Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

As the 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis approaches, the UK is deploying a sophisticated, multilayered protection and intelligence posture to safeguard the Prime Minister and British delegation. Behind the public diplomacy and polished photo ops lies an intricate network of close protection teams, intelligence liaisons, air logistics, motorcade planning, and legal arrangements for armed operatives operating abroad. This report maps the British security footprint in Canada for the summit — from RAF aircraft and armored convoys to MI5-MI6 liaison with Canadian agencies and OSINT breadcrumbs left in the open. Drawing on precedent, leaked deployments, and tactical doctrine, we detail how SO1, MI5, and GCHQ integrate with host-nation security to protect the UK’s leadership at one of the highest-profile events of the year.

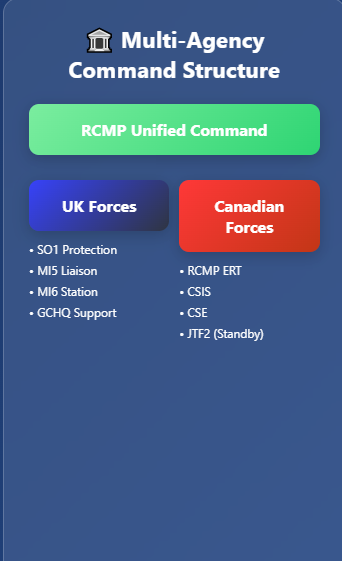

When operating overseas, SO1 officers liaise closely with host-country security. For example, in Canada they would coordinate with the RCMP’s protective policing unit to integrate motorcade movements, venue security, and local threat updates. The host nation usually handles the outer perimeter and general venue security, while UK PPOs concentrate on immediate close protection of the principal. Historical incidents show UK officers do carry firearms abroad with host permission – notably, a Met SO1 bodyguard had a handgun negligent discharge at Israel’s Ben Gurion Airport during a PM visit, underscoring that British PPOs were armed and operating under host-nation oversight. MI5 (Security Service) supports the PM’s detail by providing threat assessments even overseas, working via liaison officers to share any intelligence on threats to the delegation.

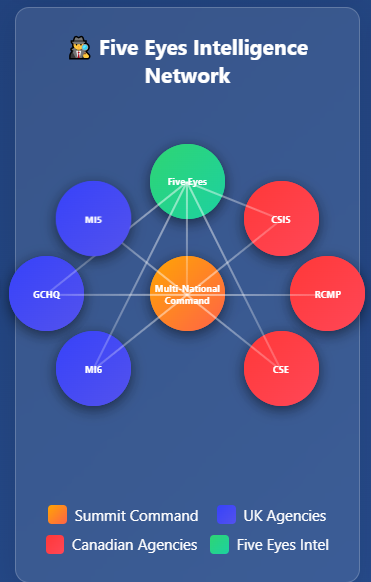

Significant UK intelligence resources are aligned with summit security. MI5, while a domestic security agency, maintains overseas liaison staff (Security Liaison Officers) in key allied countries; it’s common for an MI5 officer at the British High Commission to coordinate with Canadian intelligence on summit threats (a practice dating back decades). For the G7, MI5 would liaise with CSIS (Canadian Security Intelligence Service) and the RCMP’s Integrated National Security units to exchange information on any terror, espionage, or other threats to UK delegates. MI6 (the Secret Intelligence Service, or SIS) and GCHQ also plug into this effort via the Five Eyes partnership. The UK and Canada are part of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, which means British and Canadian agencies share intelligence in real time. It is likely that a MI6 station officer and perhaps GCHQ staff work with Canada’s Communications Security Establishment (CSE) during the summit to monitor external threat streams (e.g. signals intelligence on hostile actors). Historic precedent for such coordination is strong – during events like G7/G20 summits or NATO meetings, UK intelligence station personnel join host-country security task forces to ensure any clues of plots (from cyber threats to protest violence or terrorism) are rapidly communicated to both the Canadians and the UK delegation’s security team.

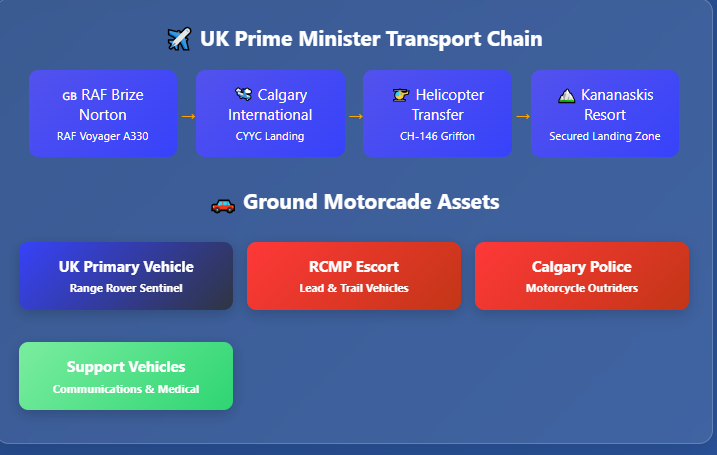

The UK Prime Minister is expected to arrive on an RAF Voyager aircraft, an Airbus A330 MRTT configured for VIP travel. This RAF Voyager is the UK’s dedicated VVIP transport and typically carries the PM, senior staff, close protection officers, and accompanying press. (The British government also has smaller VIP jets, but for a major summit with a delegation, the Voyager is used due to its range and capacity.) It would likely fly direct to Calgary International Airport, the nearest major airport to Kananaskis. From Calgary, leaders will transfer to helicopters for the final leg to the remote summit site – in the 2002 Kananaskis G8, for example, leaders landed in Calgary then arrived by helicopter to the mountain venue 65 miles away. A similar plan in 2025 would minimize exposure and travel time on the ground. If helicopters are used, Canada’s air force will provide transport (e.g. CH-146 Griffon helicopters) to ferry the PM and entourage to Kananaskis, where a landing zone near the resort is secured.

On the ground, the Prime Minister’s motorcade is a joint UK-Canadian effort. The centerpiece is the PM’s official armored car – historically the Jaguar XJ Sentinel, though recently armoured Range Rover Sentinel and Audi A8L models have been adopted. These vehicles, maintained by the UK Government Car Service, are often flown in or shipped ahead of time for high-security visits. Each is custom-built with extensive protection (reinforced armor, bulletproof glass, run-flat tires) and even CBRN air filtration for chemical attacks. The UK’s RaSP protection drivers operate the PM’s car, while the convoy is augmented by host-provided vehicles and police escorts. It’s likely the RCMP will provide marked or unmarked escort vehicles and motorcycle outriders once the motorcade is on Canadian soil, similar to how the Metropolitan Police’s Special Escort Group escorts dignitaries in London.

Vehicle logistics require advance planning: the UK may send its armored cars via RAF cargo aircraft (such as a C-17) to Canada, or alternatively, rely on a Canadian-provided armored vehicle if available (the Privy Council Office of Canada sometimes supplies armored SUVs for visiting leaders if needed). RCMP officials have noted that ahead of the G7 they began procuring essential vehicles and equipment for the summit – this likely includes fleets of SUVs, limousines, and possibly locally rented vehicles for delegations. The arrival motorcade for the UK PM would depart Calgary airport under heavy police escort by the Calgary Police and RCMP. If no helicopter transfer, the convoy would make the roughly 1.5-hour drive to Kananaskis with highway patrol clearing the route. Within the secured zone, British PPOs stay with the principal’s vehicle, while Canadian vehicles lead and trail for route security. Motorcade movements are tightly scheduled to avoid overlap between convoys of different leaders, and Canada’s unified command will manage this sequencing.

In Canada, firearms laws are strict, and foreign security operatives cannot ordinarily carry weapons. However, special legal arrangements are in place for events like the G7 to allow foreign protection officers to be armed. Under Canada’s Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act, the government can grant certain immunities and privileges to foreign representatives and their staff during international conferences. For the 2025 G7, an Order in Council was issued to extend diplomatic-type immunities to summit participants and their necessary staff. This means UK PPOs are treated akin to diplomatic agents for the duration of the event – immune from arrest or local prosecution for actions in the line of duty. In practical terms, their UK-issued sidearms can be carried in Canada legally, as their mission (protecting a head of government) is authorized by the host nation.

Canada’s Office of Protocol and the RCMP coordinate the paperwork allowing foreign security details to import and carry firearms. Foreign representatives must normally apply for a Canadian firearms permit if they wish to carry weapons in Canada, but for high-level visits this process is streamlined via diplomatic channels. The RCMP typically either swears foreign officers in as temporary special constables or provides a written authorization that exempts them from Canadian firearms laws while on duty. There is precedent for this: during the 2010 G20 in Toronto and 2018 G7 in Quebec, visiting leaders’ bodyguards (e.g. U.S. Secret Service, French Gendarmerie GSPR, etc.) were permitted to carry their duty weapons under such agreements. These foreign officers do not have police powers in Canada and remain under RCMP operational oversight, but they can use force to protect their principal as a last resort. Any use-of-force incident would be covered by diplomatic immunity and dealt with at a government-to-government level, not in Canadian courts.

While no public Status of Forces Agreement is needed (these officers are not military), the arrangements are codified in Memoranda of Understanding between Canada and each country’s security service. Details are classified, but they outline rules of engagement, acceptable equipment, and coordination mechanisms. For example, foreign teams might be allowed to carry handguns but not long guns, and may be required to notify the RCMP if they draw or use a weapon. The privileges and immunities Order for the G7 covers “representatives of a foreign state,” which would include official security personnel as part of a leader’s delegation. In essence, UK SO1 officers at the summit have legal cover to operate with firearms, with the understanding that they will abide by Canadian guidelines and only act in protection scenarios. This framework enables them to do their job without hindrance, while Canadian authorities retain overall jurisdiction on security matters.

Each high-level summit has further refined how UK protective and intelligence units cooperate with hosts and allies:

In summary, precedent shows a pattern of close cooperation. Foreign protection units respect the host nation’s lead and legal framework, while hosts accommodate the visiting teams’ requirements (armored cars, armed agents, secure communications, etc.). The UK’s SO1 has worked alongside the RCMP and others in numerous settings, creating an informal network of trust. By the time of the 2025 G7, these patterns mean much of the groundwork – from communication channels to joint response plans – is already in place.

A G7 summit is a prime target for terrorists, so counterterrorism capabilities are on high alert. Canada will deploy its own tactical teams – the RCMP’s Emergency Response Team (ERT) and possibly military special forces (JTF2) – in the Kananaskis area for rapid response to any attack or hostage scenario. The UK delegation will lean on these host-nation resources for heavy intervention, but may also quietly augment its security with specialized personnel. It is plausible that a small number of the Met’s Counter Terrorist Specialist Firearms Officers (CTSFOs) or SAS members accompany the UK party in a covert role. In past summits hosted abroad, the UK has kept a liaison presence from Special Forces or COBRA unit on standby (e.g., at Gleneagles 2005, the security plan explicitly positioned UK special forces at a nearby base ready to deploy). For 2025 in Canada, any UK special operators would operate under Canadian authority if deployed, likely only in extremis (such as an attack directly targeting the UK Prime Minister where immediate action is needed). The routine armed protection is handled by the PPOs, but those officers know they can call on heavier support if needed – either the host’s tactical units or any discreet UK team attached. Notably, the RCMP’s event commander has mentioned preparing for both conventional and “modern security threats such as drones,” and noted recent assassination attempt trends, indicating a comprehensive CT posture that the UK team will integrate with.

Chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threats are a less likely but high-impact danger at summits. Both the UK and Canada are highly attentive to CBRN risks. A leaked Gleneagles G8 briefing showed that authorities evaluated the risk of chemical, biological, and radiological attack in their threat assessments. In Kananaskis 2025, Canada’s military and RCMP will have CBRN detection units and hazardous materials teams deployed on scene. The UK delegation is likely bringing along CBRN expertise as well – for instance, specialist advisers from the UK Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) or counter-WMD units might be attached to the PM’s entourage as liaison. They could carry portable detection gear (to sniff out toxins or radiation in venues) and would coordinate with Canadian CBRN teams on any suspicious incident. The British team also benefits from equipment already in use: the PM’s armored vehicle is “sealed against chemical attack and has its own independent oxygen supply,” a last line of defense if a chemical agent were released. Additionally, the Five Eyes intelligence sharing extends to CBRN warnings – any chatter or intelligence about a possible WMD plot would be immediately shared between CSIS, MI5/MI6, and others before or during the event. Both countries likely have mutual aid plans; for example, if an incident occurred, British specialists could assist the Canadians in investigation or decontamination (as was the case when allies helped each other in past nerve-agent attacks and so forth). In short, robust counterterrorism and CBRN countermeasures are in play, combining UK and Canadian strengths. Summit security drills usually include scenarios like a terrorist assault or a chemical threat, ensuring that UK’s security detail knows how to react in concert with the RCMP and Canadian Forces if the worst-case scenario unfolds.

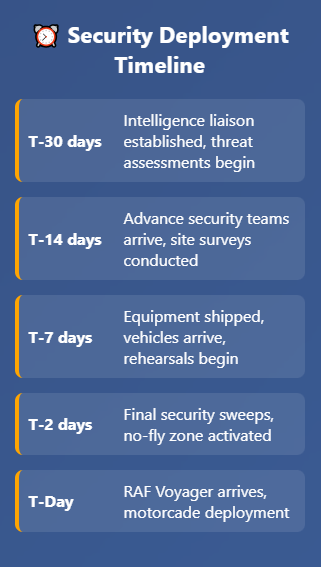

Open-source intelligence analysts can often detect subtle signs of these security preparations in the lead-up to the G7 summit in Kananaskis. Some OSINT indicators to watch for regarding the UK delegation include:

By compiling these open sources, an intelligence analyst can form a comprehensive picture of the UK’s security footprint at the G7. The combination of flight data, local news, procurement info, and official statements provides a multi-faceted OSINT mosaic: we can anticipate the arrival of the RAF Voyager, the presence of a UK motorcade convoy, the legal immunity framework for armed officers, and the behind-the-scenes integration of UK intelligence with Canadian security. Each piece by itself might seem mundane (e.g. a tender for hotel rooms or a news quote about “unified command structure”), but together they point to the extensive and methodical preparations by the UK in partnership with Canada to protect the Prime Minister and delegation during the 2025 Kananaskis G7 Summit.

The UK’s protective deployment to the 2025 G7 Summit in Kananaskis illustrates the precision choreography behind high-level diplomatic security. While Canada maintains overall jurisdiction, the UK brings its own close protection officers, intelligence liaison staff, armored transport assets, and counterterror capabilities — all integrated under Five Eyes cooperation and RCMP oversight. From the RAF Voyager’s arrival in Calgary to the concealed presence of SO1 officers and MI5-CSIS coordination channels, the British footprint is thorough but discreet.

Yet this operation also underscores how even tightly controlled security plans emit open-source signals. From flight tracking to procurement trails, and from diplomatic immunities to motorcade rehearsals, the UK’s presence can be reconstructed by a vigilant observer. In an age of adversarial OSINT, no summit is opaque — not even at 5,000 feet in the Alberta Rockies.

As ever, it’s not just what happens behind the wire that matters — it’s what leaks into the margins. For Britain, Canada, and every G7 participant, the summit is both a diplomatic stage and a security crucible. And like all well-guarded secrets, it begins and ends in the metadata.

Editor’s Note: All of this information is sourced from the public domain and logical inference.