Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

The prospect of a peace agreement in Ukraine offers a moment of respite but does not resolve the deep structural tensions between NATO and Russia. If anything, it may simply shift the battlefield elsewhere. Over the past decade, NATO and Russia have engaged in an escalating security competition, with flashpoints across Eastern Europe, the Arctic, cyberspace, and beyond. The war in Ukraine has drained Russia’s military resources, but a frozen conflict or a negotiated settlement could allow Moscow to regroup and refocus its strategic ambitions.

Western policymakers often assume that Russia, weakened by its battlefield losses, will be deterred from further military aggression. This is a dangerously flawed assumption. Historically, Russia has demonstrated a capacity to absorb losses, reconstitute its forces, and shift its strategic priorities. Meanwhile, NATO’s ability to deter further Russian aggression remains in question. The alliance has expanded its troop presence in Eastern Europe, but its political cohesion and willingness to engage in direct military conflict remain uncertain—especially as some European states attempt to normalize relations with Moscow in pursuit of economic stability.

This article examines the possible vectors for NATO-Russia conflict if Ukraine achieves a peace settlement. It does not assume that war is inevitable, but it does take a cold, hard look at the geopolitical realities that could push the two sides toward renewed confrontation. The analysis focuses on six primary conflict scenarios:

Each of these potential flashpoints represents a different type of escalation risk. Some are conventional military threats, while others involve hybrid warfare, cyber operations, or economic coercion. Taken together, they illustrate why a Ukraine peace agreement does not mean NATO and Russia are on the path to long-term stability.

The Suwałki Gap, a narrow 65-kilometer corridor between Poland and Lithuania, is one of NATO’s most strategically vulnerable points. If a Ukraine peace agreement is reached, Russia could shift its military focus, and the Suwałki Gap would become an even more likely flashpoint. The corridor separates Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave from Belarus, Moscow’s closest military ally. If Russia were to seize the Gap in a rapid military operation, it could effectively cut off the Baltic states from NATO reinforcements, testing the alliance’s Article 5 commitments and forcing NATO into a difficult military dilemma. Given Russia’s past use of hybrid warfare, any confrontation here could begin with ambiguous tactics before escalating into a broader conventional conflict.

Geopolitical Importance: A Bottleneck for NATO

The Suwałki Gap has been a recognized weak point in NATO’s eastern defense posture for years. The significance of this narrow stretch of land lies in its geography—it serves as the only land connection between the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) and the rest of NATO.

Russia has two strategic goals in the region: securing Kaliningrad and isolating the Baltics. Kaliningrad, a heavily militarized Russian exclave sandwiched between NATO states, hosts advanced missile systems, including nuclear-capable Iskander missiles, S-400 air defense batteries, and electronic warfare units. Belarus, meanwhile, is increasingly integrated into Russian military structures, with joint exercises and a growing Russian troop presence. If Russia were to attempt a land grab to connect Kaliningrad with Belarus, NATO forces in the region would be under immediate threat.

For NATO, maintaining access to the Baltics is essential. If Russia controls the Suwałki Gap, it would create a logistical nightmare for NATO forces trying to reinforce its easternmost members. Air and sea routes would become the only viable supply options, which would be highly vulnerable to Russian anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems. This makes the Suwałki Gap not just a strategic weakness but a potential early battleground in any NATO-Russia confrontation.

Military Posturing and Force Readiness

Both NATO and Russia have been actively preparing for a possible conflict in this corridor. Since Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, NATO has increased its rotational forces in Poland and the Baltics. The Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP) battalions, deployed in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, were designed to deter Russian aggression. However, these multinational battlegroups, each consisting of around 1,000-1,500 troops, are primarily a tripwire force—they are not large enough to repel a full-scale Russian assault without immediate reinforcements.

Russia, on the other hand, has consistently built up its military presence in Kaliningrad and along the Polish-Belarusian border. The Zapad military exercises, which take place every four years, simulate large-scale conflicts with NATO and often include scenarios involving the rapid seizure of strategic points in Poland and the Baltic region. In 2021, Russia and Belarus conducted joint maneuvers that explicitly rehearsed closing the Suwałki Gap. The exercises involved tens of thousands of troops, airborne assaults, and simulated strikes on NATO logistics hubs.

If Ukraine reaches a peace agreement that freezes the conflict, Russia will likely shift its military focus toward rebuilding and modernizing its forces for potential conflicts elsewhere. Given the degradation of Russia’s conventional military due to the war, a direct confrontation with NATO remains unlikely in the short term. However, if Moscow believes NATO is overstretched or politically divided, it could take calculated risks, potentially using hybrid tactics to test NATO’s resolve in the region.

Potential Conflict Scenarios

While an outright invasion is unlikely in the near term, there are several ways in which a Suwałki Gap conflict could unfold:

NATO’s Countermeasures and Strategic Challenges

NATO has recognized the threat posed by the Suwałki Gap, but significant challenges remain in ensuring its defense:

Conclusion: A Dangerous Flashpoint

The Suwałki Gap remains one of NATO’s most exposed vulnerabilities, and any future NATO-Russia conflict could very well begin here. A peace agreement in Ukraine does not eliminate the risk of Russian aggression elsewhere. On the contrary, if Russia emerges from the war with its strategic goals unmet, it may look to assert its strength in other regions where NATO’s response is uncertain. While NATO has taken steps to strengthen its eastern flank, it must do more to ensure that the Suwałki Gap does not become the next battlefield in the ongoing struggle between Russia and the West.

The Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—represent one of the most precarious regions in NATO’s security architecture. Sandwiched between Russia and its heavily militarized exclave of Kaliningrad, these nations are acutely aware of their vulnerability. Their geographic position, combined with their small military forces, makes them potential targets for Russian aggression should Moscow seek to test NATO’s resolve after a Ukraine peace settlement.

A peace agreement in Ukraine will not erase Russia’s broader strategic objectives. On the contrary, if Moscow determines that NATO’s response to Russian aggression was weak or divided, it may feel emboldened to challenge the alliance elsewhere. The Baltic region, with its history of Russian influence, sizable Russian-speaking populations, and logistical constraints for NATO reinforcements, presents an ideal target for Kremlin hybrid or direct military pressure.

The Baltic states regained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 and have since become some of NATO’s most vocal members, advocating for stronger deterrence measures against Russia. Their history with Moscow is one of occupation, subjugation, and resistance. Estonia and Latvia, in particular, have significant Russian-speaking minorities—remnants of Soviet-era population transfers—who have been a focal point of Kremlin propaganda and influence operations.

Russia has used the claim of “protecting Russian speakers” as a pretext for intervention before, most notably in eastern Ukraine in 2014. The same rhetoric could be applied to the Baltics, particularly in Narva (Estonia) or Daugavpils (Latvia), both of which have large Russian-speaking populations. Moscow could manufacture grievances, claim discrimination against these communities, and use hybrid warfare tactics to destabilize the region.

Moreover, Latvia’s intelligence services have warned that Russia could rebuild its military forces within five years if the Ukraine war is frozen, creating a renewed threat to NATO’s eastern flank. This aligns with previous Russian strategic behavior—using periods of reduced conflict to consolidate power and prepare for future engagements.

Despite NATO’s Article 5 commitment to collective defense, there are legitimate concerns about whether the alliance would respond decisively to a limited Russian incursion in the Baltics. Unlike Ukraine, the Baltic states are NATO members, meaning an attack would legally require an allied military response. However, given NATO’s internal political divisions and reliance on consensus decision-making, a rapid response is not guaranteed.

NATO’s Military Presence in the Baltics

The main problem is that these reinforcements would take time. In the early stages of a conflict, Russia could use a combination of cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, and limited military actions to create confusion and slow NATO’s decision-making process. A rapid military strike—similar to Russia’s 2014 seizure of Crimea—could force NATO into an uncomfortable position where its response options are constrained by political hesitation and logistical difficulties.

Russia’s Military Posture

Several pathways could lead to a NATO-Russia confrontation in the Baltic region. While a full-scale invasion remains unlikely, Russia could test NATO in more subtle ways.

1. Hybrid Warfare and “Little Green Men”

Russia has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to wage hybrid warfare, combining cyberattacks, disinformation, and irregular forces to destabilize regions before a full military engagement. A future Baltic crisis could begin with:

These tactics could create a pretext for Russian intervention without immediately triggering Article 5, forcing NATO into a political crisis over how to respond.

2. A Limited Russian Military Incursion

If Moscow believes NATO’s commitment to the Baltics is weak, it could conduct a limited incursion—perhaps seizing a small border town or strategic area under the guise of protecting Russian-speaking populations. By presenting NATO with a fait accompli, Russia could challenge the alliance to either escalate the conflict or accept the territorial loss.

Such a scenario would mirror the 2014 annexation of Crimea, where Russia moved quickly before Western powers could organize an effective response. The key question would be whether NATO leaders, especially the United States, would be willing to commit to a full military response over a relatively small territorial dispute.

3. Miscalculation Leading to Escalation

Given the high concentration of military assets in the region, accidental clashes between NATO and Russian forces remain a serious risk. A miscalculation—such as a NATO fighter jet intercepting a Russian aircraft too aggressively or a naval incident in the Baltic Sea—could quickly spiral out of control. Russia has repeatedly tested NATO’s air defenses with near-daily incursions into Baltic airspace, increasing the risk of unintended escalation.

To deter Russian aggression in the Baltics, NATO has taken several steps, but challenges remain:

The Baltic states are not just NATO members; they are the alliance’s frontline against Russian aggression. Any conflict in this region would be a direct challenge to NATO’s credibility and could rapidly escalate into a full-scale war. While a Ukraine peace agreement may momentarily shift Moscow’s focus, it does not eliminate the risk of confrontation. Russia has long viewed the Baltics as part of its historical sphere of influence, and if it sees an opportunity to test NATO’s resolve, it may do so through hybrid tactics, limited incursions, or even direct military aggression.

If NATO is serious about deterrence, it must ensure that its presence in the Baltics is more than symbolic. The next conflict may not begin with tanks rolling across the border—it could start with a cyberattack, a manufactured political crisis, or a calculated Russian gamble. In any case, the stakes remain dangerously high.

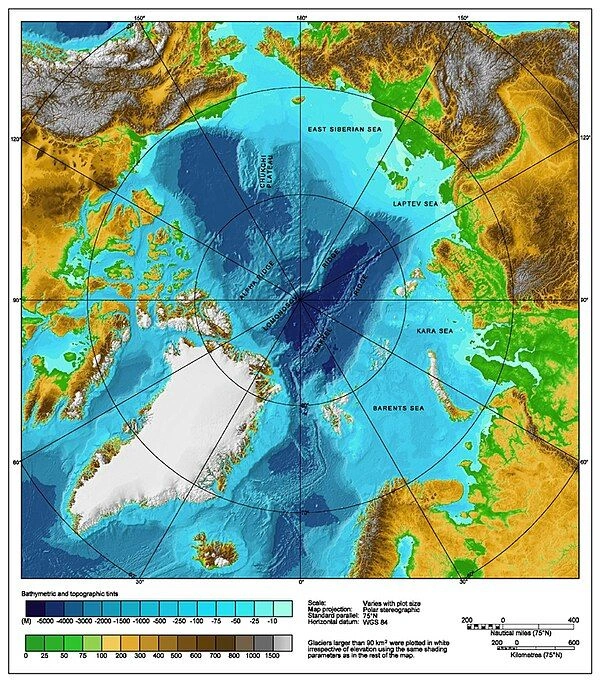

As the Arctic ice continues to melt, a new geopolitical battleground is emerging between NATO and Russia. This is not a conventional battlefield of tanks and troops, but rather a contest over resources, military positioning, and control of strategic maritime routes. Russia has long regarded the Arctic as its strategic backyard, and its militarization of the region has been accelerating over the past decade.

If the Ukraine war reaches a peace agreement, Moscow may shift its focus northward, seeking to consolidate its dominance in the Arctic while NATO is preoccupied elsewhere. The region’s vast untapped oil and gas reserves, new shipping lanes, and growing military presence make it a potential vector for future NATO-Russia conflict.

Russia has been steadily expanding its military footprint in the Arctic, positioning the region as a key element of its national defense strategy. The Russian government has designated the Arctic as a “strategic priority”, investing heavily in infrastructure, military bases, and advanced weapons systems.

The Kremlin justifies this buildup as a defensive necessity, but NATO officials increasingly view Russia’s Arctic expansion as a power projection effort, aimed at securing dominance over the region’s resources and waterways.

The Arctic is home to an estimated 30% of the world’s undiscovered natural gas and 13% of its undiscovered oil reserves. As global energy markets shift and Russia faces Western sanctions, these resources are critical for Moscow’s economic survival.

At the same time, the opening of new Arctic shipping routes—particularly the Northern Sea Route (NSR)—is transforming global trade. The NSR dramatically reduces shipping times between Europe and Asia, cutting travel distances by up to 40% compared to the Suez Canal route.

As tensions rise, accidental or deliberate confrontations between Russian and NATO forces in the Arctic are becoming more likely.

There are several ways NATO and Russia could clash in the Arctic, ranging from economic disputes to military confrontations.

1. Maritime Confrontation Over Arctic Shipping Lanes

One of the most immediate conflict vectors is freedom of navigation. Russia insists that foreign military vessels must seek permission to transit the Northern Sea Route, a position that directly contradicts international maritime law.

If NATO warships attempt to transit the NSR without Russian approval, Moscow could respond with military force—potentially using naval blockades, forced boardings, or missile threats. This could escalate into naval skirmishes, particularly as Russia expands its Arctic naval patrols.

2. Resource Conflicts and Economic Warfare

Russia has begun unilaterally claiming Arctic energy resources, granting exploration rights to Russian companies in contested waters. If Western energy firms attempt to drill in disputed Arctic territories, Russia could use coercive economic tactics—such as sanctioning Arctic investments or deploying paramilitary “fishing fleets” to disrupt Western operations.

This scenario mirrors China’s gray-zone tactics in the South China Sea, where state-backed fishing fleets are used to assert control over maritime zones. NATO Arctic states—particularly Norway and Canada—are concerned that Russia will adopt similar strategies in the Arctic.

3. Military Escalation Over Arctic Airspace and Submarines

The Arctic is a critical zone for strategic bombers and nuclear submarines, both of which are essential for Russia’s nuclear deterrence strategy.

While NATO recognizes the Arctic as a critical front, the alliance faces several key challenges in countering Russian dominance.

The Arctic is no longer just an isolated expanse of ice—it is rapidly becoming a geopolitical flashpoint where NATO and Russia are in direct competition. A Ukraine peace agreement will not reduce these tensions; instead, it may allow Russia to divert military resources northward, solidifying its Arctic dominance while NATO remains preoccupied elsewhere.

If NATO fails to assert its presence in the Arctic, Russia will likely push the boundaries further—restricting access to Arctic shipping routes, seizing control over disputed resources, and militarizing the region even more aggressively. Whether through maritime confrontations, resource disputes, or military escalations, the Arctic is poised to become a major vector for future NATO-Russia conflict.

While conventional military conflict between NATO and Russia remains a high-risk scenario, cyber warfare and hybrid threats present a more immediate and likely vector for escalation. Russia has long relied on asymmetric tactics to weaken Western adversaries, using cyber operations, disinformation campaigns, and political subversion instead of direct military confrontation. These methods allow Moscow to exert influence and create instability while maintaining plausible deniability.

A peace agreement in Ukraine would not signal the end of Russian hostilities; rather, it would shift the battleground to less conventional arenas where NATO’s ability to respond is more constrained. Cyber warfare provides Russia with a low-cost, high-impact means to disrupt NATO operations, undermine Western economies, and weaken political cohesion within the alliance.

Russia’s cyber warfare strategy is deeply integrated into its broader military doctrine, often described as “non-linear warfare” or the Gerasimov Doctrine. This approach blends military, political, economic, and informational warfare into a single, continuous campaign against adversaries.

Key Components of Russian Cyber Warfare

By weaponizing the digital sphere, Russia can keep NATO off-balance, undermining its ability to organize a unified response to Russian aggression.

Hybrid warfare goes beyond just cyberattacks—it includes political subversion, economic coercion, disinformation, and proxy warfare. Russia has successfully used hybrid tactics in multiple conflicts, including Ukraine (2014), Syria (2015), and even NATO states like Estonia (2007).

1. Disinformation and Psychological Operations (PsyOps)

2. Proxy Conflicts and Unconventional Warfare

3. Economic Warfare and Energy Manipulation

Hybrid threats are designed to create instability without triggering NATO’s collective defense response under Article 5. By staying below the threshold of conventional war, Russia can continuously undermine NATO’s strategic cohesion.

Several pathways could lead to serious escalation in the cyber domain, with potential spillover into conventional warfare.

1. Large-Scale Cyber Attack on a NATO Country

If Russia crippled the power grid of a NATO member, it could be seen as an act of war. The 2017 NotPetya cyberattack, which originated from Russia and caused $10 billion in global damage, is an example of what a massive cyber offensive could look like.

2. Cyber Attack on NATO’s Military Command and Control (C2) Systems

3. NATO’s Counter Cyber Offensive: Tit-for-Tat Escalation

Despite increasing investment in cyber defense, NATO faces several weaknesses:

Unlike conventional battlefields, cyber warfare and hybrid threats are already ongoing, with Russia continuously probing NATO’s defenses. A Ukraine peace agreement would not end these hostilities—it would intensify them as Russia redirects its efforts toward undermining NATO through digital and hybrid warfare.

Cyber attacks, disinformation campaigns, and political subversion allow Russia to weaken NATO without direct military confrontation. If NATO fails to fortify its cyber resilience and hybrid warfare response, Moscow will continue exploiting this shadow battlefield to shift the balance of power in its favor.

While the Balkans may not appear to be the most obvious vector for a NATO-Russia conflict, the region remains one of Europe’s most volatile geopolitical flashpoints. The Balkans have a long history of ethnic tensions, unresolved disputes, and external meddling by great powers. Russia has consistently used political influence, economic leverage, and intelligence operations to maintain its foothold in the region, particularly through its strong ties with Serbia. NATO, for its part, has expanded its influence by integrating former Yugoslav states into the alliance, a move that Moscow views as blatant Western encroachment.

With Ukraine potentially reaching a peace agreement, Russia could redirect its focus to destabilizing the Balkans, using it as a pressure point to challenge NATO without direct military confrontation. The region provides Moscow with an opportunity to create chaos without directly violating NATO’s red lines, forcing the alliance to divert resources and attention away from other theaters.

Russia’s influence in the Balkans primarily revolves around Serbia, a historical ally with deep cultural, religious, and military ties to Moscow. The Kremlin has positioned itself as a defender of Serbian interests, particularly regarding Kosovo, which Serbia refuses to recognize as an independent state.

Russia’s goal in the Balkans is not outright military conquest, but rather political and economic destabilization. By supporting nationalist movements, Moscow can fuel internal conflicts, disrupt NATO expansion, and weaken Western influence in the region.

NATO has expanded significantly in the Balkans, integrating Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia into the alliance. However, this expansion has not eliminated security risks.

Several pathways could lead to NATO-Russia confrontation in the Balkans, ranging from covert destabilization to open military escalation.

1. Serbia-Kosovo Conflict Triggered by Russian Influence

2. Republika Srpska Moves Toward Secession

3. NATO Confrontation with Russian Hybrid Forces

To counter Russian destabilization efforts in the Balkans, NATO must take proactive measures:

While NATO has been preoccupied with Ukraine and the Eastern European front, the Balkans remain a high-risk theater for renewed conflict. Russia sees the region as a low-cost, high-reward opportunity to undermine NATO without direct military confrontation.

If NATO does not take decisive steps to counter Russian influence, Moscow could engineer a crisis in the Balkans, drawing NATO into a dangerous political and military quagmire. With historical grievances still raw and nationalist movements on the rise, the Balkans remain one of Europe’s most dangerous unresolved conflicts—and one that could easily be weaponized in a NATO-Russia showdown.

The Black Sea has been a battleground for influence between Russia and NATO for decades. Russia sees the Black Sea as a core strategic asset, essential for projecting power into the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and North Africa. NATO, on the other hand, has worked to counterbalance Russian dominance in the region, supporting allies such as Turkey, Romania, and Bulgaria while deepening partnerships with Ukraine and Georgia.

A Ukraine peace agreement would not reduce tensions in the Black Sea—it could escalate them. With its land war winding down, Russia would be free to refocus on naval and hybrid threats, strengthening its grip over the region while challenging NATO’s influence. If the alliance fails to respond effectively, Russia could solidify its control over one of Europe’s most important maritime corridors, permanently reshaping the balance of power.

Russia’s military doctrine views the Black Sea as a launchpad for power projection, and Moscow has taken extensive steps to reinforce its position:

By securing naval superiority in the Black Sea, Russia ensures it cannot be easily contained by NATO forces, giving it a geopolitical advantage.

NATO has attempted to counterbalance Russian influence in the Black Sea, but the alliance faces several structural and geopolitical challenges:

Without a stronger naval posture, NATO risks ceding control of the Black Sea to Russia.

Several key events could escalate tensions between NATO and Russia in the Black Sea, even in the absence of direct warfare.

1. Naval Confrontation Between NATO and Russian Forces

2. Russia Expands Its Maritime Blockade Tactics

3. Increased Russian Missile Threats Against NATO Coastal States

To prevent Russian dominance in the Black Sea, NATO must adopt a more assertive regional strategy:

The Black Sea remains a strategic hotspot, where NATO and Russia are already in direct competition. A Ukraine peace deal would not reduce tensions—it would allow Russia to focus more resources on naval supremacy, making the region even more contested.

Unless NATO reinforces its presence, improves regional defenses, and counteracts Russia’s hybrid tactics, Moscow could effectively turn the Black Sea into a Russian-controlled maritime zone, restricting NATO’s influence and projecting power deeper into Europe and the Middle East.

A direct NATO-Russia naval clash may seem unlikely, but history has shown that naval conflicts often start over miscalculations. The question is not if the Black Sea will remain a flashpoint—but whether NATO is prepared for the inevitable showdown.

A Ukraine peace agreement, should it be reached, will not mark the end of tensions between NATO and Russia. Rather, it will shift the battleground to other, more vulnerable theaters where Moscow can exploit NATO’s weaknesses. Russia has demonstrated a long-term strategic patience, using periods of relative calm to rebuild its military, refine its tactics, and prepare for the next phase of confrontation.

The vectors for future NATO-Russia conflict are numerous and deeply embedded in existing geopolitical fault lines:

NATO cannot afford complacency. If the alliance fails to address these emerging threats with robust deterrence, military preparedness, and strategic cohesion, Russia will continue to push the boundaries of what it can get away with.

The question is no longer whether NATO and Russia will clash again—it is where, how, and whether NATO will be ready when it happens. The other question is whether a direct NATO-Russia conflict will inevitably bring about WWIII.

[…] Strategic Message: Signals Russia’s advanced missile tech and willingness to escalate; tests NATO and Ukraine’s defensive readiness as Donald Trump threatens to withdraw the United States from NATO. […]

[…] NATO & European Security Interests – The broader Atlantic security environment, including Russia’s recent submarine activity, may also provide an alternative explanation for the timing of the visit as there are currently multiple flashpoints for a European war between NATO and Russia. […]