Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

It is a critical security practice to secure elevated vantage points so a security team’s protectee does not get assassinated. This challenge will only worsen as drone-borne attacks become more common. The abject failure to secure vantage points at the Charlie Kirk event, similar to that which occurred when Donald Trump was almost assassinated in Butler, PA, embodies a recurring failure of both public and private protective services.

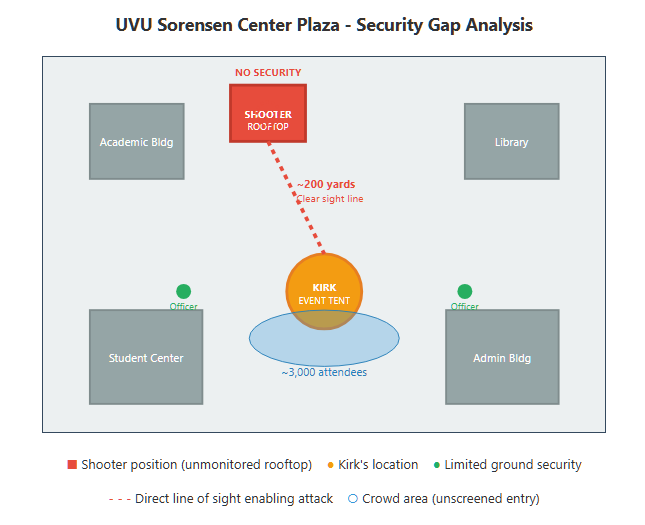

Charlie Kirk – a 31-year-old conservative activist and CEO of Turning Point USA – was addressing a crowd of roughly 3,000 at an outdoor campus courtyard (the Sorensen Center plaza at Utah Valley University) around noon on September 10, 2025. He sat under a white event tent emblazoned with “The American Comeback Tour” slogans, taking audience questions in a “Prove Me Wrong” open debate format. At approximately 12:05 PM, as Kirk was responding to a question about mass shootings, a single gunshot rang out. Eyewitnesses and video confirm that Kirk was struck once in the neck mid-sentence. He immediately recoiled, raising his right hand toward the left side of his neck as a large volume of blood gushed from the wound. Kirk collapsed backwards off his chair almost instantly, lying motionless as panic erupted in the crowd. Attendees at first didn’t recognize the sound – some thought it was a confetti pop or prank – but within seconds realized it was a gunshot and chaos ensued. People screamed, ducked for cover, then began stampeding away once it seemed no second shot was forthcoming. Within moments, Kirk’s private security detail and event staff rushed to his aid, applying pressure to the wound as best as they could before evacuating him to a hospital. Despite rapid medical intervention, the injury proved fatal – Kirk was pronounced dead shortly thereafter, news that President Trump publicly confirmed that afternoon.

In the immediate aftermath, numerous videos from spectators’ phones circulated online, providing multiple angles of the shooting. These open-source videos captured slightly different perspectives of Kirk’s final moments and fueled confusion about what exactly occurred. One particularly graphic clip (widely shared on X/Twitter before social platforms began age-restricting it) showed a direct view of Kirk being hit: his body jolts and blood spurts violently from his neck wound, eliciting gasps from onlookers. Another video, taken from a different side, showed the moment of impact in slow motion – replayed in a loop stopping just before the blood is visible, presumably to avoid graphic content. A third angle filmed from Kirk’s left captured the audio of the exchange, with Kirk ironically discussing gun violence just as the shot rang out. In this clip, the whip-crack of the rifle and a shocked voice yelling “Oh my God!” are heard as Kirk crumples. These variations led to discrepancies in perception: some viewers initially questioned if Kirk tried to stand or speak after being shot, since one video’s framing showed him momentarily upright (likely a reflexive recoil) before collapsing, whereas another angle showed him immediately floored and limp. Similarly, reports of the bleeding differed – witnesses on-site uniformly described “blood pouring” or “gushing everywhere” in a “waterfall” from Kirk’s neck, but traditional media coverage was far more restrained, often not showing any blood on camera. Mainstream outlets either blurred Kirk’s upper body or cut away after the shot, focusing instead on the crowd’s reaction. This gatekeeping by news organizations, however, mattered little in practice – millions had already seen the uncensored footage across social media within hours, illustrating how in the smartphone era the most graphic details reach the public instantly, regardless of media caution.

Despite the brutal outcome, there had been no explicit warning of a sniper attack prior to the event. However, Kirk’s visit to the UVU campus was not without controversy or potential risk signs. In the week leading up to the speech, campus opposition had been vocal: an online petition garnered nearly 1,000 signatures urging the university to cancel Kirk’s appearance, accusing him of espousing views contrary to “values of understanding, acceptance, and progress” on campus. The event proceeded in the name of free speech – the university cited its commitment to open dialogue – but the polarized atmosphere meant heightened emotions. Kirk himself had noted the turbulence, posting on X: “What’s going on in Utah?” alongside clips about the controversy. On the day of the event, there were no significant physical altercations or protests reported at the venue (crowds were reportedly “super positive” and pro-Kirk overall). There also were no security alerts or specific threats detected by authorities beforehand – Utah’s governor later said no motive was immediately known, and officials hadn’t flagged any credible threat actor in advance. In hindsight, the only hints of danger were the general climate of political vitriol and the fact that Kirk’s appearances often drew criticism. Unfortunately, any online chatter or extremist intent that may have presaged the attack was either absent or missed by intel, and the shooting seemingly came without warning from a distant quarter. It underscores the difficulty of threat prevention in an era when a lone assailant with a rifle can strike from afar without telegraphing their plans.

In the chaotic minutes following the shot, law enforcement initiated a full lockdown of the campus and surrounding area. Campus police and Orem city police swept buildings, instructing students and staff to shelter in place until officers could escort them out safely. Initial reports were conflicting: Utah’s Governor Spencer Cox announced a “person of interest” was in custody not long after the shooting, but state Public Safety Commissioner Beau Mason contradicted this, stating the suspect was still at large. It emerged that police briefly detained an individual who was near the scene, but he was released after interrogation when it was determined he did not match the shooter caught on CCTV (though he bizarrely was later booked for obstruction of justice). Update (September 16, 2025): The man who falsely confessed to shooting Charlie Kirk at the scene, George Zinn, has now been charged with possession of CSAM. The FBI joined the investigation on-site, setting up a tip line for leadS. As evening fell, FBI Director Kash Patel clarified that a “subject” earlier taken into custody had been released and the investigation was ongoing. Authorities revealed they had retrieved security footage suggesting the shot came from an elevated position on campus, “potentially from a roof,” and that the suspect was dressed in all dark clothing. This led to an intensive search of campus rooftops and nearby buildings. By night, UVU officials declared the campus “all-clear” once evacuations were complete and no further threat was detected. The attack sparked immediate bipartisan condemnation nationwide, with public figures from the President and Utah’s governor to opposition lawmakers denouncing the “political assassination” of Kirk and calling for unity against violence. Nevertheless, the day ended with the shooter still unaccounted for, raising unnerving questions about how such a brazen attack could succeed in broad daylight and what security lapses may have enabled it.

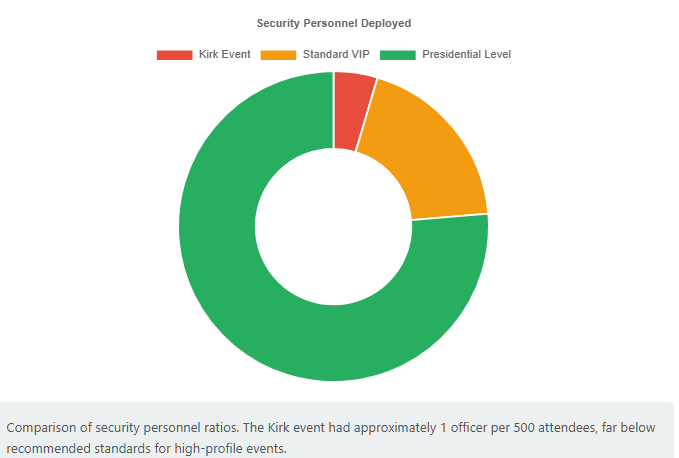

The protective posture at the Kirk event appears to have been relatively minimal, especially when compared to the security that high-ranking officials receive. Utah Valley University’s police chief noted that six officers were assigned to the event, including a few plainclothes officers in the crowdabcnews.go.com. These were likely a mix of campus police and local law enforcement. Kirk, as a private citizen and activist, did not benefit from Secret Service or federal protection; instead, his own organization and the host venue had arranged security. Witnesses observed virtually no special screening procedures for attendees: “there were no metal detectors… and no one inspecting bags,” one attendee in the fourth row recalled, criticizing the lax control over who could enter with what. In practice, the event was open-air and freely accessible – attendees just walked up to the outdoor plaza without passing through any magnetometers or pat-downs. Kirk did have a personal security detail on scene (as evidenced by them quickly whisking him away after he was shot), but their focus would have been close protection (i.e. guarding Kirk’s immediate person and responding to crowd disturbances or direct attackers). No perimeter expansion or pre-screening beyond the immediate tent area was implemented. This light footprint likely stemmed from viewing the campus event as a standard speaking engagement rather than a high-risk rally – an assumption that, in hindsight, proved tragically mistaken.

Critically, elevated positions overlooking the event were not secured or monitored, creating a gaping vulnerability. The courtyard where Kirk spoke was encircled by campus buildings and possibly parking structures, any of which could serve as a sniper hide. According to Utah DPS Commissioner Beau Mason, CCTV footage later confirmed that the shot was fired from a location on campus – “potentially from a roof” – at some distance from the crowd. Indeed, one student witness estimated the shooter’s position was around 200 yards away from Kirk, at an angle to the left of the stage. This implies the attacker had stationed themselves on a rooftop or high window roughly 180–200 meters off – a distance easily within effective range for a rifle, but far beyond what on-ground officers were actively watching. No law enforcement or security personnel were posted to that roof or others nearby. There was also no mention of spotters with binoculars scanning upper-storey windows, nor any requirement that nearby buildings be vacated or their access locked down. In effect, the shooter had unimpeded access to a “clear line of sight” on the target from a hidden, elevated perch. This is a stark deviation from VIP security best practices. For comparison, the U.S. Secret Service typically deploys specialized Counter Sniper (CS) teams to every major protectee event – these are highly trained marksmen whose sole job is to occupy vantage points and surveil other high ground, neutralizing any shooter before they can fire. Secret Service doctrine has long recognized that rooftops, balconies, and windows command the killing ground; therefore, agents coordinate with local authorities to secure those positions or place their own snipers there. In Kirk’s case, however, being a non-government VIP, such measures were absent. The shooter exploited this gap, accessing a rooftop with a firearm undetected. It appears even basic precautions like stationing an officer at the rooftop access door, or scanning the roof with binoculars, were not done. The result was that an assailant could set up a firing position with impunity, turning the entire venue into a shooting gallery from above.

The physical setup of the event further compounded the risk. The Sorensen Center courtyard is an open area on campus, surrounded by multi-story buildings of the university. Photographs after the shooting show a tent and podium set up in essentially a semi-enclosed plaza, overlooked by the windows and roofs of adjacent campus facilitiesopb.orgopb.org. In essence, Kirk was positioned in a “fishbowl”: highly visible to any elevated observer in the vicinity, but with little overhead protection. There were no sniper screens or overhead cover – just a small canopy tent offering no ballistic protection. Additionally, the perimeter was porous. People could approach the event area freely from multiple directions (there were likely several access points on campus), and beyond the immediate crowd no secondary outer perimeter was established. This means a person could move into a building a block away with a long gun and find a window or roof access without ever encountering a checkpoint. The venue’s architecture – an open-air gathering spot amid tall campus buildings – was inherently susceptible to a high-angle attack. A competent security advance would have identified those surrounding structures as hazards (in protective security terms, they create fields of fire and observation that must be controlled). Best practice in such a scenario might be to choose a different location (e.g. an indoor auditorium or a more isolated outdoor area) or to mitigate extensively (sweep and seal off rooftops, deploy counter-snipers, use overhead surveillance). Unfortunately, none of those mitigations were evident at this event. The shooter had both elevation and standoff distance, a deadly combination that meant even a large police presence on the ground level would have limited ability to spot or stop the attack once it began. Indeed, an officer on the ground can hardly even detect a threat on a rooftop 600 feet away unless specifically watching for it. This vulnerability – a lack of 3D security coverage – was the central tactical failure that allowed a lone gunman to carry out the assassination with a single well-placed shot.

The security oversights become clearer when we contrast them with established protective doctrine of agencies like the U.S. Secret Service or Canada’s RCMP Protective Policing. The Secret Service layers its security with the concept of “concentric circles” or rings of protection – not only screening the immediate crowd and guarding the principal up close, but also extending vigilance to the surrounding environment (buildings, high ground, airspace). For major outdoor events, it’s routine for Secret Service to coordinate rooftop surveillance and even to position counter-sniper teams on neighboring buildings as a deterrent and quick reaction force. In the July 2024 attempted assassination of former President Trump in Pennsylvania, for example, four counter-sniper teams were on site, positioned on roofs behind the stage. Despite that, a shooter still managed to climb onto a shed outside the security perimeter and fire at the stage – but tellingly, he was neutralized within seconds by a Secret Service sniper’s return fire. The Trump case highlights two points: first, even with advanced countermeasures, elevated threats remain a serious challenge; second, without those measures, the outcome could have been far worse (in Trump’s case, one bystander was killed and Trump was only grazed, because security responded immediately from their own overwatch positions). In Charlie Kirk’s scenario, there were no counter-snipers, no rooftop observers, and no quick way to return fire at the attacker’s location. Local police units rarely have dedicated sniper teams at public events unless a specific threat is known. The RCMP’s Protective Policing branch (which safeguards Canadian officials) does emphasize intelligence-led protection and has some sniper capability via its Emergency Response Teams, but those resources are prioritized for top officials like the Prime Minister. An activist’s campus talk would not normally warrant an RCMP detail at all, and likely relied on campus security plans that focused on crowd management over long-distance threats. In short, the event’s security fell far below the level of a presidential or prime ministerial visit, and it showed in the single-point failure of not addressing vantage points. A Secret Service or RCMP advance team almost certainly would have flagged the surrounding rooftops as high-risk and demanded control over them, either by manning them or choosing a different venue. The absence of any such protocol here allowed the adversary to choose the time and place of attack with a huge tactical advantage.

Another factor was the lack of any physical protective infrastructure around Kirk. High-profile leaders sometimes speak behind bullet-resistant lecterns or deploy transparent ballistic shields in front of podiums during outdoor events. For instance, U.S. presidents at large outdoor inaugurations or rallies have in some cases used pop-up ballistic glass shields and always wear body armor under their suits. Nothing of that sort was present for Kirk – he was in casual attire, no body armor, sitting in an open-sided tent. His security detail did not (and realistically could not) shield him from a sniper round coming in without warning; their role would be more to cover him from an assailant rushing the stage. This again reflects the “security vs. optics” trade-off: employing visible heavy security measures (like armored enclosures or intense screening) at a college speaking event would have been seen as overkill and contrary to the informal, accessible vibe that Kirk likely wanted. Sadly, the shooter took full advantage of this deliberate light touch approach. The venue’s uncontrolled design and the decision not to harden the setup were institutional choices that left Kirk highly exposed. In summary, the protective environment for Kirk was characterized by low security density, no specialized counter-sniper overwatch, and an environment rife with elevated sightlines – essentially a perfect storm that a motivated attacker could exploit with relative ease.

The risk of sniper-style or elevated-position assassinations is not new – in fact, some of the most infamous assassinations in history were perpetrated from above. A classic example is President John F. Kennedy’s 1963 assassination in Dallas, where the shooter (Lee Harvey Oswald) fired from the sixth-floor window of a book depository building overlooking the motorcade route. The high perch provided concealment and distance, and the motorcade’s route past the tall building proved fatal when security was unable to cover that angle. Similarly, civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968 by a sniper (James Earl Ray) who took aim from a boarding house bathroom window across from King’s hotel balcony – another case where line-of-sight from a building was the decisive factor. Those 1960s incidents alerted U.S. security services to the danger of unguarded vantage points, prompting major changes in VIP protection (such as not using open convertibles and thoroughly scouting buildings along parade routes). However, the pattern has recurred internationally in more recent times as well. In the July 2022 assassination of Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, the scenario was different (the shooter approached from behind in a crowd, not from a height) but the after-action findings sound familiar: officials cited “a series of security lapses” and the lack of 360-degree surveillance that allowed the assailant to get in position unchecked. Abe’s bodyguards failed to watch the shooter’s approach from an angle behind Abe, analogous in some sense to failing to watch a rooftop – both are blind spots. Multiple security experts reviewing that case noted there were no concentric rings or vigilant observation of all directions, which is why the attacker got within meters to shoot. The through-line between the Abe case and Kirk’s case is an apparent complacency or blind spot in coverage: for Abe, it was the rear quadrant; for Kirk, the upward quadrant. In both cases, a single attacker exploited the gap.

Beyond historical cases, we have seen recent attempted assassinations in Western countries where overlooking sniper positions were not fully secured. The July 2024 attempt on former President Donald Trump in Butler, Pennsylvania is a striking example that parallels Kirk’s incident. In that case, a 20-year-old gunman armed with an AR-style rifle managed to climb onto a low warehouse roof about 400 feet from Trump’s rally stage. This location was actually just outside the official Secret Service security perimeter for the event. The shooter was partially concealed by the roof’s slope and some trees, meaning even four Secret Service sniper teams on site didn’t spot him immediately. Attendees in the crowd actually saw the suspicious figure on the roof and tried to alert authorities minutes before the shooting, but miscommunications delayed the response. The gunman opened fire from his perch, getting off eight shots – underscoring how deadly a vantage point can be when not neutralized in time. One bullet grazed Trump’s ear and others struck spectators (killing one), before a Secret Service counter-sniper finally shot the attacker dead about 16 seconds into the incident. That 2024 near-miss prompted intensive reviews of how the shooter got into position. Investigations found that a shortage of personnel left that particular roof unguarded – a detail chillingly reminiscent of Kirk’s case, except Kirk’s event had no sniper teams at all. In fact, a DHS Inspector General report later revealed the Secret Service was facing a 73% shortfall in trained counter-snipers relative to its requirements, meaning resource strains have been affecting coverage. A CBS News forensic mapping of the Trump rally incident showed the gunman’s shed roof position was about 410 feet away and partially obscured – effectively exploiting the boundary of the protective bubble. This is eerily similar to how the Kirk shooter appears to have operated at the edge of the event’s awareness.

Other incidents underscore that high-ground threats are an evolving challenge. In law enforcement, one recalls the July 2016 Dallas police ambush, where a shooter (positioned in a parking garage overlooking a protest route) sniped at officers, killing five – not an assassination of a single VIP, but a case where vantage point neglect had deadly results for police who weren’t anticipating a high-angle attack in that context. The 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting is another extreme example: the perpetrator brought an arsenal to a 32nd-floor hotel room and fired down into a concert crowd, killing 58. While not targeting a specific VIP, this massacre demonstrated how an elevated sniper’s nest can vastly increase casualties and delay police intervention. Investigations noted the shooter deliberately chose a high floor suite “because it overlooked the outdoor concert venue”, giving him an unobstructed view of 22,000 people. The Las Vegas after-action reports highlight that his “elevated position… increased his effectiveness and limited law enforcement’s ability to interfere” – a dynamic that equally applies to an assassin picking off a VIP: from high up and far away, the shooter can be gone (or hidden) before responders even pinpoint the origin of shots.

In Kirk’s case, by the time anyone figured out where the shot came from (minutes later via CCTV), the perpetrator had ample time to escape. This mirrors the JFK assassination, where Oswald had fled the sniper perch by the time officers searched the building. It also mirrors an often-forgotten 2002 incident in France: during Bastille Day, an extremist fired a rifle at President Jacques Chirac from within a crowd, about 100 meters away (not elevated but distant); he missed, but again it showed the danger of standoff attacks.

In parts of the world with persistently high assassination risks – say certain Middle Eastern or Latin American countries – protective units have adapted by being extremely aggressive in mitigating vantage threats. For example, when U.S. officials or military commanders operated in Iraq or Afghanistan, standard procedure was to secure rooftops along travel routes and event sites, often with allied sniper teams or overwatch from helicopters/drones. It was understood that insurgent snipers or RPG teams could use any building as a firing point, so responses ranged from posting counter-snipers on key rooftops to even controlling entire blocks of high ground. Israeli security for public figures is another case: after Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated in 1995 (though by a ground-level shooter), Israeli Shin Bet protocols for open events became very strict, sometimes employing bullet-resistant barriers and intensive monitoring of buildings. In many Latin American countries where kidnapping or assassination is a threat, VIPs travel in armored convoys with escort vehicles scanning rooftops, and public speeches are rare or heavily guarded. The trade-off, of course, is that these measures create a fortress-like atmosphere. Notably, Japan – which traditionally had a low-threat environment – had to overhaul its VIP security after Abe’s assassination, suddenly adopting measures more akin to high-risk countries. They introduced more rigorous advance inspections and increased the number of police deployed to guard all angles (indeed, Japan’s National Police chief publicly took responsibility and resigned, acknowledging the need for a “fresh start” in protective tactics). The point is, where threats are perceived to be high, protective doctrine explicitly plans for snipers. This can include using spotter teams with high-powered optics, designating counter-snipers in vantage points before any event, employing jamming or drone surveillance to spot unusual movements, and sometimes even altering venues last-minute if an uncontrollable vantage point is discovered. North American VIP events historically haven’t had to be as militarized, except for the President and similarly high-risk figures, but the attack on Kirk and others suggest this might be changing.

It appears there may be a doctrinal gap or emphasis imbalance in many protection plans: close-range threats (like a person with a knife or handgun rushing the stage) have typically garnered the most attention. This is understandable – since the 1980s, many assassination attempts (Reagan 1981, Pope John Paul II 1981, etc.) were up-close encounters, leading to doctrines of strong inner perimeters, metal detectors, and immediate bodily protection (the classic image of agents forming a human shield). However, long-range rifle threats were relatively rare in recent decades, perhaps leading to some complacency. The successful long-distance hit on Kirk starkly demonstrates that a determined adversary can bypass the traditional security rings entirely by attacking from outside their radius. Modern protective manuals do address sniper threats – for instance, the U.S. Secret Service Counter Sniper Team exists precisely for this scenario – but outside of high-level protectees, these measures often aren’t implemented. There’s evidence that protocols haven’t been uniformly updated to treat any prominent public event as a potential sniper target. Even in the Trump 2024 attempt, the fact that the gunman was able to get into position undetected suggests procedural shortcomings (or lack of resources to fully execute procedure). A congressional task force reviewing that incident noted surprise at how the assailant could fire multiple shots – meaning something failed in either intelligence (not anticipating the method) or execution (insufficient coverage). Similarly, the witnesses of Kirk’s shooting expressed shock at the lack of venue security – “I was in total shock,” said one student, emphasizing how “security was lacking” and easy to bypass at the event.

It’s fair to say protective doctrine has traditionally prioritized threats on the ground and among the crowd (where most past attackers emerged), potentially underestimating how the rise in political violence might encourage “standoff attacks”. In the current era, high-velocity rifles with effective optics are widely available, and assailants may prefer a sniper-style attack as it increases their chance of escape and success. If protective doctrine does not evolve to treat every vantage point as a potential sniper nest, more incidents like this could occur. We might be witnessing a broader trend where public figures are now targeted from afar, not just by the deranged person rushing the stage. That demands a culture shift in security planning: scanning rooftops and windows might need to become as routine as patting down the front-row attendees. The Kirk assassination could join the Trump attempt and Abe assassination as catalysts for re-examining training and procedures to close those gaps. Protective units will likely update their risk assessments to weigh elevated threats on par with close-quarter threats, ensuring that going forward, event sites are chosen and secured with a sniper’s-eye-view in mind.

The evidence suggests that Kirk’s assassination was not a mere one-off lapse by a single negligent officer, but rather a symptom of systemic shortcomings in VIP protection amid a changing threat landscape. Firstly, multiple incidents over the last few years – across different jurisdictions – indicate a pattern of inadequate coverage of elevated angles (the attempted shootings of Trump, the successful hit on Kirk, the attack on Japan’s Abe from behind, etc.). This points to a broader failure to institutionalize lessons about 360-degree and vertical security. In Kirk’s case, certainly there were some specific planning failures (e.g. the event organizers or security detail did not account for rooftops at all), but this happened under a general assumption that such an event wasn’t “high risk” enough to warrant extreme measures. That assumption itself is outdated given the current environment. It reflects a possible institutional inertia – security practices that haven’t caught up to the reality of intensifying political violence. Utah authorities likely treated Kirk’s visit as a routine speaking engagement requiring basic police presence. In hindsight, that was a miscalculation of threat level, but it’s an institutional one that many would have made prior to this wake-up call. The fact that multiple high-profile attacks occurred in 2024–2025 (Trump, Minnesota lawmaker, Kirk, etc.) suggests a broader trend. Analysts note that political violence in the U.S. has been escalating into a “feature” of public life rather than isolated aberrations. Judges, lawmakers, and public figures across the spectrum have reported spikes in threats and harassment, and tragically some have been attacked or killed. In June 2025, for example, a man impersonating a police officer assassinated a Minnesota state legislator (and her husband) at their home, and wounded another lawmaker – a case of targeted political murder that underscored the pervasiveness of the danger. This context strongly indicates that Kirk’s assassination was part of a larger pattern of attackers feeling emboldened to use violence for political ends. Security lapses certainly enabled each incident, but the common thread is a failure of imagination or preparedness at an institutional level to anticipate these deadly scenarios.

A recurring theme in recent security failures is under-resourcing of protection units and over-reliance on inadequate local measures. The U.S. Secret Service itself has been strained – as mentioned, a DHS OIG report in August 2025 found the Secret Service Counter Sniper Team was staffed at only 27% of its required size, a “dire” shortage that “could limit the Secret Service’s ability to properly protect our nation’s most senior leaders.” In 2024, Secret Service snipers had to log tens of thousands of overtime hours to cover events, and even then gaps were evident. If the elite agency guarding the President is stretched thin, one can imagine the situation for lesser-protected figures. Charlie Kirk, being a prominent presidential ally but not an elected official, fell into a gray zone where security was essentially left to an ad-hoc arrangement. His organization likely hired some private security for personal protection, and the university provided some officers for public safety, but no dedicated unit exists in the U.S. to comprehensively protect such individuals. In Canada, the RCMP only protects those designated (like cabinet ministers or judges) – a private citizen activist, no matter how well-known, wouldn’t have a state security detail. This raises the issue: as threats broaden, should the umbrella of official protection be widened? Or should events with certain risk profiles automatically trigger more robust policing resources? Currently, it appears resource allocation has not caught up – there are simply not enough trained protective agents or officers to cover all the venues and people now under threat. In Kirk’s case, six local officers for 3,000 people in an open campus with multiple buildings was clearly insufficient (witnesses described it as “too few [officers]… if someone wanted to do something, they could,” not realizing how prophetic that was). One could characterize this as systemic under-allocation of protection to “soft” VIP targets, either due to budget constraints or because protocols didn’t mandate more. Additionally, there may have been over-reliance on the campus/local police without supplementing with specialized units. Campus police are not typically equipped to deploy counter-snipers or armored teams; they handle routine security and maybe crowd control. Expecting them to secure against a trained marksman is a stretch without additional support. In an era of heightened political tensions, this division of responsibility – where only the President or top officials get the A-team security, and others are left with very basic measures – might need rethinking.

Encouragingly, some governments are recognizing the need to boost resources. In Canada, for example, funding for the RCMP Protective Policing program is being increased to address evolving threats to public figures. The RCMP sought an additional C$26 million for 2024-25 specifically to hire more Close Protection Officers, improve threat intelligence, and bolster training and protective operations centers. This was explicitly justified by the fact that “the threat and security environment for Parliamentarians has continued to evolve,” with officials “increasingly subject to a broad range of threats.” In the U.S., Congress and DHS are likewise scrutinizing Secret Service and other agencies’ preparedness after the recent incidents. These measures acknowledge that current protective postures might be underpowered for the new reality. Without such enhancements, agencies risk being perpetually reactive, investigating assassinations after the fact rather than preventing them.

One intangible yet critical factor is the political reluctance to visibly “militarize” protective security at public events, due to concerns over optics and values. Democracies pride themselves on leaders being accessible to the people – a heavily fortified event with rooftop snipers, sniper nests, metal detectors, and everyone kept at arm’s length can send a message of fear or elitism. Politicians and organizations often resist excessive security because it can dampen the atmosphere and deter attendance. In the case of Kirk’s campus visit, it’s plausible that neither Turning Point USA nor the university administration wanted airport-style security screening or a phalanx of SWAT on rooftops. It would be incongruent with an event meant to showcase open dialogue. Governor Spencer Cox of Utah hinted at this tension even as he decried the assassination – he emphasized the importance of campuses as places for free debate and lamented that this attack threatens that openness. There may also be an element of complacency bias – an assumption that “it can’t happen here,” especially in a peaceful setting like a university in Utah. That bias was shattered on September 10th. Going forward, there will be debates about how much to harden such events. Politically, ramping up visible security might conflict with leaders’ desire to appear unafraid and among the people. For instance, after Shinzo Abe’s assassination, Japanese politicians were faced with altering a long tradition of minimal security at close-range campaign stops – something they had cherished as a sign of trust in society. Similarly, U.S. campaign events have historically been quite accessible (at least for non-president candidates) to allow retail politics. If every rally now must have snipers on buildings and bag searches, it changes the nature of campaigning. Yet, the alternative risk is too high to ignore. We may see a begrudging shift wherein even mid-level political events get a heavier security footprint. Already, campaign rallies for the 2024 U.S. election were under unprecedented Secret Service protection due to the attempt on Trump and a general spike in threats. There is evidence of an attitudinal shift: OSINT observers and security experts are increasingly calling out the need to prioritize safety over optics. The online OSINT community that followed the Kirk shooting, for example, has been highlighting how easily this attack succeeded and arguing that open-air events need rethinking. Some commentators note that while a “free and open” event is ideal, the reality of armed political extremism means better safe than sorry – visibility can be slightly reduced (through subtle measures like undercover agents or surveillance drones) in order to thwart would-be attackers. Of course, others worry that overreacting could itself chill free speech (turning campuses into armed camps or deterring controversial speakers for fear of violence). It’s a delicate balance that protective doctrine must navigate.

Within the open-source intelligence and security analysis community, there appears to be a consensus that political violence has entered a dangerous new phase, requiring adaptation. Analysts point to the growing list of incidents as evidence that this is not partisan or isolated – extremists of various stripes have resorted to violence (the Guardian analysis notes events “across all parts of the ideological spectrum”) and thus any public figure could be a target now. The OSINT community emphasizes that we are in, as Professor Robert Pape put it, an “era of violent populism” where a troubling percentage of the public – on both left and right – have become accepting of using force to achieve political aims. This creates a volatile backdrop for VIP protection. The consensus is that security protocols must adapt swiftly: more intelligence-sharing about threats, better screening of open-source chatter for clues, and a no-blind-spot approach to event security. At the same time, OSINT observers caution about the risk of a “security bubble” that cuts leaders off from citizens, noting that part of the attacker’s goal can be to instill fear and disrupt democratic discourse. The ideal balance, as framed by experts, is to harden targets enough to deter or defeat attackers, but not so much as to completely close off the public square. After Kirk’s death, even voices typically critical of heavy security acknowledged that some recalibration is needed – for instance, commentators noted that if a college campus in a quiet city can host a political murder from a rooftop, every public event venue should be assessed with that possibility in mind. A common refrain in OSINT forums after the shooting was “How was there no one on that roof?”, reflecting disbelief at the lapse and a call to never let it happen again. In sum, the consensus is forming that this assassination is part of a broader trend of political violence meeting soft targets, and it underscores the need for systemic changes in protective doctrine, resource allocation, and the cultural acceptance of necessary security measures to safeguard democratic participation.

The assassination of Charlie Kirk exemplifies a paradigm shift in VIP threat environments – one that demands both tactical and policy-level responses. What might once have been dismissed as an isolated tragedy appears instead to be emblematic of broader failures in how we protect public figures in open venues. The evidence reviewed suggests a confluence of tactical lapses (failure to secure vantage points, insufficient on-site security), operational shortfalls (inadequate planning and threat assessment), and institutional gaps (outdated doctrines and under-resourced protective units). Rather than an isolated fluke, Kirk’s killing fits a pattern of escalating political violence exploiting security blind spots. To prevent this from becoming the “new normal,” a series of changes should be considered:

In conclusion, the killing of Charlie Kirk is a tragedy that has laid bare tactical failures and systemic issues in VIP security. A single elevated gunman was able to defeat an inadequate protective setup – a scenario reminiscent of dark moments in history but now resurfacing in the present day. The question posed was whether this reflects an isolated lapse, systemic negligence, or a broader trend. The weight of evidence leans toward it being a manifestation of a broader trend and systemic gaps: multiple recent cases show the same vulnerabilities, and the protective system as a whole has not fully adjusted to the current threat matrix. However, this assessment also offers a roadmap to remedy those failings. With comprehensive adjustments – from tactical deployments at events to policy-level resource boosts – VIP protective security can rise to meet the challenge. The balance between openness and security will always be delicate, but recent events argue that the pendulum must swing at least somewhat toward greater security coverage to avoid open societies becoming shooting galleries. Ultimately, the goal is to ensure that leaders and influencers can engage with the public without turning into easy targets, preserving both safety and the democratic spirit of accessibility. The death of Charlie Kirk is a sobering reminder of what happens when that balance falters – and a rallying cry to never let such an avoidable breach happen again. Now that it has been confirmed that Charlie Kirk’s assassin, Tyler Robinson, had a trans roommate, who may also have been his lover, the puzzle before investigators becomes even more complex.

[…] first shot missed and the second proved fatal. By contrast, a one-shot, one-kill scenario like the Charlie Kirk shooting is highly atypical, with few modern precedents outside of military-style sniper […]

Thank you for your detailed and very important look at the dramatic change in what is necessary for high profile security. My first thought was a 50.00 drone could have spotted this guy on the roof and why didn’t one of the 6 Kirk sec guys be assigned to a simple drone. ? No trees. Clear day. A venue literally surrounded by buildings. After Butler I would think a drone would be at minimum a basic for overhead view. The shooter not only got on roof of one building but crossed to another before taking his position. How did nobody even with decent binoculars see this ? When people are killed in airplane accidents or drunk driver that is force majeur. At first I thought the assassin shot from a window of a building which would have been harder to prevent. But the ROOF? I am sickened by the loss of life of a 31 year old father who was not even an elected politician whose entire platform was INVITING people with dissenting beliefs to dialogue. And respectfully he did that. I do not know why any political figure would ever speak at an open air event ever again. And that will be Americas loss of that as you said casual vibe sort of like Socrates speaking at the town square —just come and engage. We are all a poorer country for this appalling horrific public execution of a young man for his desire to debate.

[…] history. Now, as a follow-up, we turn to the recovered Mauser .30-06 bolt-action rifle from the Charlie Kirk assassination. This piece examines what that weapon choice reveals about the shooter’s capabilities and intent, […]

[…] Felony Discharge of a Firearm Causing Serious Bodily Injury (First‑Degree Felony): the shooting of Charlie Kirk, engaged in from a high vantage point, endangered other people in the b… […]

[…] player, Antonio Brown, amplified a tweet alleging that “the Jew that was used as a decoy in the Charlie Kirk assassination was also used for 9/11 propaganda,” which provoked condemnation for antisemitism and baseless […]

[…] such violence “ends now”. Trump himself blamed “the radical left” for the shooting, earlier likening Kirk’s death to leftist terrorism. In line with this, Reuters observed, many Trump supporters blamed the political left and sought […]

[…] Background: Charlie Kirk’s Assassination […]

[…] Charlie Kirk Assassination as a […]

[…] areas of ironclad unity in the conservative movement. That consensus is now visibly collapsing, and Kirk’s assassination — and Carlson’s framing of it — have become flashpoints in that […]

[…] strikes. • Component Dispersal: Critical systems are distributed to reduce vulnerability to single-point failures like snipers at elevation. • Redundant Systems: Multiple backup systems ensure continued operation despite successful […]