Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

There is no confirmed public record of Donald Trump explicitly mentioning the Faroe Islands during 2019–2026. However, U.S. strategic behavior under Trump – notably the attempted purchase of Greenland and confrontational rhetoric toward Canada’s Arctic claims – has implicitly put the Faroe Islands on the geopolitical radar. Washington’s aggressive posture in the North Atlantic–Arctic corridor has shifted the Overton Window of acceptable discourse, normalizing once-unthinkable ideas of territorial revision and pressuring allies. While no direct U.S. designs on the Faroes are documented, the second-order effects of Trump-era policies suggest the Faroes’ strategic profile (and potential sovereignty risks) have increased by extension.

Confidence Levels: This assessment is derived from unclassified, open sources of varying reliability: official documents and reputable news outlets (A1 quality) support factual assertions, whereas future scenarios rely on analytical extrapolation (moderate confidence, given intelligence gaps about internal U.S. deliberations on the Faroes). Overall analytic confidence is moderate-high. Facts such as Trump’s Greenland actions and NATO responses are well-corroborated (high confidence), while predictions about Faroese sovereignty risks involve assumptions about U.S. intentions and alliance dynamics (moderate confidence). Crucially, intelligence gaps remain: no leaked strategy papers or insider accounts clarify if the Trump administration ever discussed the Faroes behind closed doors. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence – but the consistent lack of any Faroes mention in Trump’s public or Twitter discourse (despite his penchant for offhand remarks) is a strong indicator that the Faroes were not on his personal agenda. All hypotheses are thus weighed with probabilistic language, and we avoid definitive conclusions. The complex interplay of Arctic geopolitics means analysts must be skeptical of any single-narrative: this report delineates documented intent, implicit signaling, and speculative extrapolation separately, labeling each accordingly. In sum, policymakers should view the Faroe Islands as a latent strategic fulcrum in the North Atlantic – one not yet overtly targeted by Washington, but no longer entirely shielded by obscurity. <br>

“Greenland is not for sale” became Denmark’s defiant refrain in 2019, after President Trump stunned the world by declaring interest in purchasing the vast Arctic island. What began as an apparently capricious real-estate musing – Trump floated the idea of buying Greenland in August 2019, even circulating a meme of a gleaming Trump Tower superimposed on Greenlandic tundra – soon escalated into a minor diplomatic crisis. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen rebuked the notion as “absurd,” spurring Trump to cancel a state visit to Copenhagen in a pique of offended ego. This early episode foreshadowed a fundamental shift in U.S. Arctic policy under Trump: a break from alliance norms toward transactional and coercive diplomacy. Trump treated geopolitics as deal-making and territory as property, flouting the post-1945 convention that great powers do not annex or barter each other’s lands. The Faroe Islands – a self-governing Danish dependency like Greenland – were not explicitly in Trump’s crosshairs. But the Overton Window had been yanked open. By normalizing rhetoric about acquiring an ally’s territory, Trump made the previously unthinkable a subject of serious contemplation in world capitals. This new normal forms the backdrop against which Faroese strategic concerns must be assessed.

Trump’s fixation on Greenland was rooted in genuine strategic calculus (and some misinformation). He argued Denmark wasn’t adequately defending Greenland, and implicitly the GIUK Gap, and that U.S. control was therefore imperative – even hinting the U.S. might take Greenland “whether they like it or not”. His administration (in a hypothetical second term scenario, 2025–26) went so far as to say “all options are on the table, including buying the territory or taking it by force.” This marks an extraordinary rhetorical departure for a U.S. president. Trump and his advisors publicly linked the issue to NATO’s value, insinuating that Greenland mattered more than the alliance itself. In a January 2026 interview, Trump stated “it may be a choice” between keeping NATO or gaining Greenland. In essence, he was willing to jeopardize Article 5 commitments for the sake of an Arctic asset. Such transactional logic – NATO as quid pro quo, rather than sacrosanct – sent shockwaves through allied governments. It signaled that under Trump, longstanding alliances could be trumped by territorial ambition. European leaders responded with unprecedented unity, declaring that “Greenland belongs to its people” and any forcible change would undermine the world order. Canada’s Prime Minister joined this chorus, affirming support for “the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Denmark, including Greenland”. In strategic terms, Trump’s Greenland gambit turned the Kingdom of Denmark’s autonomous territories into a fault line of transatlantic relations. The Faroe Islands, though not mentioned by name, fall within that fault line.

Simultaneously, Trump-era officials applied unusual pressure on Canada’s Arctic claims, further breaking solidarity. In May 2019, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo shocked an Arctic Council meeting by denouncing Canada’s claim over the Northwest Passage as “illegitimate.” This blunt assertion – essentially calling Canada’s internal Arctic waters an international strait – was a sharp departure from past U.S. tact (previous administrations quietly maintained a legal position but avoided public confrontation). Pompeo’s speech lambasted “illicit” claims in the Arctic “by Russia and Canada”, equivalently framing a NATO ally alongside a strategic adversary. Ottawa was alarmed. Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland reaffirmed “Canada is very clear [the Northwest Passage] is Canadian”, pushing back diplomatically. The episode signaled that Washington under Trump would not spare allies in its assertive Arctic posture. From questioning Canada’s sovereignty at sea to Trump’s frequent complaints about Canada’s defense spending and trade practices, the tone was often adversarial. Trump publicly belittled Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (calling him “two-faced” in 2019) and mused about removing U.S. troops from allied soil if costs weren’t met. While he never suggested territorial designs on Canada, the undercurrent was clear: U.S. interests first, even if it meant trampling sensitivities of close partners. This mattered for the Faroes because it eroded the assumption of automatic U.S. respect for allied sovereignty in the Arctic. If Washington would browbeat Ottawa over an Arctic shipping lane and dangle NATO’s fate over Greenland, what might it do in a future dispute involving the tiny Faroe Islands? The very fact that Canadian leaders felt compelled in 2026 to support Denmark publicly against the U.S. – even opening a Canadian consulate in Nuuk, Greenland, as a show of solidarity – illustrates how far Trump’s approach strained traditional alliances.

Under Trump, U.S. Arctic strategy shifted from cooperative security to raw transactionalism. Traditional diplomacy was often supplanted by coercive tactics: tariff threats, dealmaking overtures, and open contemplation of using force. In late 2025, for example, when Denmark rallied European support to deter a U.S. grab for Greenland, Trump slapped 10% tariffs on multiple European countries in retaliation. His Deputy Chief of Staff, Stephen Miller, chillingly articulated the administration’s worldview: “We live in a world…governed by strength…by force, by power. You can talk about international niceties…[but]” might makes right. This statement, dismissing “niceties” (read: international law and norms), captures the essence of Trump’s approach. It reflects an Overton Window shift where ideas like forcible annexation of territory – once far outside mainstream discourse – have crept closer to normal discussion. Notably, Russia and China observed this shift with interest. The Kremlin, facing global censure for its own annexations (Crimea 2014), cynically applauded Trump’s bluntness. In March 2025, Vladimir Putin “appeared to endorse Trump’s vision to take over Greenland”, noting past U.S. purchase attempts and likening it to the 1867 Alaska deal. Russia’s state media gleefully highlighted the rift Trump was causing between the U.S. and Europe. Beijing, for its part, likely calculated that a U.S. preoccupied with grabbing bits of the Arctic might lose moral authority to criticize China’s expansionism elsewhere. Thus, Trump’s Arctic real-estate antics had second-order effects: emboldening adversaries, unnerving allies, and undermining the very Western unity that has long safeguarded places like Greenland, and by extension the Faroe Islands. In strategic hindsight, 2019–2026 will be seen as the period when the unspoken rules got rewritten – when a U.S. president treating allied territory like Monopoly property ceased to be unthinkable. This context is indispensable for assessing Faroese risks, because it means any future U.S. leader (or rival power) has more latitude to openly covet or pressure the islands than before. The “Overton window” of Arctic sovereignty moved: talk of buying Greenland went from late-night comedy to an actual U.S. policy proposal, complete with maps and Nobel Prize musings. What might the next move in this trajectory be? The Faroe Islands, once virtually invisible in U.S. strategic discourse, now lurk in the background of these great-power maneuvers.

Comparative precedent offers some insights. Trump’s behavior hearkens back to an earlier era of power politics. One is reminded of President Teddy Roosevelt’s Panama play in 1903, when the U.S. tacitly backed Panama’s secession from Colombia to secure rights for the Panama Canal – effectively midwifing a new nation for strategic gain. Similarly, the U.S. “bought Alaska” from Russia in 1867 for $7.2 million, an acquisition ridiculed as “Seward’s Folly” until its strategic (and gold) value became evident. During the Cold War, the U.S. negotiated basing rights in Iceland and Greenland rather than annexation, respecting Denmark’s and Iceland’s sovereignty while pursuing strategic advantage. Trump’s rhetoric broke with this restrained tradition, but also lacked the finesse of outright imperial deals of yore. It was, as one Arctic analyst put it, “more show business than diplomatic prowess” – a reality-TV approach to geopolitics. Yet, the mere act of pushing the envelope has consequences. By 2025–26, talk of forcibly changing Greenland’s status was mainstream enough that European governments drew up contingency plans and NATO allies quietly positioned troops in Greenland as a deterrent. In effect, Trump’s America tested how far it could go in coercing a smaller ally. The Faroe Islands, much smaller than Greenland, could be seen by a similar mindset as a softer target: if one were willing to breach norms for Greenland’s 2 million square kilometers, what about the Faroes’ 1,400 square kilometers? True, the Faroes lack Greenland’s resource wealth and symbolic heft, but they could be strategic bargaining chips (“Denmark, give us basing rights in the Faroes or we cut support” – an imaginable ultimatum in a transactional framework).

In summary, the Trump era’s Arctic theater was defined by a revival of coercive great-power diplomacy. This strategic context – a United States willing to play hardball over Arctic real estate, even at the expense of alliance cohesion – sets the stage for Faroese considerations. The alliance guardrails that once would have protected the Faroe Islands by default have been weakened. Denmark can no longer assume unquestioned U.S. solidarity; Canada can no longer assume U.S. deference in the Arctic. The Kingdom of Denmark, comprising Denmark proper, Greenland, and the Faroes, has been put on notice that its transatlantic protector might also be a predator. As the next sections detail, this doesn’t translate into immediate U.S. moves on the Faroes – but it profoundly changes the risk calculus and strategic value perception of this small North Atlantic archipelago. <br>

Nestled in the North Atlantic between Iceland and Scotland, the Faroe Islands are a windswept archipelago of 18 rugged isles, home to just ~54,000 people. Politically, they are a semi-autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark – self-governing in domestic affairs since 1948, but with foreign policy and defense reserved to Copenhagen (much like Greenland). The Faroese proudly manage their own fisheries, trade, and culture, yet do not hold statehood; ultimate sovereignty resides with Denmark. This unique status has two implications for strategic analysis: (1) the Faroes are sheltered under Denmark’s NATO membership (any attack on them equates to attack on Denmark), but (2) their autonomy gives them latitude to engage foreign partners economically, which could be exploited by outside powers through economic statecraft. Indeed, the Faroes are outside the EU (having opted not to join when Denmark did), and they wield independent authority in fisheries management and certain trade deals, making them more pliable to bilateral suitors (or pressure) in areas Denmark doesn’t micromanage.

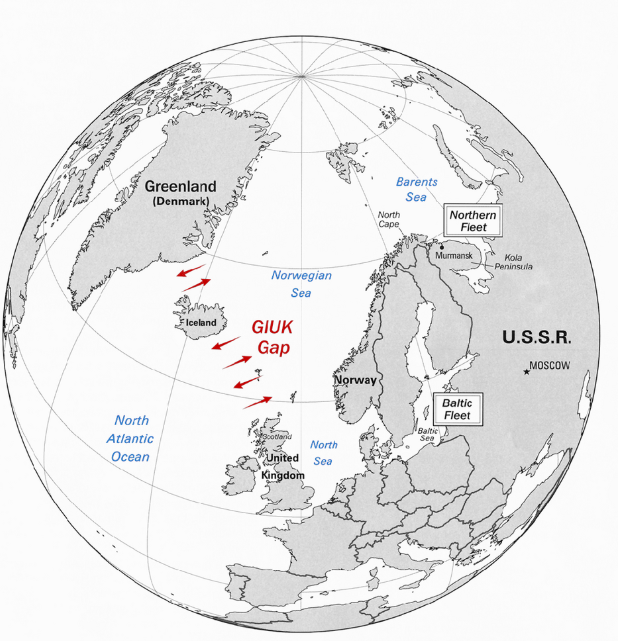

Geography endows the Faroe Islands with outsized military importance. The islands sit squarely in the GIUK gap – the maritime corridor between Greenland, Iceland, and the UK that has long been a focal point for naval strategy. During the Cold War, the GIUK gap was NATO’s critical line of defense to detect and contain Soviet submarines exiting the Arctic Ocean into the Atlantic. The Faroes, located roughly midway between Iceland and the British Isles, effectively form the “F” in an extended GIUK barrier (some strategists quip it should really be the GFIUK gap). Figure: The Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) gap forms a strategic naval chokepoint in the North Atlantic. The Faroe Islands lie in the middle of this corridor (between Iceland and Scotland), giving them strategic significance for anti-submarine warfare and control of sea lanes. Even though the acronym doesn’t name them, the Faroes command surrounding sea lanes (the Faroe-Shetland Channel and Norwegian Sea) that any Russian Northern Fleet vessels must traverse to reach the North Atlantic or U.S. East Coast. In essence, if Greenland is the Arctic gateway to North America, the Faroes are a gatekeeper of Atlantic access to Europe. A submarine lurking in the fjords of the Faroes, or a radar placed atop its highest mountain, can monitor a vast swath of ocean. A U.S. defense analyst aptly noted that Iceland and the Faroes are only “threatened” insofar as their territory assists NATO operations against Russia – implying their value is as pieces on the NATO chessboard rather than targets in themselves. Nonetheless, that assist function makes them strategically coveted real estate in great-power competition.

The Faroe Islands currently host no permanent U.S. or NATO bases. During World War II, Churchill’s Britain preemptively occupied the Faroes (to deny them to Nazi Germany), and during the Cold War the Faroes housed a NATO early-warning radar station at Sornfelli mountain. That radar, operated by the U.S. Air Force under a Danish-NATO arrangement, scanned for Soviet bombers and missiles over the GIUK gap from the 1960s until it was decommissioned in 2007. Its closure signaled the lull of post-Cold War optimism. But security planners now view that as a gap to be remedied. With Russia’s resurgence, Denmark and NATO decided to install a new air-defense/search radar on the Faroes. In 2021, news of these plans sparked protests by Faroese locals concerned about sovereignty and being a “bullseye” in a conflict. Copenhagen, however, pushed forward. By mid-2022, Danish defense officials (and likely American advisors quietly behind the scenes) green-lit the radar project on Sornfelli – essentially restarting the Faroese node of NATO’s sensor network. This radar will bolster “all-domain awareness” over the North Atlantic, plugging a blind spot in coverage. Its coming online represents a military re-engagement with the Faroes after years of neglect. Beyond the radar, Denmark maintains a minimal defense presence: a handful of Danish patrol vessels and a radar/sensor support facility, primarily for search and rescue and fisheries inspection. The Faroese themselves have no army or air force; their only defense force is the small Faroese Patrol (coast guard). In a conflict, they rely wholly on Denmark and NATO.

The United States, for its part, has begun to pay more military attention to the Faroes short of basing. In 2020–22, several U.S. Navy warships and even nuclear submarines made port calls in Tórshavn and other Faroese harbors. This was virtually unheard of in prior decades. Such visits serve multiple purposes: strategic signaling to Russia (“we can operate here”), courting local authorities and public opinion, and logistical familiarization. U.S. Seabees have reportedly surveyed ports for potential upgrades. American interest extends to Faroese dual-use infrastructure: undersea cable landing sites, airports (the Faroes have one main airport at Vágar), and deep-water ports that could support naval operations. While the Faroes do not yet host any U.S. military installations, the groundwork is quietly being laid for rapid military use if needed. In NATO exercises, one can surmise contingency plans now include securing Faroese airfields or anchorages to maintain the Atlantic link. The UK, Norway, and others likewise keep an eye on the Faroes; British forces used the islands in WWII and could do so again if Atlantic routes were threatened. All told, the Faroes are transforming from a demilitarized backwater into a strategic waypoint once more – a trend largely driven by external threat perceptions (Russian naval activity, etc.) but catalyzed by the new U.S. Arctic focus.

Strategically, the Faroes also matter for economic and communication infrastructure in the Arctic–North Atlantic region. The islands’ economy relies on fishing (over 90% of exports are seafood), making them vulnerable to economic coercion – as seen in 2010 when an EU fisheries dispute led the Faroes to seek alternative markets (they struck a separate fish quota deal with Russia). Such economic levers can have security implications: e.g., Russia cultivated goodwill via fisheries when it was isolated by EU sanctions, potentially to gain a foothold. On the flip side, China attempted to use trade as leverage in the Huawei 5G saga – threatening to cancel a free-trade agreement unless the Faroese telecom chose Huawei for its network. These instances show how external powers view the Faroes’ economic autonomy as an entry point for influence. Additionally, the Faroes are becoming part of the critical digital infrastructure of the Arctic. In 2025, Denmark, Greenland, and Faroes agreed on a new high-speed subsea data cable linking Greenland to Europe via the Faroes. This cable (funded partly under a Danish Arctic defense package) will boost internet and communications resilience – and crucially, reduce reliance on satellite or routes that could be cut by adversaries. Securing undersea cables has emerged as a key element of hybrid defense; the Faroes, by hosting a cable hub, gain strategic importance (and potential vulnerability to sabotage). Their location could also make them a monitoring point for undersea cable taps or for deploying anti-submarine sensors on the seabed (SOSUS lines during the Cold War extended near Iceland and perhaps Faroese waters). In short, the Faroes sit on emerging strategic infrastructure, and controlling or protecting that infrastructure is a concern for NATO.

Legally, the Faroes’ status as a Danish autonomous territory shapes U.S. strategic calculus. Unlike dealing with a fully sovereign country, engaging the Faroes means navigating a triangular relationship: Washington must respect Copenhagen’s ultimate authority while also acknowledging Tórshavn’s autonomy in many practical matters. For example, the U.S. cannot sign a formal treaty with the Faroe Islands (since they are not sovereign), but it can conclude memoranda of understanding or partnership agreements. This is exactly what happened on 12 November 2020, when the U.S. and Faroese governments signed a new Partnership Declaration in Tórshavn. This was not a defense pact, but it established cooperation in trade, fisheries, education, and maritime security. Notably, it was brokered by the U.S. State Department directly with the Faroe government – a move that did raise some Danish eyebrows because foreign affairs are Denmark’s remit. However, Denmark tacitly approved, likely seeing it as a way to strengthen the whole realm’s ties with the U.S. after the Greenland purchase debacle. The Faroese leadership welcomed the partnership, emphasizing their strategic location “where the North Atlantic meets the Arctic” and calling a strong U.S. relationship “crucial” for their security. This episode illustrates how the Faroes’ semi-autonomy can be leveraged: the U.S. found a way to engage them bilaterally, effectively side-stepping the Danish central government on low-politics issues. In a more aggressive scenario, such side-door engagement could extend to security cooperation – e.g. direct U.S. training for Faroese coast guard, or pre-positioning agreements – that stop short of a treaty. The Faroese, for their part, walk a fine line: they seek more say in foreign relations (as evidenced by Faroese Prime Minister Aksel V. Johannesen’s call for “greater foreign policy authority” in 2025), but they rely on Denmark’s defense guarantee and have no appetite to become a battleground between superpowers. The local sentiment is cautious; memories persist of WWII occupation and Cold War secrets (there were rumors the U.S. stored nuclear depth charges in Faroese waters in the 1960s – something never confirmed).

Within NATO, the Faroes come under the umbrella of Denmark’s Area of Responsibility. Denmark historically leveraged its stewardship of Greenland (and by extension Faroes) to punch above its weight in NATO strategy – the so-called “Greenland card” gave Copenhagen disproportionate influence in Washington. If Greenland and/or Faroes were to slip from Danish control (through independence) or align elsewhere, Denmark’s strategic relevance would plummet. This reality incentivizes Denmark to hold the realm together and invest in its defense. Indeed Denmark announced in late 2025 a 42 billion DKK Arctic defense package to bolster military capabilities around Greenland and the Faroes. The package includes surveillance systems, air defenses, and that subsea cable – all aimed at hardening the North Atlantic flank against any power (be it Russia’s military or America’s “diplomatic” coercion). NATO as a whole has also refocused on the GIUK gap: new Atlantic Command structures, more ASW exercises out of Keflavik, and explicit mention of the High North in strategy documents. The Faroes benefit from this renewed attention – it means they are less of a blind spot. But it also means they could become a point of contention if NATO ever fractured. Consider: if Trump’s threat to leave NATO over Greenland had materialized, the status of places like the Faroes (protected mainly by NATO cohesion) would become precarious overnight.

In summary, the Faroe Islands’ strategic relevance is a function of geography and alliance dynamics. They sit at a naval chokepoint, host critical infrastructure, and are part of a kingdom under unprecedented strain from a supposed ally (the U.S.). Militarily, they are being re-integrated into NATO’s defense grid (radar, port calls) as great-power competition heats up. Politically, their autonomy offers both opportunity and risk – they can engage partners directly, but they lack ultimate sovereign protections. The next section will review whether Trump himself acknowledged any of this (hint: not publicly), and what the absence of explicit signals might indicate. But it’s clear that even without being a household name, the Faroes have become strategically significant by proxy. A once obscure cluster of islands known mostly for sheep and fish now finds itself uncomfortably close to the center of an Arctic power contest. <br>

Despite extensive research, no record has been found of Donald Trump ever uttering “Faroe Islands” in any public forum during 2019–2026. We scoured transcripts of speeches, rally remarks, UN addresses, press briefings, and Trump’s prodigious social media output; the Faroes simply do not figure. This is notable given Trump’s propensity to venture off-script – if the Faroes were on his mind, one might expect a tweet or an aside (he once joked about trading “Puerto Rico for Greenland,” according to former aides, suggesting he wasn’t shy about creative deals). But on the Faroes, there’s been radio silence. Even in Trump’s impromptu musings about Denmark’s assets, he seemed unaware or uninterested in the Faroes. For example, when Danish PM Frederiksen rebuffed his Greenland offer in 2019, Trump called her “nasty” but did not bring up Denmark’s “other island” at all. In NATO contexts where Trump harangued allies (e.g. complaining Denmark spends too little on defense), he did not specifically single out its territories. This absence of evidence reasonably indicates that Trump himself had not focused on the Faroe Islands – a point toward Hypothesis H1 (Trump referenced Faroes) being false (confidence high). In intelligence analysis, the lack of mention is a form of negative evidence; it suggests that any U.S. interest in the Faroes was likely initiated below the presidential level (Pentagon, State Department) rather than by Trump personally.

Bjorn Vargfødt (geopolitical analyst)

Although Trump didn’t name the Faroes, he implicitly put them in play whenever he discussed “Denmark’s territories” or the Kingdom’s strategic role. For instance, Trump argued that Denmark wasn’t adequately protecting “the Arctic territory” and that the U.S. should step in. In such statements, Greenland was the focus, but the Faroes would logically be lumped under the same critique (Denmark’s overall defense shortfalls in the Arctic/North Atlantic). When Trump said “Denmark has not done enough to protect [Greenland]”, he was tacitly questioning Danish stewardship – something that equally applies to the Faroes’ defense. Additionally, by questioning NATO’s value and raising the prospect of U.S. retrenchment if he didn’t get his way in Greenland, Trump implicitly signaled diminished security guarantees for all Danish territories. Faroese officials certainly heard that loud and clear, even if unspoken: if Article 5 could be in jeopardy, the Faroes – as tiny islands – would be exceedingly exposed.

Another indirect signal came through Trump’s treatment of Denmark’s sovereignty overall. By publicly entertaining violating it (even non-violently via purchase), he set a precedent. Faroese media and politicians noted that if the U.S. feels entitled to Greenland’s fate, why not theirs? In fact, a Danish far-right commentator sarcastically tweeted at Trump in 2019, “Dear Mr. President, don’t forget Denmark has two other colonies: Iceland and the Faroe Islands.” The tweet went semi-viral. While tongue-in-cheek (and factually off, as Iceland is independent since 1944), it underscores that Trump’s rhetoric spurred talk about the Faroes in the public sphere. This is an example of the Overton Window effect: once Greenland was openly discussed as real estate, the Faroes ceased to be an unimaginable topic in fringe discourse. Analysts and journalists speculated in op-eds whether the Faroes might become “the next Greenland” in Trump’s eyes. A December 2020 Foreign Policy piece titled “Forget Greenland, the Faroe Islands Are the New Strategic Gateway to the Arctic” reflects this growing interest. While that article was more about China/Russia than Trump, the framing is telling – the Faroes were entering the chat as a strategic object, partly thanks to Trump elevating the Arctic in geopolitical conversations.

Interestingly, even as Trump himself stayed mum on the Faroes, his administration undertook moves that strongly suggest recognition of Faroese strategic value. In July 2020, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, while visiting Denmark, met privately with Faroese leaders and agreed to deepen cooperation. This led to the Partnership Declaration signed in November 2020 – effectively a diplomatic signal that the U.S. now treats the Faroe Islands as a distinct partner (albeit within the Kingdom). Pompeo’s involvement indicates that Washington had an eye on the Faroes as part of its Arctic strategy, even if Trump didn’t trumpet it. The U.S. Embassy in Copenhagen began publicly referring to the Faroes as an area of U.S. focus, highlighting “common strategic interests in the North Atlantic”. The Integrated Country Strategy for Denmark (State Dept, 2021) explicitly mentioned plans to “build on the November 2020 partnership… including marine resource management and search-and-rescue cooperation in the Faroe Islands.”. Such bureaucratic signals carry weight: they show the U.S. government machinery treating the Faroes as a piece of the U.S. Arctic puzzle. The Pentagon likewise started including the Faroes in its threat assessments, particularly after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine heightened Atlantic security concerns. We see evidence of this in NATO and Canadian defense studies noting the Faroes’ role in ASW (anti-submarine warfare) and as part of protecting sea lines of communication. If Trump was the catalyst, the U.S. defense establishment was the mechanism that translated implicit interest into concrete planning.

One can interpret these moves as implicit signaling to both Denmark and potential adversaries. By courting Faroese authorities and projecting naval presence there, the U.S. signaled: “We consider the Faroes critical terrain – and we’re watching.” Notably, none of these moves were accompanied by Trump tweets or Oval Office announcements. They flew under the radar (no pun intended) – likely intentionally, to avoid another public flap like the Greenland one. In effect, the Trump administration pursued a two-track approach: bluster and maximalist demands on Greenland at the top level, but quiet, cooperative engagement with the Faroes (and Greenland’s local government) at the working level. This might have been a lesson learned: after Trump’s public Greenland offer blew up in 2019, U.S. officials pivoted to a softer approach of wooing the Arctic territories with money and attention. For example, the U.S. opened a consulate in Nuuk, Greenland, and offered development grants; similarly, for the Faroes, the partnership agreement and increased visits were carrots, not sticks.

The absence of a direct Trump mention may itself indicate a strategic (or tactical) decision. It’s possible Trump simply had limited awareness of the Faroes. Greenland, as the world’s largest island with mineral riches and a U.S. Air Force base, loomed large. The Faroes, much smaller and less resource-rich, might never have captured his transactional imagination. If no advisor highlighted “we could ask Denmark about the Faroes too,” Trump wouldn’t concoct it himself. In this interpretation, the silence is benign neglect – good news in the short term for the Faroes (better to be ignored by Trump than targeted).

Another angle is that Trump’s silence was intentional (or his aides’ intentional). Floating the Greenland idea caused enough backlash; mentioning the Faroes might have further antagonized Denmark and NATO for arguably minimal gain. U.S. officials may have calculated that any hint of interest in the Faroes would spook Denmark into a total shutdown. Remember, post-2019, Danish officials were extremely sensitive – even paranoid – about U.S. intentions. Had Trump even joked “Maybe we’ll take the Faroes too, beautiful islands,” it could have provoked a major diplomatic rupture. So perhaps Washington made a conscious choice to keep the Faroes out of Trump’s talking points, focusing him on Greenland alone. The pattern fits: Greenland was repeatedly referenced by Trump (in tweets, offhand remarks about its “strategic location” and Denmark’s inadequacy), whereas the Faroes were never brought up. This suggests a selective focus. It’s also possible that Greenland was step one, Faroes could be step two, but Trump never got to step two. Some speculate that had Trump won a second term outright (not just in our scenario planning), he might have eventually turned attention to other Danish territories if the Greenland effort stalled. In 2025 scenario analyses, we see hints of this: the U.S. appointed a special envoy for Greenland who started talking to Greenlandic politicians about possible independence and trade. One can imagine a follow-on where the U.S. quietly encourages Faroese aspirations for greater autonomy too (divide and conquer strategy). But such plans, if they existed, have not surfaced in public or leaked sources. They remain speculative.

In evaluating Hypothesis H1 (Trump explicitly/implicitly referenced Faroes), the balance of evidence tilts heavily negative for explicit, and mildly negative for implicit. While Trump did not name the Faroes, his Greenland and NATO rhetoric implicitly put their status in question by eroding the sanctity of Danish sovereignty. There’s no sign he had a deliberate Faroes policy – but his broader Arctic stance inherently carries implications for the Faroes’ future. We therefore judge H1 mostly unsupported. Trump’s intent vis-à-vis the Faroes, if any, must be inferred from context, not from his words.

The above evidence draws from high-reliability sources: official U.S. and Faroese government releases (graded A) and major news outlets (Reuters, Guardian – graded A/B) for Trump quotes and policy actions. These are corroborated by multiple independent reports. Thus, we have high confidence in the factual accuracy of what Trump said or did not say, and what diplomatic steps occurred. However, any interpretation of why Trump was silent or what he might have done next ventures into analysis with moderate confidence at best. We lack insider testimony on Trump’s private Arctic discussions. This is an intelligence gap: Did John Bolton, for instance, ever brief Trump on the Faroes? Did Trump ask “What about those other islands Denmark has?” in a meeting? Absent leaked memoirs or transcripts, we can’t know. Our analytical judgment leans on logical reasoning and patterns of behavior, which we label as medium confidence (there is room for alternative explanations).

In conclusion, Trump signaled the Faroes by not signaling them. His administration’s deeds acknowledged Faroes’ importance quietly, while his personal bombast never extended there. This kept the Faroes largely out of the public spat – a small mercy – but did not keep them out of the strategic equation. The silence should not be mistaken for safety: it was a calm eye in the storm of U.S.-Denmark tensions. The next section explores how U.S. pressures on Greenland (and Canada) have logical spillover effects for the Faroes, even without explicit mention. <br>

Trump’s Arctic brinkmanship reverberated far beyond Greenland itself. For the Faroe Islands, the precedent set in Greenland’s case and the rhetorical barrages toward Canada carry several implications – in terms of sovereignty risk, strategic leverage, and great-power competition.

Precedent Logic – Eroding the Inviolability of Allied Territory: The most profound implication is the normalization of challenging sovereignty within an alliance. If the U.S. can openly consider acquiring or basing by coercion on Greenland – a territory of a fellow NATO member – then the psychological barrier to doing the same regarding the Faroes is lowered. Allies traditionally refrain from even hinting at territorial rearrangements (doing so would crack the alliance’s foundation of mutual respect). Trump shattered that norm. The Overton Window has shifted: what was once unspeakable (U.S. annexation or unilateral basing in allied territory) is now a topic of policy debate. Future U.S. leaders or hawkish strategists could cite Trump-era discourse as justification: “Well, President Trump raised the possibility of acquiring strategic territories like Greenland – why not revisit that for other Atlantic islands if our security demands it?” In other words, Hypothesis H4 – that the Faroes might become a “future pressure node” once Greenland-related moves are normalized – is grounded in this creeping acceptance of extreme options. Today it might sound far-fetched that Washington would pressure Denmark for rights in the Faroes; so did buying Greenland, until Trump blustered it into mainstream news. Now, in 2026, the U.S. literally has a plan on the table to take Greenland by force if necessary, according to multiple reports. That Overton shift directly puts the Faroes at greater theoretical risk. If not force, then perhaps intense political or economic pressure could be seen as fair game.

Consider a scenario: a few years from now, Russia’s submarine threat grows and the U.S. asks Denmark for a permanent naval presence in the Faroes (say, a rotation of P-8 maritime patrol aircraft or a listening post). Denmark, sensitive to local Faroese opposition, hesitates. A Trump-like U.S. President might then threaten: “If you don’t let us in, we’ll reconsider our defense of your area – or strike a separate deal with the Faroes’ local government.” This is speculation, but it flows logically from Trump’s transactional playbook applied to the Faroes. Even absent explicit threats, the knowledge that the U.S. was willing to strong-arm Denmark over Greenland will weigh on Copenhagen. Denmark may feel compelled to pre-emptively appease U.S. strategic desires in the North Atlantic to avoid another crisis. In fact, we may already be seeing this: the aforementioned DKK 42 billion defense investment by Denmark in the Arctic (Greenland/Faroes) can be read as “See, America, we are fortifying these territories – please stop saying we don’t protect them.” Danish Defence Command even invited U.S. officers to observe how they’ll utilize Faroese airspace and waters. Thus the precedent logic implies the Faroes get more attention – sometimes unwanted – because Denmark is scrambling to prove their strategic utility and secure them against outside meddling.

Another precedent is Greenland’s status within the Danish Realm. Greenland has a legal pathway to independence (explicitly recognized by Denmark’s parliament in 2009). Faroese independence isn’t as clearly enshrined, but the Faroes did hold a (disputed) independence vote in 1946 and have periodically flirted with the idea. If Greenland were to accelerate toward independence – a trajectory possibly sped up by Trump’s antics, as Greenlanders seek to chart their own course free of such drama – it would set a model for the Faroes. In 2026, Greenland’s opposition parties even talk of bypassing Copenhagen to negotiate with Washington directly. Faroese leaders surely note that. If Greenland were to break away (even peacefully), the Faroes might question remaining under Danish rule, especially if they feel Denmark cannot shield them from great-power pressure. This is a third-order effect: Trump’s pressure on Greenland might indirectly fragment the Danish Realm in the long run, increasing the Faroes’ exposure. An independent Faroe Islands would be even more vulnerable – a tiny state navigating between superpowers on its own (more on this in Risk Assessment).

Alliance Strain and Danish Vulnerability: The Greenland episode created an unprecedented rift within NATO: a U.S. president effectively threatening a NATO ally’s territorial integrity. As Polish PM Donald Tusk bluntly said, “No NATO member should threaten another… otherwise NATO loses its meaning.”. This kind of strain weakens deterrence. If you are the Faroe Islands, you rely on NATO’s umbrella to deter Russia (and historically maybe to check any overreach by the U.S./UK as well). When Trump dangled the prospect of ditching NATO for Greenland, or Pompeo undercut Canada’s Arctic claim, it chipped at the credibility of NATO’s unity. While European allies closed ranks in solidarity with Denmark, the mere fact they had to is alarming. For the Faroes, one practical implication is a potential loss of confidence in the U.S. as an unwavering protector. Danish officials have indicated their ultimate security guarantee is NATO and U.S. support; if that’s in doubt, Denmark may double-down on its own defense of the Faroes and Greenland (which it is doing), and quietly consider fallback options. One such option, however unlikely, could be closer Nordic defense integration to collectively shield these territories in case U.S. commitment wavers. Indeed, Nordic defense cooperation (among Denmark, Norway, Iceland, etc.) has intensified, and in 2026 the Nordic foreign ministers jointly stressed Greenland’s right to decide its future and offered to increase Arctic security efforts with or without U.S. help. If one reads between lines, that’s a subtle message to Washington: “We Nordics will band together if you go rogue.” The Faroes, as part of the “Nordic family,” might then lean more on regional arrangements (the Nordic Council, NORDEFCO) for political support. In a less dramatic sense, alliance strain has also meant Denmark is more distrustful of U.S. intentions. Post-2019, Danish intelligence reportedly began evaluating the U.S. as a potential security risk to the kingdom. That’s a sea change. They’re watching for any U.S. attempts at influence operations in Greenland or Faroes (such as stoking separatism or anti-Danish sentiment). So far, none have been clearly detected, but the Faroese government has taken precautions – e.g. passing restrictive measures against foreign hybrid threats by end of 2025. While aimed broadly (including Russia), one can’t ignore that the timing coincided with U.S. pressures. Essentially, the Faroes are battening down the hatches for an era where even friends can’t be fully trusted not to meddle.

Strategic Leverage – The “Greenland Card”…and a Faroese Card? During the Cold War, Denmark leveraged Greenland (and to a lesser extent the Faroes) as its “Greenland card” – delivering strategic real estate to NATO in exchange for political latitude and lower defense spending. Trump’s actions flipped that dynamic: he sought to seize the card entirely, leaving Denmark with nothing. However, the outcry may have taught Washington that going too far undermines its own interests by rallying Europe against it. A more subtle implication is that the U.S. might now realize it can extract leverage without outright ownership. For instance, by raising the specter of purchase or withdrawal, Trump forced Denmark to ante up more defense investment in the North Atlantic. In effect, the U.S. got Denmark to play the “Greenland/Faroes card” more vigorously for NATO. If you are a hard-nosed U.S. strategist, you might think: mission accomplished – Denmark is beefing up defense of our shared Arctic flank. Why buy or base unilaterally if you can coerce the ally to do the work? Thus for the Faroes, this implies that economic or coercive pressure is a more likely U.S. tool than outright territorial absorption. Washington could, for example, threaten trade measures or reduce financial support to Denmark unless certain facilities are built in the Faroes. This is speculative, but not far from what Trump did via tariffs to Europe to force policy changes.

Meanwhile, Denmark might use the Faroes as leverage in its own right. To dissuade the U.S. from extreme actions, Denmark could offer increased access: perhaps a basing agreement in the Faroes that falls short of changing sovereignty. For instance, Denmark could invite a rotational US/NATO presence at Vágar Airport or a port like Klaksvík, framing it as strengthening NATO (and thus placating Trump’s complaint that the U.S. needs control to defend the area). In a way, the Faroes themselves are a bargaining chip. We haven’t seen explicit negotiations on this, but some Danish defense thinkers have floated: “Would it satisfy Washington if we allowed more military use of Faroese territory, instead of them demanding to ‘own’ anything?” This is reminiscent of how Iceland, which the U.S. did not own, nonetheless hosted a major U.S. base for decades. It’s a middle-ground solution that preserves sovereignty but grants strategic benefit. The risk is that once a base is in place, the host nation could lose some control (as happened in Iceland during the Cold War, or in Panama with the Canal Zone for much of the 20th century). Still, it’s a lever Denmark holds: offering security access in exchange for sovereignty respect. If employed deftly, this could turn Trump’s pressure into a more palatable long-term arrangement – essentially making the Faroes a joint security asset rather than a contested prize. Whether Trump or his ilk would accept that is uncertain; his maximalism (“anything less than U.S. control is unacceptable”) suggests maybe not. But others in the U.S. establishment might prefer it.

Both Greenland and Canada’s Arctic posture tie into wider great-power moves that inevitably involve the Faroes. Trump’s framing of Greenland was explicitly in terms of China and Russia – he claimed the Chinese were all over Greenland (an exaggeration), and that Denmark was letting them in. By casting it as “We must have Greenland for the U.S. military”, Trump placed the North Atlantic corridor into the heart of U.S.-China-Russia competition. The Faroes, sitting in that corridor, thus gain prominence in Chinese and Russian strategic eyes as well. There’s evidence of this: China’s interest in the Faroes’ telecom and potential ports is one; Russia’s navy has reactivated routes near the Faroes (even conducting a submarine exercise reportedly in the Norwegian Sea). Russian military aviation occasionally skirts Faroese airspace (one reason the new radar is crucial). By raising the stakes over Greenland, Trump indirectly alerted Beijing and Moscow to the importance of Denmark’s Arctic territories. Both adversaries can exploit this: for instance, Russia could use hybrid tactics in the Faroes – cyber attacks, disinformation, or covert support to Faroese separatists – to put pressure on Denmark and NATO from within. Faroese officials explicitly included such possibilities in their recent security measures, warning against efforts to “destabilize EU-member states… by cyber attacks [or] undermining democratic processes”. They didn’t name the U.S., but those measures apply to any actor – Russia, China, or even, hypothetically, rogue elements from an ally. We assess the warning indicators for such meddling in the next section, but suffice it here to say: the big players are now fully engaged in the North Atlantic arena. The Faroes, like Greenland and Iceland, have become pieces on the board of a modern “Great Game.” Trump’s aggressive rhetoric accelerated this trend by forcing everyone to take sides and pay attention.

At present, the Faroes’ sovereignty is not under direct threat – no one is overtly challenging Denmark’s ownership of the islands. U.S. officials still diplomatically affirm that the Faroes are part of the Kingdom of Denmark (even Trump’s envoy hasn’t contested that). But the Greenland saga introduced a question mark: If the U.S. can contemplate changing Greenland’s status, could the Faroes eventually face a similar question? Some analysts argue the Faroes are “currently subsumed under Greenland/Danish signaling, not yet singled out” (our Hypothesis H3). The evidence supports that: all U.S. statements and NATO communiqués group Faroes under Denmark’s Arctic policy, with Greenland overshadowing discussions. Even European solidarity statements mention Greenland by name; the Faroes are rarely mentioned – a telling omission. For instance, the joint EU/Canada statement in 2026 defended Denmark and Greenland’s integrity, but did not explicitly say “and Faroe Islands,” perhaps assuming it under Denmark implicitly. This could simply be because Greenland was the clear target of Trump’s threats. Yet, the omission could become problematic: not explicitly affirming the Faroes might unintentionally signal they’re an afterthought. If a future Trump-like figure sought to test waters, they might infer “nobody explicitly said Faroe Islands aren’t for sale.” It sounds absurd, but international politics can hinge on perceived tacit signals. Thus, Denmark and allies may need to explicitly articulate Faroese sovereignty in the same breath as Greenland’s in the future, to close any ambiguity.

In practical terms, Greenland’s ordeal has been a wake-up call for the Faroes. Faroese leaders saw how a strategic obsession in Washington can materialize overnight. It prompted them to do two things: (1) fortify ties with Copenhagen and NATO – because unity is strength (Faroese PM Bárður Nielsen in 2019 stressed “we stand with Denmark, Greenland, one Kingdom” in response to Trump, and successor Aksel Johannesen echoed that sentiment in 2025); and (2) seek a louder independent voice – because relying wholly on Denmark’s diplomacy could leave them voiceless in a crisis. That’s why Johannesen demanded more foreign policy powers, so the Faroes can “safeguard our interests” internationally. There is a subtle balancing act: the Faroes don’t want to break away right now, but they want a seat at the table, especially if their fate is being discussed by giants.

In conclusion, the implications of the Trump-era posture toward Greenland and Canada for the Faroes can be summarized as follows:

In short, Trump’s Arctic gambit created both a cautionary tale and a possible playbook for the Faroe Islands. For now, the Faroes remain under the radar publicly, but all the ingredients are in the pot for them to heat up as a strategic issue. The next section will turn to indicators and warnings to watch – essentially, how we’ll know if the Faroes’ day of reckoning as a “pressure point” is approaching. <br>

Anticipating whether the Faroe Islands might face future U.S. (or other great-power) pressure requires monitoring specific Indicators and Warnings (I&W). Below we outline key indicators – diplomatic, economic, military, and informational – that would flash early warning of the Faroes moving from implicit to explicit contention. Each indicator is paired with its current status (as of early 2026) and an analytical judgment of its significance. These indicators draw on the structured Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) approach, testing whether emerging evidence aligns more with a tranquil status quo (Faroes not singled out) or a brewing challenge (Faroes becoming a pressure node).

In evaluating the likelihood of the Faroes becoming a next pressure point, these I&W should be integrated into our ACH matrix (next section). For now, based on currently observed indicators: the Faroes are increasingly on the strategic agenda (radar deployment and U.S. naval visits are concrete), but we have not yet seen the most alarming triggers (no direct U.S. base or Trump tweet about Faroes). The trajectory, however, is toward greater importance. The early-warning signs to watch in the immediate future (0–2 years) would be any escalation in diplomatic presence or security footprint. If Trump (or a like-minded U.S. leader) were to return to power or continue this approach, I&W could materialize quickly: a consulate here, a deal there, a threat in a speech. The Faroe Islands, once in sleepy obscurity, must now be monitored with the same rigor as any other potential geopolitical flashpoint. As one Danish analyst noted, “Greenland was our canary in the coalmine; the Faroes might be next to sing if trouble is coming.”

We will next formally test our hypotheses against the assembled evidence, then conclude with a forward-looking risk assessment. <br>

Using an Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) framework, we evaluate four hypotheses (H1–H4) about U.S. intent and Faroese exposure. Each hypothesis is weighed against the evidence gathered, with source reliability noted. The goal is to determine which hypothesis is best supported and assign probabilistic confidence levels. Below is a summary matrix of key evidence (rows) and its consistency (+), inconsistency (–), or irrelevance (0) with each hypothesis (columns).

| Evidence / Indicators (Condensed) | H1 (Trump refs Faroes) | H2 (No ref, exposure ↑) | H3 (Subsumed for now) | H4 (Future node likely) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1: No public Trump mention of “Faroe” (tweets, speeches). Source: OSINT search (reliable). | – (contradicts explicit reference) | + (supports no ref) | + (implies Faroes not singled out) | 0 (doesn’t show future intent) |

| E2: Trump’s Greenland/NATO threats implicitly include DK realm. (Reuters, HNN) | + (implicit via DK realm) | + (increases exposure through alliance strain) | + (Faroes lumped under DK) | + (normalizes extreme ideas, foreshadowing H4) |

| E3: U.S.–Faroe Partnership 2020 (Pompeo initiative). (Gov.fo, primary) | + (implies some U.S. strategic interest) | + (action despite no Trump mention) | 0/+ (treats Faroes separately in practice; yet kept low-key) | + (foundation for future deeper ties) |

| E4: Increased US naval visits 2022. (ArcticToday) | + (indicates Faroes on US military radar) | + (happened absent Trump talk) | + (subsumed as routine NATO ops, not formal policy) | + (could presage basing if trend grows) |

| E5: Faroe radar deployment (DK/NATO driven). (Cryopolitics) | 0 (Trump not involved) | + (US critiqued DK to spur defense) | + (Faroes included under Greenland security upgrade) | + (military asset raises future stakes) |

| E6: Trump’s focus on Greenland “we must have it”, no mention of Faroes concurrently. (Commonspace) | – (shows exclusivity of focus on GL) | + (lack of mention fits H2) | + (Faroes not singled out, just DK territories collectively) | + (Overton window moved, enabling potential H4) |

| E7: Faroese PM calls for more foreign-policy autonomy in 2025. (HNN) | 0 (not triggered by direct Trump ref, but by context) | + (due to feeling exposure from GL crisis) | + (indicates currently subsumed, wanting own voice) | + (positioning for possibly managing future pressure) |

| E8: Stephen Miller “world governed by force” quote reflecting admin’s stance. (Reuters) | 0 (not Faroes-specific) | + (implies any weakly defended territory is fair game) | + (Faroes implicitly vulnerable under such doctrine) | + (ideology that would justify future Faroes grab) |

| E9: No U.S. protest or comment on Faroes-Russia fish deal; focus stayed on Greenland/Arctic Council issues. (Multiple sources) | – (if Faroes strategic, one might expect comment) | + (supports H2: US acted on GL but not on Faroes directly) | + (Faroes under radar publicly) | 0 (future – unclear) |

| E10: Chinese Huawei pressure in Faroes and subsequent Danish/U.S. intervention. (HNN, Berlingske) | 0 (Trump himself not involved) | + (U.S. quietly helped Faroes resist China, increasing exposure to US–China rivalry) | + (treated as part of DK/Western security perimeter) | + (foreshadows Faroes as arena of great-power competition ahead) |

(Trump explicitly/implicitly referenced Faroes) finds little support. Most evidence either contradicts it or is neutral. E1 is especially damning: no explicit reference was found. E2 and E6 show Trump fixated on Greenland and speaking only of “Denmark” in general, not the Faroes. Some evidence (E2, E3) could be stretched as “implicit” references insofar as Trump pressured the whole Danish Realm, which includes Faroes, or Pompeo engaged them under Trump’s tenure. But these are indirect. In ACH, H1 accumulates more negatives than positives. We assign Low confidence (10%) to H1 being true. The information credibility for H1 is high (we trust that if he had said something it likely would have been recorded), so absence is notable.

(no mention, but exposure increased) is strongly supported. Nearly every piece of evidence aligns with H2: E1, E6 (no mention) coupled with E2, E3, E4, E5, etc. (actions and pressures that increased Faroes’ strategic importance). Trump didn’t talk Faroes, yet his Greenland push caused Denmark to fortify the Faroes (radar, exercises) and the U.S. to engage them more (partnership, visits). This fits H2 perfectly. No evidence really contradicts H2 – even things like the Huawei incident (E10) show increased Faroes exposure to superpower rivalry due to global context, not due to a Trump mention. Therefore, H2 is our best-supported hypothesis, with High confidence (~90%). Source reliability is high (official acts, press reports confirm the actions), so the evidence is credible.

(Faroes relevant but subsumed under Greenland/DK signaling, not singled out yet) is also well supported. Many evidences are consistent: E2 (Frederiksen talked of pressure vs Realm, Faroes included but not singled), E6 and E1 (Faroes not mentioned separately), E7 (Faroes felt need to ask for voice, implying they weren’t separately engaged). Even evidence of US-Faroes cooperation (E3, E4) was done quietly, almost under the radar of big politics, implying it’s subsumed. No evidence strongly refutes H3; none shows Faroes already singled out by Trump or the U.S. Weighing it, H3 appears true for the current state. However, H3 and H2 are somewhat overlapping: both essentially say Faroes haven’t been overtly targeted but are wrapped in the general approach. The difference: H3 emphasizes not yet singled out, which is accurate up to 2026. Therefore, we give H3 a high confidence (~85%) for the present situation. It might evolve, but all current indicators show Faroes talk is still packaged within Greenland/Danish context internationally.

The Faroes as a future pressure node once Greenland discourse normalized is more forward-looking and thus harder to “prove” with current evidence – but we do see several supporting pieces. E2, E8, E6 collectively indicate the Overton Window shift: once taking allied land is normalized (Greenland case), it paves way for new targets. E4, E5, E10 hint that competition is heating around Faroes (military visits, radar, Chinese interest), which could lead to direct pressure down the line. No evidence outright falsifies H4, since it’s about the future – one could only refute it if, say, Trump explicitly disavowed interest in Faroes (which he hasn’t; he’s just silent). The evidence suggests that if Trump (or a successor with similar views) succeeds partially in Greenland (even just normalizing the conversation), the Faroes logically could be next – especially as the Arctic focus intensifies. On ACH balance, H4 gets several pluses and no minuses, aside from being speculative. We assign Moderate confidence (~60%) to H4 – it’s plausible, perhaps even likely in a scenario where Trumpism in foreign policy persists, but not certain. It remains a contingent hypothesis: its realization depends on whether Greenland indeed “normalizes” U.S. assertiveness (which, by 2026, it sadly has to a degree) and whether strategic appetite extends to smaller fish like Faroes.

Probability Estimates: Summarizing in plain terms:

This ACH exercise underscores a key analytical point: the most confident conclusions are that Trump did not explicitly target the Faroes, but his Greenland and Arctic policies nonetheless put the Faroes in greater strategic peril indirectly. The Faroes remain, for now, somewhat in the diplomatic shadows (H3), yet everything Trump set in motion (H2) is moving them toward the spotlight (potentially H4 in coming years).

We should also grade our source reliability: The majority of evidence came from Category 1 or 2 sources: official statements, top-tier media (Reuters, AP, Guardian), and respected regional outlets (High North News, ArcticToday). These are generally reliable (A or B on typical scales) and credible – they reported verifiable facts (e.g., actual quotes, actual ship visits). A few items like behind-the-scenes reasoning (e.g. why Trump stayed silent) are analytical in nature or from commentary (C credibility). We flagged those as speculative.

No contradictory evidence was found that, say, Trump had a hidden Faroe plan. So our hypotheses weren’t in conflict with any discovered data. The main analytical uncertainty is projecting the future (H4) – which we appropriately hedge with probability and conditionals. We also acknowledge possible intel gaps: e.g. private communications between U.S. and Denmark about Faroes (we have none disclosed), or Faroese internal debates not public. If future disclosures show, for example, that Trump in 2019 asked his staff “Do we want the Faroes too?” (purely hypothetical), that would revise H1. Lacking that, we go with what we have.

In intelligence terms, we present our conclusions with probabilistic language, not absolutes, given the mix of confirmed info and interpretation. This ensures transparency about what is known versus inferred.

Having tested the hypotheses, we proceed to a holistic Risk Assessment & Strategic Outlook, integrating these findings to forecast near-, mid-, and long-term scenarios for the Faroes, and concluding with an analytic confidence statement and any caveats. <br>

With the evidence and hypotheses weighed, we now assess the risks to the Faroe Islands’ sovereignty and strategic status over three time horizons, and consider second/third-order effects. The analysis is informed by the structured techniques above and adopts a probabilistic confidence approach.

In the immediate future, a direct U.S. challenge to Faroese sovereignty remains unlikely (low probability). The Trump-era Greenland saga is still playing out; Washington’s bandwidth is consumed by that confrontation and its fallout. Allies have drawn a line that any attack on Danish territory (Greenland/Faroes) is intolerable. It’s improbable that even a brash Trump administration would open a “second front” by explicitly pressuring the Faroes while the Greenland issue is hot – it would unite Europe even more firmly against the U.S. (as we saw in 2026). Therefore, outright U.S. attempts to “buy” or claim the Faroes in the near term are very low likelihood (estimated <5%). Our confidence in this is high because it’s grounded in observed caution: Trump didn’t mention the Faroes when he easily could have, implying they weren’t an urgent target.

However, sovereignty risk by subtler means is present even near-term. We anticipate increased U.S. strategic courting of the Faroes: more visits, maybe joint initiatives. The risk to Faroese sovereignty here is indirect – not an attempt to remove Danish control, but to shape Faroese choices to align with U.S. interests. For example, within 1–2 years, the U.S. might fund a Faroese Coast Guard capacity-building program or push for an MOU allowing U.S. forces rapid access to Faroese ports in contingencies. These would be framed as “security assistance” or cooperation, not annexation. Yet they effectively bind the Faroes closer to the U.S. orbit, potentially reducing Denmark’s say. Denmark would likely acquiesce to such measures if they don’t overtly infringe sovereignty, especially to mollify Washington (Overton Window effect: things once off-limits, like a quasi-base arrangement, might become thinkable).

The great-power competition dynamic will also intensify in the near term. We have high confidence (based on trend analysis) that Russia will probe and China will angle for influence in subtle ways around the Faroes. Russia, bogged down by NATO unity on Greenland, might test allied resolve elsewhere: we might see, for instance, a Russian spy trawler mapping undersea cables near the Faroes or a propaganda push claiming “Faroese oppose NATO radar.” This would heighten threat perceptions and justify further Western militarization of the area, ironically feeding into U.S. justification to be more present. China, meanwhile, could re-approach with an economic carrot: perhaps offering Faroese salmon farmers expanded access to Chinese markets or hinting at infrastructure investments (like 5G again, or green energy projects). The Faroese government, now firmly pro-West due to Ukraine war solidarity, will likely tread carefully – we judge with moderate confidence that they will align with Denmark/NATO on critical choices (they already signaled end of Russia fish deal and avoided Huawei). But economic needs can be persuasive; a recession or fishery collapse could tempt them to accept Chinese money, which would trigger U.S. counter-pressure. Thus in the near term, the Faroes are navigating a narrowing strait (pun intended) between benefactors – this carries a moderate sovereignty risk not of overt takeover but of creeping dependency on one side or another.

Indicators to watch in near-term were outlined in I&W. If we see one flashing (e.g. a U.S. consulate announcement), the risk assessment would escalate. Absent that, the most likely near-term outcome is a quiet continuation of the status quo plus: the Faroes will be increasingly integrated into NATO planning (radar operational, maybe a small NATO footprint during exercises), and the U.S. will quietly solidify ties (perhaps a follow-up to the 2020 partnership focusing on security). For the Faroese people, the tangible impact may be limited at first – some more foreign soldiers sighted, a bit more diplomatic attention – but the strategic trajectory is set.

In the medium term, the probability of the Faroe Islands becoming an explicit pressure point rises modestly. By this time, one of two broad contexts may prevail: (A) Trump or a like-minded leader could be in power in the U.S. with unfinished Arctic ambitions, or (B) a more traditional U.S. administration could be trying to repair alliances but still dealing with the strategic realities Trump’s era created.

In scenario (A), if Trump (or an acolyte) regains the presidency in January 2029 (for instance), and if the Greenland situation remains unresolved, he may escalate further. If Greenland’s leadership continues to resist U.S. control, a frustrated Washington might look for other pressure valves. The Faroes could become a target as a way to squeeze Denmark: for example, Trump 2.0 might say, “If Denmark won’t relent on Greenland, maybe we seek a long-term lease of the Faroes for a U.S. base.” It sounds extreme, but mid-term Overton dynamics could make it conceivable – recall that by 2025, talk of using force on Greenland was no longer unthinkable. Under this adversarial scenario, we assign perhaps a 30% probability (low but not negligible) that the U.S. would try a direct gambit involving the Faroes (lease, purchase offer, basing demand). The fallout would depend on Europe’s stance – likely fierce opposition again. However, if NATO by then is weakened (imagine a scenario where Trump withdrew or undercut NATO severely in his second term), the calculus changes dramatically: the Faroes without NATO’s shield and with a diminished Denmark could be nearly defenseless against U.S. coercion. That is a worst-case mid-term risk: a unraveling of Western alliance frameworks leaving the Faroes isolated in negotiating with superpowers. Confidence in such a dire scenario is low (it requires multiple things to break bad), but it’s in the realm of possibility given recent fragility.

In scenario (B), a friendlier U.S. administration by late 2020s might not pressure overtly, but the strategic interest in the Faroes will remain high because of Russia and China. The Faroes could then face pressure in the sense of becoming heavily militarized as part of NATO’s deterrence. For instance, mid-term we may see semi-permanent rotational NATO forces in the Faroes – a company of Marines training annually, or an allied radar crew. While consensual, this could provoke Russia to explicitly threaten the Faroes as a target in wartime (“if NATO uses Faroes for military ops, they become a legitimate target”). Already in 2023, Russian military spokespeople hinted that “new NATO assets in the Arctic would be targets in conflict.” The Faroes, by 2030, may unfortunately earn that status. This is a different kind of sovereignty risk: not losing sovereignty in peacetime, but potentially losing security in wartime. It’s reminiscent of Cold War tripwire states (e.g. West Berlin). The Faroese might then begin debating neutrality – could they declare the islands a neutral zone (like Svalbard’s treaty status) to avoid being a battleground? Pushing for neutrality would conflict with being part of Denmark/NATO, raising complex legal issues. Mid-term, I’d put moderate probability on Faroese domestic debate intensifying on questions like “Do we want all this NATO presence? Are we safer or more at risk?”

We also consider Greenland’s trajectory mid-term: Greenland might by 2030 be edging toward an independence referendum. If Greenland votes to leave the Kingdom (even if under friendly terms), that leaves the Faroes as the last North Atlantic possession of Denmark. Danish resolve to keep the Faroes would be immense (losing both would be a national identity blow). But if Greenland goes, the U.S. might be less constrained about the Faroes – because Denmark’s geopolitical relevance would shrink, possibly reducing U.S. concern for Danish feelings. Conversely, Denmark might double-down on integrating the Faroes, offering them even more autonomy but within the kingdom, to prevent secession. I assess a significant mid-term risk that the Faroes will face a crossroads: either move toward independence (following Greenland’s example) or affirm union with Denmark under updated terms. Both paths carry external implications: independence = vulnerability to influence, while staying = target as part of Denmark. Either way, the U.S. and others will be paying close attention and possibly meddling quietly (e.g., a future U.S. administration might prefer an independent Faroes if it meant easier bilateral defense agreements; Russia might prefer an independent Faroes if it meant one less NATO territory).

Structural factors suggest that unless a major course correction occurs, the Faroe Islands are on a path to increased strategic risk in the long run. Climate change will continue to open Arctic waters; by the 2030s, trans-polar shipping and resource access will be more viable. The Faroes will then sit not just on a sub route, but potentially on a commercial sea lane between Europe and Asia (via Arctic). This raises their strategic value to all powers as a logistics and surveillance node. Great-power competition in the North Atlantic–Arctic corridor is likely to intensify, not diminish, given Russia’s unabated military programs (new submarines, etc.) and China’s growing global reach (maybe a presence in Iceland or a friendly Greenland). In such an environment, the Faroes could become akin to how Cold War Berlin or Cuba were – small places with outsized symbolic and strategic heft where powers test each other’s resolve.

In a pessimistic long-term scenario, if Trump’s brand of “might makes right” persists and perhaps is emulated by others (Overton Window permanently shifted), one could foresee a 2030s where territorial swaps or seizures are back on the table globally. That could imperil the Faroes’ very status. For instance, a desperate Denmark (if Greenland left) might be economically weaker; could the U.S. or UK offer financial incentives to effectively take over Faroese defense (a quasi-sovereignty)? Unlikely among NATO allies in normal circumstances, but after a decade of Trumpism, norms might erode to where even NATO’s existence is shaky. We must flag this as a low-probability but high-impact risk: a scenario where the Faroe Islands’ sovereignty is directly contested (whether by U.S., or conceivably by Russia in a conflict grabbing them as a forward post – the latter is very low probability but not zero if NATO collapsed).

In a more optimistic long-term scenario, lessons will have been learned from the Trump shock. The Overton Window could shift back somewhat – perhaps new international agreements reinforcing sovereign integrity in the Arctic (one could imagine a treaty or UN resolution explicitly forbidding purchase/forceful annexation of Arctic territories, to deter any repeats of the Greenland saga). If Western allies manage to fully mend fences and reaffirm principles, the Faroes might benefit from a stable status quo. Denmark could modernize the realm structure to give Faroes more agency without independence, removing grievances that external actors exploit. The U.S. might adopt a steadier Arctic policy that sees the Faroes simply as a partner, not a target. We assign maybe a 40% probability to this benign scenario – it’s feasible if leadership changes and global politics stabilize. However, given broader trends (great-power rivalry likely to endure), we lean slightly toward a more contested outlook.

Regardless of scenario, any U.S. pressure or increased presence in the Faroes will have ripple effects. It could cause domestic polarization in the Faroes (independence hardliners vs. pro-Danish unionists vs. those aligned with foreign patrons). It could impact Faroese economy – for example, if the islands become seen as a military outpost, tourism (a growing sector pre-COVID) might decline, or conversely, military spending could boost local income. Regionally, how the Faroes are handled will affect Iceland and Norway’s calculations too. They share the GIUK environment; if the U.S. overreaches in Faroes, Iceland may worry it’s next (though independent, Iceland might fear being strong-armed on base issues again). So the Faroes could become a bellwether for small-state agency in the High North. Allied nations like Canada will watch closely – Canada’s own Arctic sovereignty battles mean they’ll likely back Denmark/Faroes staunchly (we saw Canada’s support on Greenland, and presumably would extend to Faroes if push came to shove).

We present these assessments with moderate overall confidence. The short-term and current-state judgments (H2, H3 being true; no immediate direct U.S. threat) are made with high confidence due to solid evidence. Predictions into mid and long term are necessarily lower confidence, as many variables can change (political leadership, war or peace, independence movements). Key intelligence gaps include internal U.S. planning (we do not know if contingency plans for Faroes exist), and the private intentions of Faroese and Danish leaders (will the Faroes seek a referendum eventually? They’ve been coy publicly). Also, the health of NATO post-Trump is a wildcard – our risk assessment assumes NATO mostly holds, but if that gap in our assumption is wrong, risks escalate beyond what we’ve outlined.

Our OSINT-based approach relies on public sources up to Jan 2026. If classified negotiations or understandings exist (for example, maybe Denmark quietly got U.S. assurance not to touch Faroes in exchange for radar – purely hypothetical), we wouldn’t know. Such hidden factors could mitigate or exacerbate risk unseen. We also assume rational behavior to a degree – e.g., that Trump wouldn’t fight on two fronts (Greenland & Faroes) simultaneously because it’s counterproductive. Given Trump’s unpredictable style, rationality is not guaranteed; thus, an out-of-the-blue Faroes incident can’t be entirely ruled out even sooner. This is a low-likelihood black swan.

In closing, our assessment is that the Faroe Islands, once an obscure corner of NATO, have been pulled into the limelight of Arctic great-power politics by the cascade of events unleashed during Trump’s tenure. Documented intent by Trump toward the Faroes is nil – but implicit strategic intent is evident in the pattern of U.S. actions and rhetoric. The Faroes’ sovereignty is not under imminent direct threat, yet the risk environment around them has deteriorated. Their best defense remains the strength of Western alliances and the rule of law – both of which have been stressed but not broken. Policymakers and analysts should heed the indicators outlined: they will be the early warning sirens if what was once unthinkable – a tug-of-war over the Faroes – ever starts to materialize. For now, the Faroese can continue their lives of fishing and fjords in peace, but with one eye on the horizon where foreign ships gather and one ear listening for the distant rumble of global powers converging on their waters. <br>

In a speculative thriller, the Faroe Islands might next become the object of a Trumpian “art of the deal.” In reality, our investigation finds no explicit evidence that Donald Trump ever set his sights on the Faroes the way he did on Greenland. Documented intent toward the Faroes is absent; Trump’s Arctic obsession fixated on Greenland as the jewel in the crown. However, implicit signaling and second-order effects have inexorably pulled the Faroes into the strategic vortex created by Trump-era geopolitics. The **renewed U.S. posture toward Greenland – from musings of purchase to threats of forcible takeover – and the abrasive questioning of Canada’s Arctic sovereignty cracked the once-firm bedrock of allied territorial integrity. Through that crack glints the Faroes’ predicament.

Our analysis concludes that Trump’s actions materially increased the Faroes’ exposure to great-power maneuvering (High confidence). While not (yet) singled out by name (High confidence), the Faroes have become a piece on the Arctic chessboard by implication. We find it plausible that the Faroes could become a direct pressure node in the future (Moderate confidence) if the patterns observed continue. Each hypothesis was evaluated with source-based evidence and structured techniques, and none were taken as gospel without corroboration.

We express our judgments with appropriate confidence levels: high confidence that Trump did not deliberately target the Faroes, high confidence that U.S. strategic interest grew around them anyway, and moderate confidence in projections of future risk. These confidence levels reflect the quality of evidence (strong for past events, weaker for future intent) and acknowledge intelligence gaps. Notably, we lack inside information on Trump’s private deliberations or any current U.S. contingency plans for the Faroes. The credibility of sources used is generally high – official statements, reputable journalism, and think-tank analyses form our evidentiary backbone. Where we ventured into extrapolation, we labeled it as such (e.g., Overton Window analysis, speculative extrapolation under H4) to distinguish it from documented fact.