Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

The Falcon 50 disappeared from Turkish radar at 20:52 local time, December 23, 2025. Electrical failure, they said – arguably the most convenient of technical malfunctions – the kind that erases generals and their delegations with the efficiency of a delete key. General Mohammed Ali Ahmed al-Haddad, Libya’s chief of general staff, along with four senior officers and three crew, became additional data points in the actuarial tables of violent North African politics. The wreckage scattered across Haymana district, 75 kilometers south of Ankara, still smoldering when Turkish gendarmerie found it two kilometers south of Kesikkavak village.

The timing carries that peculiar weight that makes intelligence analysts reach for their second cup of coffee and start pulling files – wondering if they should take up smoking again. Al-Haddad had spent the day in meetings with Turkish Defense Minister Yasar Guler and Chief of General Staff Selcuk Bayraktaroglu—high-level talks about military cooperation, the kind where actual decisions get made rather than the usual diplomatic theater. Turkey’s parliament had just extended the mandate for Turkish troops in Libya another two years. The general was flying home with his ground forces commander, his military manufacturing chief, his senior adviser, and a military photographer. All the people you’d bring to serious conversations about hardware and strategy.

Plane crashes happen. Falcon 50s, while generally reliable, have accumulated their share of incidents over decades of operation. Electrical systems fail. Pilots make errors. Weather intervenes. The Turkish officials were quick to rule out sabotage in their initial assessment, which is either reassuring or exactly what you’d say while the real investigation proceeds behind closed doors.

But Libya doesn’t do coincidence well. It does conspiracy, faction, betrayal, and the grinding logic of tribal politics wrapped in the language of state institutions. Al-Haddad represented one of the last figures trying to maintain some fiction of a unified Libyan military while navigating the impossible geometry of Misrata’s power brokers, Turkish patronage, the ongoing threat from Haftar’s forces in the east, and the general chaos that has defined Libya since 2011.

Mohammed Ali Ahmed al-Haddad was born in Misrata in 1967, graduated from military college in 1987, and spent the next 24 years as a career officer under Gaddafi before making the calculation that matters most in revolutionary moments—which side survives. In February 2011, he was among the first Misratan officers to defect, joining the uprising that would eventually drag Libya into its current state of perpetual almost-war.

Post-revolution, he commanded the Halbus Brigade, one of Misrata’s many militias that emerged from the wreckage of the old state apparatus. Misrata—Libya’s third city, industrial powerhouse, crucial port—generated some 56 brigades during the chaos. The Halbus Brigade was significant enough that when the Government of National Accord (GNA) started trying to formalize command structures, al-Haddad got the Central Military Region in June 2017. In August 2018, he supervised ceasefire arrangements in Tripoli when western Libyan militias decided to shoot at each other instead of their putative enemies. In September 2018, he was kidnapped at the end of a military meeting and later found alive in Karzaz—a reminder that in Libya, even high-ranking officers aren’t immune to the fundamental instability of the whole project.

By August 2020, he’d climbed to chief of general staff for the GNA’s successor, the Government of National Unity (GNU). The position makes you responsible for pretending Libya has a unified military while actually managing a confederation of militias, regional power brokers, and foreign patrons with competing interests. It’s the kind of job that ages you fast or gets you killed.

Al-Haddad was described as someone who “went by the book,” which in the Libyan context means he tried to maintain some professional military standards while swimming in a sea of militia politics and personal loyalty networks. He didn’t take sides with specific militias “no matter how powerful they were,” according to Al Jazeera’s Malik Traina, who knew him personally. That kind of neutrality makes you valuable for maintaining coalitions. It also makes you a potential problem for anyone who wants to consolidate power – when Canadian, American and other Special Operations forces operate in the country with near impunity – and no meaningful public recor

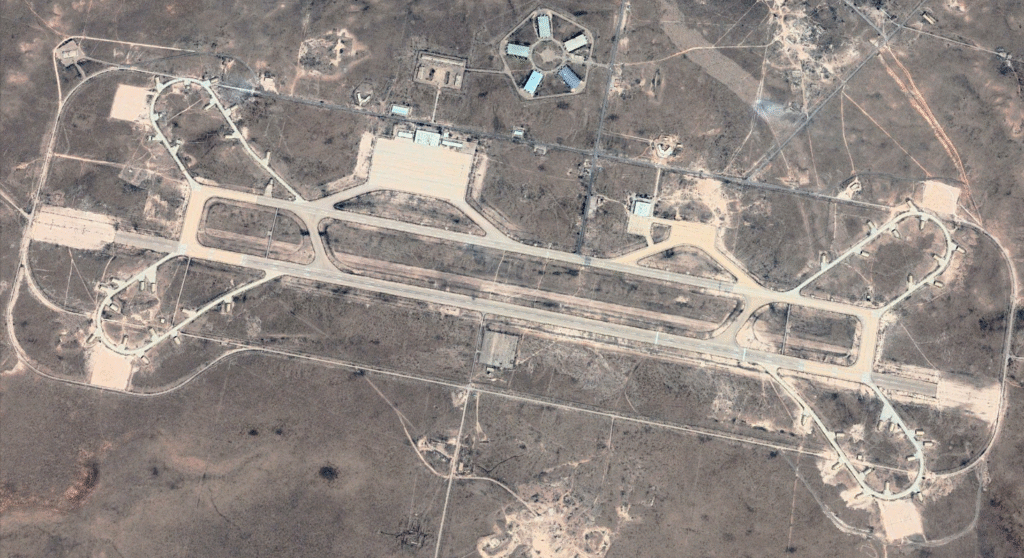

But here’s where it gets interesting, in that particular way that makes archival researchers sit up and start pulling thread: Al-Watiya Air Base, alternatively known as Al-Wattiya or Al-Watyah, 140 kilometers southwest of Tripoli, 27 kilometers from the Tunisian border, one of the largest military airfields in Africa. Built by the Americans during World War II when North Africa was worth dying over for different reasons than today’s resource wars and migration routes. Expanded by Gaddafi during Libya’s oil boom, designed to project power across the Sahel and Mediterranean. Forty-five hardened aircraft shelters, infrastructure to support 7,000 personnel, strategic location at the intersection of multiple conflict axes.

The base has changed hands more times than a marked deck in a poker game. Originally under Libya Dawn control after 2014, it was captured by Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) on August 9, 2014, early in the second civil war. The LNA held it for nearly six years, using it as a forward operating base for their campaigns in western Libya, a platform for air strikes against rivals, and a symbol of their claim to represent Libya’s legitimate military. It has now been extensively renovated by Turkiye, and is one of Erdogan’s most important airfields in the region.

Which brings us to December 2015—a period when Libya had achieved that special kind of chaos where multiple governments, dozens of militias, and various international actors were all pursuing incompatible objectives in the same small geographic space.

The situation around Wattiya in late 2015 was fractally complicated: zoom in at any level and you find the same patterns of competing factions, tactical fluidity, and the fog of war rendered literal by dust storms and information operations. The base itself was held by LNA forces loyal to Khalifa Haftar’s eastern government, but the surrounding territory was contested by Libya Dawn forces—primarily Misratan militias (including al-Haddad’s Halbus Brigade) operating out of Tripoli in coordination with what remained of the GNA’s predecessor administration.

A March 2015 report from Middle East Eye described the situation with admirable clarity: Libya Dawn forces had pushed to within 22 kilometers of Wattiya after months of fighting. The standoff had “a Mad Max edge,” with fighters using improvised armor and Soviet-era heavy weapons. Local families continued living on the fringes of the combat zone, trapped between competing forces, their allegiances divided. Libya Dawn held the advantage in fuel supplies—petroleum had become a weapon, with militias confiscating gas canisters from civilian cars to prevent them reaching Haftar’s forces in the mountains.

The commander of Libya Dawn’s El-Khoudorat El-Moujahida Brigade, Muftah Abuleafa, described Wattiya as “half-surrounded” in late 2014/early 2015. His forces could hit the facility with missiles, and they were “waiting for them to surrender, and negotiate with Misrata.” The LNA’s Colonel Idriss Madi, commanding operations in the western region, called the stalemate a “nightmare to Libya Dawn” that had “exhausted them.”

This wasn’t theoretical combat. This was grinding, resource-intensive warfare with artillery exchanges, armored vehicle movements, and the constant tactical problem of operating in terrain that favored defense. The Nafusa Mountains—the Jebel Nafusa region where Wattiya sits—is Berber country, complex tribal geography, elevations that make approaches visible from kilometers away. The Zintan brigades controlled much of the mountain region, their loyalties shifting based on tactical calculations and long-standing feuds that predated Gaddafi.

By December 2015, the situation had settled into a siege pattern. Wattiya remained in LNA hands, but isolated, dependent on supply lines running through Zintan and points east. Libya Dawn controlled Tripoli and the western coastal cities. The nascent GNA—created through the UN-brokered Skhirat Agreement signed literally that month, December 2015—existed more on paper than in practice. Multiple militias claimed to represent the legitimate Libyan government. ISIS controlled Sirte and was expanding. The country had fractured into zones of control that bore only passing resemblance to any constitutional framework.

Into this environment came external actors pursuing their own agendas. The UAE was already backing Haftar with arms and air support. Qatar was supporting Islamist-aligned militias. Egypt was providing logistics and political cover for the LNA. Turkey was beginning the involvement that would eventually see them deploy forces and military advisers. Western powers—particularly France, UK, and the United States—were conducting counter-terrorism operations, ostensibly targeting ISIS but inevitably entangled with the broader factional conflict.

Which brings us to an interesting data point that’s been sitting in public view since 2015, the kind of thing that makes you wonder about operational security in the age of Facebook. In mid-December 2015, the Libyan Air Force—or an entity claiming to be the Libyan Air Force, because there were at least two competing air forces at this point—posted photographs to social media showing U.S. special operations aircraft at Wattiya airbase. A C-146A Wolfhound, specifically, with visible tail numbers. Approximately 20 operators visible in the frame, faces clear enough for identification if you had the databases and motivation.

The 919th Special Operations Wing operates C-146A Wolfhounds out of Eglin Air Force Base—small fleet, only about 20 aircraft total, used for low-visibility insertion and extraction of special operations forces. The presence of this particular asset at this particular location during this particular timeframe raises questions that nobody with operational knowledge has been particularly eager to answer publicly for the past decade.

A few outlets reported it at the time—brief mentions that U.S. special operations forces had been photographed in Libya, followed by the usual non-denial denials from official spokespeople and then… silence. The story died. The photos remained public but uncommented-upon. The kind of thing that goes into the folder marked “interesting but unexplained” and sits there until someone with specific knowledge decides to illuminate it or until enough time passes that operational security concerns fade and the story can be told.

The timing matters. December 2015 was a period when the Obama administration was conducting operations against ISIS in Libya but maintaining the public position that the U.S. had “no boots on ground” in any combat role. Special operations forces were nominally conducting training, liaison, and intelligence collection—activities that exist in that useful gray zone where the definition of “combat” becomes extremely flexible.

But Wattiya wasn’t ISIS territory. It was LNA-controlled, part of Haftar’s network. If U.S. special operations forces were there, they were coordinating with Haftar’s people—the anti-Islamist faction backed by Egypt and the UAE, the force that would eventually launch the 2019 assault on Tripoli. This was months before the GNA would become the official UN-recognized government. The political geometry was still in flux.

The operational question is straightforward: What were they doing there? The answers range from benign (liaison, coordination, intelligence sharing about ISIS) to problematic (direct support for Haftar’s operations, which would contradict stated U.S. policy supporting a unified government) to deeply complicated (some operation that went sideways, requiring recovery or negotiation, the kind of thing that gets classified for decades).

Al-Haddad, commanding Misrata forces trying to take Wattiya during this period, would have had intelligence on U.S. presence there. His forces were close enough to observe aircraft movements, close enough to have informants, close enough to know when something unusual was happening. The Libyan Air Force posting photos suggests someone wanted the presence documented—either as evidence of cooperation or as leverage for future negotiations.

Fast-forward to 2025, and Libya remains divided despite the nominal unity government. Al-Haddad has spent five years trying to consolidate what passes for a Libyan military while managing Turkey’s growing influence. Turkey deployed forces to Libya in 2020, provided the Bayraktar TB2 drones that turned the tide against Haftar’s 2019 Tripoli offensive, restructured GNA forces into something resembling a coherent fighting force, and established a military presence that continues today.

The meetings in Ankara on December 23, 2025, were about extending that presence—another two years of Turkish troops, more military cooperation, deeper integration of Turkish training and equipment into Libya’s force structure. This makes Turkey the dominant external power in western Libya, displacing or subordinating the various Gulf states and European powers that had previously competed for influence.

Al-Haddad was central to this arrangement. He knew where the bodies were buried, figuratively and sometimes literally. He’d been a Misratan militia commander when Misrata was the crucial swing power in western Libya. He’d navigated the impossible politics of trying to unify forces that fundamentally didn’t want to be unified. He’d survived kidnapping, factional conflict, and the general tendency of Libyan military officers to end up dead or in exile.

And he knew what happened at Wattiya in December 2015, because his forces were there, watching, collecting intelligence on who came and went and what they did.

Plane crashes are convenient. They destroy evidence. They create confusion about cause. They can be plausibly denied as accident while sending a clear message to anyone who understands the context. Turkish officials ruling out sabotage in the initial hours doesn’t mean much—that’s standard procedure while the real investigation proceeds. The causes of aircraft incidents are usually over-determined: multiple small failures cascading into catastrophe, or a single catastrophic failure that could have been anything from maintenance to intentional sabotage.

The question isn’t whether it’s possible this was just an accident. Of course it’s possible. Falcon 50s have crashed before. Electrical systems fail. The weather over central Turkey in December can be challenging. These things happen.

The question is whether the timing and context make this worth paying attention to, and the answer is yes. Al-Haddad dies days after high-level military talks with Turkey, hours into his flight home, taking with him his ground forces commander and his military manufacturing chief—the exact people you’d need to eliminate if you wanted to disrupt Libyan military continuity and Turkish influence simultaneously.

Who benefits? The list is long: Haftar’s forces in the east, still seeking to dominate Libya; Gulf states concerned about Turkish regional influence; various Libyan factions that prefer chaos to any form of centralized authority; international actors who want Libya to remain weak and divided. The country is a geographic chokepoint for Mediterranean migration, sits atop significant oil reserves, and represents a persistent source of instability that can be exploited or contained depending on policy objectives.

But the connection to Wattiya—to that December 2015 moment when U.S. special operations forces were photographed at a Libyan airbase during a period of official “no boots on ground”—creates a different kind of question. Al-Haddad would have been among a very small number of people who could provide detailed intelligence about what actually happened there. He was in position, he was on the opposing side, he had every motivation to collect and preserve information about U.S. operations on enemy territory.

If that operation involved anything beyond routine liaison—if something went wrong, if personnel were compromised, if negotiations were conducted that shouldn’t be part of the official record—then al-Haddad’s knowledge becomes a different kind of asset or liability depending on your perspective.

The Turks would want to know. They’re now the dominant power in western Libya and would have a legitimate intelligence interest in understanding what the U.S. was doing there during the period when Libya was fragmenting. Other actors might have reasons to ensure certain information doesn’t surface, especially if it contradicts official narratives or reveals operations that were never properly authorized.

This is where the modern surveillance state creates interesting problems for operational security. Those Facebook photos from December 2015 are still out there, archived in multiple locations, now placed on the blockchain by Prime Rogue Inc, and have been analyzed by various intelligence services and independent researchers. Flight tracking data from that period exists in commercial databases. Satellite imagery is time-stamped and stored. Metadata persists.

Anyone with sufficient motivation and technical skill can reconstruct the basic facts: what aircraft were where, when they moved, what patterns emerge from the data. The specifics of what happened on the ground require human sources—people who were there, people who saw the reports, people who know what wasn’t supposed to be disclosed.

Al-Haddad was one of those people. Now he’s not.

The official investigation will run its course. Turkey will determine the cause of the crash with whatever level of precision serves their interests. Libya will appoint a replacement chief of staff who will face the same impossible mandate of unifying forces that don’t want to be unified. The Turkish military presence will continue or expand. The various factions will continue their grinding competition for control and resources.

But the questions remain: What exactly happened at Wattiya in December 2015? Who was there? What operation required C-146A Wolfhounds and approximately 20 Delta Force operators at an LNA-controlled airbase during a period when the U.S. officially had minimal presence in Libya? What went wrong or right that made it worth documenting on social media? And who else knows the answers?

Al-Haddad’s death removes one source of potential answers. Whether that’s coincidence, consequence, or something more calculated remains to be determined. In the actuarial tables of North African politics, convenient deaths are common enough to pattern-match against historical precedent but rare enough to warrant attention when they occur.

The archive persists. The photos remain. The questions accumulate. And somewhere, in classified files and unexamined testimony, the actual answers wait for someone with access and motivation to pull the thread.

This article is just the beginning of Prime Rogue Inc’s investigation of Al-Wattiya air base in Libya. In fact, and based on a combination of HUMINT and OSINT, Prime Rogue Inc President Kevin Duska is currently engaged in a project, tentatively entitled Decoding Delta Force. More details are to come but this article represents entry 0.1 in the Decoding Delta Force Series found on the Decoding Delta Force Website, and on the Decoding Delta Force Substack. You can support this investigation, and get insider updates, via the Decoding Delta Force Patreon