Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

The Indian Air Force (IAF) and the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) are two of the largest and most capable air arms in South Asia. By 2025, both forces have undergone modernization since their last major clash in 2019, upgrading fleets and improving support systems. This report provides a holistic comparison of the IAF and PAF across multiple dimensions: current combat and support aircraft inventories, training quality and operational readiness, doctrinal differences, air defense and drone capabilities, force multipliers (like AWACS and tankers), and industrial/logistical capacity. It also examines the impact on air power balance of their recent engagement in May 2025, during Operation Sindoor, in which the IAF reportedly lost five aircraft, and discusses likely Pakistani response strategies in its aftermath.

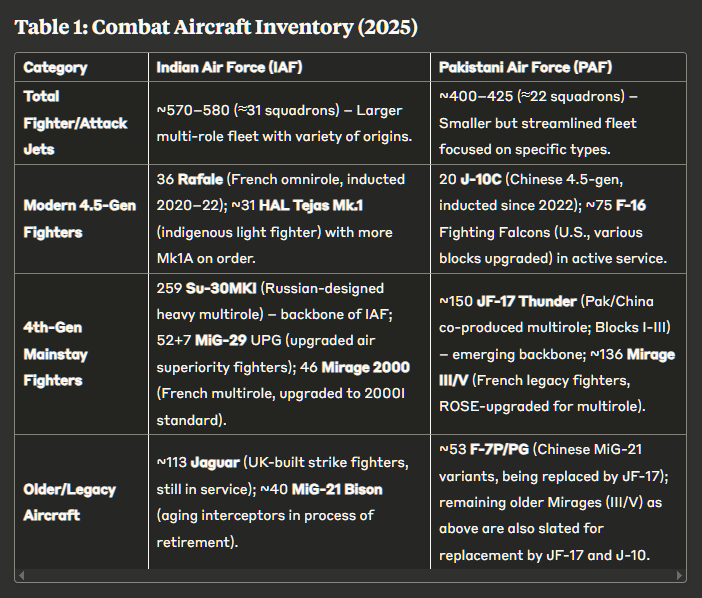

The IAF is substantially larger, with roughly 570–580 combat-capable aircraft (organized into 31 fighter squadrons as of early 2025), whereas the PAF fields around 400–425 combat aircraft (~22 squadrons). The IAF’s inventory is diverse, featuring Russian, Western, and indigenous jets, while the PAF’s fleet is a mix of U.S., French, Chinese, and co-produced aircraft. Table 1 summarizes the combat aircraft holdings of each air force:

India’s fleet is numerically larger and more varied, including heavy twin-engine fighters (Su-30MKI), Western platforms (Rafale, Mirage 2000, Jaguars), and indigenous jets (Tejas). Pakistan’s smaller fleet has been modernizing with high-tech additions to offset quantity gaps – for example, the induction of 36 IAF Rafales was countered by PAF acquiring at least 20 Chinese J-10CE fighters since 2022, which Pakistan sees as a rough equivalent in capability. Both Rafale and J-10 carry advanced long-range air-to-air missiles (IAF’s Meteor vs PAF’s PL-15) that far exceed the ranges seen in the 2019 skirmishes. The PAF also relies on ~75 F-16s (upgraded older models and newer Block-52s) as a high-end cornerstone. Meanwhile, the IAF’s workhorse Su-30MKIs (over 250 in service) give it a qualitative edge in range and payload, and India continues to upgrade these with modern avionics and sensors to keep them effective through the 2020s. Both air forces are phasing out 1960s-era designs (MiG-21 in IAF; F-7/Mirage III in PAF) in favor of these newer platforms.

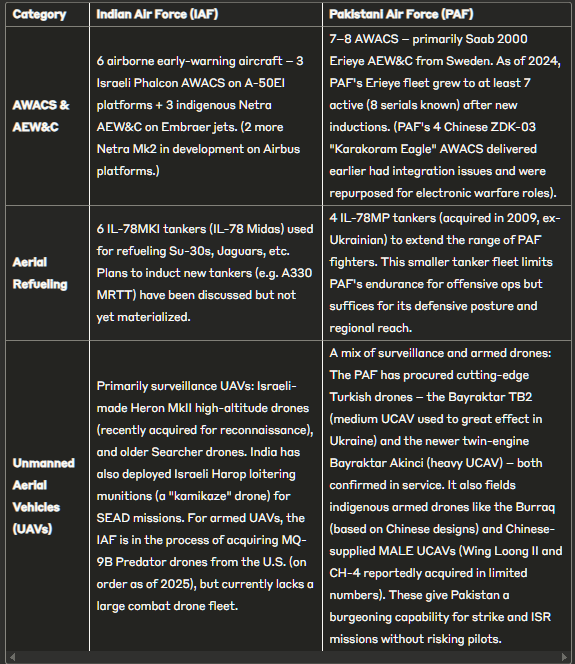

In terms of force multipliers and support assets, both forces have been investing in airborne early-warning and control (AWACS) aircraft, tankers, and intelligence platforms, though the scales differ (see Table 2):

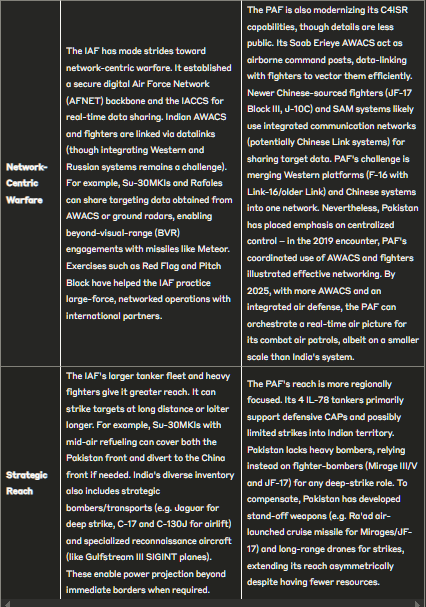

Overall, the IAF enjoys a numerical and technological edge in most categories – more fighters (including high-end jets like Su-30MKI and Rafale), more tankers, and a broader array of indigenous and imported systems. The PAF, however, has sharply focused its modernization on force multipliers and quality improvements to narrow the gap. Notably, Pakistan’s fleet of AEW&C aircraft is now comparable in size (if not larger) than India’s, with at least 7 Saab Erieye in service (vs. 5–6 AWACS for IAF). This parity in “eyes in the sky” partly offsets India’s numerical superiority in fighters, as it improves Pakistan’s situational awareness and coordination. Both forces have enhanced their BVR combat capabilities since 2019 (with Meteor and Astra missiles for IAF, and PL-15 and upgraded AMRAAMs for PAF), making any future air engagement potentially fast and decisive at long ranges.

Both air forces maintain rigorous pilot training programs, but there are structural differences. The PAF historically has a higher pilot-to-aircraft ratio (~2.5 pilots per aircraft) compared to the IAF’s ~1.5 pilots per aircraft. This means Pakistan trains more pilots for a given number of jets, allowing it to generate more sorties per day in wartime by rotating crews. In a conflict, a single fighter can fly multiple missions, but human pilots have endurance limits – a sphere where PAF’s greater pilot reserve can be advantageous. Indeed, analysts note this could let the PAF conduct continuous day-night operations more efficiently than the IAF in a high-tempo short war.

The IAF, for its part, has been addressing training shortfalls by increasing simulation and international exercises. Indian pilots routinely participate in drills like the U.S. Red Flag, Australia’s Pitch Black, France’s Garuda and other bilateral exercises. These give IAF aircrew exposure to diverse tactics and high-end combat scenarios against Western air forces. The IAF’s elite pilots undergo training at institutions such as TACDE (Tactics and Air Combat Development Establishment), akin to a Top Gun school for honing dogfighting and mission planning skills. PAF pilots train at the Combat Commanders School (CCS) which plays a similar role, refining combat tactics and air combat maneuvers.

Western assessments generally consider PAF pilot training to be highly professional and on par with top air forces, given Pakistan’s focus on quality to offset quantity disadvantages. The PAF’s training benefited from decades of U.S. cooperation (in the Cold War era) and, more recently, close coordination with China and Turkey. Pakistani pilots have proven adaptable – for instance, they transitioned from flying older Mirage/F-7 to modern JF-17 and J-10 with relative ease in recent years. The IAF also has highly skilled pilots; in past international exercises, IAF pilots in Sukhoi-30MKIs performed impressively against NATO aircrews. However, the IAF has faced issues like fewer flying hours per pilot in some squadrons due to budget and maintenance constraints, and an over-reliance on simulators for certain weapons training. These issues are being mitigated as serviceability of aircraft improves and new trainers (like the Hawk AJT and upcoming LCA trainer variants) enter service.

On any given day, the IAF’s sheer size means a larger absolute number of aircraft are mission-ready, but in percentage terms the PAF may achieve a higher availability rate. India’s fighter fleet includes many older jets (e.g. Jaguars, MiG-21) that are maintenance-intensive and slated for retirement, which can drag down overall readiness. The Su-30MKI fleet, while formidable, in the past suffered 50–60% availability due to spare parts issues; this has improved to around 70% after HAL (Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd) established local supply of spares and overhauls. The IAF has also been procuring additional stocks of Russian engines and components (e.g. a 2024 order for 240 new AL-31FP engines for Su-30s) to ensure fleet sustainmentd. Pakistan’s maintenance crews are highly trained and have kept vintage aircraft like Mirages flying for decades with upgrades (Project ROSE) and by sourcing spares globally. The Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC) at Kamra provides in-country overhaul for assets like the JF-17, Mirage III/V and even C-130 transports. Still, PAF readiness could be impacted by sanctions or parts availability for its U.S.-made jets – a constraint partly alleviated by a 2022 U.S. sustainment package of $450 million to support Pakistan’s F-16 fleet.

The strategic doctrines of the two air forces are shaped by their threat perceptions. The IAF’s doctrine is influenced by the possibility of a two-front war (against Pakistan in the west and China in the north/east). Thus, India emphasizes multi-role aircraft that can be re-deployed between fronts, and seeks numerical superiority (a government target of 42 squadrons by 2035, though reaching this has been delayed). The IAF doctrine calls for air dominance early in a conflict, using offensive counter-air strikes to cripple enemy air bases and gaining control of the air to support Indian ground forces. India has invested in stand-off precision weapons (e.g. Spice-2000 guided bombs, BrahMos cruise missiles) to strike high-value targets across the border without exposing aircraft to enemy air defenses. The 2019 Balakot strike exemplified this approach: IAF Mirage 2000s dropped precision bombs on a target in Pakistan while staying within Indian airspace, relying on stand-off range. The lesson from that for India was to further enhance long-range strike and all-weather, day-night capabilities. India is likely to make use of an even more aggressive and entrenched position, a trend consistent with Prime Minister Modi’s increasingly centralized, populist command style, where escalation dominance is viewed as a political asset rather than a strategic liability.

Pakistan’s air doctrine, on the other hand, is shaped by a need to protect its airspace against a larger adversary and to retaliate in a manner that deters further aggression. Given its fewer assets, the PAF has a doctrine of high readiness and quick response – often termed “offensive-defense.” This means the PAF trains to seize the initiative early in a conflict or crisis despite being defensive overall. A historical precedent was in 1965 and 1971 wars when Pakistan launched pre-emptive strikes on IAF bases. In modern context, Pakistan demonstrated its doctrine in the February 2019 episode: the day after India’s Balakot strike, the PAF launched Operation Swift Retort, a retaliatory daylight airstrike at Indian military installations in Kashmir, deliberately calibrating the impact (hitting open areas near targets) to send a message without pushing India into full war. During that operation, PAF fighters (including F-16s and JF-17s) engaged intruding IAF jets and shot down an Indian MiG-21, showcasing Pakistan’s ability to respond swiftly and in a coordinated fashion. This approach – rapid, limited, and well-publicized response – is likely to be the PAF’s doctrinal template to retaliate against any future Indian strikes, as it aims to deter escalation by proving it can exact a cost.

Another doctrinal element for Pakistan is its integration of conventional air operations with its nuclear posture. PAF aircraft (e.g. dual-capable F-16s or Mirage III with Ra’ad cruise missiles) are part of Pakistan’s nuclear second-strike capability. This acts as a backdrop to any all-out conflict: the PAF’s doctrine does not seek deep penetration into Indian territory (which could be escalatory), but rather to deny India air superiority over Pakistan and keep open the option of last-resort nuclear response if Pakistani sovereignty is threatened. The IAF also fields nuclear-capable aircraft (Mirage 2000, Jaguar and potentially Rafale with nuclear BrahMos variant or gravity bombs), but India’s doctrine emphasizes a strict separation of conventional and nuclear spheres, with a No-First-Use policy. Thus, conventionally, the IAF can plan for large-scale strikes without nuclear considerations in the foreground, whereas the PAF’s planning is somewhat intertwined with Pakistan’s overall deterrence strategy.

Culturally, the two air forces have mutual respect but also carry the legacy of past encounters. Pakistani fighter pilots historically earned a reputation for professionalism and aggressiveness, claiming favorable kill ratios in earlier wars (contested by India). The IAF’s larger organization has had to work harder to maintain a high standard across a big force, whereas the smaller PAF is often described as an “elite club” with a tight-knit cadre of pilots. Both forces have been upgrading their training infrastructure: India with new simulators, an Aerospace Medicine institute for high-altitude flying, and more frequent joint exercises; Pakistan with collaborations with the Chinese PLAAF in Shaheen exercises and with Turkey and other allies, giving PAF pilots DACT (dissimilar air combat training) opportunities against foreign aircraft. In summary, training and readiness are strong in both, but Pakistan’s approach is to maximize per-aircraft effectiveness, while India’s is to leverage mass and diversity – a reflection of their doctrines and force structures.

Both nations have significantly enhanced their ground-based air defense and unmanned aerial capabilities in recent years, seeing them as critical force multipliers and asymmetrical tools to gain advantage.

India’s procurement of the S-400 system from Russia is a game-changer for its air defense. The IAF has begun deploying S-400 batteries to cover both the western (Pakistan) and northern (China) sectors. With an array of interceptors (40 km, 120 km, 250 km ranges), the S-400 provides a layered defense by itself and can target adversary aircraft long before they approach Indian airspace. This creates a dilemma for the PAF, as any large formations or high-value assets (like AWACS or tankers) would be at risk if they operate too close to the border during hostilities. To cover gaps below the S-400’s umbrella, the IAF/Indian Army deploy the Akash medium-range SAM (which has been upgraded to Akash-NG) and the Barak-8 MR-SAM (a joint development with Israel, effective up to ~70 km). At lower altitudes, quick-reaction SAMs like Spyder (Israel) and indigenous QRSAM (in trials) protect bases and point targets. India’s radar network is extensive, including the Integrated Air Command and Control System (IACCS) nodes which fuse data from dozens of radars (like the Indra, Rohini, and Green Pine/Arrow systems acquired from Israel). This integrated picture is shared with fighter squadrons and SAM batteries, enabling a coordinated response to intrusions.

Pakistan, recognizing its traditional weakness in ground-based air defense, made major new acquisitions post-2019. It turned to China and acquired high-end SAM systems to create its own multi-layered shield. The HQ-9BE long-range SAM, revealed in PAF service, reportedly can engage targets out to 200+ km, which, while slightly inferior to S-400, still provides Pakistan with beyond-visual-range engagement capability against enemy aircraft. The fact that the HQ-9 is based on the HQ-9/P variant operated by the Pakistan Army (with ~125 km range) means both Army and PAF now operate similar long-range systems, improving redundancy. The induction of HQ-16FE/LY-80 systems (with ranges of 40–70 km for earlier versions, and up to 150 km for the extended range versions) fills the medium-tier, roughly analogous to India’s Akash/Barak-8 in role. Short-range defenses include the Chinese FM-90 (improved Crotale) and guns like Skyguard and Rheinmetall 35mm twin AA. By 2025, Pakistan’s integrated air defense comprises overlapping coverage: very long range HQ-9BE, long/medium HQ-16 and HQ-9P/FD-2000, and point defenses – all cued by an improved radar network. This is a significant shift from 2010, when Pakistan relied mostly on fighter intercepts for air defense; now SAMs can take a larger role, as seen globally (the Russia-Ukraine war underscored how modern SAMs can even deny advanced fighters and missiles).

The use of drones has rapidly expanded in South Asia’s security calculations. Drones provide surveillance, target acquisition, and even strike options without risking pilots, and both IAF and PAF have developed these capabilities, albeit in different ways.

The rapid enhancement of SAM networks by both countries makes their airspaces more contested. In a war, the IAF cannot take air superiority for granted despite its larger air force – it would first have to degrade Pakistan’s SAMs (possibly using anti-radiation missiles, Harop drones, or even ground forces) to safely employ its numerical advantage. Conversely, the PAF will find it challenging to penetrate Indian air defenses; any deep strike mission would require suppressing the S-400 and other layers, which Pakistan might attempt with barrages of cruise missiles or swarm drone attacks. This cat-and-mouse of offense-defense has sharpened since 2019, essentially creating a stand-off where outright attacks are riskier. Drones somewhat upset this balance by being harder to detect on radar and more expendable – expect both sides to use UAVs to probe and weaken enemy defenses early in a conflict.

Sustaining high-intensity air operations requires a robust industrial base and logistics pipeline for spares, repairs, and replacements. Here, India’s larger economy and more developed defense industry provide it a long-term advantage, though not without issues, while Pakistan leverages alliances (mainly with China, and to some extent Turkey and the US) to keep its air force running.

India has a decades-old aerospace industry centered around Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL). HAL has license-produced hundreds of aircraft like MiG-21s, Jaguars, Su-30MKIs and Hawk trainers over the years, and is now manufacturing the indigenous Tejas fighter. By 2025, HAL’s Nasik plant has not only built the existing Su-30MKI fleet under license but also received a new order to produce 12 more Su-30MKIs (to replace attrition losses) with higher indigenous content. HAL is also contracted to deliver 83 Tejas Mk1A between 2024–28, which will gradually improve squadron strength. This local production capability means that in a prolonged conflict or arms race, India can domestically manufacture certain fighters and key parts (for instance, HAL’s Koraput division makes the AL-31FP engines with over 50% local content). Additionally, India’s private sector is increasingly involved – e.g. Tata and Boeing’s joint venture producing fuselages for Apache helicopters, and likely involvement in any future MRFA (Medium fighter) program. The presence of domestic overhaul facilities (for MiG-29, Su-30, Mirage 2000, etc.) allows the IAF to repair battle-damaged aircraft or wear-and-tear from sustained ops relatively quickly without needing to send them abroad.

Pakistan’s domestic aviation industry is smaller but has made notable strides, particularly through Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC) at Kamra. PAC, in collaboration with China’s AVIC, co-produces the JF-17 Thunder – a true joint fighter production program. By 2025, Pakistan has produced over 100 JF-17s locally (including dual-seat JF-17B), with a steady production line that can deliver a few units per year. However, the JF-17 still relies on foreign components (notably the Russian RD-93 engines and Chinese avionics), so sustained output would depend on continued Chinese and Russian supply. PAC Kamra also undertakes rebuild/overhaul of aircraft like the Mirage III/V and C-130, extending their service life. In terms of munitions, Pakistan has developed some indigenous weapons (e.g. the H-4 glide bomb, Barq missile for drones, etc.), but still imports most advanced missiles (AMRAAMs from the US, PL-series from China). One limiting factor for Pakistan is its economic situation – high-intensity operations would consume expensive munitions (BVR missiles, guided bombs) that Pakistan’s defense budget might struggle to replace quickly. During peacetime, Pakistan has managed to stockpile a decent arsenal with Chinese help; for example, the PL-15 long-range AAM is now equipping JF-17 Block III and J-10C, providing parity with India’s Meteor missile.

The IAF’s logistics benefit from diversified suppliers but also suffer from complexity. India operates Russian, French, British, Israeli, and now American (C-17, Chinook) aircraft – a maintenance nightmare in some respects. Each supply chain (Russian vs Western) has its own timelines. India has mitigated this by signing logistics agreements (like spares support pacts) and emergency purchase agreements. For example, after the 2019 clash, India expedited purchase of more air-to-air missiles from Russi and Israel. For a sustained war, India’s large war reserve stocks (e.g. strategic reserves of missiles, fuel) and the ability to purchase more from multiple markets (Russia, Israel, France, US) give it resilience. Domestically, ordnance factories produce large quantities of unguided bombs, rockets, and some missile components. One challenge for India is serviceability of older fleets – e.g. the Jaguar’s British engines are long out of production, and MiG-21s are basically at end of life, so keeping those flying in a war would be tough. But those are slated for retirement anyway.

Pakistan’s logistics are leaner and somewhat dependent on foreign goodwill. The F-16 fleet, for instance, relies on the U.S. for spares and support. In 2019, there were concerns that Pakistan’s use of F-16s against India might jeopardize future support due to end-use restrictions. The Biden administration’s approval of a $450 million sustainment program in 2022 alleviated some of that concern, ensuring Pakistan’s F-16s get necessary maintenance and upgrades. For Chinese-supplied equipment, Pakistan benefits from China’s extensive inventory – e.g. PLAAF also uses J-10 and similar SAMs, so ammunition and spare parts could be readily provided by China even during a conflict (especially since China is a strategic ally of Pakistan). China’s political backing effectively guarantees a supply line for munitions like the PL-15 missiles or spare parts for JF-17s, unless China itself is involved in conflict with India. Pakistan has also localized maintenance for Chinese gear to an extent (for example, building a factory to produce UAVs and assembling VT-4 tanks, etc., showing a general trend of tech transfer).

In terms of sustained operations, analysts often note that while India and Pakistan might be closely matched in an initial exchange, India’s greater resources would come into play over a longer period. India’s larger economy (roughly 10 times Pakistan’s GDP) means it can ramp up war production, spend more on imports, and absorb losses more easily in a prolonged war of attrition. Pakistan’s strategy would likely be to avoid a long war and instead aim for a short, sharp conflict where its ready forces can be decisive before war economics become critical. Both air forces have limited stocks of their most advanced weapons (for example, India reportedly has limited Meteor missiles and Pakistan limited PL-15s due to high cost per unit), so a swift conflict might see most of these used up in days. After that, whichever side can rearm faster would have the edge – a race that favors India due to its international partnerships and production base.

Infrastructure and Basing: Logistics also ties into how many bases and dispersion options each side has. The IAF has a broad network of airbases spread across its vast territory, with depth airfields in western India that are out of range of most PAF strikes. It also has hardened shelters and duplicate runways at frontline bases. India has been upgrading runways and facilities in the border areas (including highway landing strips) to ensure resilience. Pakistan, being geographically narrower, has fewer airbases, and most are within a few hundred kilometers of the border. The PAF has mitigated this by building extensive hardened aircraft shelters (HAS) and by training for rapid dispersal of aircraft to secondary airfields or road bases in wartime. During high tensions, PAF often disperses fighters to highways or smaller airstrips to complicate IAF targeting. Pakistan also has an early warning organization (Supplementary radar and observers) to give maximum notice of incoming Indian attacks, so that its aircraft can “scramble and scatter” if needed. However, Pakistan’s internal lines are short – which is an advantage for turnaround time (an aircraft can take off, engage, land back for rearm within a short cycle). India’s bases, being farther, mean longer transit times for CAP missions, etc., unless they forward deploy closer (which then become potential targets). In logistics terms, Pakistan can refuel and rearm faster due to proximity to the fight, but India can rotate squadrons from other regions if a particular sector’s units get exhausted.

In summary, India’s industrial and logistical capacity gives it a sustainability edge – if a conflict drags on, the IAF can keep fighting longer with fresh equipment and replacements. Pakistan’s capacity is more limited, so the PAF would aim to husband its resources and fight smart to force a quick resolution. Both sides know this, which influences their strategies (Pakistan would seek external diplomatic intervention before its stocks run low; India might seek to stretch Pakistan’s endurance). The events of May 2025 would put some of these assumptions to the test.

In early May 2025, a significant air engagement took place between India and Pakistan, marking the most serious aerial clash since 2019, when India launched Operation Sindoor, and sustained a loss of five airframes while Pakistan lost none. While details are still emerging, this loss of multiple IAF aircraft in one encounter has notable implications for both the balance of power and the strategies going forward. It also demonstrates the likely current superiority of the Pakistani Air Force.

The skirmish was a large-scale exchange involving advanced jets and air defenses on both sides. Reports suggest the losses on the IAF side included a mix of aircraft – possibly two French front-line fighters and three additional fighters shot down in air-to-air combat or lost to ground-based air defenses or accidents in the fray. It appears that all of Pakistani’s kills took place from standoff distance, and this demonstrates a significant lack of maturity on the part of the IAF. Regardless of the exact breakdown, losing five airframes in a single day is a steep cost for the IAF. To put this in perspective, India in past conflicts (1965, 1971, even Kargil 1999) rarely saw so many aircraft lost in one day of fighting; even in February 2019, it definitively lost two aircraft (a MiG-21 in combat and an Mi-17 helicopter to friendly fire) in the worst day. Therefore, five in one engagement reflects serious operational failures or doctrinal missteps on the part of the Indian Air Force.

For the IAF, these losses immediately reduce its available strength in the short term. At roughly 31 squadrons in early 2025, the IAF is already below its sanctioned strength, and every aircraft matters. If the lost airframes included modern ones like a Su-30MKI or Rafale, that would sting both in capability and morale – those jets are expensive and not quickly replaceable (India does have 12 new Su-30MKIs on order to offset attrition, but those deliveries will take time). The psychological impact on the IAF could be mixed: on one hand, such losses might necessitate more cautious tactics in subsequent missions; on the other, they could galvanize the force to tighten its procedures and seek retribution.

On the Pakistani side, if indeed PAF fighters and/or SAMs inflicted these losses, it would be hailed as a major success – a “Operation Swift Retort 2.0” on a larger scale. It would validate Pakistan’s investments in better training and BVR weapons. Notably, if a PAF JF-17 or J-10 shot down an IAF Su-30 or Rafale with a PL-15 missile, that would demonstrate the lethality of Chinese hardware against top-of-the-line Western/Russian jets, something that regional observers (and China) would note carefully. Likewise, if a new SAM like the HQ-9BE downed an Indian fighter, it proves the efficacy of Pakistan’s new air defense umbrella.

In the immediate aftermath, the IAF likely raised its alert status across all airbases. Combat air patrols would be intensified to prevent any further surprises. India may also choose to temporarily ground certain fleets for technical checks (for instance, ensuring there was no systemic issue if any crashes happened due to malfunction). Losing five jets might impel the IAF to request emergency force multipliers – e.g. asking friendly countries for fast-tracked delivery of spares or even leasing of aircraft (India in the past has discussed leasing fighters or tankers in emergencies). However, given the short time frame, the IAF’s recourse is to regroup and retaliate with what it has, to re-establish deterrence.

From a force ratio perspective, a loss of five aircraft won’t cripple the IAF’s overall numerical edge. India still retains on the order of 550+ fighters versus Pakistan’s ~400. But in the localized theater of Kashmir/Punjab where the battle likely occurred, that engagement may have eroded a chunk of the available IAF sorties for the next day or two (until reinforcements are moved in). The IAF would also analyze whether those losses were due to any tactical mistakes – for example, did Indian pilots overcommit into Pakistani SAM engagement zones? Did PAF successfully lure IAF fighters into an ambush using AWACS guidance? These questions will shape India’s subsequent tactics.

Strategically, the engagement demonstrates that the PAF, though smaller, can hold its own and even impose losses on the larger IAF, especially on the defensive. This will likely inject a dose of confidence in Pakistan’s public and military, and conversely, be a wake-up call for India. The regional air power balance, which in raw numbers favors India, in practice can be balanced by smart tactics and technology – a fact underscored by this clash. If five Indian jets were downed without corresponding Pakistani losses (or with minimal losses), it tilts the immediate balance in Pakistan’s favor in the air. However, if a second round of conflict occurs, India might bring more of its weight to bear to redress that.

We must note that modern air warfare’s outcomes often hinge on enablers and context. India has more depth to absorb losses; for instance, even after losing five jets, the IAF could surge aircraft from other commands (say from the Central or Eastern Air Command) to the front-line Western Command. Pakistan, meanwhile, likely put its whole air force on high alert and maybe flew a large percentage of its fleet in that engagement. Sustaining such a tempo is challenging for the PAF beyond a few days. Thus, if the conflict were not immediately halted, the balance might swing back as India’s capacity to deploy fresh forces comes into play.

Given that this engagement was triggered by India’s Operation Sindoor, Pakistan’s immediate response has been the air battle itself – essentially a retaliation. Following this, what might the PAF (and Pakistani leadership) do next?

On the other side, the IAF and Indian establishment will be formulating their next steps. While the question focuses on Pakistani response, it’s worth noting that India’s likely reaction will influence Pakistan’s strategy. If India decides to retaliate massively (say with a coordinated strike on multiple PAF bases), Pakistan’s response would shift from poised defense to active offense to counter that strike. However, given both nuclear overhang and international pressure, India might opt for a tempered response – perhaps a limited missile strike on a Pakistani military installation at night, or an aerial engagement over the Line of Control under strict rules of engagement to avoid Pakistani airspace. Pakistan’s strategy would be to intercept and thwart any such Indian attempt, thereby repeating the narrative of “defender’s advantage.”

The loss of five Indian airframes, in the broader balance, slightly narrows the quantitative gap between the two air forces – especially because Pakistan has not lost a single jet as of the writing of this piece. If tensions subside after, India will undoubtedly fast-track acquisitions to replace those losses – for example, it might expedite the procurement of additional Rafales or even pull old jets out of storage to refill squadron numbers temporarily. Pakistan, for its part, will frame the engagement as proof that any future war will be costly for India despite its size. This could feed into Pakistani planning that offensive deterrence works – i.e., showing capability and will to shoot down Indian jets deters India from exercising its numerical advantage freely.

From a regional perspective, countries like China will study the results keenly. For China (which is allied with Pakistan and also faces off against India), the engagement offers a testing ground for Chinese weapons (PL-15 missiles, JF-17, J-10, HQ-9 SAM) against Indian and Western systems. A strong Pakistani showing implicitly advertises Chinese military tech’s effectiveness. This could influence the regional arms dynamic – for instance, India might feel compelled to acquire more Western systems (like additional Meteor missiles, or advanced EW suites) to counter the demonstrated Chinese tech.

Finally, the engagement underscores that despite India’s overall stronger air force, Pakistan retains considerable punch. The regional air power balance in South Asia is therefore not one-sided; it is a balance of quantity vs quality/concentration. The IAF has the challenge of covering two fronts and dispersing its focus, whereas the PAF can concentrate fully on the Indian threat. In the May 2025 battle, that concentration paid off for Pakistan. Moving forward, India may adapt by allocating more frontline squadrons to the Pakistan front or by improving jointness with its Army/Navy to deal with Pakistan swiftly while containing China. Pakistan will continue seeking force multipliers (possibly more drones or even procuring stealth aircraft in the future) to build on the success.

By 2025, the Indian Air Force and Pakistani Air Force have evolved into highly capable, yet differently oriented, forces. The IAF leverages its larger size, diverse fleet, and stronger industrial base to project power on two fronts and aims for technological superiority (as seen with Rafales, S-400s, and indigenous projects). The PAF, though smaller, has achieved a punching-above-its-weight status through focused upgrades, intensive training, and clever use of force multipliers like AWACS, high-end SAMs, and drones.

A direct comparison shows India enjoying a numerical edge in combat aircraft (roughly 1.5 times the size of PAF’s fleet) and a wider array of support assets, while Pakistan compensates with higher readiness and targeted acquisitions (e.g. matching India’s new capabilities with counter-capabilities – J-10 vs Rafale, HQ-9 vs S-400, etc.). Doctrinally, India’s approach is offensively oriented with an eye on long-term dominance, whereas Pakistan’s is defensively reactive with an emphasis on denying a quick Indian victory.

The recent May 2025 battle, with the IAF’s loss of five airframes, highlighted that quality and tactics can momentarily outweigh quantity. Pakistan’s ability to inflict losses on India has altered immediate perceptions of air superiority in the region. However, if conflict were to widen, India’s depth of resources and industrial stamina would start to tell. Both air forces are integrating new technologies – from network-centric warfare to drones – making any future conflict unprecedented in complexity and risk. The presence of nuclear weapons on both sides further raises the stakes, ensuring that even conventional air engagements are carefully calibrated.

In any future scenario, the outcome of IAF vs PAF engagements will hinge on who controls the skies (AWACS and electronic warfare will be decisive), how effectively each side neutralizes the other’s air defenses, and whether they can sustain operations after initial clashes. The events of 2025 may prompt the IAF to accelerate modernization (expediting programs like the Tejas Mk2 or MRFA for additional fighters) and improve pilot training ratios, while the PAF may seek to acquire force multipliers like aerial refueling from new sources or even stealth UCAVs to maintain its edge.

In summary, as of 2025 the IAF holds a broad advantage in scale and multi-front capability, but the PAF maintains a formidable and agile force that is highly effective in the Pakistan-India context. The loss of five IAF jets in combat serves as a cautionary tale that strength in numbers must be married with superior strategy and readiness – something both sides will undoubtedly take to heart. Continued modernization on both sides will keep a competitive balance, and any future conflict would likely be fast and intense, with the potential for rapid shifts in advantage. Thus, the air power balance in South Asia remains delicate, where even a single day’s clash can recalibrate perceptions and strategies on both sides of the border. Ultimately, and with Modi exacerbating and worsening the Indian-Pakistani Crisis, it is his decisions that are likely to determine whether or not the PAF will once again have the chance to challenge the IAF.

[…] up along several points of the LoC, sending Indian villagers scrambling for cover in bunkers. The Pakistani Air Force scrambled jets, and for a few tense hours both nations’ airspaces were alive with the high-octane […]