the conflict worsens. Thailand also values its reputation as a regional leader; enduring a drawn-out fight with a smaller neighbor harms that image. So, a strategic goal for Thailand is to resolve this dispute on its terms relatively quickly, to refocus on domestic governance and ASEAN cooperation. If the conflict drags, one cannot rule out more drastic moves from Bangkok’s establishment – including, conceivably, a military-directed government “for unity” (if hawks argue civilians are incapable of handling national security). In sum, Thailand is determined, under strained leadership, to defend its border and national pride, seeking a controlled de-escalation that doesn’t involve territorial concessions or foreign adjudication.

Military Posture: Cambodia’s Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF), particularly the 4th Military Region, have taken an unusually aggressive forward stance for what is a smaller military power vis-à-vis Thailand. Cambodian units (army infantry with reinforcement from elite Border Force units) established forward posts in disputed areas earlier this year – for instance, digging trenches near Chong Bok that Thailand objected to. Since May, Cambodia has moved artillery batteries (including truck-mounted multiple rocket launchers) into border positions within Oddar Meanchey and Preah Vihear provinces. The use of BM-21 Grad rockets and 122mm artillery in July’s clashes shows Cambodia’s willingness to employ heavy firepower, likely hoping to deter Thailand by threatening painful costs. Cambodia’s armed forces are battle-hardened from internal conflicts decades ago but have limited experience in conventional interstate war; nevertheless, longtime ruler Hun Sen (though officially retired) was a former battlefield commander and likely advised his son’s government to project strength. Indeed, Hun Sen ominously warned “We won’t just resist, we will strike back” if Thailand keeps up aggression, invoking memories of the 2011 Preah Vihear conflict. Strategically, Cambodia’s military knows it cannot win a full war with Thailand – its air force and navy are negligible and its army, though numerous, lacks the advanced hardware of the Thais. Thus, Cambodia’s military strategy is asymmetric: hold defensible positions around disputed temples (like Preah Vihear, Ta Moan, Ta Krabey) and use long-range fires (rockets, artillery) to make any Thai incursion costly. They have also leveraged drones for reconnaissance (and possibly for guiding rocket fire), indicating a modernizing force within its limits. Cambodia likely pre-positioned supplies and munitions at border bases (e.g. in Anlong Veng and Tbeng Meanchey) anticipating a protracted standoff. Notably, there are signs Cambodia may have mobilized reservists or militia; after the July 24 clashes, unconfirmed OSINT reports showed convoys of trucks carrying troops east from Phnom Penh – possibly the Royal Cambodian Guard or gendarmerie units being sent to bolster border defenses.

Political Leadership and Intent: Prime Minister Hun Manet, though in power for less than a year, is clearly taking guidance from his father Hun Sen’s playbook of strongman nationalism. The Cambodian government’s intent is to vigorously defend what it views as its sovereign territory and not be seen as bowing to Thai pressure. Cambodian leaders frame the conflict as continuation of historic injustices – a narrative of defending Cambodian soil (often referring to colonial maps and ICJ decisions). From the outset, Cambodia pursued a dual strategy: military firmness on the ground, and legal/diplomatic outreach internationally. Hun Manet and Foreign Minister Prak Sokhonn have reached out to the UN and ICJ, calculating that global opinion might favor tiny Cambodia against a larger Thailand if Cambodia appears the victim seeking rule-of-law solutions. Domestically, the crisis has been a rally-around-the-flag moment. Hun Sen, though formally “retired,” maintains a huge influence (he regularly posts on Facebook about the conflict) and his long-cultivated nationalism sets the tone. Cambodian state media and officials emphasize that Cambodia will not yield an inch of land and will meet Thai “aggression” with force. The passage of a conscription law activation is telling – it indicates that Phnom Penh is readying for a scenario where a long confrontation or even wider conflict might emerge. By reviving the draft (dormant since 2006), Hun Manet signals both resolve and an opportunity to instill patriotic duty among the youth, bolstering his legitimacy as a wartime leader. Politically, the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) faces little opposition domestically (it won every seat in the 2023 election), so there’s no internal dissent to moderating the stance; if anything, any Cambodians critical of the war risk being labeled unpatriotic. Therefore, Cambodia’s strategic intent is likely to internationalize the conflict while solidifying internal unity. They want the ICJ or UN involved, believing legal precedent (like the Preah Vihear case) favors them, and they want to galvanize Cambodians with a narrative of resisting Thai bullying. The ultimate goal for Cambodia would be a settlement that confirms its sovereignty over contested areas (especially around the Preah Vihear and Ta Moan Thom temples) and ideally forces Thailand into some concessions or face-saving measures for Cambodia. If that’s not immediately attainable, Phnom Penh seems prepared for a drawn-out standoff, counting on international sympathy and Chinese support.

Alliances and External Support: Cambodia has long tilted towards China for strategic support, and this crisis underscores that reliance. Chinese military aid to Cambodia (training, arms sales) has ramped up in recent years, and OSINT suggests new Chinese-supplied equipment – possibly drones or artillery – has entered Cambodian service during the tensions. China’s offer to mediate is congenial to Phnom Penh; Beijing is a friendly broker compared to ASEAN or Western nations. Cambodia will likely accept Chinese intelligence or logistical help quietly (for instance, Chinese surveillance assets might share info on Thai troop movements). Vietnam, historically Cambodia’s security partner, is a quieter factor – while Vietnam has its own wary eye on Thai influence, it likely stays neutral publicly, but may coordinate with Cambodia behind closed doors given their alliance (Vietnamese and Cambodian armies have interacted closely since the 1980s). Cambodia might try to leverage Vietnam as a supplier of fuel and goods during the Thai embargo (indeed, Cambodian state media noted alternative imports from Vietnam to replace Thai fuel). ASEAN as an institution is less influential for Cambodia; having a dispute with a fellow ASEAN member, Cambodia has shown in the past (e.g. ASEAN meetings in 2012 when Cambodia was chair) that it will prioritize its national interest over ASEAN consensus. In this conflict, Cambodia likely views ASEAN’s silence as tacit permission to seek help elsewhere (China). One other interesting alliance aspect: Hun Sen’s personal rapport with the Shinawatra family (Thaksin was once an economic adviser to Cambodia) initially suggested Cambodia might be conciliatory to Paetongtarn’s government. However, the publicization of Paetongtarn’s call, likely authorized by Hun Sen, indicates Cambodia did not ultimately pull punches to save her political fate – an alliance of political dynasties gave way to realpolitik and the benefit of embarrassing Thailand. Going forward, Cambodia will expect solid backing from China and perhaps Russia (diplomatically at UN). Its strategy will be to hold out militarily until external pressure forces Thailand to negotiate on terms favorable to Cambodia. In summary, Cambodia is punching above its weight – using law, diplomacy, and its patron network – to compensate for its military inferiority, with the unwavering aim of defending its perceived territorial rights.

Stake and Stance: China’s interest in the Cambodia–Thailand conflict is twofold: regional stability for its investments, and geopolitical influence. China has poured massive investments into Cambodia under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – including the new deep-water port at Sihanoukville, special economic zones, hydropower dams, and a controversial (possible) naval facility at Ream. A prolonged conflict threatens these interests indirectly by destabilizing Cambodia’s economy and security. It could also endanger Chinese nationals in Cambodia (who work in BRI projects or the widespread Chinese-run casinos and, pertinently, the illicit online scam operations based in border towns like Poipet). Indeed, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, in his July 11 remarks, specifically emphasized the need to protect Chinese (and Cambodian) citizens and crack down on cross-border crimes like online gambling and fraud that thrive in conflict zones. This underscores China’s desire for stability and law enforcement cooperation, as those criminal enterprises have victimized people in China as well.

At the same time, China sees an opportunity to expand its influence by mediating the dispute. Beijing has taken an “objective and fair” public posture, offering constructive help but officially staying neutral. Unofficially, China’s sympathies lean towards Cambodia – a close client state – but China also values its growing ties with Thailand (Thailand is part of China’s extended economic corridor plans and a longstanding trade partner). Thus, China must balance being protector of Cambodia with not alienating Thailand. So far, China has been careful: it reiterated neutrality when meeting both Thai and Cambodian foreign ministers, and it has not openly blamed either side.

Mediation Role: China’s proposal to mediate is a strategic move to assert itself as the indispensable power in Southeast Asia. If ASEAN cannot solve the fight and the U.S. remains on the sidelines, China stepping in could yield diplomatic prestige. Beijing likely envisions brokering a ceasefire or framework where both sides halt military activities and possibly implement joint patrols or observers (perhaps with Chinese “technical advisors” involved, thus embedding Chinese influence on the ground). This would align with China’s push for an Asian security architecture not reliant on Western intervention. However, China will only invest its political capital if it believes both parties might acquiesce. Early signals: Thailand hasn’t outright rejected Chinese mediation (and indeed sent its foreign minister to talk with Wang Yi), and Cambodia would welcome it, given Hun Sen’s administration is very close to Beijing. Therefore, we assess China’s mediation offer as genuine, albeit with self-interest: a success would bolster China’s argument that Asian problems need Asian (read: Chinese) solutions. Conversely, if fighting escalates unpredictably, China might hold off deeper involvement to avoid being entangled in a shooting war.

Strategic Calculations: In the scenario of escalation, if Thailand were to seriously threaten Cambodian forces or regime stability, China might quietly increase military aid to Cambodia – such as fast-tracking delivery of air defense systems or providing satellite intelligence. But overt intervention (like Chinese “peacekeepers” or force) is highly unlikely unless the conflict bizarrely drew in other great powers. China will more likely leverage its economic sway: for instance, it can offer Thailand incentives (investments or trade benefits) to agree to a ceasefire, and simultaneously assure Cambodia of security guarantees. It’s also possible China coordinates with Russia or India to shape UN Security Council or international responses (China and Russia could jointly block any UNSC resolution that penalizes Cambodia, for example, thereby implicitly backing Cambodia’s position). Another angle: If ASEAN fractures, China might use the situation to promote its own multilateral forum or underscore the ineffectiveness of U.S.-aligned systems, hence why Southeast Asia should look more to Beijing. In summary, China is playing a long game – it wants to prevent a war that destabilizes its backyard, resolve the conflict in a way that both sides feel indebted to Beijing, and prevent external (Western) meddling. The crisis thus far is giving China a stage to show “great power responsibility” in contrast to a silent Washington. However, Beijing must tread carefully: open favoritism toward Cambodia could push Thailand (historically a U.S. ally) back closer to Washington, undermining China’s efforts to woo Bangkok. So far, China’s strategy has been to voice support for dialogue and ASEAN centrality (even as ASEAN flounders) while being ready to step in behind the scenes. This carefully calibrated approach is likely to continue, as China’s best outcome is a swift end to fighting without damage to its relationships or projects – a delicate but not impossible balancing act.

ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations): ASEAN’s founding principle is peaceful settlement of disputes, yet this crisis finds the organization largely impotent. The ASEAN Charter and the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation commit members to “exercise restraint” and not use force against each other. However, ASEAN operates by consensus and non-interference, which has meant that unless both Thailand and Cambodia seek ASEAN mediation, the bloc cannot do much. So far, no joint ASEAN statement has been issued (in contrast to 2011, when Indonesia, as Chair, convened foreign ministers to address the Preah Vihear clashes). It appears Malaysia’s PM Anwar Ibrahim (2025 Chair) has attempted personal mediation – reportedly he has spoken to both Hun Manet and Paetongtarn/Phumtham to urge calm. Malaysian and Indonesian diplomats have floated deploying ASEAN observers to the border, but Thailand in particular is lukewarm on that idea, perceiving it as potentially infringing on sovereignty (this was also an issue in 2011). ASEAN’s default mode is “quiet diplomacy”, which in practice looks like inaction publicly.

However, the longer the conflict continues, the greater the pressure on ASEAN to act. Other member states fear the precedent of an intra-ASEAN war. The Philippines and Singapore have informally called for adherence to international law, though they tread lightly to avoid choosing sides. Vietnam and Laos are interesting stakeholders: Vietnam historically leans towards Cambodia (due to their alliance and Vietnam’s distrust of a strong Thailand), and Laos – sharing a border with both disputants – has stayed silent but is likely concerned about spillover if fighting nears Laos’ tri-border area. Laos and Vietnam may quietly coordinate to support a narrative favorable to Cambodia at ASEAN forums, given their close political ties. Conversely, Singapore, Philippines, and Indonesia prioritize regional stability and might support a neutral mediation. Notably, Indonesia, having mediated in 2011, offered at the time to send observers; former Indonesian FM Marty Natalegawa publicly commented that ASEAN should not “repeat the mistake of doing nothing.” Still, unless Thailand and Cambodia specifically invite ASEAN in, the bloc remains sidelined.

Implications for ASEAN: The crisis is exposing ASEAN’s lack of a conflict-resolution mechanism. Some commentators within ASEAN are using this to argue for revamping ASEAN’s approach (e.g. majority voting in such cases, or an empowered ASEAN Troika to mediate). Right now, ASEAN is in “paralysis”, which corresponds to one of our scenarios. There is a risk that if one side becomes unhappy with ASEAN’s passivity or perceives bias, it could affect ASEAN unity in other areas (for instance, Cambodia in 2012 blocked an ASEAN joint communiqué over the South China Sea to please China; similarly a future Thai or Cambodian chairmanship could be problematic if grudges remain). For now, ASEAN’s most visible role has been via the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ meeting where China’s Wang Yi made his mediation offer. It’s telling that it was on ASEAN sidelines that extra-regional powers engaged – which somewhat sidelines ASEAN itself.

In summary, ASEAN as an actor is presently a background chorus urging peace. If the situation worsens, ASEAN might appoint a Special Envoy or convene an emergency summit. If it remains stalemated, ASEAN will likely keep lines open but avoid formal intervention. Each member state’s stance is colored by its own politics: e.g., Myanmar’s junta (though largely isolated in ASEAN right now) would actually sympathize with Cambodia’s defiance (given Myanmar’s own issues with international criticism) and will not want ASEAN setting any precedent of intervention. The Philippines and Indonesia, dealing with their own territorial issues, are cautious but could push for at least an ASEAN statement so the organization isn’t completely embarrassed. Malaysia as current chair will likely continue behind-the-scenes shuttle diplomacy.

ICJ (International Court of Justice) & Legal Avenues: The ICJ looms large due to its history in Thai-Cambodian disputes. Cambodia clearly sees the ICJ as a favorable venue – it famously won the 1962 case over Preah Vihear temple, and in 2013 the ICJ’s clarification of that judgment effectively handed Cambodia a small additional parcel of land around the temple. In the current crisis, Cambodia’s leadership has signaled intent to seek an ICJ ruling on the new contested areas (like the 4.6 sq km around Preah Vihear still not demarcated, or the area around Ta Moan Thom). In June, Hun Manet instructed his legal team to prepare a case, and Cambodia’s UN Ambassador sent a letter (June 16) invoking “prevention of armed conflict” at the UN – possibly laying groundwork for an ICJ referral via the UNGA. However, Thailand’s stance is a roadblock: Thailand withdrew its blanket consent to ICJ jurisdiction in 1960 (right after losing Preah Vihear) and has explicitly reminded the UN that it “will not give consent to any attempt to initiate proceedings [at the ICJ] unilaterally.”. Thailand cites the 2000 Thai–Cambodia MOU on border demarcation, which commits both to negotiate bilaterally and not seek third-party adjudication while talks are ongoing. From Thailand’s legal perspective, Cambodia going to the ICJ violates that MOU’s Article VIII. Thus, unless Thailand reverses course, any ICJ case would require a jurisdictional basis that Thailand accepts – which it currently does not.

If by some diplomatic magic both agreed to ICJ arbitration, what then? The ICJ could indicate provisional measures (like an order to cease fire and withdraw to certain positions) while it examines the merits. A formal case could take years, but even a mutual agreement to go to court would instantly cool tensions (hence our scenario of legal de-escalation). Right now, that seems remote given Thai resistance.

UN and International Law: Beyond the ICJ, international law is invoked in multiple ways:

In sum, international legal institutions have been invoked but not yet deployed. The ICJ remains a theoretical avenue; the UN (General Assembly or Security Council) has been used as a platform to exchange letters, but no resolutions. One can foresee if fatalities mount, perhaps an emergency UNSC meeting could yield a statement urging ceasefire (as happened in 2011 where the UNSC called for a permanent ceasefire around Preah Vihear). ASEAN’s Treaty of Amity obliges peaceful resolution, but it has no enforcement arm – however, it could be cited if, for example, this goes to an ASEAN High Council (a conflict resolution body in ASEAN’s founding documents that has never been used).

Overall, international law is a battleground for narrative and a potential solution mechanism. Cambodia is leaning into it; Thailand is wary. The strategic use of law – whether to justify actions or to seek arbitration – will significantly shape diplomatic outcomes. If momentum builds for an ICJ case or UN mediation, that could freeze the conflict. Conversely, if both sides continue to lawyer their positions only to score points (as in the UN letters) while fighting continues, law remains just another front in the conflict.

Border Populations & Civil Society: The people living along the Cambodia-Thailand border are among the most immediately affected stakeholders. In Thailand’s northeast provinces (like Surin and Sisaket), many local communities are ethnically Khmer or Lao in origin and have historically interacted closely with their Cambodian neighbors through trade and family ties. The conflict has abruptly torn these ties – markets like Rong Kluea market near Aranyaprathet and the casinos of Poipet are shuttered, and cross-border marriages or families are separated by the closure. Civilians have been forced to evacuate en masse on the Thai side; in Cambodia, information is scarcer due to state-controlled media, but anecdotal reports speak of villagers in border districts like Choam Ksan (Preah Vihear) relocating further inland for safety. Civil society groups in both countries are constrained in their response: Thai human rights NGOs have cautiously called for humanitarian corridors and de-escalation, but they must balance this with the surging nationalist mood (anything perceived as too sympathetic to the other side could invite public backlash). In Cambodia, independent civil society has been largely muzzled under Hun Sen’s long rule – thus, few domestic voices publicly question the government’s hard line. However, Cambodian NGOs (particularly those focused on demining and development) quietly worry that the conflict will divert resources away from desperately needed economic development and landmine clearance (Cambodia was on track to declare itself landmine-free by 2025, a goal now jeopardized by new hostilities).

Media and Public Sentiment: Media on both sides are fanning patriotic sentiment. Thai mainstream media, even those critical of the government, have rallied around the flag, extensively covering Thai civilian suffering and the heroism of Thai soldiers. Social media in Thailand is filled with both patriotic fervor and conspiracy theories (e.g. unverified claims that Cambodian soldiers committed atrocities or that Thai opposition figures are “siding” with Cambodia – a spillover of internal politics). Cambodian state media portrays Thailand as the bully reviving Siam’s old aggression, reinforcing narratives of historical grievance. There were initial reports of small anti-Thai rallies in Phnom Penh after the May clash, with protesters burning Thai flags, though authorities quickly corralled them (likely to maintain a controlled image). Likewise in Thailand, a few ultra-nationalist groups have staged gatherings urging the government and army to take even stronger action, some even invoking the Thai monarchy’s role historically in defending territory.

Religious/Cultural stakeholders: An interesting civil society angle is the role of Buddhist monastic communities and UNESCO. Both countries share Theravada Buddhism, and monks on either side have sometimes acted as advocates for peace. In early July, Thai and Cambodian monks held joint prayer ceremonies (virtually) for peace, according to regional interfaith groups, emphasizing common religious heritage over conflict. Additionally, UNESCO, which designated Preah Vihear Temple as a World Heritage Site, has expressed concern that fighting could damage cultural heritage (as it did in 2011 when parts of the temple were scarred by shelling). UNESCO’s appeals add moral pressure to spare the temples from harm, resonating with civil society that values cultural preservation.

Transnational Crime and Business Interests: Oddly, a stakeholder group here are those involved in the illicit economies straddling the border – notably online scam syndicates and casino operators in places like Poipet and Sihanoukville. These groups thrived on porous borders and cross-border corruption. With the border sealed and both governments citing crackdowns on online scams (often run by Chinese syndicates using Cambodian bases and Thai victims), these criminal networks are disrupted. Thai law enforcement recently raided businesses linked to a Cambodian tycoon (senator Kok An) accused of running scam call centers. It’s notable that Thailand tied this to the border dispute, as if to say Cambodia harbors criminals attacking Thais online. This has brought an unusual set of actors (cyber-criminal rings) into the fray – and indeed China’s interest in “eradicating the tumor” of such crimes aligns here. In effect, the conflict is being used by Thai authorities to justify actions against these illicit networks (a side benefit for Thai law and order), while Cambodia’s image suffers from being seen as a haven for crime. Legitimate businesses, such as Thai manufacturing firms that relied on Cambodian workers or raw materials, are also stakeholders – associations of Thai exporters have quietly lobbied Bangkok to find a quick resolution or at least allow some trade corridors, as warehoused goods pile up. On the Cambodian side, small farmers who export cassava and mangoes to Thailand have lost their market due to the fruit ban and border closure – some Cambodian civil society voices worry this will impoverish border communities and possibly push them into illegal smuggling to survive.

Monarchy and Elite Circles: In Thailand, the monarchy is a critical (if behind-the-scenes) stakeholder. King Vajiralongkorn has not made any public statement, but on July 5, Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn (highly revered and known for her interest in Cambodia’s culture) publicly expressed concern for soldiers and even gave protective amulets to Thai troops at the border. This symbolic act – widely reported – effectively gave the royal endorsement to the military’s cause and boosted morale. It suggests the palace is paying attention and likely supports a tough defense of Thai territory. Royal influence can also restrain extremes; if the King signaled disapproval of all-out war, the army would heed it. Cambodia, a republic, doesn’t have a monarch, but it does have the Hun family which functions almost like a dynastic elite. Their cohesion means no elite faction in Cambodia is dissenting from Hun Manet/Sen’s approach. If anything, some in the CPP elite who lost business from the border closure might privately push for a settlement, but given Hun Sen’s dominance, such voices are muted.

In summary, civil society and peripheral actors mostly underscore the human and cultural cost of the conflict and occasionally serve as moderating voices. Yet, in the wave of nationalism, their influence is limited. Their importance may grow if the conflict stalemates and humanitarian issues (displacement, livelihoods) become more pressing – at that point, public fatigue with the conflict could set in, pressuring leaders to compromise. But as of now, nationalist fervor, stoked by state narratives on both sides, means civil society calls for peace struggle to be heard over the drumbeats of war.

This matrix of actors highlights that the Cambodia-Thailand crisis is not merely a two-party spat, but a nexus of regional and internal forces. Each actor – from superpowers to local villagers – plays a role in either exacerbating or alleviating the conflict. Understanding their motivations clarifies why the situation has evolved as it has, and where leverage for resolution might lie (for instance, through Chinese diplomacy or grassroots desire for peace).

Building on the actor assessments and conflict dynamics, we detail the five scenarios previously introduced, explaining why each is assigned its probability and exploring their specific outcomes in greater depth. These scenarios are not exhaustive but cover the most plausible trajectories for the next 1–3 months, given current indicators.

Description: In this scenario, diplomatic pressure and backchannel negotiations convince both Thailand and Cambodia to halt hostilities and let international law address the dispute. This could happen if, for example, China and ASEAN jointly lean on the two governments to agree to an ICJ-mediated ceasefire. The mechanism might involve Thailand softening its stance on ICJ involvement (perhaps under the face-saving notion of a “provisional technical adjudication” rather than a full sovereignty ruling) and Cambodia pausing its military forward deployments as a goodwill gesture. Both armies would ceasefire and pull back from immediate collision points, creating a buffer zone overseen informally by monitors (which could be drawn from neutral ASEAN states or even UN personnel if mandated). Then, the legal process would kick in: Cambodia likely submits a formal application to the ICJ regarding the border dispute, and Thailand, albeit reluctantly, participates in proceedings given it agreed politically to this route.

Why 15%: This outcome, while highly desirable to avoid further bloodshed, faces significant hurdles – chiefly Thailand’s reluctance to trust the ICJ. The probability is not zero, however, because international pressure is mounting. If, say, China privately tells Bangkok that continued fighting will jeopardize Chinese investment and suggests ICJ arbitration as a solution, Thailand might yield (especially if internal political chaos makes them eager for a timeout). Also, historical precedent exists: in 2011, facing UNSC attention, Thailand and Cambodia accepted an ASEAN/ICJ-involved arrangement (Indonesia’s observers and later the ICJ’s 2013 ruling). Already Cambodia has asked the ICJ to intervene, and if Thailand can find a way to frame legal arbitration as a patriotic move (e.g. “we will present our evidence to the world and prove our case”), it could become palatable.

Consequences: A “cooling-off” would likely freeze the military situation. Border areas would remain militarized but without active fighting – effectively a return to the uneasy calm of early 2023, but with international monitors on the ground. Civilians could gradually return home under assurances of safety. Trade might partially resume – possibly limited reopening of key checkpoints like Poipet–Aranyaprathet for goods, under observation that neither side moves troops through them. Humanitarian demining operations might be jointly undertaken in contested zones (a confidence-building measure and necessity if troops pulled back through potentially mined areas). Diplomatically, both countries would submit legal briefs to the ICJ. We might see a situation where the ICJ, acknowledging Thailand’s non-recognition of compulsory jurisdiction, brokers a special agreement between the parties to arbitrate certain boundary sections. The dispute would enter the slow, face-saving channel of legal resolution, taking it off the boil of daily headlines.

For Thailand, a positive consequence is buying time – it can focus on sorting out its internal leadership crisis while the border is “someone else’s problem” (the ICJ’s). For Cambodia, it validates their approach that international law supports them and gives domestic bragging rights that they brought Thailand to the world court. However, this scenario could also yield frustrations: legal processes are slow, and hardliners in both nations might accuse their leaders of “giving up sovereignty to foreign judges.” Managing nationalist narratives during the legal phase would be crucial – likely requiring constant reassurance that neither side surrendered territory by agreeing to talk. Nonetheless, casualty tolls would stop increasing, and both economies could start recovering. UN/ICJ involvement would also set a precedent in ASEAN that territorial rows can be solved peacefully, boosting rule-of-law norms regionally. In sum, while challenging to initiate, this scenario provides the most stable off-ramp, essentially internationalizing the problem to remove it from the battlefield.

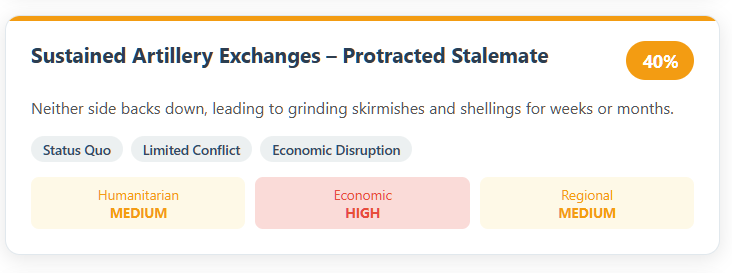

Description: This is currently the default trajectory absent new intervention. Here, neither side fully backs down, but neither escalates to all-out war beyond the border zones. The conflict becomes a grinding series of skirmishes and shellings that continue for weeks or months. After the intense clashes of late July, both militaries might adopt a tit-for-tat pattern: e.g., every few days, one side fires mortar or artillery rounds to test the other, drawing retaliation. Front-line units remain on hair-trigger alert, and localized commanders have de facto authority to open fire if they “feel threatened.” No major offensives are launched (no crossing of large troop formations into enemy territory), keeping the conflict contained geographically to contested strips of land. Diplomatically, talks remain frozen – there might be occasional ceasefire talks at the general-officer level, but they yield no lasting agreement. The status quo of hostility continues through the next 2–3 months, with occasional flare-ups that kill a handful of soldiers or civilians, but then subside again.

Why 40%: This scenario is quite likely because it reflects a continuation of what is happening now: both sides seem willing to endure a limited conflict to avoid making concessions. Thailand can sustain a border standoff given its larger economy and military, and Cambodia, though underdog, has domestic political will to keep fighting in small doses. Unless something forces their hand (like an unbearable economic hit or a game-changing diplomatic move), inertia leads to this protracted conflict. Historically, Thailand and Cambodia had similar multi-month confrontations in 2011 – that year saw sporadic fighting in February, April, and again in July before petering out. A similar trajectory in 2025 is plausible, with skirmishes flaring then quieting repeatedly without formal resolution.

Consequences: The humanitarian and economic toll will worsen steadily. We anticipated over 100,000 displaced persons – indeed, if Thai evacuation zones expand or if Cambodian civilians also flee border villages, the numbers could climb into six figures. These internally displaced people would need sustained support, straining local governments. Trade will remain largely halted. The ainvest financial analysis noted $5.4B in bilateral trade (2024) is disrupted; as the stalemate drags on, that disruption becomes effectively permanent for 2025. Border economies would crash: Poipet’s casino economy and Thai border towns reliant on day traders would be ghost towns. Legitimate commerce would reroute (Thai goods to Cambodia via Laos or sea, as mentioned with 30% higher cost), meaning higher prices in Cambodia and lost profits in Thailand. Diplomacy under stalemate likely involves a lot of finger-pointing at ASEAN and UN meetings, but no side budges. Both might agree to let some third-party monitoring (perhaps ICRC or ASEAN observers) in for humanitarian reasons, but not for ceasefire enforcement.

Crucially, a long stalemate would cause internal strains: in Thailand, public opinion might sour if Thai civilians or soldiers keep getting hit. The Thai Army could then feel pressure to escalate (which could tip into scenario 3). Or conversely, Thai public could tire of war-footing and demand a deal (especially if the Thai economy, which is larger, starts feeling the drag in border regions or if investor confidence dips countrywide due to conflict risk). In Cambodia, a poor country, sustaining a military mobilization for months has costs – budgets would be reallocated to defense, possibly at the expense of social programs. Shortages of Thai goods (fuel, construction materials) could slow Cambodian economic activity, though they’d try to substitute from Vietnam/China.

A silent effect: landmines and UXO (unexploded ordnance) contamination would increase if exchanges continue. Each bout of shelling leaves behind dud explosives, exacerbating the legacy mine problem. This could set back development for years in affected areas.

Internationally, this scenario is one of frustration: ASEAN’s reputation suffers for each week of inaction; foreign investors might label both countries as higher-risk (with Cambodia risking more, as FDI might hesitate if war risk persists). Over time, if stalemate continues into a truly frozen conflict by, say, 90 days out, some external mediator might step in to break the deadlock (i.e., scenario 1 or 4 could eventually branch from stalemate out of necessity). But within the 30–90 day frame, scenario 2 could simply be an unpleasant holding pattern with no decisive victor, just cumulative pain. This is why it holds the highest probability – it requires no bold moves, just the absence of resolution. Unfortunately, that means the border residents and bilateral relations will continue to bleed slowly, with none of the deeper issues solved.

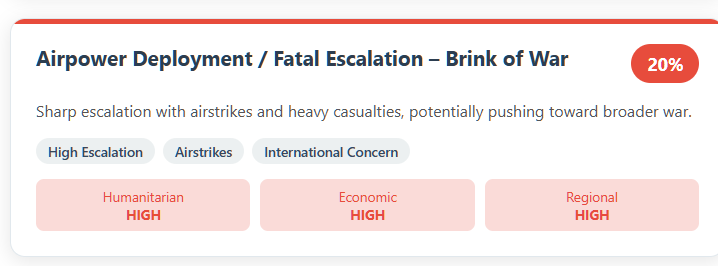

Description: This scenario represents a sharp escalation from the current situation, potentially pushing the conflict to the brink of a broader war. It could be triggered by a high-casualty incident or miscalculation. For instance, imagine in early August, a particularly deadly clash occurs – say a Cambodian rocket strike hits a Thai military camp or command post, causing many fatalities, or Thailand conducts a second F-16 bombing run and accidentally kills a Cambodian battalion commander or dozens of troops. Such an event would create domestic outrage and demands for retribution. In this scenario, Thailand might respond by significantly expanding its use of force: conducting multiple airstrikes deep into Cambodia against military targets (ammo depots, troop columns), possibly even using precision-guided munitions on Cambodian base infrastructure. Cambodia, facing heavier losses, might invoke its mutual defense understandings with allies like China or Vietnam, or more desperately, employ asymmetrical tactics – for example, deploying long-range artillery near civilian areas to deter Thai strikes (essentially using human shields), or covertly supporting insurgent activities in Thai territory (e.g. encouraging Thai Malay-Muslim insurgents in the south to divert the Thai military’s attention – a stretch, but desperation could breed dangerous games).

This escalation would likely prompt international panic. ASEAN’s silence would break – countries would call emergency meetings. The UN Security Council would almost certainly convene if airstrikes and heavy casualties continue unabated. News cycles globally would compare the situation to other regional wars (the op-ed we saw already likened it to Kashmir or Korea DMZ skirmishes).

Why 20%: While neither side wants a full-scale war, the chances of stumbling into one are not negligible. The use of heavy weaponry has already begun; the introduction of airpower by Thailand is a slippery slope. If Cambodia, feeling cornered, shoots down a Thai jet (they’d need external help or luck for that, but possible if MANPADS or AA guns score a hit) – that could kill a Thai pilot, a dramatic escalation. Or, a direct confrontation at sea (they also have an unresolved maritime boundary; a naval encounter in the Gulf could flare). Given the level of forces mobilized and nationalist fervor, a single incident could ignite a rapid escalation beyond planned limits. We assign 20% – not the base case, but a real risk especially if stalemate (scenario 2) feeds frustration or if command-and-control slips (e.g., a local Thai commander might retaliate excessively for losing men, or a Cambodian field unit might not get the memo to hold fire during a delicate moment).

Consequences: If this scenario unfolds, it could mean dozens or even hundreds of combatant deaths and possibly civilian casualties in the double or triple digits. Refugee flows could start: Cambodians might flee deeper into Cambodia or even into Laos/Vietnam if they fear a Thai onslaught; Thais in border provinces might flood evacuation centers in provincial capitals. ASEAN would fracture because members would not agree on a response – likely a split where maybe Vietnam and Laos back Cambodia’s narrative, while others lean toward Thailand or call both “brothers” to stop (i.e., a meaningless plea). ASEAN’s inability to act in unity would effectively hand conflict resolution to the great powers. China might step up more forcefully – perhaps deploying a naval flotilla to the Cambodian coast as a show of support, or flying in air defense systems (a bold move, but if Cambodia is getting bombed and asks for SAMs, China could deliver them under cover of “humanitarian assistance”). The U.S. and its allies, on the other side, would vocally support Thailand’s right to defend itself, and might increase intel-sharing or even quietly deploy advisors (the Thai-U.S. security relationship, dormant in recent years, could reawaken under a treaty obligation if Thailand formally cites the 1954 Manila Pact or 1962 Rusk-Thanat communiqué to request aid against aggression). In essence, we could see the conflict internationalize into a proxy standoff: China helping Cambodia, the U.S. (and perhaps Japan or Australia) aiding Thailand diplomatically or with materiel.

Domestically in Thailand, a “rally-round-the-flag” military takeover becomes plausible. If the civilian government is seen as ineffective in war, the Thai military (already predisposed to coups) might assume direct control “to prosecute the war more effectively.” They could impose censorship, martial law, and mobilize reserves. In Cambodia, Hun Sen could declare some formal role (even though he’s “retired,” in crisis he might step in as “Supreme Military Commander” or such, which would be popular internally). Cambodia might also fully sever any remaining ties – e.g., cut the Mekong river water flow from a dam to Thailand if possible (not likely significant, but symbolic measures).

Media blackouts would be instituted: Thailand would likely restrict reporting from the front, and Cambodia already tightly controls it. This leads to fog of war – rumors and propaganda dominate. One side might attempt a false-flag operation to justify further escalation (a noted wildcard): e.g., a mysterious explosion in a Thai border town blamed on Cambodian saboteurs could be used to drum up support for war mobilization.

Ultimately, because neither country truly has the appetite or capability for a prolonged full war, this scenario might burn hot but short. Perhaps after some days of intense escalation, international intervention (by UNSC or major powers) compels a ceasefire. But the damage would be done: ASEAN’s veneer of unity would be shattered, trust between Thais and Cambodians would be at generational lows with memories of fatalities, and both economies would be significantly hurt (markets would fall, investors pull back).

This scenario, while worst-case in human terms, could ironically force a quicker resolution because the international community might step in decisively to stop an ASEAN war. For instance, the UNSC could pass a resolution deploying observers or mandating a ceasefire line. But relying on that is dangerous. The bottom line is this scenario must be avoided, yet with heavy weapons in play and high emotion, it is a real possibility if current restraint falters even briefly.

Description: In this scenario, China takes a proactive mediation role and succeeds in negotiating a ceasefire accord by, say, late August. The process might begin with behind-the-scenes diplomacy: Chinese envoys meet separately with Cambodian and Thai leadership to hammer out basic terms (e.g., no further fighting, return to original positions, set up a joint working group for border demarcation talks, etc.). This could culminate in a summit in Beijing (or a neutral site like Kunming or Singapore) where Thai and Cambodian representatives, under China’s auspices, sign a ceasefire memorandum. ASEAN could be looped in for face-saving (maybe co-signed by the ASEAN Chair to give it regional legitimacy, even if China did the heavy lifting). The ceasefire wouldn’t necessarily solve the underlying border claims but would freeze the conflict.

A key component likely includes economic sweeteners – hence “carve-outs.” China might pledge new investment in Thailand or Cambodia as incentives. For instance, China could offer Thailand some infrastructure investment or access to Chinese markets as a goodwill for agreeing to the deal, and to Cambodia it could promise expedited development projects to offset losses from the border closure. Also, both sides might agree to re-open certain border crossings specifically for Chinese-funded projects or trade corridors (ensuring China’s economic interests resume even if other trade is limited). So essentially, China might carve itself a role as guarantor and beneficiary of the peace.

Why 10%: China has offered to help, but whether both sides trust China to be impartial is uncertain. Cambodia would leap at Chinese mediation; Thailand is more cautious, given its traditional alignment with the West and slight wariness of Chinese intentions. However, if Thailand’s relations with the U.S. remain lukewarm (they have improved recently but are not as tight as decades ago) and if ASEAN remains ineffective, Bangkok might consider China’s offer pragmatic. Another factor: by late August, Thailand’s internal politics might shift – if Paetongtarn’s fate is sealed (e.g., permanently removed and a new PM in place, possibly military-friendly), that new leadership might feel freer to cut a deal via Beijing to quickly stabilize the situation. We keep probability low-ish because Thailand accepting a major Chinese diplomatic role would mark a geopolitical tilt; it’s possible but not Bangkok’s first choice historically. Yet, the logic of “use whoever can stop this mess” could prevail.

Consequences: A China-brokered ceasefire likely entails immediate cessation of hostilities and perhaps a return to status quo ante positions (each side back to the positions held before May 2025). There might be a joint statement of respect for previously agreed principles (like reaffirming the 2000 MOU on demarcation and pledging to accelerate boundary talks). Monitoring could be interesting: China might position itself as a quasi-monitor, or push for a joint Thailand-Cambodia border observer mechanism (possibly with Chinese technical support). Unlike an ICJ resolution, this would be more of a political understanding than a legal one, so compliance would depend on ongoing Chinese engagement.

The freeze with economic carve-outs phrase suggests that even if political/diplomatic ties take time to normalize (they might keep ambassadors out for a while out of spite), they’d carve out exceptions to benefit each side’s economy. For example, Cambodia might resume importing Thai fuel (because China might quietly subsidize it or arrange a swap through a Chinese company, framing it not as direct Thailand-Cambodia trade but via a third party). Similarly, Thailand might allow certain exports like fertilizer or medicine to Cambodia on humanitarian grounds, which incidentally help Cambodian economy. They might also lift bans on media or travel quietly, to ease public life, even if formal relations stay downgraded for some time.

For China, the consequence is a huge diplomatic win. It would highlight that Western or UN efforts were secondary and that an Asian power resolved an Asian conflict. This could deepen Cambodia’s dependency on China – Phnom Penh would be more beholden to Beijing’s interests (potentially granting more favorable terms on Chinese projects, or allowing more security presence, e.g. at Ream naval base, as a thank you). Thailand might also drift closer to China after seeing Beijing’s effectiveness – or at least maintain a more balanced diplomacy between the U.S. and China.

One should note a potential side-effect: if China mediates but does so in a way perceived as favoring Cambodia (its close ally), it might sow seeds of resentment in some Thai circles that China “pressured” Thailand. That could complicate Sino-Thai relations down the road. To mitigate that, China would likely ensure Thailand also saves face in the deal – maybe including something like both sides agree to clamp down on transnational crime (a Thai objective) and Cambodia agrees to concrete actions on scam casinos, which Thailand can tout as a win.

In the ceasefire’s aftermath, a formal peace treaty or border agreement might still be distant – but the immediate crisis would be over. Military de-escalation would allow evacuees to return home, though likely with caution (some might not trust that the ceasefire holds initially). Diplomats would gradually return; perhaps in a few months, ambassadors quietly go back without fanfare, and by next year full relations resume. Trade would normalize faster given both economies need it.

Regionally, ASEAN might publicly “welcome” the ceasefire but privately many would note it was China, not ASEAN, that ended the conflict – a potential blow to ASEAN centrality. However, some might also breathe a sigh of relief that at least a conflict in their backyard ended. The U.S. and others would have to acknowledge China’s constructive role, possibly tempering criticisms of China (which Beijing would leverage in propaganda).

Overall, this scenario averts war and stops the suffering relatively quickly, at the cost of increased Chinese influence and a sense that regional security architecture has shifted. Given China’s already significant role in Cambodia and its growing ties with Thailand, this outcome is plausible if the conflict threatens to spiral or simply if China sees a chance to score a diplomatic victory.

Description: In this scenario, the conflict neither fully resolves nor continues at high intensity, but instead settles into a long-term frozen conflict. Essentially, Thailand and Cambodia would agree informally to stop major fighting (perhaps after a few more skirmishes scare both sides), but without any formal peace or external mediation. They simply fortify their respective positions and brace for a protracted standoff. Diplomacy remains broken – ambassadors don’t return, and public rhetoric stays hostile – but outright war is avoided by a mutual recognition that it would be too costly. However, no one compromises on the underlying issues, so the border remains a tense militarized zone indefinitely.

Why 15%: This is plausible if both governments prefer status quo over compromise. Suppose months pass and domestic focus shifts (Thailand might get a new government who is more nationalist; Cambodia might be content that it stood firm). ASEAN’s paralysis continues and no other mediator steps in (or attempts fail). The two sides might just leave things as they are – a grudging ceasefire born not of agreement but of exhaustion. Essentially, it’s scenario 2 (stalemate) extended beyond 90 days with institutionalization. We give it 15% because while it’s possible, maintaining such a cold standoff is costly; often pressures (economic, international, domestic) eventually force a resolution or return to conflict. But some disputes do freeze for years (e.g. India-Pakistan at Siachen Glacier, or the Thailand-Laos border dispute in 1980s that took years to resolve). If the flashpoints (temples) can be physically separated by presence of troops (each side just sits on its hill), this could drag on.

Consequences: Borders militarized indefinitely – expect permanent deployment of Thai heavy units (maybe even relocating an armored or artillery brigade to the border), and Cambodia keeping a significant portion of its small army in the northwest front rather than other duties. Demarcation talks remain stalled, so the fundamental disagreement persists for future flare-ups. Both countries might start viewing each other as persistent adversaries; defense planning and military procurement will adjust accordingly (the ainvest report noted a defense spending surge of 20% already; entrenched conflict would harden those budgets, e.g., Thailand might invest in more tanks or drones for border defense, Cambodia in more rockets or air defenses). This could indeed trigger a mini arms race in Southeast Asia, eroding trust region-wide.

Economically, some border trade might reopen out of necessity, but under tight controls. Smuggling would likely flourish as official crossings remain intermittent – black markets for goods would emerge, enriching corrupt officials and criminal networks. Legitimate trade might find semi-legal channels (for example, goods routed through Laos or Vietnam then into the other country to circumvent direct trade bans).

The social fabric of the border communities would change: fences and walls might literally go up. For instance, Thailand could build more border fences or even minefields (though treaty-bound not to, they could use other obstacles) to stop incursions. Cross-border marriages or tourism (Cambodians visiting Thai hospitals, Thais visiting Angkor, etc.) would drop to near zero, fostering mutual ignorance and prejudice over time.

On the diplomatic front, ASEAN would suffer a huge dent. It would show that two members are practically in a cold conflict and ASEAN could do nothing – expect more calls from analysts to reform ASEAN’s conflict resolution mechanisms (perhaps a wake-up call that gets ignored due to consensus rule). Unity on other issues could erode; Cambodia or Thailand might block each other’s initiatives in ASEAN out of spite. In the long run, that could lead to an ASEAN that is split into camps or just ineffective on anything contentious (even more than now).

Another wildcard here: false peace – with no resolution, each side might at times break the quiet. So this frozen hostility might not be perfectly frozen; there could be occasional sniper shots, arrests of “spies,” propaganda blasts over loudspeakers – reminiscent of the DMZ between the Koreas where it’s mostly quiet but with intermittent provocations. Over years, such a situation might produce its own status quo normalization: younger generations in Thailand and Cambodia might grow up accepting that “the border is closed and hostile.” That’s a sad outcome for regional integration hopes.

Internationally, an entrenched conflict that’s low-grade might be largely ignored by major powers after initial attempts. The UNSC likely wouldn’t keep it on active agenda if no big clashes occur. The ICJ route would be abandoned due to Thai refusal, so that lingering legal dispute just festers. One could foresee this eventually being resolved maybe by a future leadership change or external shock – but within our scenario timeframe (next 3 months to a year), it just stays frozen.

So, the difference between scenario 2 and 5 is basically timescale and formalization: scenario 2 is a short-term sustained clash that could still shift, scenario 5 is that pattern solidifying into a new normal. The probability is moderate – it unfortunately aligns with ASEAN’s historical habit of “sweeping disputes under the rug” until they occasionally flare again.

In essence, scenario 5 is a failure of conflict resolution, yielding a lose-lose: no war, but no peace, just enduring tension. It’s a bit like the Kashmir situation (referenced in WP op-ed) or other unresolved borders, minus heavy daily fighting but with constant military presence and risk.

These scenario analyses underscore that while immediate all-out war was averted in the first weeks, the situation remains highly fluid. The probabilities may shift if certain indicators change (e.g., if Thailand’s political crisis abates in favor of a hawkish government, scenario 3 risk might increase; if an international initiative gains traction, scenario 1 or 4 could rise). As of now, a prolonged yet contained conflict (scenario 2) appears most likely, but stakeholders must be mindful of the not-insignificant chance of a sudden escalation or the peril of letting the conflict ossify. The next section will map out the legal and diplomatic risks inherent in these scenarios and identify key decision points.

The Cambodia–Thailand border crisis not only plays out in jungles and villages, but also in courtrooms, treaty halls, and diplomatic corridors. This section maps the legal and diplomatic dimensions of the conflict – outlining current treaty obligations, potential international interventions, and the risks of legal breaches or diplomatic missteps.

In conclusion, the legal and diplomatic mapping shows multiple frameworks that both restrain and complicate the conflict:

The key risks in this realm are: continued violation of treaties (leading to loss of international goodwill), failure to communicate (leading to escalations), and letting big-power politics overtake regional solutions (which could make the conflict a pawn in larger rivalries).

Mitigating these risks would involve reactivating communication channels (maybe via intermediaries), abiding by humanitarian law (to avoid global backlash), and possibly agreeing to some form of impartial monitoring or arbitration to rebuild trust. The next section on economic disruption will show another angle of pressure that might eventually impel diplomatic compromise.

The border crisis has already delivered a shock to both countries’ economies, especially at the local level. This section projects the economic fallout if the situation continues, examining trade, investment, and livelihoods – essentially, how the conflict rattles an intertwined regional economy and what the short to mid-term outlook is under current scenarios.

Bilateral Trade Collapse: Prior to the crisis, Thailand and Cambodia enjoyed robust cross-border commerce – in 2024, bilateral trade was valued around $5.4 billion. Thailand exported roughly $4+ billion worth of goods (petroleum, consumer products, construction materials, etc.) to Cambodia and imported about $1–1.5 billion (largely agricultural produce and some semi-processed goods). As of mid-2025, this trade is in freefall. The closure of key border checkpoints (such as Poipet–Aranyaprathet in Sa Kaeo and Osmach–Chong Chom in Surin) has effectively shut down formal trade routes. According to one analysis, these closures disrupt virtually the entire $5.4B trade flow, with Thailand’s exports to Cambodia particularly hit (Thailand traditionally runs about a $3B surplus).