Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

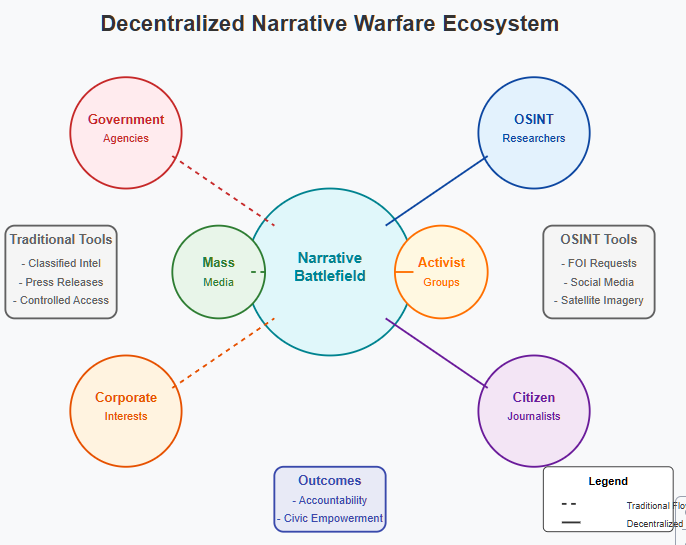

In today’s information environment, narrative warfare refers to the strategic battle over stories and meanings – not just raw data or isolated facts. Traditional information warfare often involves state-run propaganda or disinformation campaigns that push selected facts (or falsehoods) to achieve an agenda. Decentralized narrative warfare, by contrast, is waged across a diffuse network of players rather than a single centralized authority. It is essentially warfare over the meaning of the information. In narrative warfare, controlling the story – the interpretation and context of events – is the ultimate objective. This differs from classic information warfare where the focus might be on controlling the facts themselves; narrative warfare recognizes that how facts are framed or connected can be more persuasive than the facts alone.

In a decentralized model, anyone with internet access and curiosity can become a combatant on the narrative battlefield. Unlike the top-down narratives of the past (e.g. government propaganda broadcasts or one-way mass media messaging), modern narratives emerge from countless independent sources: bloggers, grassroots activists, citizen journalists, and social media influencers all contribute. Legitimacy in this “post-institutional” landscape is polycentric – people are often more inclined to believe stories surfaced by peers, online communities, or influential independent voices than official institutional accounts. This environment creates a complex battleground where narratives compete, intersect, and evolve continuously. Decentralization means there is no single chain of command; instead, narrative alliances form organically around shared evidence or storylines. Such narrative warfare is often self-organizing and dynamic, making it harder for any one authority to control.

Crucially, decentralized narrative warfare is not inherently about deception (though it can be exploited for that). It includes truth-telling and exposure as potent weapons. A compelling true story unearthed by a small group can counter a massive official spin campaign. Narratives built on verified facts carry moral weight and credibility, which can sway public opinion just as powerfully as any misinformation – if not more so. In essence, decentralized narrative warfare democratizes the information battleground: it lowers the barriers to entry so that non-state actors and everyday citizens can influence public discourse on issues of security, policy, and rights.

One of the driving forces behind decentralized narrative warfare is the rise of private OSINT channels – independent actors who gather and analyze Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT). OSINT refers to information collected from publicly available sources (websites, social media, public records, satellite images, news reports, etc.) as opposed to secret or classified data. This means any resourceful individual or group can harness OSINT to produce intelligence. Unlike traditional intelligence confined to government agencies, OSINT is accessible to citizen investigators, journalists, and online communities. The open nature of OSINT “democratizes intelligence gathering”, allowing small organizations and even amateurs to uncover valuable information without expensive infrastructure. For example, many human rights organizations and independent researchers rely on OSINT to document abuses, using nothing more than internet tools and determination.

Private OSINT actors have become influential narrators in their own right. Independent researchers – such as academic labs or even lone analysts on Twitter – routinely dig up data that challenges official accounts. Investigative journalists heavily use OSINT methods like data mining and freedom-of-information requests to break stories. Online communities also collaborate in open investigations: for instance, volunteer networks have crowd-sourced analyses of conflict footage or tracked extremist groups’ online footprints. These actors operate outside of formal hierarchies, yet their findings can shape mainstream narratives when they gain traction.

A striking global example is the Bellingcat collective, a citizen journalism group famous for its crowd-sourced investigations. Bellingcat and similar OSINT collectives have changed the course of public narratives on major geopolitical events. Instead of relying on government briefings, these investigators derive their conclusions entirely from publicly available data feeds. Their hallmark investigations – identifying the perpetrators behind incidents like the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 over Ukraine and the poisoning of former spy Sergei Skripal – provided hard evidence that embarrassed powerful state actors who had tried to cover their tracks with disinformation. In the MH17 case, Bellingcat’s open-source sleuthing traced the missile to Russia-backed separatists, directly countering false narratives and forcing the issue onto the world stage. This demonstrated how even a well-resourced government’s narrative can be upended by civilians armed with OSINT, since even the most sophisticated and security-conscious adversary has weaknesses that can be laid bare by creative OSINT research.

Importantly, OSINT-driven narrative shifts are not confined to war zones or foreign affairs. In the realm of corporate and political accountability, independent OSINT work has similarly made waves. In fact, OSINT has “gone mainstream” as a component of journalism and public debate. Major media outlets now incorporate satellite imagery analysis, leaked database searches, and other open-source methods into their reporting, amplifying the impact of private OSINT findings. For example, The New York Times and other outlets have published investigations of human rights violations (such as the destruction of cultural sites in Western China) underpinned by satellite photos and data analysis originally uncovered through OSINT techniques.

The role of private OSINT actors in shaping narratives can be summarized this way: they supply evidence and analysis that might otherwise remain hidden or inaccessible, thereby injecting new facts and perspectives into public discourse. In doing so, they often challenge official or dominant narratives. Whether it’s citizen journalists exposing human rights abuses by autocratic regimes or online communities documenting the truth of events in real time, these decentralized efforts act as a “beacon of light in an age of disinformation,” undermining attempts to manipulate public perceptions-. The cumulative effect is that public narratives are no longer shaped solely by government and mass media; a determined individual with an internet connection can influence what the public knows and cares about on issues from corruption to conflict.

To see decentralized narrative warfare in action, we can look at Canada as a case study. In Canada, independent researchers and advocacy groups have used tools like Access to Information requests (Canada’s equivalent of FOIA, known as ATIP requests) to pry into government activities and bring secretive practices to light. These efforts show how open-source intelligence gathering by private citizens can expose official conduct, alter the public narrative, and prompt debates about accountability.

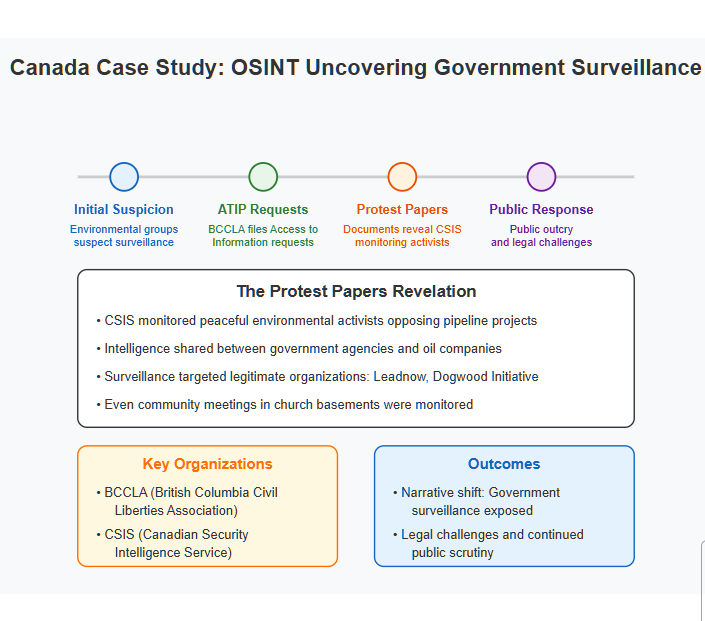

One prominent example began with environmental and civil liberties groups suspecting that federal agencies were spying on lawful activists. Their suspicions were vindicated through what came to be known as the “Protest Papers.” The British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA), along with journalists and allies, filed ATIP requests and pursued complaints that eventually pried loose thousands of pages of documents from Canada’s security agencies. What these documents showed was eye-opening: Canada’s spy service, CSIS, had been routinely monitoring and collecting information on peaceful protesters who opposed major oil pipeline projects. Internal reports even showed that CSIS welcomed and kept reports from energy industry corporate security about activists deemed “threats,” effectively treating concerned citizens as subjects of interest . This surveillance extended to well-known environmental organizations and advocacy groups – including Leadnow, the Dogwood Initiative, and the Council of Canadians – none of whom posed any credible threat to national security.

The ATIP disclosure confirmed what many had only suspected: federal agencies were sharing intelligence with private oil companies about environmentalists, blurring the line between national security and corporate interest. One document revealed that a National Energy Board security official coordinated with CSIS and even mentioned consulting Canada’s signals intelligence agency about a community meeting in a church basement. Far from monitoring violent extremists, the target in that case was a workshop on storytelling and sign-making organized by retirees and local activists. Understandably, these revelations caused a public outcry. As one organizer put it, “Our tax dollars are being used to spy on Canadians to benefit the fossil fuel industry,” raising the question of whether authorities were more interested in protecting corporate infrastructure than citizens’ rights.

When the Protest Papers became public, they quickly shifted the narrative in Canada about security and dissent. Government agencies like CSIS had long maintained that they only surveil real threats – terrorists, foreign spies, and the like – but here was concrete evidence that peaceful domestic critics were swept up in surveillance efforts. The official narrative of “we only target threats” began to crumble under the weight of emails and reports showing agents treating grandmothers with protest signs as persons of interest. This decentralized narrative offensive – catalyzed by private citizens armed with public records – forced a national conversation: What are the proper limits of surveillance in a democracy? Who gets labeled a threat, and who decides?

It’s important to note that these disclosures did not come from a government press release or a parliamentary inquiry. They emerged because private actors used Canada’s transparency laws to obtain information the government wasn’t willing to volunteer. Access to Information laws were invoked by citizens to demand accountability and pull back the curtain on state surveillance. This underscores a broader point: freedom of information (FOI) is itself a tool of narrative warfare. By design, FOI mechanisms like ATIP empower the public to get at the truth. Indeed, transparency advocates note that FOI is “a standard tool for increasing transparency and reducing corruption,” widely recognized as a basic democratic right that helps make government institutions more accountable. Canada’s case demonstrates that when determined citizens wield that tool effectively, they can rewrite the public narrative surrounding government conduct – in this instance, changing the story from “we don’t spy on law-abiding people” to “here is proof that you did, and here’s why it’s a problem.”

The impact of these revelations in Canada went beyond just embarrassment for the agencies involved. They triggered legal challenges and public scrutiny. The BCCLA filed complaints and eventually a court case arguing that CSIS overstepped its mandate by monitoring groups like Dogwood Initiative and sharing info with oil industry executives. Although an oversight body initially dismissed the complaint (accepting CSIS’s claim that any surveillance of protesters was incidental to investigating other threats), the released documents fueled ongoing litigation and debate. Civil society didn’t drop the issue, and media outlets kept the story alive, pressing officials to explain themselves. This is a classic outcome of decentralized narrative warfare: what starts as a small-scale disclosure by an independent actor evolves into a sustained public narrative that those in power must address.

Canada has seen other instances of private OSINT efforts bringing surveillance to light as well. Journalists and researchers have used ATIP requests to uncover, for example, how the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) have monitored social media during pipeline protests and lacked clear policies on handling that data. In one case, a watchdog report found the RCMP had collected personal information from Facebook and other open sources without guidelines, and recommended they institute stricter rules – highlighting that even police OSINT gathering needs oversight to protect civil liberties. And in a very recent development, a Canadian research group (the Citizen Lab at University of Toronto) used open-source sleuthing to discover evidence that provincial police in Ontario were using powerful spyware tools to hack phones. They matched a spyware company’s digital fingerprints to an Ontario police network address, an OSINT coup that prompted The Guardian and other media to report on this previously secret surveillance technique. The police force, once confronted, had to issue statements defending its practices as lawful. Here again, an independent investigation using public data suddenly thrust a new narrative into public view: police high-tech surveillance of Canadians.

These Canadian examples illustrate how a few documents or data points in the hands of independent actors can punch far above their weight. A single ATIP release or OSINT finding can snowball into national news, parliamentary debate, or changes in policy. In narrative terms, what’s happened is that the frame of discussion shifts from “trust us, everything is under control” to “wait, what exactly have you been doing behind closed doors?” The authority over the narrative moves, at least temporarily, from officials to citizens. And importantly, this narrative shift is powered by evidence – emails, technical data, surveillance reports – that gives the new narrative credibility and bite.

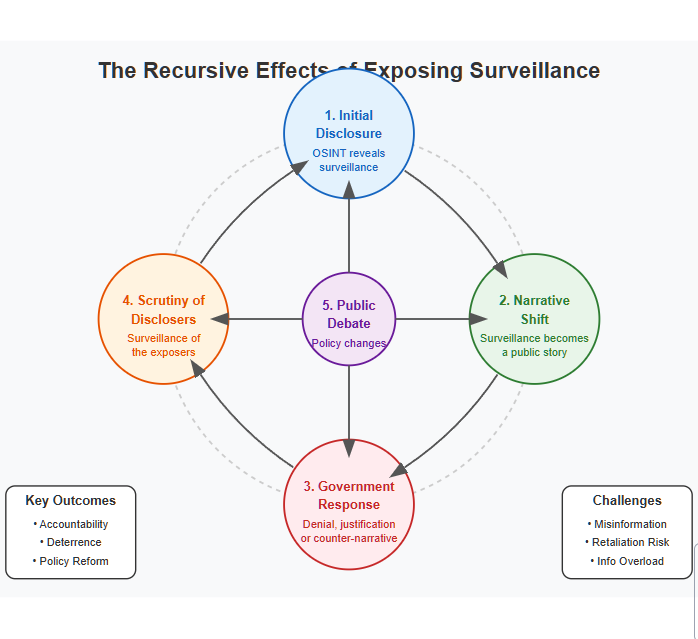

An intriguing aspect of this dynamic is how publishing evidence of surveillance can trigger recursive effects. In other words, the act of exposure itself becomes a new element in the ongoing narrative contest – and even a potential target for further surveillance. When independent investigators disclose that a government has been spying on its citizens, several recursive outcomes typically follow:

First, the fact that surveillance was happening (previously secret) becomes a major story in its own right. Public discourse shifts to focus on the watchdogs and whistleblowers. For example, after the Canadian Protest Papers came out, the media narrative wasn’t just “CSIS spied on environmentalists.” It also became “Civil liberties group reveals spy agency overreach.” The narrative spotlight moved onto the actions of the BCCLA and the journalists who brought the documents forward, casting them as protagonists in a democratic drama. In decentralized narrative warfare, this is a win for the private OSINT actors: they have successfully introduced a new storyline that authorities now have to react to.

Predictably, once such disclosures surface, government agencies often scramble to control the damage. This can involve launching counter-narratives – for instance, downplaying the significance of the exposed surveillance or framing it as necessary and legal. In the Canadian case, officials responded that any monitoring of protesters was merely a by-product of legitimate investigations and not aimed at suppressing dissent. This defensive narrative is an attempt to reassure the public (and legislators) that nothing improper occurred. In doing so, agencies may selectively quote laws or oversight findings (such as the initial complaint dismissal by the surveillance review committee) to validate their story. Thus, a tug-of-war ensues: independent OSINT actors push the narrative of “unjustified surveillance,” while authorities counter with “we only did what was necessary.” Each side is effectively weaponizing information – one side using leaked or obtained evidence, the other using institutional authority and spin – to sway public perception.

A more insidious recursive effect is that those who expose surveillance sometimes themselves become subjects of interest. History has shown that whistleblowers and investigative journalists can end up in the crosshairs of the state. While democratic countries like Canada don’t typically prosecute FOI requesters, there have been instances of subtle retaliation or monitoring. In fact, people who regularly file access-to-information requests often express “legitimate fears of back-tracing and retaliation” by officials. Prime Rogue Inc has experienced such retaliation on the part of the Canadian government. In the ATIP context, this could be as simple as bureaucrats sharing the identities of frequent requesters across departments (flagging them as “troublemakers”), or as serious as targeted surveillance of the leakers of information. The exposure of surveillance thus can lead to more surveillance – of the exposers themselves. This creates a chilling effect that can deter others from coming forward. It’s a paradox: using transparency tools to reveal abuse can paint a target on the backs of those citizens using them. For example, if a journalist uses OSINT to reveal a controversial police program, the police might start quietly scrutinizing that journalist’s social media or digging into their background. The watcher doesn’t like to be watched, and may respond by intensifying information-gathering on the new “threat” – namely, the people who blew its cover.

On a more positive note, once surveillance practices are dragged into the open, it often triggers broader public debate and sometimes policy reforms. The disclosure’s narrative might recursively inspire new actors to join the fray – academics may publish analyses of the incident, advocacy groups might launch campaigns or petitions, and regular citizens become more aware and vocal. In Canada, for instance, after the surveillance of pipeline protesters became public, members of Parliament questioned the agencies involved, and Canada’s new oversight bodies (like the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency, created in 2019) faced pressure to look into the matter. The narrative of “surveillance of activists” bred new narratives around “strengthening oversight” and “protecting the right to protest.” In some cases, the government may even adjust its behavior in response – not necessarily out of goodwill, but because the exposure raised the costs of continuing as before. Knowing that they could be exposed again can lead agencies to scale back certain surveillance programs, tighten their own secrecy, or conversely, to double-down but with more caution. In any event, the initial act of exposure doesn’t end the story – it begins a new chapter.

Finally, the disclosure and its fallout become part of the ongoing feedback loop in narrative warfare. Governments will monitor how the story develops in the press and on social media – essentially performing OSINT on the public’s reaction to their own misconduct. This helps them gauge how much damage is done and whether they need to further intervene in the narrative (for example, by releasing previously secret information to contextualize their actions, or by initiating PR campaigns about how they respect civil liberties). On the other side, the activists and researchers who made the disclosure remain alert, watching for any sign of retaliation or for new information that can bolster their claims. Each side is effectively performing surveillance – one in a metaphorical sense of narrative surveillance, the other sometimes quite literally – on the evolving situation. The result is a recursive cycle of watchfulness: once a cat-and-mouse game of surveillance is exposed, the mice keep an eye on the cat and the cat keeps an eye on the mice.

In summary, exposing surveillance through decentralized OSINT channels tends to set off a chain reaction. The initial revelation alters the narrative terrain, prompting reactions and counter-reactions that can echo for years. The disclosure doesn’t shut down the conflict between privacy and security – it amplifies it by adding new actors (the disclosers and their supporters) and new information into the fray. This self-referential cycle is a hallmark of modern narrative warfare: information begets narrative, which begets more information-gathering in response. It’s a reminder that in the digital age, no narrative is ever truly settled – once information is released into the wild, it can trigger cascading effects that loop back into the original issue in unexpected ways.

Despite the challenges and friction it can generate, decentralized narrative warfare through private OSINT yields several strategic benefits for society. These benefits strengthen democratic accountability and can even enhance security in the long run by correcting abuses of power. Key advantages include civic empowerment, accountability, and strategic deterrence of wrongdoing.

Perhaps the most immediate benefit is the empowerment of ordinary citizens and civil society. The democratization of intelligence means that people are not helpless in the face of complex issues – they can investigate and engage. The availability of OSINT tools and public records allows citizens to “collect valuable data without financial or bureaucratic barriers,” putting some investigative power in the hands of the governed rather than reserving it all for the governors. This empowers non-profits, activists, and even small communities to shine a light on issues they care about without needing a major newsroom or an intelligence agency behind them. For example, as noted earlier, human rights groups have harnessed OSINT to document violations, which enables them to raise awareness and demand justice on the global stage. In Canada, the very act of filing ATIP requests or analyzing publicly available data has given citizens a direct way to engage with and impact policy – a form of “do-it-yourself” oversight. This fosters a more informed and active citizenry. When people see that a handful of volunteers can analyze satellite images to expose a secret facility, or that a lone researcher can use public data to reveal government misbehavior, it sends a powerful message: you don’t need to be a high-ranking official to contribute to truth-seeking and reform. In this sense, decentralized narrative warfare is deeply democratic – it invites broader participation in the creation of public knowledge.

Decentralized narrative efforts compel greater accountability from those in power. By leveraging transparency tools, private OSINT actors serve as independent watchdogs. Their work often results in hundreds of media stories that would not exist otherwise. For instance, veteran Canadian researcher Ken Rubin has filed and analyzed thousands of information requests over decades; his efforts have directly led to countless news stories exposing government secrets and missteps. This kind of sustained pressure makes it harder for authorities to act with impunity. When officials know that someone will eventually obtain the paperwork, data, or images of what they’re doing, they must calculate the risk of exposure. Even if they aren’t deterred (more on deterrence shortly), they are at least forced to answer uncomfortable questions in public forums once the information comes out. This is exactly what freedom of information laws were intended to achieve: an increase in transparency such that governments behave more accountably in an age when they hold vast amounts of data and citizens have the right to interrogate that data. The end result is a form of societal self-correction. Wrongdoing or incompetence that would have stayed hidden can be confronted and addressed because decentralized narrators brought evidence to light. In cases where wrongdoing is confirmed, this can lead to policy changes, resignations of officials, or at least a public record that voters and oversight bodies can act upon. Even when information reveals lawful activities, the debate it sparks can lead to tighter laws or better oversight if the public deems the activity overreach (for example, if surveillance was technically legal but seen as overbroad, the outcry can drive reforms).

Another benefit, somewhat indirect but very important, is the deterrence effect on powerful actors who might otherwise be tempted to overreach or violate norms. Simply put, the presence of savvy citizen watchdogs raises the stakes of getting caught. In the past, a government agency might assume that its secret actions would stay secret for decades, if not forever. Now, thanks to open sources and digital connectivity, that agency has to assume that sooner or later, some evidence of its actions could surface. This uncertainty can deter misconduct. A vivid illustration comes from the realm of public protest: the “new ability to track and identify law enforcement wrongdoings during protests” (through smartphones, live streams, and OSINT analysis) has given protesters a “new level of protection, defense, and courage.” Police officers, aware that any excessive force or unlawful behavior might be filmed and shared worldwide, must think twice before acting – the knowledge that the crowd is watching with cameras has a chilling effect on abuses. Translate this principle to broader governance: officials know that journalists or activists might be scrutinizing procurement data for signs of corruption, or that satellite imagery could reveal a secret facility; this possibility can deter blatant malfeasance. Decentralized narrative warriors essentially act as a distributed surveillance network of the public on the powerful, flipping the script of the surveillance state. While it’s not foolproof – bad actors will still attempt bad acts – it raises the potential costs of being caught dramatically.

Moreover, even when deterrence fails and wrongdoing occurs, the fact that OSINT can expose it after the fact still contributes to long-term strategic deterrence. It signals to other would-be offenders that they might not get away with it unscathed. For example, when Bellingcat uncovered the identities of Russian agents involved in an assassination attempt, it not only derailed that specific covert operation’s narrative, but it also sent a message to intelligence operatives globally that their anonymity is not guaranteed. When citizen investigations lead to global sanctions, criminal charges, or just public disgrace (as happened to those GRU agents outed in the Skripal poisoning case), it alters the cost-benefit calculation for future operations. In democratic contexts, revelations of domestic surveillance or corruption can similarly put leaders on notice that they may face career-ending scandals if caught. The deterrence is not absolute, but it introduces a layer of risk that can temper the worst impulses.

Beyond these specific points, decentralized narrative warfare contributes to a healthier information ecosystem by introducing diverse perspectives and independent verification. It challenges the monopoly of any one narrative. In intelligence terms, it’s an open-source “red team” that keeps the official “blue team” honest. Governments and large media can sometimes form an echo chamber, but the injection of OSINT findings – especially when backed by concrete evidence – forces all sides to grapple with reality. Even military and security experts have come to recognize the value: open-source analyses have provided ground truth in fast-moving crises (for example, verifying what’s happening on the ground in conflicts where propaganda is rampant). This means policies and public opinions are more likely to be based on verified facts rather than unchecked claims, which is strategically beneficial for democracies. In short, civic OSINT efforts strengthen resilience against misinformation by ensuring that credible counter-narratives (or simply accurate narratives) are available to challenge false ones.

Finally, from a values perspective, decentralized narrative warfare via OSINT aligns with the principles of transparency and truth. It leverages the idea that an informed public is a safer and freer public. When citizens can access information and craft their own narratives, society gains a collective intelligence that top-down systems lack. In the long run, this can build trust – not necessarily trust in authorities, but trust in the idea that the truth will eventually come out, and that ordinary people have a hand in bringing it out. That faith is crucial for the social contract in any democracy.

While decentralized narrative warfare through private OSINT has clear benefits, it also comes with significant challenges and caveats. An open, crowdsourced approach to shaping narratives is messy. It can produce misinformation, suffer from lack of coordination, and provoke retaliatory actions that raise concerns. For all its promise, this model of information warfare is not without pitfalls.

The same openness that makes OSINT powerful also makes it vulnerable to inaccuracy and manipulation. Because there is no central authority vetting all the content that independent actors produce, the quality and reliability of OSINT findings can vary wildly. Unverified or erroneous information can spread just as quickly as accurate information, and sometimes faster if it’s sensational. Studies have found that a significant portion of crowd-sourced intelligence reports contain at least some incorrect data. Especially in fast-moving political contexts, adversaries or malicious actors can deliberately seed false “open-source” information to mislead the public or waste investigators’ time. A pertinent example occurred during the 2016 U.S. presidential election: various groups used open-source methods (like trawling social media and hacked data dumps) to disseminate fake news stories and conspiracy narratives. These amateur OSINT-ish efforts often lacked rigorous fact-checking, and many participants failed to distinguish legitimate evidence from fabrications, resulting in false narratives that influenced public opinion. This demonstrates a danger: decentralized narrative warfare can be hijacked. Without the gatekeepers of traditional media, lies can sometimes masquerade as “open-source investigations” and gain an audience. In the context of Canada or any democracy, one could imagine, for instance, a group of individuals misinterpreting crime statistics or misusing publicly available data to argue a flawed narrative about a community or a policy, inadvertently fueling baseless fears. The absence of a quality control mechanism means consumers of OSINT-driven stories must exercise caution and critical thinking. In short, the decentralization that empowers truth-finding also lowers the barrier for rumor and propaganda to cloak itself in the veneer of “open-source” credibility. This is a fundamental tension: the democratization of information cuts both ways, empowering truth-tellers and deceivers alike.

Another challenge is that decentralized efforts are, by nature, uncoordinated (or only loosely so). Unlike a centrally planned information campaign, independent actors in narrative warfare might duplicate each other’s work, work at cross purposes, or miss the bigger picture due to focusing on narrow bits of evidence. There is often no overarching strategy guiding disparate OSINT investigations. On one hand, this spontaneity is part of its strength – it’s hard to predict where the next insight will come from. On the other hand, it can lead to fragmentation: lots of data points and mini-narratives that don’t coalesce into a coherent message. For example, in trying to expose government misconduct, ten different people might file ten separate information requests on slightly different aspects of the issue, rather than collaborating on a targeted strategy. They might each uncover pieces of a puzzle but never put them together because they aren’t aware of each other’s work. This lack of coordination can dilute the impact of the narrative. It might also lead to important leads being missed – no single person has the resources to follow every thread. Traditional information warriors (like state agencies) often rely on tight coordination and unified messaging; the decentralized side often has to play catch-up in weaving a compelling story from a cacophony of findings. Online communities have tried to solve this by forming ad-hoc groups (for instance, Reddit forums or Discord channels dedicated to a particular investigation), but these rely on volunteer organization and can be susceptible to infighting or splintering. In essence, herding cats is difficult – and decentralized narrative warfare is a bit like herding thousands of curious cats. Sometimes they pounce effectively together, but other times they scatter in different directions.

As mentioned, those who engage in exposing powerful narratives may face pushback. While outright persecution of OSINT investigators is rarer in open societies than in authoritarian ones, it does happen in subtler forms. This can include harassment, intimidation lawsuits (SLAPP suits), or behind-the-scenes career consequences for whistleblowers. Even the process of filing information requests can put citizens at risk of being “harassed or intimidated” under current systems. In Canada, requesters have reported being asked for extensive personal information and identification when filing ATIPs, and they fear that bureaucrats could misuse or share that data, effectively creating unofficial watchlists. The concern is that a government might track who is frequently requesting sensitive information and then take steps to monitor those individuals’ activities. Retaliation need not be dramatic to be effective – even a hint of surveillance or a veiled threat can cause people to self-censor. In more extreme instances globally, investigative journalists relying on OSINT have been subjected to hacking or public smears to discredit them. States sometimes accuse independent researchers of being tools of foreign governments (ironically mirroring the way researchers expose state actors, the state turns around and paints the researchers as the untrustworthy ones). We saw a bit of this in the Canadian case: when confronted, officials tried to paint the surveillance of activists as minimal and justified, subtly implying that the real wrong was not the spying but perhaps the activists’ own behavior – a rhetorical maneuver that can delegitimize the targets of surveillance (and by extension those who defended them). Internationally, Russian authorities responded to Bellingcat’s revelations by branding them as foreign agents or claiming their work was politically motivated, an attempt to undermine their credibility. So, a caveat for decentralized narrative warriors is that they must be prepared for blowback. Legally, most OSINT activities are within rights – after all, gathering public information is not a crime. But gray areas exist, especially if hackers or leaks get involved alongside pure OSINT. Crossing any legal lines (even unintentionally) can give authorities a pretext to crack down. Thus, those engaging in this work need to be aware of the legal landscape and often take precautions to protect themselves and their sources.

Another issue is that open-source investigations can yield mountains of data. Sifting through and interpreting this data correctly is a major challenge. Misinterpretation can lead to misdirected narratives. For instance, satellite images or statistics might seem to show something incriminating, but without expert analysis, one might draw the wrong conclusion. Government agencies have specialists and context for their intelligence; citizen investigators might not have the same level of expertise or contextual knowledge, leading to mistakes. Furthermore, with everyone free to publish their take, multiple conflicting narratives can arise from the same data set. An example could be different analysts offering varying conclusions from the same set of declassified documents – which one does the public believe? Paradoxically, the transparency that’s supposed to enlighten can sometimes confuse, providing fodder for both sides of a debate to cherry-pick what supports their narrative.

There’s also a delicate balance regarding national security. Governments argue (sometimes legitimately, but rarely so) that certain secrets are necessary. Decentralized exposure of intelligence operations or methods could potentially cause harm if it tips off malicious actors or violates privacy. OSINT investigators themselves grapple with ethics: just because information is open-source doesn’t always mean it’s harmless to publish. For example, identifying a covert operative using open sources might be a journalistic coup, but it could endanger lives or international relations. Independent actors don’t have clear guidelines the way (ideally) official agencies do, so they must rely on personal ethics, which can vary. This means decentralized narrative warfare can sometimes cross lines that society needs to then debate: Did the public’s right to know justify exposing X? This is an ongoing conversation, especially as OSINT techniques become more powerful (facial recognition in crowds, scraping social media for personal data, etc.).

In short, decentralized narrative warfare is a double-edged sword. It harnesses truth and sunlight as weapons, but it can also cast shadows. The very factors that make it innovative – openness, speed, lack of hierarchy – also make it prone to error and abuse. Thus, while we champion the promise of private OSINT and citizen-driven narratives, we must also invest in media literacy and robust norms to navigate the noise. For every citizen investigator revealing a hidden truth, there may be another propagating an unfounded theory. The onus falls on the broader community to scrutinize, verify, and maintain standards of evidence. And for the practitioners, a key caveat is: with power (the power to publish and sway narratives) comes responsibility.

The emergence of decentralized narrative warfare via private OSINT channels represents a profound shift in how information power is distributed in society. No longer is the crafting of public narrative the exclusive province of state propagandists or mass media gatekeepers. Instead, we have entered an era where the truth can come from anywhere, and small actors can have a big impact. A lone activist with an Access to Information document, a geek with a satellite image, or an online collective connecting dots in their spare time – these are the new protagonists in the struggle over what stories society believes.

Canada’s experience, from the surveillance of environmentalists to the Citizen Lab’s spyware revelations, shows both the promise and the tensions of this new paradigm. On one hand, civic actors have never been more empowered to hold the powerful accountable. They operate as a distributed system of checks and balances, one that complements formal oversight with grassroots vigilance. The ability of determined individuals to extract and analyze public information has led to concrete gains in transparency and prompted reforms. It has also fostered a sense of participatory defense of democracy – people realize that they can and should play a role in monitoring the state, not just vice versa.

On the other hand, the battle over narratives has intensified as a result. With more voices in the arena, contestation is constant. States and other entrenched interests are adapting, learning to navigate (or manipulate) the chaotic information space. We see authoritarian regimes flooding social media with their own “OSINT” claims, trying to drown out independent findings. We see democratic governments grappling with how to respond when a group of citizens uncovers something embarrassing – do they come clean, or attempt to discredit the source? The recursive loops of narrative warfare mean that every revelation is also a confrontation, every fact can become a flashpoint.

Moving forward, the key will be to maximize the benefits of decentralization while mitigating its risks. This might involve developing better community norms for OSINT work – a culture of verification, transparency about methods, and collaboration rather than competition among truth-seekers. It might also require legal and institutional changes: stronger whistleblower protections and anti-retaliation measures to protect those who expose information in the public interest, as well as modernized information laws that make accessing truth easier (and perhaps dis-incentivize governments from keeping so many secrets in the first place).

For the general public and experts alike, understanding this phenomenon is crucial. We all live in the middle of multiple narrative battles – about public health, about security, about human rights – and recognizing how decentralized actors shape these battles helps us navigate them. It reminds us to ask: Who is providing the information I’m hearing? What evidence do they have? Are there independent sleuths who confirm or challenge it? Increasingly, on any given issue, there likely will be open-source investigators we can consult. This in itself is a remarkable development: an ecosystem of transparency that, at its best, can converge on truth from many angles.

In conclusion, decentralized narrative warfare driven by private OSINT is a testament to both the empowerment of individuals and the enduring power of narratives. It operates on the belief that information, plus initiative, can challenge even the mightiest institutions. Canada’s case shows that the effort of a few can force an entire government to justify itself in the court of public opinion. That is a powerful check on authority and a safeguard for democracy. Yet, it is also a volatile power, one that must be wielded with care. The invitation of this new paradigm is for more citizens to engage critically and constructively – to become part of the narrative process rather than passive consumers. In doing so, we collectively ensure that the stories which guide our societies are not just the ones fed to us from the top, but those rigorously examined and, when necessary, courageously rewritten from below.

Ultimately, the rise of decentralized narrative warfare signals that the balance of informational power is shifting. It is more spread out, more contested, and more open than ever before. This can be disconcerting – it’s a noisier, less orderly public square. But it is also more free. In that freedom lies the opportunity for truth to surface from unexpected quarters and for ordinary people to have a say in the grand narratives that shape our world. That, in itself, is a narrative worth fighting for. As we move forward, and as Canada faces an existential threat from the United States, decentralized narrative warfare will also be increasingly relevant to Canadian Civil Defence. Artificial Intelligence is also increasingly being weaponized for decentralized narrative warfare, and all practitioners should be aware of this AI weaponization trend.

[…] ontological: to reassert the public as a sovereign intelligence actor in environments saturated by narrative warfare, security theater, and reputation laundering. The civilian eye is not passive — it is […]

[…] destabilizing global actor, wielding outsized military power with near-total impunity and a narrative armor that deflects accountability. This analysis argues that Israel’s fusion of theocratic politics, undeclared nuclear might, […]

[…] – an initiative to which CSIS contributes intelligence. In its 2022 public report, CSIS noted the spread of misinformation and disinformation by state and non-state actors (e.g. during the 2022 protests in Canada) aimed at undermining public trust. Drawing on such […]

[…] isn’t crowd control. It’s narrative control.This guide is for those determined to rupture […]

[…] Canada, as the host, is inclined to frame Kananaskis as a calm sanctuary of high-level diplomacy convening at a moment of peril. Expect opening remarks from Prime Minister Mark Carney emphasizing that the G7’s very convening is a rebuttal to chaos – a sign that dialogue among democracies continues even as conflict rages elsewhere. The messaging will likely stress that the world’s leading economies are united in seeking to de-escalate tensions and uphold international law. However, there is an alternate framing favored particularly by Washington (and quietly by some others): that the summit also serves as a showcase of unified resolve and hard power. This line would underscore that G7 nations are the core of NATO and the free world, and that any aggression – be it Russia in Ukraine or Iran against Israel – will meet a strong, coordinated response. We may see a careful blend of these narratives: for public consumption, an emphasis on peaceful solu… […]

[…] billed as a celebration of “unity” on the forum’s 50th anniversary. In practice, it became a discursive killbox – a hermetically-sealed stage where leaders performed sovereignty and transpare… Behind lofty slogans about “protecting our communities” and “shared prosperity,” Canada’s […]

[…] a leader abruptly walks out of a summit, it is a highly symbolic act loaded with psychological and strategic messaging. What signals are being sent – and to […]

[…] and metaphor to imply far more than he states outright. The technique, a classical form of narrative shaping through information warfare, serves two functions: it sparks interpretation among sympathizers who “get the message,” and […]

[…] The timing and framing suggest these statements are less a literal policy proposal than a form of narrative warfare: Carlson is attempting to redefine Canada as a legitimate target of moral outrage, coercion, and […]